This article first appeared in The Blues #7, June 2013.

Mavis Staples has just finished recording One True Vine, her second album with Jeff Tweedy, the producer, songwriter and leader of the Americana band Wilco. The album’s 10 songs bristle with an emotional commitment and passion that has remained undiluted since the rich-voiced contralto first started performing with The Staple Singers.

“It doesn’t matter if I’m singing a gospel song or a message song or a love song,” says Mavis down the phone from her home in South Side Chicago. “Whatever I sing, it’s going to sound like me, it’s going to be positive and uplifting, it’s going to have meaning and it’s going to come straight from the heart and the soul.”

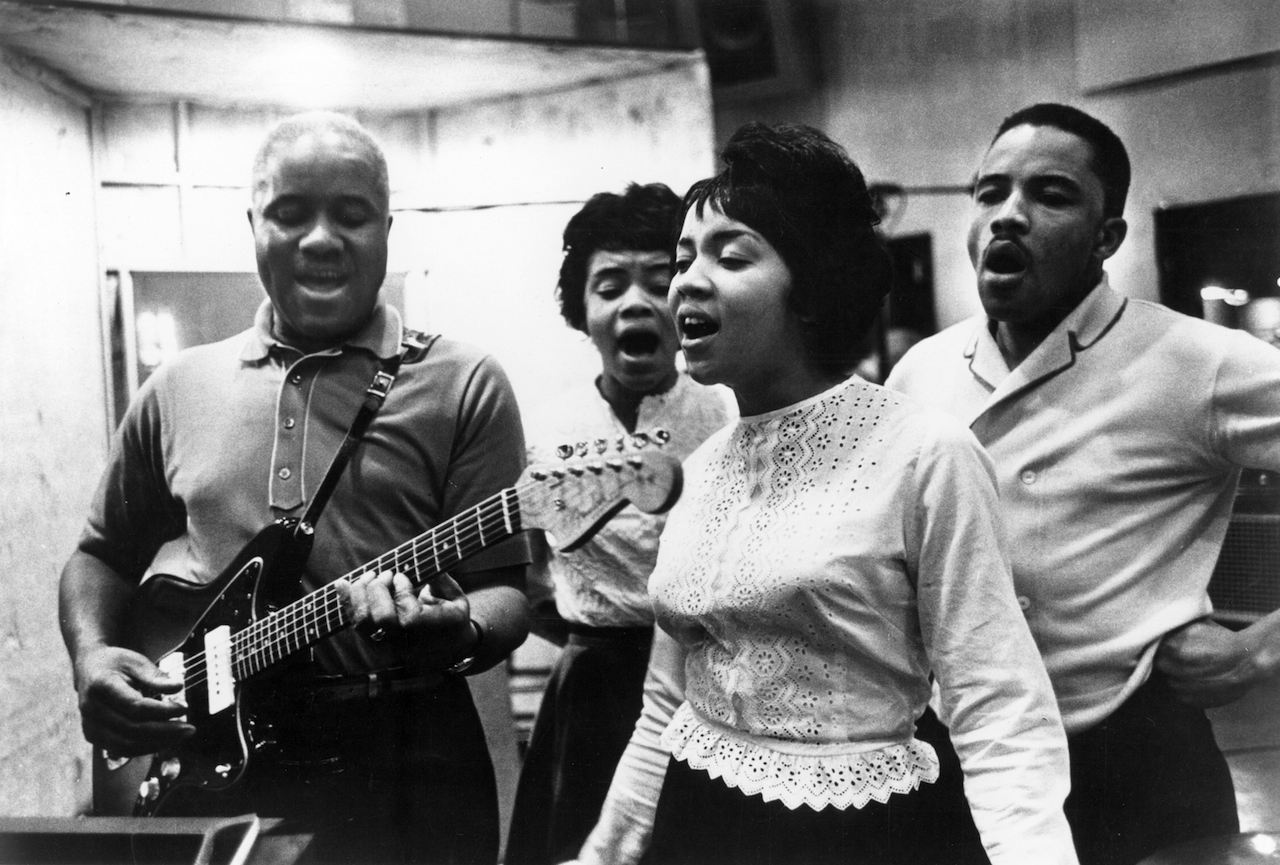

The Staple Singers were formed in 1948, when Mavis was just nine. Built upon her raw, gutsy vocal and her father Roebuck ‘Pops’ Staples’ pure tenor and bluesy guitar playing, the quartet’s line-up was completed by Mavis’ siblings Pervis and Cleotha until in 1970 Mavis’ younger sister Yvonne Staples replaced Pervis.

The Staple Singers gave gospel music its first million seller with 1956’s Uncloudy Day for the Vee Jay label then, after seeing Bob Dylan perform at the Newport Folk Festival and Dr Martin Luther King preach in Montgomery, Alabama, they aligned themselves to the civil rights movement, writing such message songs as Freedom Highway and Why (Am I Treated So Bad) and covering Stephen Stills’ For What It’s Worth.

On signing to Stax in 1968 they married political clout to commercial success – 1971’s Respect Yourself, a black pride anthem, made the US R&B No.2 spot while 1972’s I’ll Take You There and 1973’s If You’re Ready (Come Go With Me) made No.1. Come 1975, the group were topping the charts again with the soundtrack to the film Let’s Do It Again, recorded with Curtis Mayfield for his Curtom label.

By this time Mavis had already recorded two solo records – 1969’s self-titled debut for Volt and 1970’s Only For The Lonely on Stax – and as The Staple Singers’ performances grew fewer in the 80s, she forged ahead as a solo artist, working with Eddie Holland, Lamont Dozier and Brian Holland (1984’s Mavis Staples) and Prince (Time Waits For No One in 1989 and 1993’s The Voice). She also paid tribute to Mahalia Jackson (1996’s Spirituals & Gospel: Dedicated To Mahalia Jackson with Lucky Peterson) and recorded the bluesy Have A Little Faith for Alligator in 2004.

Then in 2007, on signing to the Anti label, she recorded We’ll Never Turn Back. Produced by Ry Cooder, it saw a return to the freedom cries she had sung on the frontline in her youth. Its follow-up, 2010’s You Are Not Alone, produced by Jeff Tweedy, is arguably her finest album and the equal of her work with The Staple Singers.

“Working with Tweedy, well he’s a cut above, he totally gets me, he’s a great producer, a great songwriter, and he likes to challenge me. When we finished One True Vine, I drove home and just sunk into the armchair, and thought, well we’ve got nothing to worry about here, we’ve got another good CD.”

What was your first introduction to music and singing?

I was eight and I went to stay with my grandma in Mississippi. We went to church three times a week, this little bitty church on the hill called the Jerusalem Baptist church, and on a Sunday everyone would sing the old hymns. There was no piano, just a wooden floor, and people would pit-patter their feet on that wooden floor and that would be the drums, and they would clap their hands, which made the beat and the a cappella voices – that was the sound Pops gave us when we sang in The Staple Singers. We were the Mississippi sound, even though we lived in Chicago.

How did The Staple Singers form?

It started with Pops. He grew up in Mississippi, one of 14 children, and after dinner they would go out on the porch and sing harmonies and people from all around would come to listen to us. Then Pops moved to Chicago and he sang in an all-male group called The Trumpet Jubilees.

Each week he’d go to sing and no one would show up and he would come home disgusted and he’d go back the next week and the same thing would happen, and by the third week when this happened, he came home, headed straight to the closet where he had a guitar he’d bought at the pawn shop, and he calls us children into the living room, sits us on the floor in a circle and begins giving us voice parts to sing for Will The Circle Be Unbroken. These were the same parts he and his brothers and sisters had sung in Mississippi.

So how did you make the leap from singing, sat on that living room floor, to performing in front of an audience?

Pops’ sister, our Aunt Katie, lived with us and one night she comes in to listen and says, ‘Shucks, you all sound pretty good, I want you to sing at my church.’ So we sang at Aunt Katie’s church and the people liked us so much they clapped us back and we had to sing Will The Circle Be Unbroken three times as it was the only song Pops had taught us the whole way through. After that Pops said, ‘Shucks, these people like us, we need to go home and learn some more songs [laughs].’

Uncloudy Day was the one that crossed you over.

I sang bass on Uncloudy Day and people would hear the record and say, ‘That’s no little girl, that must be a man or a big fat lady’ and when we sang it live, Pervis would step up to the mic as if he was going to sing my part and then suddenly I’d run out in front of him and sing. It always surprised everyone. And the president of Vee Jay, she called Pops and said how Uncloudy Day was selling like an R&B record. It was the first gospel song to sell a million.

Mahalia Jackson was your first influence. You paid homage with Spirituals & Gospel: Dedicated To Mahalia Jackson with Lucky Peterson.

Oh yes, sister Mahalia Jackson was the first female voice I heard on record. Pops was always playing 78s in the living room and suddenly among all the male voices, there she was singing. It was amazing to hear, and I’d get Pops to play her again and again. Then a few years later we got to open for her at church and I really looked up to her. The way she lived her life was inspirational, travelling with Dr Martin Luther King, trying to change the world through her singing.

Seeing Bob Dylan at the 1963 Newport Folk Festival was also pivotal in your musical development.

We were standing over on the side of the stage talking and Pops said, ‘Wait a minute, listen to what that kid is saying,’ and we did and it hit me. I thought how awfully close to gospel his music was and the stories he told in his songs were just so true, they had so much realness, you couldn’t help but fall in love with what he was saying and the way he was saying it.

- Booker T Jones: The Hitman

- Religion: Aretha Franklin

- Buyer's Guide: Otis Redding

- Rock'N'Soul: 20 Soul Classics Rock Fans Will Love

It was his song Blowin’ In The Wind that struck a chord.

Oh yes, when he sang Blowin’ In The Wind, Pops said, ‘We can sing that song.’ Bobby was singing, ‘How many roads must a man walk down before you call him a man?’ and my father had literally lived that. He told us stories of Mississippi, where if he was on one side of the street and a white man on the same side was walking towards him, he’d have to cross over. We came home and learned Blowin’ In The Wind and Pops said he felt so good singing that song, he said, ‘this song is me’. Then we listened to A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall and Masters Of War and we sang them too.

Shortly after that you started writing and singing your own civil rights songs.

Yes. Bob Dylan was ahead of us! We went to see Dr Martin Luther King. We happened to be in Montgomery on a Sunday. We didn’t have to sing until the evening and we were in a hotel and Pops had been listening to Dr King’s radio programme. He said to us, ‘I like the way he speaks and I want to go to his 11 o’clock service, would you like to come?’ We all said yes and went with him. We went to the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church and we were ushered in and seated and we listened and at the end of the sermon, the congregation filed out, and Dr Martin Luther King is at the door to shake everyone’s hand. Pops stood and talked to him for a little while and when we got back to the hotel he told us, ‘I really like this man’s speaking and his message,’ then he said, ‘I think if he can preach it, we can sing it.’ We started singing freedom songs and we joined the movement. The first one Pops wrote was Freedom Highway.

Another important message song was Pops’ Why (Am I Treated So Bad).

Why that was Dr King’s favourite. We would sing before Dr King would speak, and just as we were leaving the hotel, he would tell Pops, ‘Wait a minute Stap, you be singing my song tonight right?’ and Pops would say, ‘I be singing your song.’

Then came your cover of Stephen Stills’ For What It’s Worth.

We were always listening to music on the radio or watching it on TV and when we heard that song, we said the same thing we said when we heard Dylan sing, because they were joining in, it was like they were in the movement. When we heard those lyrics, ‘There’s something happening here/What it is ain’t exactly clear/There’s a man with a gun over there/Telling me I got to beware/I think it’s time we stop, children, what’s that sound. Everybody look what’s going down’, it was like, ‘Woah!’. They resonated with us so much.

But unlike with Bobby, we didn’t know Stephen and Pops was worried. He said, ‘I don’t know if these guys will like us singing their song’ and we were like, ‘No daddy they won’t mind.’ When we finally met Stephen, he was so happy we’d covered it. It was the same with [The Band’s] The Weight. To this day I don’t know what the song is about. I even asked Levon [Helm]. I said, ‘Levon, explain The Weight’ and he said, ‘Mavis, please don’t ask me to do that. I think we just put a pile of words together and they came out good.’ My brother said, ‘I think they’re talking about drugs’ and I said, ‘Pervis, we can’t be singing about no drugs.’

You recorded six albums for Stax between 1968 and ‘74. What was that experience like?

It was great. We got there and Steve Cropper produced our first record [1968’s Soul Folk In Action] and we were so excited to meet them all, because we knew the music, but we didn’t know the people and to get over there after we had been singing our freedom songs and to see an integrated group in Booker T & The MGs. They couldn’t go in the bathroom or eat in a restaurant or stay in a hotel together, but they could sing and make music together. And it was just unbelievable to meet Otis Redding, William Bell and Eddie Floyd. We were in good company at Stax. You see, Pops thought Stax was an all black company because we joined because of Al Bell. Pops saw Al like a son, he was charismatic and smart and here was a black man running a company in Memphis. It was a good move, Stax were the best, and when the empire crumbled it was awful.

Tell me about Respect Yourself, your 1971 US R&B No.2 hit written by Mack Rice and Luther Ingram.

We were in the studio recording one day and anyone could walk in on the session. Otis would walk in and say, ‘Pops, you need to do this,’ and Pops would say, ‘Otis! Get out of here.’ Well Mack Rice came in and said, ‘Pops I’ve got just the song for you.’ Mack Rice, Luther Ingram and a few others had been talking and Luther said, ‘Us as black people, we got to start respecting ourselves.’ A bomb went off in Mack Rice’s head and that’s where the song came from. Well Pops hated that riff, the ‘Dip deedly dee deedly dee dee’ bit and he said that doesn’t sound like The Staple Singers but Mack, he kept saying the kids will love it and we finally persuaded Pops to play the riff and sure enough everybody loved that bit.

For us, it was about the lyric. ‘If you disrespect anybody that you run into, how in the world do you think anybody’s s’posed to respect you.’ Every lyric in that song is the truth.

What role did such songs play in the civil rights movement?

When we started singing those freedom songs we thought we could change the world. When we would march with Dr King and sing Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me ’Round, we felt we were doing something positive. Music gives that outlook, it motivates you and inspires you and can take you on a different route. The congressman John Lewis wrote the notes to We’ll Never Turn Back, he said to me, ‘Your family were the soundtrack of the civil rights movement, you inspired us to keep on going, you motivated us to keep on marching and singing those songs.’ It would be a terrible world without music. Music keeps you going. It helps you keep your head held high.

When Stax went bankrupt, The Staple Singers signed with Curtis Mayfield’s Curtom label, releasing 1975’s Let’s Do It Again, the soundtrack to the Bill Cosby and Sidney Poitier film of the same name. You’d known Curtis from when you were growing up in Chicago, hadn’t you?

Curtis was like my baby brother, he was a great poet and he lived around the corner from us. One day he came to Pops and said, ‘I want to write songs like The Staple Singers do,’ and Pops said, ‘Curtis man, you’re a writer, a poet, write those songs’ and the first one Curtis wrote [in that vein] was Move On Up, and Pops said, ‘That’s my boy!’

Anyway when Curtis told Pops his part on Let’s Do It Again – ‘Now I like you lady, so fine with your pretty hair’ – Pops said, ‘Curtis man, I’m not going to say that, I’m a church man.’ Curtis says, ‘Oh Pops, the lord won’t mind. I’ll pray for you.’ We really wanted to hear our voices on the big screen and we managed to talk Pops into doing it. Every time Pops sang it on stage, all the ladies in the audience would cheer and he would have this big grin on his face.

2010’s You’re Not Alone was an exceptional record and your first recording with Jeff Tweedy in his Chicago Loft studio. What makes you, Tweedy and The Loft such a magical combination?

Well Tweedy, he grew up listening to The Staple Singers as a teenager, he worked at a record shop and had access to our music, and he studied us. He came backstage after a show I did at the Hideout in Chicago, which I recorded for my [2008] CD Hope At The Hideout, and the following week I got a call from my manager saying he wanted to produce me. I knew Wilco and liked them and so we got together. He is just spot on when it comes to giving me something to do because he knows I live the life I sing about, he just drills right into that with his lyrics and brings the best out of me. So his lyrics are always powerful, like on One True Vine, he goes beyond with that track. Then you’ve got The Loft, oh man! When you walk in, you walk into a sea of guitars and Tweedy loves guitars how I love songs and it’s just like home, so cosy. I can go into the kitchen and make me some hot chocolate. I have my own corner in The Loft, Mavis’ corner, and no one is allowed in Mavis’ corner. My sister Yvonne, she sits on the couch as we rehearse and watches her soap operas on the TV. It’s always a fun time and a happy time for me when I’m there.

You cover Funkadelic’s Can You Get To That on One True Vine. Whose idea was that?

Now Tweedy brought that song for me to do on the first album and someone said, that’s not for Mavis, so we put it on the back burner, but this time, we listened to it again and I said I really like it. Because it’s got a really positive message, it’s really a gospel song, it’s got hope and liberation in that song and it was a great song to do.

You’re no stranger to the White House, having sung at the inaugurations of Kennedy, Carter and Clinton. You were back there in April celebrating Memphis music with President Obama.

Talk about having a good time! It was just great to see our old friends, I mean it was like a family reunion. I looked up at Eddie Floyd and his hair was white and I was like, ‘Eddie, you’re looking more like Pops every day’, and to see Booker T and Steve Cropper again and Obama, he had himself a good time. And even though I’d been there before, it is different with Obama. This is our first black president, I just cried.

Lastly, what does the future hold?

I want to sing a CD of Bob Dylan songs. I want to do a tribute because Bob Dylan is the greatest poet, he was the first to see what he could see as a kid and to be backed just by his own guitar playing. We sang with just my father’s guitar because Pops said, ‘I want the people to hear what we are singing, to hear the story in the song’ and you could hear what Dylan was talking and singing about. You lived what he sang.