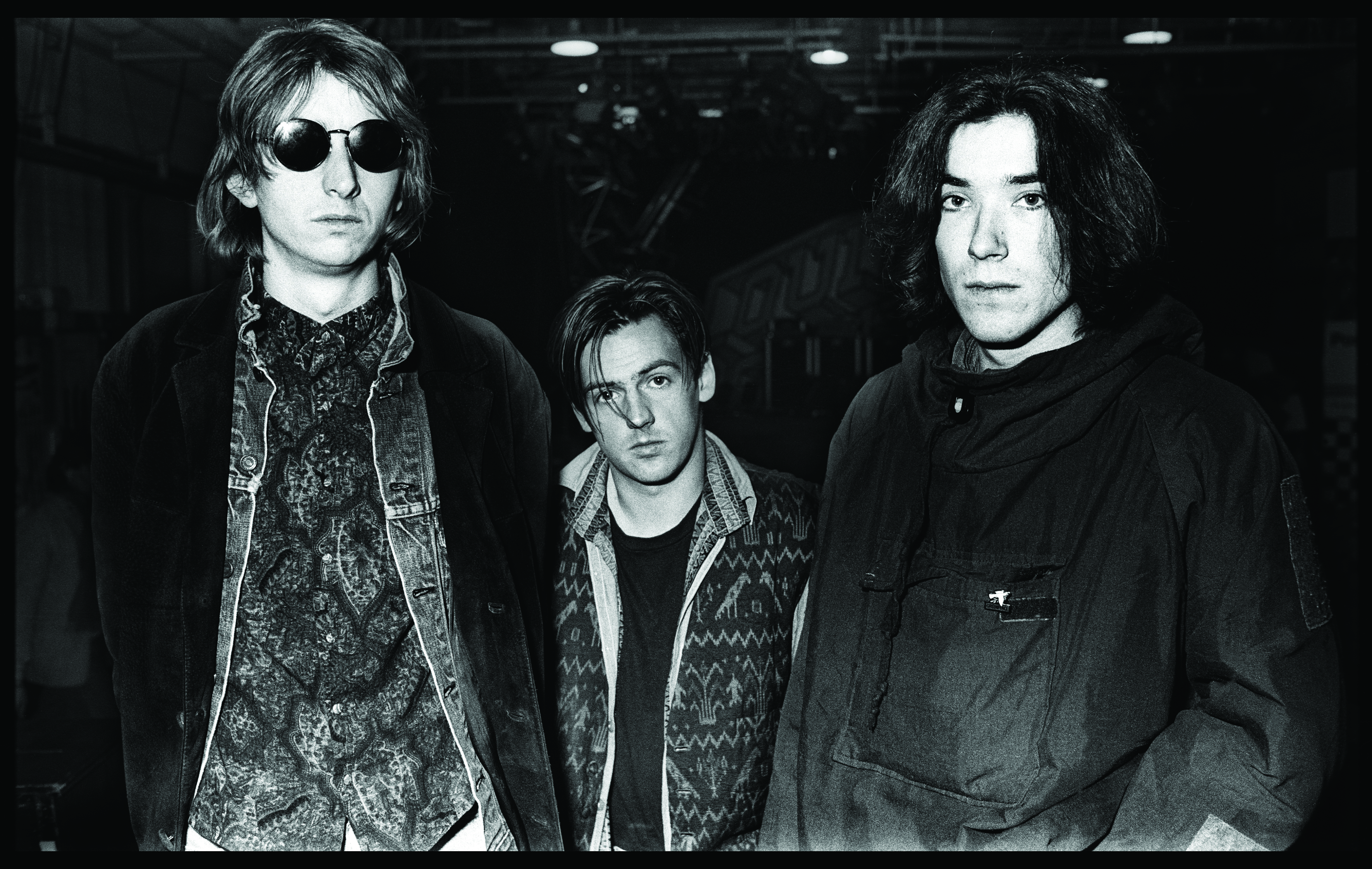

Few heard it coming in the early music of Talk Talk, whose 1982 debut album The Party’s Over, a slice of now-dated synth-pop sheen that wanted to be Roxy Music’s Avalon but landed on Midge Ure’s Ultravox, was described by critics as “a mess”, “airless” and “a laughable pomposity”. (To be fair, one spotted “a gothic, almost celestial majesty”.) Yet by the time the band’s “career” – for want of a better word – had ended 10 years later, they had transformed into something radically more exploratory and, to this day, quietly influential. Recent obituaries of Mark Hollis didn’t shy away from claiming that his passionate pursuit of an almost impossible ideal redefined rock.

“I never met Mark Hollis but always had the feeling that he was a co-tunneller under the surface of what pop music might mean,” tweeted Peter Hammill upon hearing of Mark’s death, aged 64, in late February. Musicians united in respect, emphasising the range of Talk Talk’s reach, from prog to pop to post-rock to all who seek to tweak the envelope. “Real originality is a rare commodity in music,” Peter Gabriel, who’d seen the young Talk Talk open for his Six Of The Best reunion show with Genesis at a rain-sodden Milton Keynes in October ’82, told The Guardian. “Mark created very personal pictures with his music and magical voice: a wry, unique and soulful take on the world.” Steven Wilson, who spoke of his love of the band when collaborating with Opeth’s Mikael Åkerfeldt as Storm Corrosion, commented that it was hard to think of any musician to whom the word “integrity” would more appropriately apply. “I still think Spirit Of Eden is the most admirable ‘fuck-you’ to the pop mainstream ever made. And I loved Mark for it. His records still stand for me as the most beautiful pop music ever made, albums where every musical gesture seems somehow sacred. Listening to them changes you forever.”

That music today floats hallowed and revered in a kind of eternal Elysium, but it wasn’t always this way. On one level, in one dimension, Talk Talk were an 80s band, existing from 1981 to 1992. Yet it’s hard now to think of music that sounds less typically 80s than theirs. Sure, those early albums were of their time, shepherded by the record company towards the New Wave-New Romantic overlap that the likes of Duran Duran (early label-mates) gobbled up. But before long they were constructing those later, organic landmarks, with Hollis declaring that he’d disowned synths. They’d been “an economic measure. Beyond that, I absolutely hate them. To me the only good thing about them was they gave you large areas of sound to work with. Apart from that they’re really horrible.” A recent eulogy from Roland Orzabal of loosely comparable generational peers Tears For Fears did not dispute Mark’s incongruity. “He was a god among so many mere mortals of 80s music,” he said. “In fact, to brand what he did with Talk Talk as ‘80s music’ is to discredit the genius that seeped out of his melodies and lyrics – lyrics that sometimes barely made it out of his mouth, as though he wanted to keep the world’s best secret all to himself.”

Talk Talk, everyone’s favourite secret, had travelled so far by the climax of their trajectory that their later work tapped into something profound, transcendent. Whispered and wailed confessions, psalms and exhortations spring from their depths, with that voice more gospel than pop, the fragmented musical structures aware of the codes of jazz and progressive rock but emanating from what might be a blinding light in a subterranean cave. Musicians were first bewildered, then awed as the sounds found the sweet spot in your soul, as the jigsaw started to fit.

The death of Tottenham-born Hollis has ended the hopes of many that he, or Talk Talk, might reappear one day with new music. In reality this was never likely to happen. Hollis all but retired from music after his one solo album in 1998, and seems to have happily turned his back on an industry with which he was patently uncomfortable. It’s too easy to label a musician a Syd Barrett-style “recluse” just because they haven’t been releasing albums and doing interviews: he was, for example, a keen and not antisocial motorcycle enthusiast. A fellow member of that informal club, upon realising who Hollis was, gushed that he wanted his music played at his funeral one day. Hollis laughed, benignly. He’d moved on. It must have seemed to him like a memory from youth, living in another world. And while more of his music would, for us, have been intriguing, there is a beauty in achieving perfection in what you set out to do then leaving it there, having said what you wanted to say. He’d advocated the spaces between, the silences, the parts you leave out. Never good at the promo game in an era when it was vital, he told one interviewer, “If you understand it, you do. If you don’t, nothing I say will make you understand it. The only thing I can do by talking about it is detract from it. I can’t add anything. Can I go home now?” For the last 21 years, he went home, his masterpieces done.

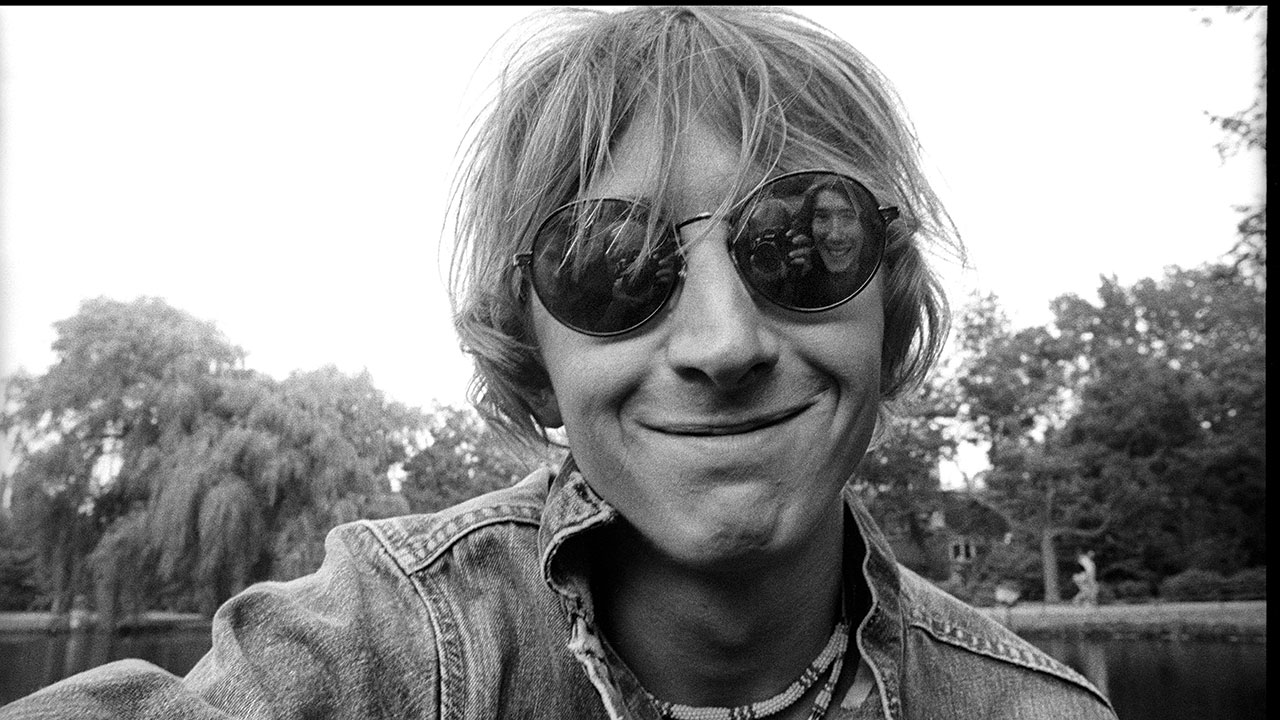

Even in those formative years, something in Hollis’ keening voice already suggested he had more sorrow and joy to express. As baggy-suited peacocks, however, sent out on tour with Duran Duran, they were gauche. “We just got caught up in a whirlwind,” he sighed. They were assigned Duran’s producer Colin Thurston, and were OK with that because he’d engineered Bowie’s “Heroes”. Hollis always felt awkward with the press. Choosing favourite records for brightly lit pop mags, he’d opt for Shostakovich, Faure, Walter Carlos, Augustus Pablo, Keith Jarrett. Asked for his hobbies, he replied, “Thinking.” Favourite groups? “Minorities.” Journalists meeting him would report back of an ordinary, unpretentious bloke, anything but a mystical guru, who was affable and content talking about football but would become reticent and defensive when it came to discussing his music. He didn’t comprehend why it wasn’t allowed to speak for itself. Now, it is.

There was always a link with prog. That early show with Genesis may have been something of a nightmare on the day, the atrocious weather fuelling the disgruntlement of an audience who took it out on the support act, but there’s a discernible bittersweet, happy-sad element shared by Gabriel’s more subtle slow numbers, Genesis’ melancholy moments like Entangled, and the emotion Hollis would display on something like April 5th, the song named after his wife’s birthday on The Colour Of Spring.

Before Talk Talk crafted that tightrope of tenderness and reached that level, they worked through 1984’s It’s My Life, getting into bed with dancefloor-remix culture, even though songs like Dum Dum Girl and Such A Shame were riddled with remorse and regret. And it was 1986’s The Colour Of Spring on which the doors of Hollis’ cage were flung open, and all kinds of odd animals, birds and insects – echoed by James Marsh’s classic cover art – tumbled out. Life’s What You Make It and Living In Another World pulled off marriages of euphoric big beat and eccentric, left-handed shifts. Between these bold lines, flickers of their music’s future murmured through on fragile, floating elegies like Chameleon Day.

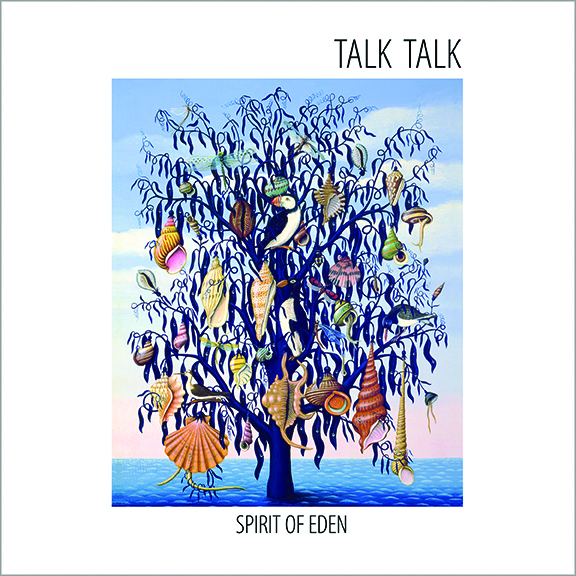

It was a success on every level, going gold, without which the subsequent albums would have remained an imaginary ideal in their creator’s mind’s eye. EMI provided the budget. When 1988’s Spirit Of Eden revealed itself, they had regrets. Famously, Hollis and co-writer/producer Tim Friese-Greene were imposing evangelically bizarre studio routines (or anti-routines): there are tales of disorientating strobe lighting, of players being brought in and not hearing the track, being told to improvise over nothing. Many hours of tape, often including Hollis’ vocal, were cut until Hollis and Friese-Greene were content. (One berserk aside is that Friese-Greene’s previous production work included Tight Fit’s chart-topper The Lion Sleeps Tonight. From “wimoweh, wimoweh” to Spirit Of Eden is a hell of a leap.) “We thought we’d broken the mould and could turn the tide of history,” the producer said later.

A neo-religious fusion of gospel, classical and prog tropes, The Rainbow, Eden, and I Believe In You are musical edifices that cause your jaw to hit the floor while your soul is showered in exaltation. Even now – and it’d be a hard-hearted Talk Talk fan who’s played them since Mark’s death without experiencing something in their eye – the album teases out new treasures with each listen. (Contrary to myth, it wasn’t universally panned by critics. Reviews ranged madly, nobody quite sure what the “correct” response was. It was called “ambient jazz-rock”, “elusive” and “uncommonly beautiful”. “Apparently these songs touch on everything from paradise to heroin addiction,” wrote Q, “yet all remain within the album’s mood of calm won from the storm.”)

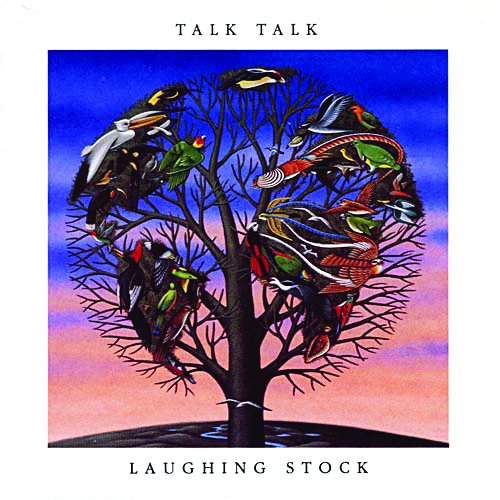

Now understood as an artist who didn’t compromise, Hollis (having switched labels) re-engaged for the swansong under the Talk Talk name, 1991’s archly titled Laughing Stock. If Spirit Of Eden created post-rock, this created post-post-rock. Sparse, intense, it drew a new map. Seemingly random shapes coalesced into something quite magical. Tim Bowness told this writer, “Each successive statement sounded purer and more focused than the previous one. There was an ongoing process of reduction in the music that reminded me of how Samuel Beckett continued to pare down language in his later work. [The sound] made most everything else around them seem so artificial that it was sometimes difficult to listen to anything else without being irritated by over-production or stylistic affectations.”

Minimalism was now manna to Hollis, and after the (by then notional) band’s split, his self-titled 1998 solo album (originally mooted for release under the band name) inched towards intimacy. That year he came close to describing his ethos: “Before you play two notes, learn how to play one. And don’t play one unless you’ve got a reason to play it.”

He took his own advice, embracing silence. Everything he struggled to communicate verbally was there, is there, in the music. Happiness, desire, hope, belief. He walked away to a quiet(er) life in South-West London because “I choose my family.” The family of musicians remains indebted to his short but stunning period of industry. He was once asked his favourite musician. “Kate Bush,” he said. Kate Bush was then asked hers. "Mark Hollis," she said.

When I co-authored the book Spirit Of Talk Talk in 2012 with the band’s artwork virtuoso James Marsh and Toby Benjamin, a lengthy queue of musicians lined up to pay homage, from The The’s Matt Johnson to David Torn, from Orbital’s Paul Hartnoll to Elbow’s Guy Garvey, from members of Depeche Mode, Bark Psychosis, Arcade Fire, Underworld, Doves, Bon Iver, Shearwater, UNKLE and The Verve to Robert Plant. “What he was doing was spectacular,” exclaimed Plant. “Laughing Stock – my god!”

Steve Hogarth noted that Talk Talk “ran the gamut from synth-pop to uncompromising art. Along with The Blue Nile and Japan, they…redefined how contemporary music could be written and arranged. The Colour Of Spring is meticulously produced but with an enigmatic, intense spirituality. It’s an object lesson in minimalism.” For Richard Barbieri, who knows a thing or two about Japan, “Spirit Of Eden and Laughing Stock are, quite simply, works of art. They have such an exquisite beauty about them, a complete and powerful understanding of space. There’s magic at work here. No matter how many times I listen to these albums I find myself totally immersed and entranced.” Even the late Rick Wright of Pink Floyd was on record as declaring his admiration. “Simplicity with a twist. Pink Floyd have never done anything that straightforward, because I tend to put a lot of sound colour into the music. In some ways, this type of stuff is braver because there’s nothing to hide behind. It touches me… but makes me feel happy.”

The word ‘genius’ is bandied around too readily. In this case, immersion in those last three Talk Talk albums insists it’s entirely appropriate regarding Mark Hollis. That music, stroking and scratching the sublime, is deathless. It touches you, but makes you feel happy.