Matthew Trippe died in December 2014. You may not recall his name immediately – if you even recall it at all – but for a while in 1988, the story he had to tell was one of the strangest of a long, strange era. Trippe claimed that earlier in that crazy decade, he had replaced Nikki Sixx as the bass player in Mötley Crüe.

Not as a stand-in or a new member, but as a doppelgänger chosen for his physical resemblance to the ‘original’ Nikki, just after the latter had been injured in a car accident and at the exact point that Mötley Crüe began the meteoric rise that would end with them becoming one of the biggest rock bands in America.

It was a story that brought Trippe a brief, bright notoriety but one that came to shadow the rest of his life, which faded in a long, slow and sad decline. It began, he said, in 1982, when he left home in Erie, Pennsylvania and moved to Los Angeles, where he met guitarist Mick Mars, who brought him into Mötley Crüe because the other Nikki had been injured in a car accident. It was a wild year that would conclude with Matthew in jail for armed robbery, abandoned by the band and their manager Doc McGhee, and with the original Nikki Sixx back in place.

Life for Matthew since those days had not been easy. He hadn’t looked like Nikki Sixx for a long time. His hair was cut short and had gone back to its natural brown colour. The tattoos that once replicated Nikki’s had begun to fade. He’d had a hip replacement. His health was not good. He’d been an alcoholic for many years. Occasionally someone would remember his story and ask for an interview – a Scandinavian radio station, a US podcast – but those were rare now.

Of all of the people that I met and interviewed during that era, famous and half-famous and unknown, Matthew John Trippe remained the most mysterious, interesting and perplexing. The world may not have believed what he had to say, but I believe that he believed it, and that in itself is an odd kind of truth.

Doc McGhee sounds tired. On the morning that we speak, he has taken an overnight flight from South America to Los Angeles and then headed straight for his office. He hasn’t been the manager of Mötley Crüe since 1989, but such was the impact of the madness of those years that their names remain bound together.

“So Matthew Trippe is dead?” he remarks. “Well, I’m sorry to hear that…”

Matthew’s story had broken at a bad time for McGhee and Mötley Crüe, who, by the early months of 1988, were selling millions of records and enjoying an apparently enviable neverending party, their every wish indulged by the benevolence of fame. They were a chaotically brilliant train wreck of a band living exactly the kind of nihilistic lifestyle that their songs captured so perfectly.

Nikki Sixx – the real one, the man born Frank Feranna – was in the grip of a heroin addiction so severe that his heart had stopped following an overdose a few months earlier, while singer Vince Neil still had the shadow of a vehicular manslaughter conviction hanging over him, after a drunken car crash which killed his passenger, Hanoi Rocks drummer Razzle. Mick Mars had his own problems – the guitarist was suffering from a debilitating form of arthritis that was slowly fusing his spine.

The whole band had recently left Japan in disgrace after an incident on a bullet train when a bottle of whiskey was hurled at a passenger’s head. A European tour had been cancelled at the last minute because McGhee and his business partner Doug Thaler feared that “some of [the band] would come back in body bags” if it went ahead. The “official” explanation given by Mick Mars was “too much snow on the roof” of the planned London venue, which if nothing else offers some insight into the lunacy that surrounded them.

It wasn’t just the band who were living on the edge. On April 25, 1988, McGhee would himself plead guilty to being part of a gang that had smuggled 29,000lbs of marijuana into South Carolina, accepting a five-year suspended jail sentence, a $15,000 fine and fulfilling a community penalty by staging the famously over-the-top Moscow Music Peace Festival, at which his biggest clients, Mötley Crüe and Bon Jovi, were to top the bill.

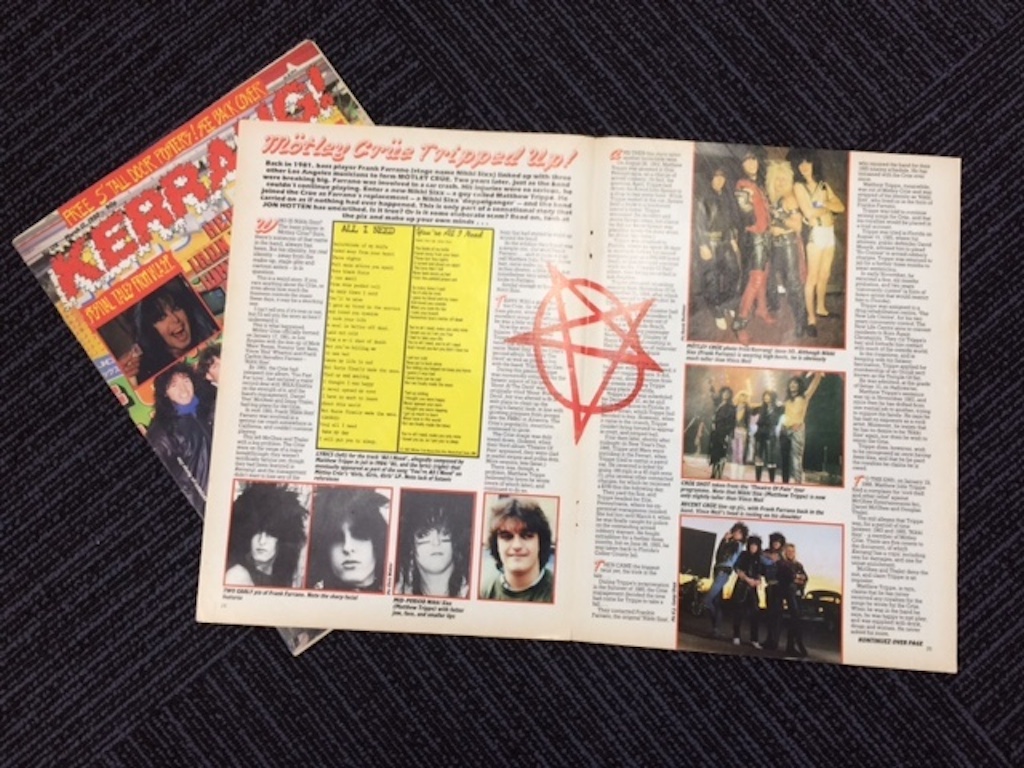

The entry of Matthew Trippe into this circus was incendiary. His story was first published in Kerrang! magazine on March 12, 1988. A lawsuit that claimed he had been a member of Mötley Crüe from some point in the spring of 1983 until April 1984 was filed in Florida at around the same time.

“He sued me, he didn’t sue Mötley Crüe,” McGhee says today. “He said that when he was in jail, I replaced him with Nikki Sixx as we know him now. He said he’d written all these songs and so on. They [the band] were all upset by it, but particularly Nikki. We had a lot of distractions. The drug abuse and the stuff that was going on with the guys… [Matthew] just added to the craziness.

“It went on for a couple of years,” McGhee continues. “I’d never met the guy. This was all news to me. I didn’t really look at it [the case] because it’s so far-fetched, especially when you’re there. It’s not like you go: ‘Well, I wonder if he really was Nikki Sixx?’ Then we had a deposition. He was there. And then right after that deposition, they threw the case out. It was weird enough managing Mötley Crüe as it was. This was just the icing on the cake.”

Matthew Trippe took the Greyhound bus to Los Angeles in the summer of 1982. He wanted to be a rock star, and LA was the place to become one. He was 19 years old and a wild kid. He’d been adopted at a young age, as was his sister Karen, and he felt like he didn’t fit in. His father was a dentist with a lucrative practice. Trippe Sr was strait-laced and strict, and Matt was closer to his mom, who played piano and taught him about music. But she dressed him in expensive clothes and he was picked on in school. He had a bad stammer, which made things worse.

He bought a book about Satanism for a dollar at the local thrift store and began to study it, which didn’t sit well with his Catholic parents. He began to fight with them because he wanted to know who his real parents were. He forged cheques from his father’s account and sent them to the Church of Satan. He took up guitar and made Gene Simmons his personal hero. Music and Satanism became places he could go to escape the clamour in his head. As a teenager, he was thrown out of the private school that his father was paying a thousand dollars a year for, and then in public school he became involved in a feud with another boy, broke into his house and caused thousands of dollars’ worth of damage with a Samurai sword. He was sent to various medical centres and halfway houses to have his mental health assessed. By the time he left for Los Angeles, he’d already run away from home several times.

It was in LA that Matthew Trippe’s story about becoming Nikki Sixx had its origins. What follows is his version of events (a version, we should stress, that was eventually thrown out of court).

With nowhere to stay and little money, Matthew brought a cheap car and slept in it. He spent a lot of time in Sunset Strip club The Troubadour, making one beer last an afternoon. It was there, in early 1983, that he said he met Mick Mars. Mick seemed quite old, but he had a band that had just signed to Elektra Records. Trippe hadn’t heard of Mötley Crüe, but that was because he’d been in Erie, Pennsylvania, and Crüe weren’t yet famous outside of LA. One night, Mars was bummed out because the band had lost their bass player; he’d injured himself in a car accident. Mars asked Matt if he could play bass. Matt said: “Sure.”

He said that Mars took him to an office in LA where he’d played four or five songs in front of the band’s manager, Doc McGhee. Afterwards he’d sat in reception on his own for what seemed like ages, and then Doc came out and told him he was the new bass player in Mötley Crüe. He gave his some papers to sign. When he began to write ‘Matthew Trippe’, Doc stopped him and said he should sign as ‘Nikki Sixx’.

Matt went to live in an apartment with Tommy Lee. He memorised the backstory of the ‘real’ Nikki Sixx, which was not a million ways from his own. He did some interviews. He drank beer and got stoned. The band were writing a new record called Shout With The Devil. Doc asked Matt to work on some songs so he wrote one called Danger and another called Knock ’Em Dead, Kid. Mötley Crüe had a little pentagram logo that was the wrong way around and Matt showed them the proper Satanic way, with the two points turned upwards. He suggested changing the name of the album to Shout At The Devil. They finished the record and made a video for the song Looks That Kill. Released in September 1983, Shout At The Devil got terrible reviews but made No.17 on the Billboard charts. Mötley Crüe went on tour with Kiss, where Matt met his hero Gene Simmons. When he went to visit his parents in Florida at Christmas 1983, he proudly told them he was in one of the biggest new bands in America.

He bummed around for two weeks with a girl called Cherry and a couple of hitchhikers he’d met. In January he rejoined the band and they went on tour with Ozzy Osbourne. Ozzy disliked him, he said, and so he got angry and trashed a few hotel rooms. The tour ended on April 1, 1984. The tour manager, Rich Fisher, came up to him and told him that he was out of the band because the original Nikki was coming back. Trippe thought it was an April Fool’s joke.

The next part of his story – his criminal history – was verifiably real. Matt went back to his mother’s holiday home in Fort Myers where he met up with Cherry and the hitchhikers again. They were partying one afternoon when they ran out of beer, so Matt drove the hitchers, whose names were Jeff and Chris, to a mall in Naples to get more. Jeff and Chris robbed a magazine stand and Matt drove them away. A few days later, they did it again. They all went on the run.

Together, Matt and Cherry drove to a hunting camp outside of Erie where no one would find them. Jeff and Chris showed up a few days later. Matt was showing off to Cherry, jumping off the roof of one of the cabins, when he broke his foot. Lots of people started to come to the camp to party. Cherry got bored and started bitching at him. People stole his beer.

Rumours started going around Erie that Nikki Sixx from Mötley Crüe was in town. Cherry went home. A few days later, Trippe was picked up by the police and was extradited back to Florida. The court made some kind of mistake with the papers and so he was released on bail. He bought a music magazine, and read that Mötley Crüe had gone on tour to Europe. He called Doc. Doc told him “the show must go on”. Trippe asked Doc for a lawyer. No one came.

As Trippe awaited trial, Vince Neil was involved in the car accident that killed Nicholas Dingley – better known as Razzle, the Isle Of Wight-born drummer with Finnish glam-punks Hanoi Rocks – and seriously injured two others: Lisa Hogan and Daniel Smithers. Neil eventually received a 30-day jail sentence and five years’ probation.

Trippe himself was sentenced to two years’ house arrest for the robbery. He skipped town and went back to Erie. He was arrested again, and remained in jail until he was sent back to Florida to complete his house arrest.

A year passed. Mötley Crüe released the Theatre Of Pain album, which included some more songs that Trippe alleged he wrote, such as Save Our Souls. He claimed to have called up Doc McGhee, who told him that the royalties would be coming in “soon”. And then he began telling people his story. Word went around that he was a lunatic, a fantasist, a fraud. He had to finish his sentence in a court-appointed rehab facility in West Palm Beach, where he was made to cut his hair and where they took away all of his photos and lyrics and magazines.

It was while he was in rehab that he joined the Temple Of Set, a Satanic church run by a former US army officer called Michael Aquino. Aquino called the Temple Of Set “the intellectual wing of esoteric Satanism”. It was Aquino and some others at the Temple who told Trippe what he should do: stop talking, grow his hair, lose weight and find a lawyer who could help him.

Matt met a private investigator named Jerry Oglesby. By then he had begun exaggerating his story, claiming that he had been the original Nikki Sixx and had formed the band. Oglesby soon rumbled him. Trippe told him the truth, as he saw it, and Oglesby began to gather evidence on his behalf. By the end of 1987, Trippe’s life had become more stable. He was married with a young son. He had management and a legal team and he was ready to go public with his story.

Soon afterwards, an envelope arrived on the desk of Geoff Barton, then the editor of Kerrang! (and later of Classic Rock magazine). Inside was a transparent folder containing a letter that outlined Trippe’s claims, plus some photographs and clippings from magazines that purported to show the changing physical appearance of Nikki Sixx. Geoff called me over. We looked through it. Parts of it appeared quite convincing. We had no idea who else it may have been sent to, so there was very little time to discover exactly what was going on if we were going to break the story.

The world was very different in 1988. Every desk in the Kerrang! office had a typewriter on it. Press releases arrived in the post or, if they were urgent, via fax. News was chased on the phone. The flow of information was far slower than today, its sources fewer. Details that are available now with one click on a Wikipedia page – the real names of the members of Mötley Crüe, for example, or lists of American tour dates – could take days to find.

Understandably, some of Matthew Trippe’s story was impossible to verify without weeks of legwork, and we didn’t have time for that. The most compelling part of it was the photographs he had provided. They appeared to show some physical differences in Nikki Sixx: in one he towered above Vince Neil, in another they looked to be almost the same height; a bare-chested shot showed Sixx with a protruding navel, another with an inverted one; a barefoot image showed toes of a particular shape, and another showed toes of a different shape (at least in the days before Photoshop, we didn’t have to worry about whether the pictures had been manipulated).

I wrote the story up, and we ran it not as the truth, but as the claims of an allegedly wronged man. The reaction to it was instant. The story was divisive and controversial. Everyone had an opinion on Matthew John Trippe. Other magazines picked up on it. MTV ran the story. Trippe had a kind of overnight notoriety. And he wasn’t the kind of person equipped to live with that.

“Well, you know, everything in the United States is a conspiracy theory,” says Doc McGhee. “People want to sensationalise everything, and there’s a lot of weird people out there. You’ll have a serial killer and someone wants to go marry them. It’s hard to tell what’s going on with a lot of people out there. Did Matthew ever give up on it? Did he ever admit that he wasn’t?”

The answer to that question is no. Trippe never did. Perhaps because he’d been telling the story for so long, the fantasy had blended with the realities of his life and Nikki Sixx became part of his identity. Yet he was the ultimate unreliable witness. When he had first met Jerry Oglesby and the other investigators who helped to compile his case, Trippe had said that he was the original Nikki Sixx, and had formed Mötley Crüe. Oglesby had quickly disproved that, but in the course of doing so he found other evidence – such as the photographs – that leant weight to Trippe’s case.

Then there was his stammer, which was noticeable almost as soon as he began speaking. He’d obviously had some sort of speech therapy, and it made his voice extremely distinctive – he would elongate words to eradicate the impulse to stutter. If he had given all of the interviews as Nikki Sixx that he said he had, then someone would remember it. Trippe said his stammer disappeared when he smoked marijuana, and that he’d been stoned a lot of the time in Mötley Crüe.

Nikki Sixx had been the architect of not just the band’s sound but also their look, yet Trippe cared little for clothes, and often seemed to dress in a way that a rock star of the 1980s never would: in baggy jeans and big T-shirts that hid his chunky frame.

I interviewed Mötley Crüe a few months after the Matthew Trippe story had run. “You write shitty things,” Sixx said to me when we met.

It was clear that he was in charge of the band. He instructed Tommy Lee and Vince Neil to speak to me together, and then he and Mick Mars. Mars said very little, and Sixx just sat there, his anger barely contained. It was unnerving. He was a big, strong guy. And as he was now clean, he glowed. His skin was clear, his jaw square. He was tanned and muscled, an all-American rock star. It was difficult to see how anyone could pass themself off as him.

Roger Hemond was 18 years old in April 1987 when he moved from Michigan to Tampa to try to become a rock star. The area had a little scene going: Savatage, Crimson Glory, Roxx Gang. He rented a place at the Abbey Apartments on Busch Boulevard, and almost as soon as he’d moved in he began hearing rumours that Nikki Sixx had once lived there too, and that Blackie Lawless, of W.A.S.P., had come to visit him. There were a lot of rocker types living at the Abbey Apartments, and they all seemed to believe it. Hemond thought they were nuts. Then he made friends with a guy called Richard Benjamin, who said he knew where Nikki Sixx, whose real name was Matthew Trippe, lived now. So Hemond and Benjamin went over there, but no one was home. Hemond began to hear all sorts of rumours about Trippe, including those that said there had been attempts on his life because he’d been claiming that he was Nikki Sixx.

A few weeks later a man named Carl Fisher showed up at the Abbey Apartments looking for Nikki. He had with him the photograph of Trippe on stage dressed in the black-and-white striped suit and sunglasses. Fisher had got himself into some trouble and had ended up in jail, where he’d met Trippe. When he got out he remembered Trippe’s story and decided to find him. Fisher had a business partner called Wayne Spillers who’d made a lot of money from nightclubs and managing professional wrestlers, and together they wanted to build Matthew Trippe’s post-Mötley Crüe career.

Fisher asked Hemond if he knew Trippe. Mindful of the rumours, Hemond offered to pass Fisher’s phone number to Trippe, and they’d see if he’d make contact. Hemond drove over to the house. Again got no reply, so he left a note tacked to the porch door.

A few weeks after that, a car pulled up at the Abbey Apartments and out got Trippe. He asked Hemond if he knew Richard Benjamin. His voice had quite a bad stutter to it. His hair was cut short. He’d gained a few pounds, and had a day job in a sandwich shop, but there was no doubt that he did look like Nikki Sixx – or at least how Nikki Sixx may look under those circumstances.

“Within a few seconds of being in my home,” says Hemond, “he’d taken a beer from the refrigerator without asking, sat down and put his feet up on my dining room table…”

Hemond was in a band called Sircor. They’d just lost their bass player. Trippe was looking for a gig. He put on a tape of a song called Black Widow that he said he’d written for Mötley Crüe and asked Hemond if he could play it. Hemond could. Within a couple of days, Sircor had become Sixx Pakk. Hemond understood that Trippe and his story would be a focus of the band, but he’d come to Florida to be a rock star, and now he had management, a huge rehearsal space, a PA system, a great new singer called Jim H, who was modelling himself on David Lee Roth, and a terrific drummer, Joe D.

They recorded a three-track demo in Morrisound Studios in Tampa. Former Quiet Riot singer Kevin DuBrow was there working with a local band called Juliet, and he ripped it out of Trippe: “Yeah, I was Lita Ford in The Runaways for two years…”

Still, the demo came out well, and soon they were getting calls from management telling them to be ready to go out on tour – with Crimson Glory in the US, or maybe some shows in Amsterdam and London. Labels such as Metal Blade and Roadrunner were expressing early interest.

But Trippe had a talent for self-sabotage. At one of the record company showcases he got angry and threw an $800 Hamer bass on the ground, snapping the neck from the body. At another meeting, Jerry Oglesby got into a fight with Jim H out on the street. Then Roger Hemond turned up for rehearsal one day and discovered that Trippe had sold the PA to pay for diapers and beer.

“He had this growing animosity toward the management and to anyone who tried to tell him what to do,” Hemond says of Trippe. “He was a spoiled child.”

The situation with the music was problematic too. Hemond wrote two of the three songs on the Sixx Pakk demo, and Jim H wrote the other plus all of the lyrics, but they were told to say that they were Trippe’s work. Hemond also had to show Trippe how to play various songs he claimed to have written or performed for Mötley Crüe, because he’d “forgotten” them. It all added to the mystery of Matthew Trippe.

“There are so many things that go either way with it,” Hemond says. “A guy trying to put something on, you’d think the last thing in the world he’d want to do was cut his hair. Matt would wear the worst thrift-store clothes; I mean, polyester golf pants with green and white check, and a maroon shirt. So un-rock star. He did not try to cultivate that. And his tattoos were legit, and identical.”

Trippe was also going for occasional dinners with Michael Aquino, the leader of the Temple of Set, and his wife Lilith. “Why would a former partner of Anton LaVey, who’d formed a church almost as large as the Church of Satan, have anything to do with an alcoholic weirdo? I have no idea.”

Trippe wrote one or two riffs, but, according to Hemond, “they were just not that good”. If he had once been able to write music and lyrics used by Mötley Crüe, then he couldn’t do it any more. He was more interested in drinking.

“Oh, Matt was an alcoholic, and he would not have denied that,” says Hemond.

Carl Fisher and Wayne Spillers pulled the plug once Trippe began squandering their money. Hemond, Jim H and Joe D dumped him and formed a new band called Blind Sight. After Sixx Pakk folded, Matthew Trippe would never play in a professional band again.

“Carl had great patience with all of us, because we were all idiots,” says Hemond. “But we were very young men, and then there was Matt… If it hadn’t been for the extreme behaviour, we could have at least got an album and a tour out of it.”

I met Matthew face-to-face only once, in LA at some point in 1991, after I’d interviewed the real Nikki Sixx. Matt had little of Frank Feranna’s dark charisma. He was shorter than Sixx, and heavier, the weight gathered around his chin. He smoked constantly, holding his cigarettes between his middle two fingers. But he did look a lot like Nikki. He seemed confident about his case. He’d made an effort with the way he dressed, all in black. He tried to flirt with the girl I was with.

The years passed. Matthew’s name slipped from public view. After a fallow period during the time of grunge, Mötley Crüe’s fortunes began to change when they published an autobiography, The Dirt: Confessions Of The World’s Most Notorious Rock Band, in 2001, a book full of excruciating and terrifying detail that became a New York Times bestseller and began a genre of rock’n’roll confessionals that became as ubiquitous as a greatest hits album. Within a few years Crüe had been, if not restored to their pedestal, then at least re-evaulated as one of the great bands of the 1980s. Their status as the symbol of a lost but longed-for age gave them great commercial power and they are currently engaged on their final year-long farewell tour with their reputation as a keystone of American rock history assured.

Tellingly, The Dirt contained no mention of Matthew Trippe, but it made me wonder what had happened to him. I got back in touch with him via Facebook. We exchanged a few messages.

“The past is gone, done with,” he told me. He hadn’t had sex in “years” because women all thought that he had money stashed away somewhere. He felt that he’d been screwed over by a lot of people. He smoked too much and drank too much.

Trippe was aware that there was quite a lot of information and opinion about his story on the internet. There were people who believed him and there were people who didn’t. There were people who claimed to have seen Doc McGhee going into Matt’s house in the dead of night.

He put me on to a Scandinavian website that had three hours’ worth of interviews with him on CD. He said it was the best that he’d done. I sent off for them. When they arrived, his distinctive voice brought the whole story back. I had to admit that I was as interested in it as all of the other people digging around online – maybe more. But now the detail of his story could be scrutinised much more easily.

Some things seemed unlikely. For example, Mötley Crüe were working on the Shout At The Devil album in the latter part of 1982, as Matthew had said. But Doc McGhee and Doug Thaler did not take over as managers of the band until February 1983, so how could Matt have signed his contract in Doc’s office as he claimed? Nikki Sixx did injure his shoulder in a car accident, but that happened in June 1983, after the band had been on tour with Kiss. The tour that Mötley Crüe undertook with Ozzy Osbourne in the early part of 1984 became one of the most infamous of the era, well-documented by journalists and photographers, so surely there should be physical evidence of Trippe’s presence. Midway through that tour, the band had been presented with gold and platinum awards for Shout At The Devil, so where were Trippe’s? Nikki Sixx was in a relationship with Lita Ford for much of 1982 and 1983, so why had Trippe never mentioned her? And so on.

Yet Matthew, as Roger Hemond says, “had an almost savant-like quality” for remembering detail, and some of the things he said could make you think: “How did he know that, unless he was there?” He was telling a story about Vince Neil punching a female marine at the Troubadour long before it came out in The Dirt. He would pull out odd facts like Mick Mars’s favourite ice cream, or the name of the director of a particular video. There was the mystery of the photographs and the expensive tattoos; of his membership of the Temple Of Set, a fairly exclusive organisation (I emailed Michael Aquino, who confirmed much of what Trippe had claimed). None of that fitted with a penniless alcoholic from Erie, Pennsylvania.

Matthew Trippe wasn’t the kind of guy who could have done what the real Nikki Sixx – the kind of sharp, creative guy who shaped a very particular aesthetic that encapsulated and inspired an era of rock music – had done. I came to the view that if any of his story was true – and that in itself was a massive leap of faith – then at most he had in some way been around the band for a few days somewhere. Perhaps he had met Mick Mars at the Troubadour, or had got into a soundcheck or even a production rehearsal.

“Listen, people justify what they do all the time,” says Doc McGhee. “A guy walks into a 7-Eleven and rips it off for eighty dollars, he justifies it to himself. I think that Matthew Trippe believed he really was Nikki Sixx and wanted more of it. He found a couple of lawyers that believed him and we had to go through a couple of years of defending ourselves.”

Matthew Trippe’s lawsuit against McGhee Entertainment was dropped on December 10, 1993 when the statute of limitations on the case ran out. The closest Matthew came to his day in court was the deposition where he had sat opposite Doc McGhee.

“You can perhaps tell a lot by what’s not happened,” says Roger Hemond. “If he’d gone on tour at all, someone would have something, a picture, some VHS… Almost everything anyone had from those days has been uploaded on the internet. Matthew’s identity was compromised and he couldn’t get it back. He got to the point where he didn’t know what the truth was.”

In 2010 Trippe had started up a business repairing clocks and watches, but money was tight. He didn’t write songs any more, and didn’t play the guitar often either. Instead he loved to cook – he was terrific at that – and he loved his dog, Hammie.

In the summer of 2014, he was admitted to hospital with infections in his liver and pancreas, and underwent tests for cancer. Soon after his birthday, on September 18, his home was vandalised when a couple he’d invited to stay got into an argument with each other. His waterbed was slashed open and flooded the place, his door was kicked out and his gate damaged. He feared that he might be evicted.

Classic Rock was interested in a story on Matt and what had happened to him since 1993, so I messaged him to see if he’d be willing to talk. I thought he would be because he still loved the intrigue that surrounded him. He usually responded quickly, but a couple of weeks drifted by.

On December 1, I checked his Facebook page and found a message from a friend announcing his death. He’d been admitted to hospital in Naples, Florida, with a bleeding ulcer and a failing liver and been put on life support. He never recovered. He was 51 years old.

Matthew Trippe died with his mystery intact. Not the mystery of whether he had been Nikki Sixx, but the mystery of why he’d wanted to be, and why that desire had come to consume the reality of his life. As Doc McGhee told me on the phone: “In the eighties there were a lot of people who would say that they were Axl Rose or they were Vince Neil. There were a lot of people who just liked to have that little bit of fame.” There were lots of others who were desperate to make it as rock stars or VJs or managers or promoters, too. The lure was powerful and seductive, a yearning that was fuelled by the bands that lived it and the media that celebrated it. Some people became lost inside of it, and Trippe had just lost himself in a very unusual way.Those days are long gone. Mötley Crüe retired at the end of 2015 (Nikki Sixx declined to be interviewed for this piece). Doc McGhee looks after Kiss and a roster of bands that actually want to be managed. Roger Hemond still plays with Jim and Joe in a group called Thrown Alive. Carl Fisher, manager of Sixx Pakk, passed away soon after Trippe. Matthew himself leaves behind a now grown-up son.

“And one of the saddest things is that, to my knowledge, he never sat down and wrote some songs as Matthew Trippe. He was a musician and he loved music. Whether he was a good musician or not in the end doesn’t matter.”

This article originally appeared in Classic Rock #212