Christmas 2008 was a solitary but spectacular affair for Marilyn Manson. Cocaine bags were nailed to the walls of a temporary, otherwise empty home, on which he had also scrawled the lyrics to his latest album. In the course of Christmas Day he cut his face and hands with a razor 158 times – once for every heartbroken phone call to Evan Rachel Wood, his 21-year-old ex-girlfriend. His ability to turn his body and home into morbid art even when he was at such a low ebb was impressive. The depression of a man who had previously enjoyed his excesses was, though, undeniable.

Regaling a journalist with his Christmas tale a few months later, Manson mentioned a $200,000 drug habit. “I have nothing,” he said. “I’ve lost everything, and I’ve got it back, and I’m happy to live in a hotel.” He arrived at a London hotel to meet the British press in June 2009 high on absinthe and cocaine, with a woman tossed over his shoulder and ranting with rare incoherence. That same month, two days before his world tour was due to start in Berlin, his record label had no idea where he was.

Old friends had now become dismissive of this once-iconic figure. “Drugs and alcohol now rule his life and he’s become a dopey clown,” said Trent Reznor, producer of Manson’s seven-million-selling breakthrough album, Antichrist Superstar. “He used to be the smartest guy in the room.”

A year later, Interscope Records dropped Manson, reflecting his steadily plunging sales through the 21st century. His importance to a generation of disaffected kids became harder to remember. The rock star formerly known as Brian Warner had once been a lightning rod for America’s most oppressive and dangerous forces. He was smart and articulate enough to withstand the verbal attacks and death threats from those who viewed him as the embodiment of everything that was rotten in the world. His intellectual armour-plating was never stronger – or more necessary – than when he was erroneously accused of inspiring the Columbine High School massacre in 1999.

But since 2000’s Holy Wood (In The Shadow Of The Valley Of Death) it had been a downhill run. His marriage to burlesque star Dita Von Teese in 2005 lasted a year, their divorce prompted by Manson’s affair with 19-year-old actress Evan Rachel Wood. He couldn’t even manage the usual rock-star compensation of decent break-up albums. Eat Me, Drink Me (post-Von Teese) and The High End Of Low (post-Wood) were woeful in every sense. “I started to think I don’t have feelings any more,” he confessed in 2009, “so why bother?”

In 2012 came Born Villain, trailed as a return to form. It was nothing of the sort. Manson’s state of mind was summed up in the title of one of its tracks: Disengaged.

Now, in 2014, the Antichrist has suddenly awoken. His new album, The Pale Emperor, really is his best in at least a decade. The leaden industrial rock template of recent times has a new gleam. There are tunes, and focus, and lyrics aimed with gleeful precision.

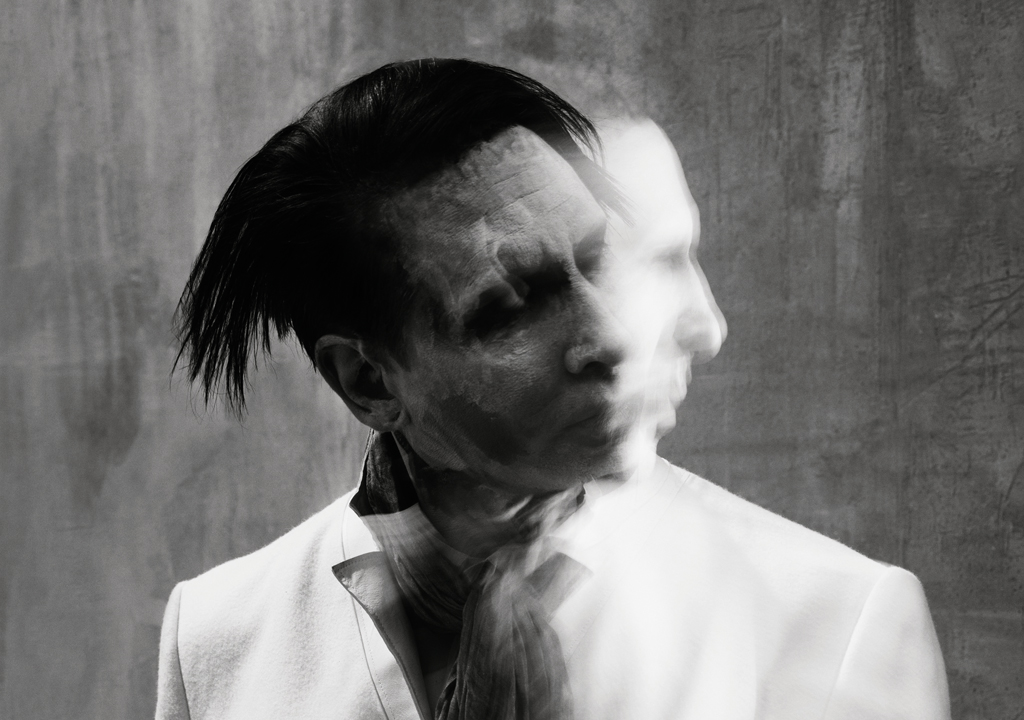

The Manson who slips into his barely lit Kensington hotel room with Nosferatu suddenness has no women dangling from his shoulder, no substances dripping from his nose. Sitting with his white face looming close, illuminated by the one light he’s turned on, he murmurs steadily, neither gibbering nor garrulous, but quietly contained.

The downside is that Manson is not in nakedly confessional mood. As he sings on the new album’s The Mephistopheles Of Los Angeles: ‘I don’t know if I can open up/I’ve been opened too much.’ Nor does the record company woman sitting in the room help, flashing a winding-up signal the moment we mention cocaine. The clock is ticking loudly as we try to get to the heart of Marilyn Manson’s resurrection.

He’s certainly as well-read as ever. Jokey congratulations that The Pale Emperor means he finally outranks the Thin White Duke provokes a long, learned riff on Caligula. The Mephistopheles Of Los Angeles, which updates Faust’s pact, was the original title track and the album’s heart.

“If we stick to the Faust story,” he says, “and if I had been in that story, and I had sold my soul for fame and fortune, and had the arrogance of the character in that story to not want to pay back the deal, it’s taken a few years for me to acknowledge to myself that I was hearing: ‘Manson [rapping his knuckles on the table], the hell hounds are on your trail.’ And this record is my payment. This is me giving back what I was given, or took, I’m not sure. Faust and Mephistopheles both exist within me. You can’t outrun your demons. You’ve got to deal with them eventually.”

What evidence had he seen of Satan scraping at his door, asking for payback?

“The evidence is in me acknowledging that I needed to make something that was up to my own expectations, my own rules. If you believe in some mythology, and you want to live by those commandments, I had to say myself: ‘I’m not really doing what I set out to do.’ And I tried to convince myself that I was. I’m not regretting the last few records that I’ve made, but since Holy Wood… I’ve not made something with the sheer utter fearlessness and anger and force [of before].”

Does Manson recognise, then, that the decade from his divorce to his new album was a worse era for him than the 90s?

“Well, time is so difficult for me to understand,” he says. “It’s not linear for me. I mean often [gesturing to the shrouded darkness of the room] we have this, and I couldn’t tell you what kind of day it is. But I think part of me is trapped. I’m still in the cycle of when I started this, aged twenty-three, when I left home and went on tour. And I’ve never really acknowledged the passage of time. On this record I do notice it. And I enjoyed that era of my life. There are parts that were great, parts that were bad. But I said to myself that I believe it is more important to be a person who has everything to gain than someone who has nothing to lose. So I made a record with that feeling.”

Whatever Manson’s put himself through, self-pity isn’t on The Pale Emperor’s agenda.

“This record was me not writing about it. Writing something with swagger and confidence, without any fear like a peacock or an elephant, who does not have knees, so that they cannot kneel before any God… I read that once in a Jungian book about dreams,” he adds, in an aside you’re unlikely to hear from any other rock star. “I knew the story that I wanted to tell, because it was my story, that anyone could understand, like the blues. The story is, you enter this world and you’re alone, and at the end of the day – spoiler alert! – you die alone.”

The chain of events which led to Marilyn Manson rediscovering who he was and what he did best had a lot to do with his Vietnam veteran father, Hugh Warner, who made an epic road trip in 2014 from the family home state of Ohio, deep in the conservative Midwest, to Los Angeles. “I didn’t know why he didn’t fly,” Manson muses. “He said because he wanted to spread my mother’s ashes on Route 66. Because my mother died on Mother’s Day – thank you mom.”

Manson was watching Francis Ford Coppola’s 1979 Vietnam film Apocalypse Now when his dad arrived.

“I was at the scene where Robert Duvall’s on the beach, where Charlie doesn’t surf. Bombs are going off, and he doesn’t even react to it. And I pressed pause, and my father walked in. And my father said: ‘This is the most accurate portrayal of Vietnam.’ And he said that it was very difficult to be someone who would kill people, and then come home and be expected to live a normal life. And I’d never had an explanation from my father about that.”

Manson asked his dad to smoke pot with him – incredibly, a drug the singer had never tried.

“He told me things that I had never heard before, in my whole childhood. And I said: ‘Dad, you’re going to like the record.’ So while a song on it like Killing Strangers is not to do with him, the record became so much about my father and my mother.”

The desire to bond with his dad also led to Manson’s part as a white supremacist in the FX biker show Sons Of Anarchy. The three-month shoot led to profound changes, which help explain his current personal and creative health. Basically, he had to get up for work.

The record company woman is pacing towards us now. But there’s still more to uncover. Manson isn’t the sort to undergo a Lou Reed-style conversion, and condemn the substances he once consumed. Holier than thou isn’t exactly Manson’s style. But his bright mood, with hints of Californian therapy-speak replacing the old sacrilegious incitements, suggests the new album was made by a whole new him.

“I stopped drinking absinthe about five weeks ago,” he admits. “There was too much sugar in it. I watched a documentary about how sugar affects the human brain, and absinthe has more sugar than vodka, so I switched to vodka. But that doesn’t mean I’m sober. I think it’s more to do with the reason I go to fight-training. I just wanted to become more… aware. Your brain synapses start firing off differently, and you find yourself less in need of the filler which the dopamine and adrenaline synapses need. My friends who know me well don’t understand. ‘You’re training, and you’re awake at noon. Who the fuck are you?’ Well, surprise. Just when you thought you knew me, you don’t.”

Manson was a good friend of Hunter S Thompson before the gonzo author of Fear And Loathing In Las Vegas shot himself in 2005. Even Thompson’s legendary constitution, and art, eventually suffered from his prodigious drug and drink intake. Does that help explain Manson’s own, desperately unfocused recent work? The man who once viewed his binges as glorious decadence admits he had already made serious efforts to rein them in, hinting at a visit to rehab (though a hint is as far as it goes).

“Well what I learnt, when I was bored, when I went to a mental hospital, to rehab,” Manson replies, “were the simple rules. Drink when you’re in a good mood, not when you’re in a bad mood. And don’t smoke crack, because it makes you poor. Cocaine also – it actually makes you poor. And heroin you’ll die, and Methadone makes your teeth look terrible. I’ve never smoked meth or done heroin in my life, because I’ve had too many of my friends die of that shit. That was based on simple observation, not judgement.”

Synapses now firing on all cylinders, rehab a faint memory, The Pale Emperor was made by a responsible, sharp Manson. “I realised that I need to focus more on creating than destroying,” he says. “In the past I was dreading going to the studio. This time you could not stop me. If there were a wall of naked women, I would say: ‘Fuck that. I’m going to the studio.’ But there was never a wall of naked women…”

“We are going to have to cut it there,” orders the record company woman, now standing right over us.

“One more question?” I ask mildly.

“If you’re really quick,” she grumbles.

“If you give me a vodka,” Manson laughs. “Vodka and one question.”

Here goes. In the period when he was releasing those weak albums that The Pale Emperor has pulled him clear of, did the man who was once at the heart of American outrage feel his cultural potency fading?

“I don’t think people remember something I did yesterday, let alone ten years ago,” he says. “Let’s compare me to a dick. Potency, heart – no Viagra needed. This new music is my payback to my deal with the devil, or whatever metaphorical box I have created for the past. I came here to kick people’s asses. And I needed to remember that.”

The rumble of rush-hour traffic is starting up outside, but Marilyn Manson suddenly sounds like he isn’t going anywhere. He sounds not like the God Of Fuck, but like the sort of son a straight-backed, Midwestern, Vietnam-veteran dad could be proud of.

“I’m the type of person that stands by their morals. I have a set of rules, if someone tries to fuck with what I believe in, what I love. You have to be willing to die for what you do. Do I want to die? No. Am I easy to kill? No. If you fuck with me will you get hurt? Probably. I protect what I care about. And that’s a man who stands by his morals. And those morals are dictated by me, and not by some bogus religion, or some egos, or some people I don’t know.”

“It’s my dad’s favourite show!”

How Marilyn Manson ended up on Sons Of Anarchy.

Manson’s make-up-free performance as jailed white supremacist Ron Tully in FX’s hit Californian biker series Sons Of Anarchy – the nearest thing now on TV to Breaking Bad – is his most serious acting role so far. And the requirements of a role very different to his usual image changed him.

“They didn’t really tell me much about my character,” he says. “I knew he was in the Aryan Brotherhood, and that was it.

“I showed up, and I had this haircut [part crew-cut, part floppy fringe] already. They said: ‘You look perfect. I said [mock-outraged]: ‘What are you trying to say? That I look like a racist?’ But it’s an ironic part for me, obviously, because I would not blend in well in prison.

“I became really tight with the guys on the show. Charlie Hunnam [lead biker ‘Jax’ Teller], Tommy Flanagan [‘Chibs’ Telford] and Mark Boone Junior [‘Bobby Elvis’ Munson] embraced their characters, because it’s been seven years of their lives. They weren’t these tough biker characters before they were cast. It affected them. As it would affect me, being who I am. I only worked on it for three months. But they stood up for me, you know, if there was a situation. These guys had my back.”

And does his character meet an appropriately twisted end? Apparently not. “I haven’t seen my last episode,” he says. “I know I don’t die. But I do go out strong.”