We know the script by now. It’s the late 70s. Progressive rock has had its day in the sun, and now its bloated carcass lies dying in the street, kicked into the gutter by the nascent fury of thousands of punk rockers. In a few short years it has risen majestically, daring to challenge perceived convention, ripped up the rule book and owned arenas around the world. But it has become the victim of its own success; a cumbersome beast in thrall to its own peccadilloes. And then along came punk rock…

Except no one thought to tell Marillion.

In truth, punk rock was already almost an afterthought when a young Buckinghamshire drummer by the name of Mick Pointer, with a head full of rock-star dreams, was looking for a band to join. If you believed the media, the music that inspired him – such as Camel, Deep Purple, Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin, Genesis – was also an afterthought.

“I thought there’s got to be other people that are into this style of stuff,” Pointer recalls today. “Honestly, it was simplistic, but that’s actually what I thought. And I thought: ‘Not everybody has got a fucking spiky haircut now.’”

But soon Pointer found some like-minded musicians without spiky haircuts, and joined Electric Gypsy, who also included future Solstice guitarist Andy Glass and a bassist by the name of Doug Irvine.

“It was a 60s/70s mid-rock sort of thing,” Pointer remembers. “There wasn’t any particular route anybody was going down. I don’t think we had any particularly big ambitions to make too much of it. We were pretty young – just get in a room and start playing. It was pretty ad-hoc, to be honest with you.”

Lurking beneath the surface, however, was a determination that would become a staple for where things would move next. Frustrated by a lack of ambition in the band, Pointer and Irvine decided to move on.

“I got along particularly well with Doug,” Pointer says. “As usual with most of these things, everything was done down at the pub. We spent all the time together just mapping out where we’d like to go, like everybody does when they’re young. So me and him said let’s form our own band, and put our own guys together that would suit what we’re attempting and trying to do.”

And in one fell swoop, Marillion were born. Except they weren’t called Marillion back then. Inspired by a Tolkien book that Irvine had, the new outfit called themselves Silmarillion. The early line-up was Irvine (bass) and Pointer (drums), keyboard player Neil Cockle and guitarist Martin Jenner. Camel, with whom Irvine and Pointer shared a mutual love, became their main reference point.

“We used to rehearse in the Princes Risborough area,” Pointer recalls. “We had this rehearsal room, and in the other room happened to be…”

You guessed it…

“…Camel! They would come in and watch us. Very fleetingly, but it was a bit of a moment for us. We wrote all our own material. Me and Doug had a lot of our own material we were working on and it was all instrumental.”

This line-up only played one gig, at Southall’s Hanborough Tavern, at the tail-end of 1978. The band then split following a row over equipment, leaving a core of Pointer and Irvine.

“Doug said, okay, let’s find two other people we need. We put an advert in [weekly paper] Musicians Only.”

First to answer the call was a young guitarist from Whitby called Steve Rothery. Legend suggests he arrived unannounced with guitar in hand, although in truth today no one can really remember.

“I came down and auditioned in the late spring of ’79,” Rothery does remember. “A band called Silmarillion, who had only ever done one gig, and it was really just a bass player with a drummer. I came down and got chosen for the guitarist. I gave up my job and moved down and lived in this little tiny cottage.”

Rothery had set his heart on playing guitar in a band, but when his own local band had all set off for college he set his sights further afield.

“I’ve got a funny feeling that he practically moved in from that day,” Pointer laughs. “I was practically living there myself as well. Then we were

still Silmarillion.”

Local keyboard player Brian Jelliman completed up the Silmarillion line-up, but before the band had even played their first gig (which would be at Berkhamsted Civic Centre, attended by a very fresh-faced Steven Wilson) there was one major change.

“During that time I suggested to Doug that while people left, we should lob off letters of the name – jokingly, down at the pub,” Pointer laughs. “But ‘Ilmarillion’ didn’t sort of work. So we got rid of the S, I, and L. That’s how we ended up with Marillion.”

At this stage the band’s repertoire was slowly taking shape. Certain sections of early material like Herne The Hunter, The Haunting Of Gill House and Alice would later be adapted into some of Marillion’s better-known early songs. The band recorded two demos in March and the summer of 1980. The first featured the aforementioned songs alongside Scott’s Porridge, the second featured another version of Alice, along with Lady Fantasy and Close, parts of which would later resurface in He Knows You Know, The Web and Chelsea Monday.

“There’s a bunch of stories about why that came about,” Fish will chuckle later on. “I heard that when they were called Silmarillion they were too lazy to change the stencil. They just blacked out the ‘Sil’.”

And so, in 1979, 40 years ago, Marillion were born. Although less than a year in there would be yet another line-up change.

“Doug left when he reached the ripe old age of 25,” says Rothery. “He decided he hadn’t made it. He was going to knock it on the head. It was probably less than a year. We had done maybe about five shows, just weird and wonderful things: we played at a hospital; we played a street carnival on the back of a trailer in Watford, supporting Garston Magicians. So we weren’t setting the world on fire. We did a gig at a High Wycombe student bar. That was probably one of the better ones we did. It was my dream, and we probably weren’t thinking too far ahead.”

“There were parts of that original Silmarillion set that actually found their way on to [debut album] Script For A Jester’s Tear,” says Pointer. “Some of the Grendel stuff certainly was kicking around at that point. And certainly some of The Web was kicking around that, certain parts of Garden Party. When we became Marillion, Doug took over the vocal parts. He was starting to add lyrics.”

Still, without their bass player and sometime vocalist, the band needed to kick on if they were to maintain their momentum. It was back to Musician’s Only and another add. Although this was only for a new vocalist/bass player.

“Because we were quite entrenched in the Camel sort of way, I couldn’t see us with a frontman,” admits Pointer.

Fate, however, was to see things differently. Former student and forestry worker Derek William Dick, the man who would be known as Fish, was another young man with rock-star dreams.

“I was two years into a three-year course for forestry,” he says, “andI jacked it and decided to be a singer.”

His early forays into music had seen Fish ply his youthful trade with Stoned Dome Band, where he’d met bass player William ‘Diz’ Minnitt. The pair had struck up a friendship which had seen them relocate to Cambridge, where Fish’s then-girlfriend was studying, when the rest of Stoned Dome Band’s lack of ambition became apparent. When money ran out they returned to the Scottish borders, intent on starting a new band. While there they saw an ad from a band in Aylesbury looking for a singer/bassist in Musician’s Only.

“We wrote to them saying we were a singer and bassist,” says Fish. “They wrote back and sent a tape up. It was largely instrumental, very few lyrics. So we did stereo recordings and put on one track on the stereo recorder, and I sang on the other. I did some Genesis songs, some Yes songs. Basically copied other people’s vocals.”

“I remember the tape turning up,” recalls Pointer. “Back then you could use a cassette tape, and put a piece of music on one track of the stereo, and then on the other he would be singing along. One of the ones that stood out

to me was the Genesis stuff he was singing along to.”

“My last 10 pence went in a phone box in Ettrickbridge, which was the phone call I made,” Fish laughs. “It was like, okay, we’re going for it. And we basically loaded everything up in the blue combi van and Diz drove down to Aylesbury. We were going there and fuck it; we’re loading everything up and putting everything in that basket. They met us in a pub and we got on okay, and it started to move on from there.”

“He and Diz basically said, ‘Yeah, okay, let’s go for it’,” says Pointer. “So that was the nucleus, I suppose, of the Marillion that most people initially are aware of.”

The new five-piece line-up of Marillion wasted no time in getting down to business, and kicked off an intense 10-week rehearsal at Leyland Farm Studios in Buckinghamshire before playing their debut gig, at Bicester’s Red Lion Pub on March 14, 1981, in front of an audience of 65. In July, with four months of serious gigging under their belt, they entered Roxon Studios in Oxfordshire, with local musician Les Payne producing, where they recorded a new demo featuring the more recognisably titled He Knows You Know, Garden Party and Charting The Single, which they’d sell at gigs for the princely sum of £1.25.

Yet despite making considerable headway throughout most of 1981, towards the end of the year change was afoot.

“The thing was that Steve had come down from Yorkshire and joined the band,” Fish explains. “I’d come down from Scotland. So our dedication levels were a little bit higher. It was like, don’t fuck about. For me, I was going to make this fucking work.”

“I was very ambitious,” adds Pointer. “My ambition was also matched by Derek’s ambition as well. Me and him would plot and plan as much as we possibly could. You’ve got to keep pushing and moving forward.”

It was keyboard player Brian Jelliman who was the focus of the discontent.

“I think there was a personality clash with him and Derek,” Pointer muses. “And also the route we were taking was going a little bit further away from where he was at.”

“Brian didn’t seem committed,” Fish concurs. “I didn’t think he was a particularly good keyboard player.”

The situation was heightened when Marillion were supported by a young Essex prog band called Chemical Alice. Both Fish and Pointer were impressed by their keyboard player, Mark Kelly.

Mick Pointer: “There was this guy in this band who was basically throwing his keyboards around. At that point, it seemed really exciting, because Brian was really static.”

Fish: “I remember Mick Pointer and I were standing at the bar. It was kind of like: ‘That’s a great keyboard player.’ Then we made the approach.”

Mark Kelly remembers being approached by the tall Scotsman and the Marillion drummer. But at that point he had only seen them play a few songs, so the following week he made his way across London to see Marillion play Chesham’s Elgiva Hall in November 1981.

“Brian spotted me and recognised me from the previous week,” he reveals. “He asked Fish: ‘What’s he doing here?’ I went back to Fish’s house, and the next morning they went round and told Brian that he was fired – after I said that I would join.”

Replacing Brian Jelliman with Mark Kelly could be seen as ruthless subterfuge; or the product of the strength of determination to succeed that existed within many of the band members. Either way, the band were building up a serious head of steam, even if they remained below the radar of the mainstream media. Although that was probably a good thing for a band steadfastly creating progressive rock at a time when new wave was beginning to morph into New Romantic as the media’s then-darlings.

As Marillion’s line-up transmogrified into the one most fans readily associate

with the early years, so the band were fine-tuning other areas of their organisation, which helped set them apart from their peers. The first issue of The Web, the band’s newsletter (an early inspiration for this writer) appeared in February 1982, pulling their fan base into an increasingly tight network. They were already a hard-working road band, and their own music was developing apace, even if every record label who’d been sent the Roxon demo had passed on them.

“You didn’t care to conform to the normal structure,” offers Rothery today, of the band’s developing sound, which was deeply rooted in the progressive rock favoured by all five band members. “All the music you loved didn’t do that anyway. So you’d just have that freedom. What comes across when I listen to the early stuff, it’s very unselfconscious. It’s very natural for young musicians who’d grown up listening to a certain kind of music to then want to do that – to emulate their heroes and take that ethos or that approach. I think that definitely shines through, especially with the early stuff.”

“If you wanted to put the big Venn diagram together,” Fish adds, of those heroes the band were happy to emulate, “you had Pointer who was into Rush, that was his main thing. He wanted to be Neal Peart. And he was into Yes, Genesis. Then you had Mark Kelly, who was more a Yes-type person. But again, he liked Genesis. And Steve was more Camel, but liked Hackett and Genesis. So when you put the Venn diagram together, the one influence who was there between all the members of the band was Genesis. That was where it fell.”

It was on the road that the music was given the space to breathe. Their first show with new keyboard player Mark Kelly was at the Great Northern in Cambridge on December 1, 1981. It included five of the six songs that would appear on the band’s debut album, plus Charting The Single, the epic Grendel and the carousing live favourite Margaret, named after the band’s trusty touring van.

“From when I joined, at the end of ’81, early ’82, the band really went from being a pub band to regular sell-out shows at the Marquee,” adds Kelly. “And then we did the Reading Festival in 1982. We weren’t very high up on the bill, but we were on the festival.”

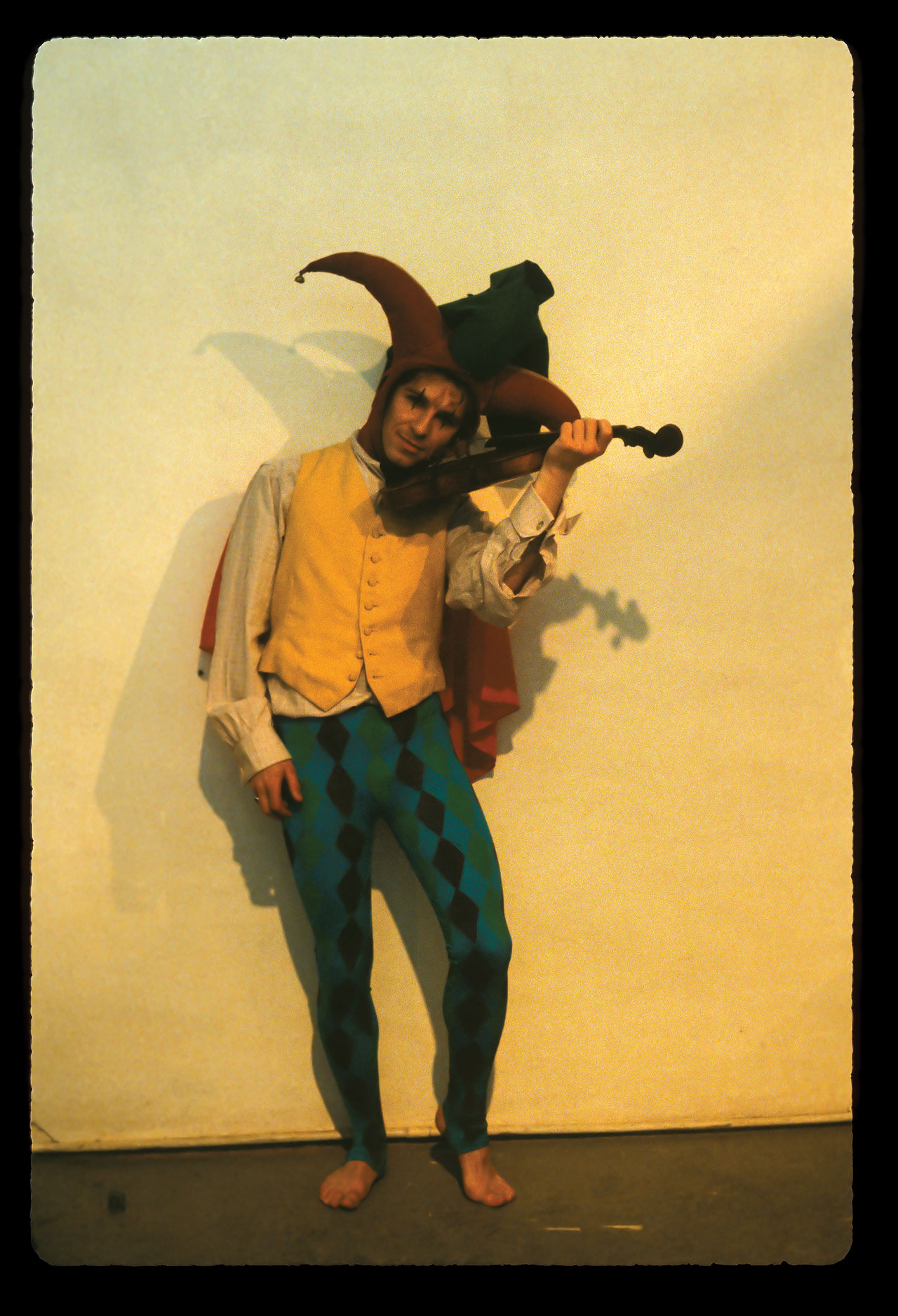

It wasn’t just the music and the road work. With such an imposing frontman as Fish, Marillion were slowly carving out a reputation as a band you needed to take notice of. At almost six-feet-five he struck a dominant figure, whose choice of face paint, initially to mask his own on-stage insecurities, helped make Marillion stand out yet further, and the band opted for stage effects and early costumes to strengthen their identity.

“You had a six-foot-five singer, and I painted my face because I was shy,” explains Fish. “It was a mask that I put on that enabled me to go in front of an audience. And then it became a calling card. I ended up using Leichner. Before I’d discovered the Leichner grease paints – which I got from a kids’ party joke shop thing in Aylesbury Market in Friars Square – I used all sorts of shit. Including nail varnish!

“We’d gone Hammer Horror too! Hammer Films at the time had a big sale. We went up to the auction and bought all the crosses and stuff and wreaths and shit like that. We were going into pubs and people remembered us. I would know the whole set. On the night of the performance, we wanted to get as many people to like Marillion. We had The Web newsletter. It was all organised by Steph Jeffrey, Mick’s partner. She was the fan club secretary. There was definitely a plan.”

“I remember one of my first gigs with the band,” Rothery chuckles. “Privet [Christopher Hedge], who became our sound engineer, was doing pyrotechnics for us at that time. And one of the flash bombs didn’t go off, so he had the great idea of scraping it into another pot and setting off two simultaneously. So this sheet of flame goes up my back. It could have been a very short career.”

An even bigger step was when the band finally got the nod from the BBC to record a session for The Friday Rock Show, which at the time was about the only outlet for rock music on national radio and television. It was recorded with producer Tony Wilson at the BBC’s Maida Vale Studios on January 29, 1982.”

“The Friday Rock Show session was a real boost for us,” states Kelly. “I think that came about because we had opened for a band called Spider. Spider’s manager was a woman called Maggi Farran, and she was married to Tony Wilson, who was there at that gig and invited us to come and do some songs. That must have tripled or quadrupled our audience. Suddenly we went from being some home-county area band to having an audience all over the country.”

With everything very much in the ascendency, there was still one final line-up change that would take place before the Marillion of the band’s debut album was fully realised. This time the spotlight fell on Fish’s pal, bassist Diz Minnitt.

“That wasn’t my choice,” Fish protests today. “That was provoked by the rest of the band. They were saying that Diz wasn’t good enough. I was never quite sure whether it was because he was my mate or because he was a bass player. Diz was a good bass player, but he wasn’t as good as Pete [Trewavas, who replaced him].”

Mark Kelly takes up the story. “I had been in the band for a few months, and I realised that Diz wasn’t really up to the job. I suggested that maybe we might think about getting a new bass player. Which I thought, looking back, was a bit forward of me, because I’d only been in the band for a couple of months. But Fish agreed.”

Of all the musicians in the early days of Marillion, Pete Trewavas had perhaps achieved the most. He’d learned to play guitar with longtime friend Robin Boult at the age of seven, and was already a veteran of several local Aylesbury bands including the proggy Orthi and the more new wave The Metros, with whom he’d toured America. It was with The Metros that Fish had first stumbled across the young bass player. “I was kicking about in Aylesbury in the pubs and Pete was playing in The Metros,” he says. “I saw them and said, ‘This guy is fucking brilliant.’ I said, ‘I found a bass player.’

“Pete came up and auditioned in the garage of the house. I remember that because his bass was in a case that was covered in newspapers, because the case was falling apart, so he glued newspapers on it. And he left the fucking case in the back alley. It looked like something to be taken by the dustman. But he was in. He just clicked right away. And then we had to get rid of Diz. In that traditional Marillion way, it was like, ‘Who’s got to do it?’ ‘Well, Fish here can do it.’ So I had to fire my best mate before a gig.”

Mark Kelly remembers things slightly differently.

“Fish insisted on telling Diz before the gig that he was fired. And I thought that was crazy. He said, ‘Well, you tell him’, because it was my idea to get rid of him. Fish suggested I had to do it before the gig. And I’m like, ‘Do you think that’s a good idea? Why don’t we let him know after the gig?’ And he goes, ‘No, you’ve got to do it.’

So Fish stood there while he watched me saying to Diz that he was fired. And halfway through me trying to say, ‘Sorry, Diz…’ Fish was like, ‘You’re fucking it up, let me do it.’ And he just came in and told Diz that he was fired and that he was rubbish, or something like that. And of course Diz, quite understandably, went, ‘Well, I’m not playing the gig’ and he left.”

Marillion played that gig, at Milton Keynes The Starting Gate, on March 26, 1982, as a four-piece, before Pete Trewavas was drafted in for the next show, at Coventry’s General Wolfe Club on April 4.

“It was strange going on tour with a bunch of people you didn’t know actually. That was a weird experience.” says Trewavas. “It took a while to get to know anybody, really. I think I probably got to know Mark and Steve Rothery first. They were probably the easiest two people for me to get to know because we had kind of musical reference points and things in common we could talk about, I guess. I wasn’t sure about Fish. Because Fish was the dynamic frontman, and probably the leader of the group at the time, really. And you know what it’s like in bands. There’s all sorts of characters that make up a band. But it was interesting that there was a bit of a buzz and it seemed to be getting bigger.”

It was not only the buzz surrounding the Friday Rock Show sessions that were attracting attention for Marillion. At Fish’s behest, they’d taken the unusual step of employing a press officer to help their cause with the weekly UK music press, of which Sounds, the most rock-friendly, was already showing an interest. And not just any PR, but the legendary Keith Goodwin, who’d previously worked with the likes of Yes, Horslips and Argent.

“I had to learn very, very fast,” muses Fish. “I had a little paperback book that I bought. It was how to become a pop star. It had the basics – you need an agent, you need this. It was all real basic stuff. You need to get a press officer. And I decided that we had to get a press officer to get us noticed. I was introduced to Keith Goodwin. He had a little office on Oxford Street. I went down to meet him in June of 1981 or something. I remember it was a very, very hot day in London. I went down and played the demo, and he loved it.”

It helped, of course, that Marillion weren’t the only young band bringing a progressive rock sound back into vogue. Although today the band veer away from admitting there was a scene of sorts.

“We were doing something really different,” Fish snorts. “The press had allegedly buried progressive rock. We’d come up underneath the fucking radar into the Marquee club. Suddenly prog was back. Of course, Sounds would run the new progressive rock revival, the new wave of British prog and shit like that; it was like your Solstice and IQ and all that stuff. We were straight ahead of those bands.

“The only band that we’d played with that I can remember was Pallas. We were playing up in Scotland, and as far as we knew they were big up in Scotland. So we did a joint headliner with them. We basically went and played with them to get to their audience. But we weren’t phoning each other up asking what to do next. As far as that was concerned, we were Marillion and that’s us. We’re not part of any fucking movement, you know? We didn’t want anything to do with anybody else.”

By mid-1982, the momentum was definitely with Marillion. The likes of Pendragon, Twelfth Night and IQ might have all joined Marillion as being able to headline the Marquee, but Marillion were Marquee regulars. From a first headline show on January 25, they’d racked up a further 13 headline appearances at the celebrated London venue by the end of 1982.

“We were rolling big fucking dice,” Fish states proudly. “Trying to find angles and ways in. All the contacts for all the record companies came through Keith Goodwin or came through hunting people down. Without the internet. It was all phones. It wasn’t even mobiles. It was all coins and phone boxes and stuff. We were driven.”

Having been rejected by all and sundry a year previously, now the record labels were paying attention.

“You know, we almost signed with BBC Records,” says Pointer. “They actually had a record department. I know Charisma were interested in us as well.”

“Charisma sent this guy to basically do the deal,” adds Kelly. “And I don’t think he got the memo, because he basically offered us a two-singles deal. We just said we weren’t interested. Then EMI were hot on their heels. And then [manager] John Arnison said, ‘We’ve got you, basically, a five-album deal.’ We said that’s more like it.

“I know Tony Stratton-Smith [who looked after Genesis] at Charisma was really upset, because he really wanted to sign the band. And then he said to John, ‘Well, how about publishing? Can I sign the band for publishing?’ And actually we ended up signing for publishing through them. He was a good guy.”

“It’s funny,” laughs Trewavas, “because they’d say, ‘Oh, you walk in and we get a record deal.’ And I’d say, ‘No, no, no. I walk in and I get you a record deal!’ There was a bit of that banter going on. Because, of course, I hadn’t really done the hard work, they’d done the hard work.”

And so as the summer of 1982 drew to a close, Marillion, an unashamedly

progressive rock band, the like of which the music press had claimed were no more, had a major-label deal with EMI Records.

They recorded two sets of demos for EMI in July and September, the latter seeing them hooked up with, ironically, former Genesis producer David Hitchcock. It was also Hitchcock with whom they would record their debut single, Market Square Heroes, at Park Gate Studios in Battle, East Sussex that September. Which is somewhat ironic, seeing as it had been decided that the B-side of the 12-inch version would be the 17-minute epic Grendel – a song many had quickly pointed out bore a striking resemblance to Genesis’ 1972 epic Supper’s Ready, from the album Foxtrot, produced by… you guessed it, David Hitchcock.

“Not that I remember,” Pointer replies today when asked if Hitchcock himself picked up on the similarity between the two songs. “I think he was pretty happy to be working on another job. I think he had an extremely good career. But, like a lot of people, they’d be tarred with the progressive stuff, and then the punky stuff comes along and they don’t seem to get used.”

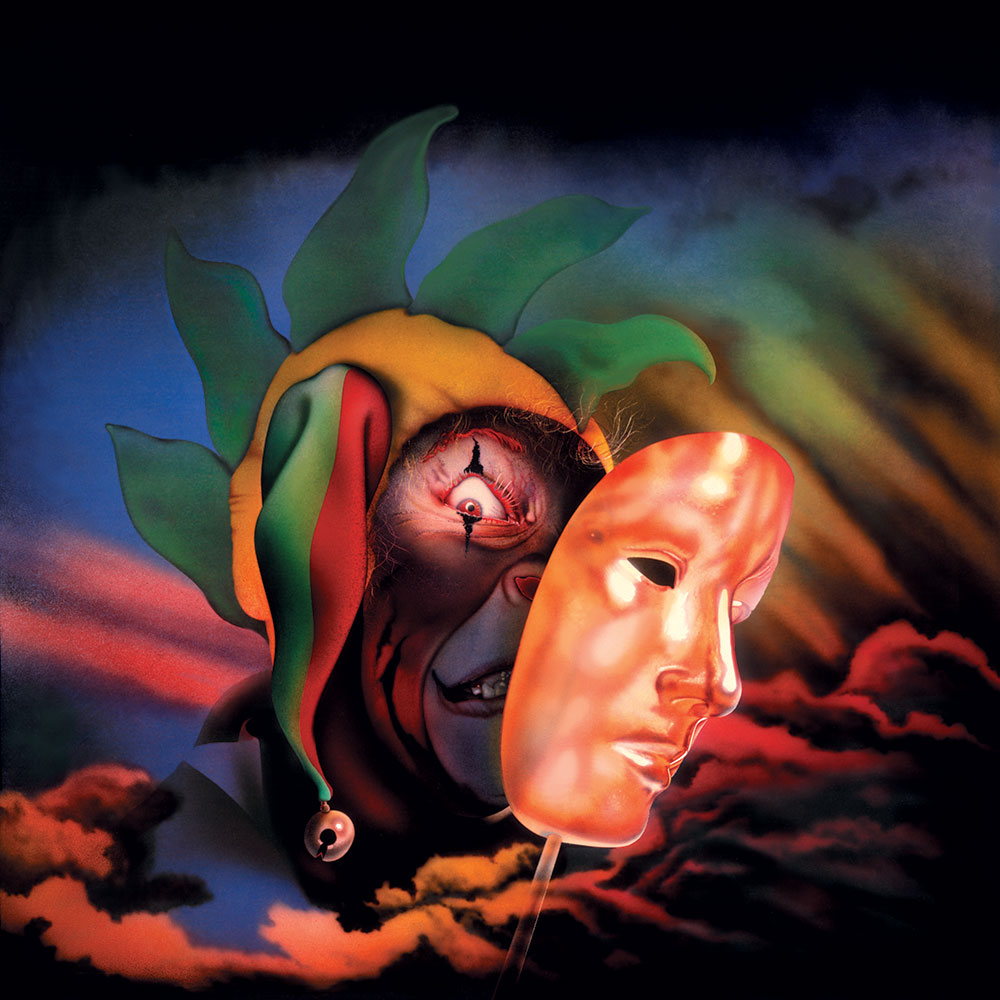

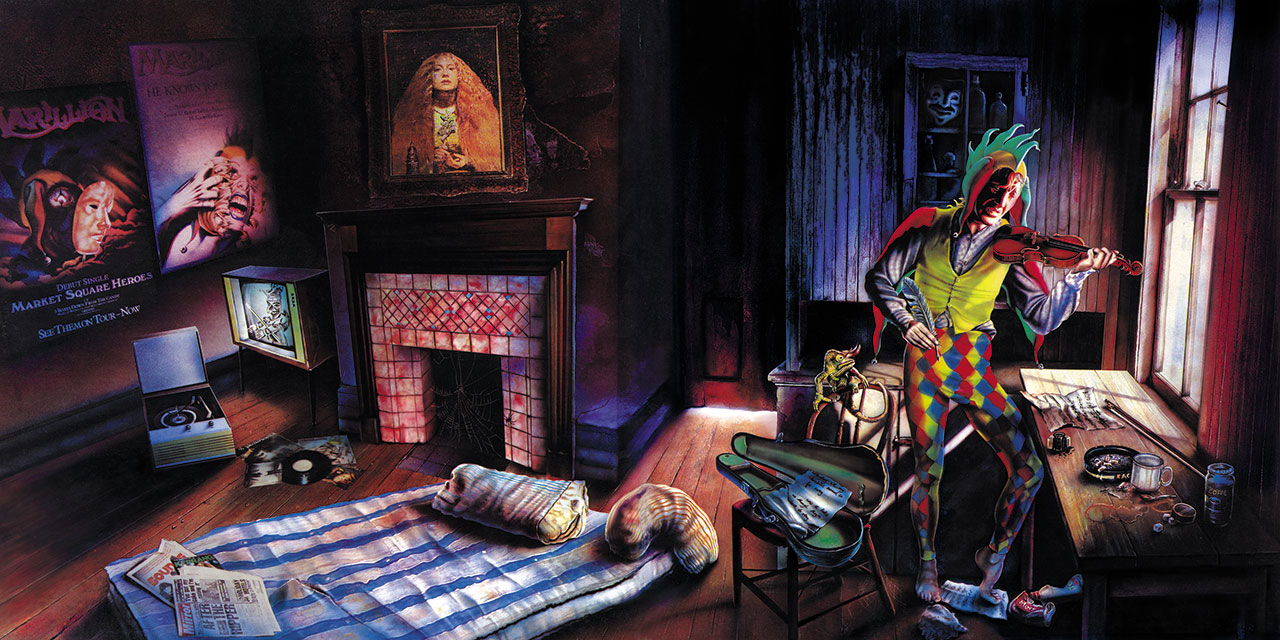

Marillion’s first single was released on October 25, 1982. It captured both sides of the band’s character, with the catchy, up-tempo Market Square Heroes and Three Boats Down From The Candy showing a more immediate side to the band, the lengthy take of Grendel a startlingly mature take on classic prog. It was housed in stunning artwork from a young artist called Mark Wilkinson, whose jester character went a long way to establishing a visual identity for Marillion, which would last for Fish’s entire tenure with the band.

“I think Mark Wilkinson’s covers in the early days helped establish a strong visualisation for the band,” says Rothery. “I think that really helped. It gave us a very strong identity. All the different cards had to fall in a certain way for things to happen. You realise, when you look back at it, all things had to happen for you to achieve a certain level of success; well, even to get to release a record, never mind having any success with it.”

None of the songs from that first single would appear on the band’s debut album. Nor would David Hitchcock. The producer unfortunately suffered a car accident when actually delivering the master tapes of the single to EMI, which prevented him from working on it. Nick Tauber, who had previously worked with Thin Lizzy and Toyah, was brought in to produce the record, which was done at their home away from home, Marquee Studios, above the club of the same name.

“It was a great studio,” states Fish. “It felt like the right move. We were in our London sanctuary. I remember when we played Script live on stage for the first time. Coming off stage, you go straight into the studio, which was good. It was a really good vibe.

“We were getting into all sorts of shenanigans there. I remember phoning up the secretary for the Marquee for the He Knows You Know thing. We did a lot of shit. We wanted a couple of Floyd-style effects. We wanted to get the announcer in for doing the spoken-word bit before Forgotten Sons and shit like that. It was a lot of fun building it.”

Recorded between December 1982 and February 1983, debut album Script For A Jester’s Tear was released on March 14. Two weeks later it was nestled at number seven in the UK album chart, a phenomenal result for a progressive rock band in the early 80s. In the space of three years, Marillion had gone from a local pub band to – which they would do at the end of the Script UK tour – headlining two nights at Hammersmith Odeon.

There was, of course, one remaining blot on the horizon. With cracks apparently evident during the recording of the album, drummer Mick Pointer, the founder of the band, was given his marching orders at the end of tour. It was a move that clearly still hurts him.

“It crushed me, absolutely,” Pointer says tersely. “I was so disgusted by the way people could be. You could be just discarded that quickly.”

“I think,” Trewavas muses diplomatically, “there was a situation and a feeling within the band, and also within the record company, that the band needed to grow and to move on. And the same with members of the band as well, and didn’t feel that Mick was advancing and growing in the same way that the rest of us were. So it was probably time. We had to grow quick and become more professional and more polished with everything we were doing. And there were kind of signs that Mick was struggling rhythmically at the time.”

“They were right about Diz,” adds Fish. “When we brought Pete in, being a better bass player than Diz, it showed how weak Mick was. Everybody we were bringing in was showing the weaknesses in other people in the band.”

Marillion would work their way through three more drummers before finally settling on former Steve Hackett man Ian Mosley, who remains with the band to this day. Former Camel drummer Andy Ward joined in May 1983, solidifying the early Camel link. But by the end of the US Script tour it was apparent that the rigours of touring were too much for him to handle. He played percussion when Marillion played as special guests on the Saturday at the Reading Festival, with former Voyager/Alaska drummer John Marter behind the drum kit. Marter remained for Marillion’s stint supporting Rush in North America, but was replaced by American drummer Jonathan Mover for one gig in Germany, before Mosley was introduced four weeks later. (Mick Pointer would resurface in successful UK prog rockers Arena, who have enjoyed a 20-odd-year career thus far.)

Marillion’s line-up remained solid for a further five years. They released three more studio albums, hitting the top spot with Misplaced Childhood in 1985 (they also reached number two in the UK Top 40 with Kayleigh) and following it with the number two album Clutching At Straws in 1987.

Fish and Marillion went their separate ways following a show at Craigtoun Country Park in July 1988. Relations between the two have roller-coasted occasionally since then, but in 2007 Steve Rothery, Mark Kelly, Pete Trewavas and Ian Mosley performed Market Square Heroes with Fish in Aylesbury’s Market Square at the Hobble On The Cobbles.

Both Fish and Marillion have had enduring successful careers since then. But the achievements of the men who formed Marillion during the first three years of their existence remain pretty remarkable in this day and age.

“There was a real buzz about it,” says Mark Kelly.

“It’s pretty crazy, really,” smiles Steve Rothery.

And you know, he’s probably right.

This feature originally appeared in Prog issue 104. Steve Rothery’s photos are taken from his book, Postcards From The Road, which is available to buy now.