“They’ve come over the water from Canada… Max Webster Band!” That was Radio 1 DJ Peter Powell introducing the Websters on Top Of The Pops in May 1979. Like many watching at home, Powell clearly didn’t have a clue who this deliciously odd band were, and might conceivably have thought – erroneously – that one of them was actually named Max.

Led by flamboyantly dressed singer/guitarist Kim Mitchell, and big on unique, often surreal lyrics written by poet and honorary band member Pye Dubois, Max Webster had somehow hit No.43 in the UK singles chart with Paradise Skies. A breezy, virtuosic single from their fourth album A Million Vacations, it was a beguiling gatecrasher on a TV show which that night also featured ABBA and Art Garfunkel. The backdrop to the Websters’ chartgrazing coup was their ongoing UK support tour with long-term pals Rush, then out promoting their sixth studio album, Hemispheres.

Chatting to Max Webster’s Kim Mitchell today, Classic Rock reminds him of the flexi-disc samplers of his band’s music that were placed on seats when they played at Glasgow Apollo that year, and of that heady time when, for just a moment, it seemed that the Websters, sometimes described by Mitchell as “Rush’s little brother band”, might storm the UK.

“Yeah, it was a beautiful experience”, he says. “Top Of The Pops needed a British master of Paradise Skies for legal reasons, so we had to go into Abbey Road to re-record it through the night, then lip-sync to that version. Abbey Road! Can you imagine?”

Mitchell is talking at his home in Toronto. A framed drawing of Frank Zappa sits on the wall behind his left shoulder. Amiable and attentive, he’s happy to wander wherever our chat leads. As he adjusts his black baseball cap and settles in to answer our questions, a thought occurs to him:

“Can I say something about that Apollo show?” he asks. “I was a huge fan of the Sensational Alex Harvey Band, and I’d mentioned it before we got to Glasgow. After we played, there was a knock on our dressing-room door, and this little old guy walked in and said: ‘Hi, I’m Les Harvey, Alex’s dad.’ We grabbed some beers and I talked to him for about an hour. It was such an honour.”

Born in Sarnia, Ontario, Mitchell grew up just 40 minutes’ drive from the Canada/US border into Michigan. He was raised on Detroit rock acts such as the MC5 and the Detroit Wheels, plus lots of Tamla Motown. A stint backing “Greece’s answer to Tom Jones” took him to the island of Rhodes for 18 months as a teenager.

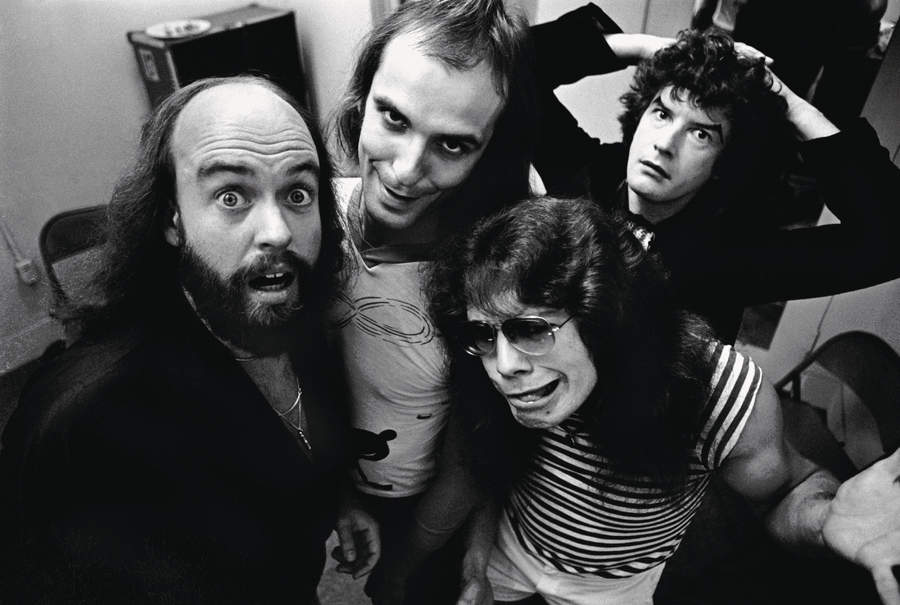

It was upon returning to Canada in 1972 that Mitchell formed Max Webster in Toronto with his childhood friend Pye Dubois. Airing their skewed hard rock and prog on the local bar circuit, the band soon hit on the classic line-up which comprised Mitchell, Dubois, keyboard player Terry Watkinson, drummer Gary McCracken and bassist Mike Tilka (who was later replaced by Dave Myles).

Mitchell loved Captain Beefheart’s daring, and Jimi Hendrix “because he changed guitar playing for ever”, and Max Webster’s touchstones were many and varied. In their infancy, they covered tricky Frank Zappa instrumental Peaches En Regalia, David Bowie’s Suffragette City and some songs by Jethro Tull. Their original material was equally striking. One early convert was Ray Danniels, then already managing Rush.

“The two bands were mutual fans,” said Danniels. “Ray came to see us play and he was like: ‘Okay, let’s do something! Let me take half!’ Those seventies contracts were quite something [laughs].”

Danniels duly signed Max Webster to SRO Management, and to Taurus Records, the label he had originally set up for Rush in North America. Rush’s then-record-producer Terry Brown would also produce the first four Max Webster albums, deepening the sense of an extended family.

When Max Webster’s self-titled debut was released in May 1976, it said ‘unique’ from the get-go. And not just because of keyboard player Terry Watkinson’s surreal cover painting of three-eyed, two-nosed human heads on a conveyor belt. Riff-tastic opener Hangover talked of ‘double vision when the bars close down’. Toronto Tontos was something else again, a bit like a hard rock band with a penchant for Weimar Republic cabaret. Elsewhere, part of Dubois’s lyric on Coming Off The Moon ran: ‘Shaved in photogenic lace, tying-off her arm, my lady luck did answer.’ Max Webster didn’t really do ‘Woke up this morning and my baby was gone,’ did they?

“We didn’t,” Mitchell says with a smile. “Our lyrics were rarely stories. Pye would just jam with the English language in this amazing way, painting pictures. I said to him one time: ‘Pye, where are you getting all this stuff?’ He said: ‘You just have to listen really well. People are saying these things.’ I was like: ‘They are? Really?’

“Pye wasn’t French by the way”, Mitchell adds. “His real name was – and still is – Paul Woods. I knew ‘bois’ was French for ‘woods’, but Iremember asking why he’d chosen the name Pye. He said: ‘“Pye-dog” is a term for a wild dog, and I’m the wild dog of the woods, man!’”

Max Webster soon undertook their first North American support tour with Rush. They travelled across Canada then down into the US. “The press was awful to them”, says Mitchell. “One guy wrote that Geddy [Lee] sounded like a cat being chased out the door with a blow-torch up its ass, which was just brutal. Incidents like that influenced our song On The Road [from 1977’s High Class In Borrowed Shoes], where the lyric goes: ‘I don’t need your assistance, to review the show.’

“Rush taught us that you should make your own decisions and not listen to record company bullshit. They were like: ‘This is our music, and these are our lives.’ The other thing I remember is that when we reached the US, the intensity of both bands’ playing was off the scale, cos we had something to prove. Canada was like the warm-up – you had hockey players skating around at sound-check and stuff [laughs]. But when we got to the Paramount Theater in Seattle – boom!”

Max Webster’s third studio LP, Mutiny Up My Sleeve (1978), further perfected their unique sound. A joyful exuberance propelled by Let Your Man Fly and The Party, the latter song nailed live at Seneca College, Toronto and featuring gung-ho audience participation plus some typically out-there Dubois lyrics. ‘Now Daphne is the orphan, still searching for her roots’, Mitchell sang gleefully, sleigh-bells jingling behind him. ‘She likes concert blisters and leather boots.’

The musical interplay on The Party was astonishing, Mitchell’s lead-guitar solo packing a jazzy fluidity, and Watkinson’s keyboards similarly playful. Years later, when Mitchell asked Gene Simmons why Kiss never took Max Webster out as support, Simmons was candid: “That’s easy – you were too good.”

Still, recording Mutiny hadn’t been without its challenges – not least because producer Terry Brown quit halfway through.

“We were doing Beyond The Moon”, recalls Mitchell. “We couldn’t get a take, and Terry, who was used to working with Rush, was holding the bar up really high. He said: ‘That’s it, I’m all done here,’ and left the session. With hindsight I think that was a bit unfair. It was just that we needed more time. But Terry and I are still good friends, and we talk often.”

A Million Vacations was the 1979, platinum-selling (in Canada) follow-up that yielded the aforementioned Paradise Skies, and also hatched another hit, Let Go The Line. Written and sung by Terry Watkinson, it was perfect for drive-time radio and reached No.41 in Canada. But it was also a tune that de-fanged Max Webster, shaving off their all-important kooky edges.

Happily the band’s next – and final – album, 1980’s Universal Juveniles, was Max Webster in excelsis, arguably their finest hour. You could tell Mitchell meant business because the front cover depicted him shrink-wrapped in yellow spandex running towards the camera. Accessorised with white leather ankle boots, his outfit was quite something; even The Darkness’s Justin Hawkins might have thought twice.

“People still ask: ‘Have you still got the yellow jumpsuit?’” Mitchell says, laughing. “Let’s just say that if I regret anything in life it’s that jumpsuit and what I wore on the cover of High Class In Borrowed Shoes [think zig-zag patterned crop-top and elaborately motifed tights].”

Universal Juveniles was produced by Jack Richardson, an experienced hit maker who had worked with Alice Cooper, The Guess Who and Badfinger. “Jack was very song-focused, and made sure that spontaneous energy was there. We took a lot of risks on stuff like April In Toledo, which is still one of my favourite things we ever did. I can remember the record company listening to Check [which begins with guitar-lead noise as Mitchell plugs in] and going: ‘Are you gonna keep that on there?’ We were like: ‘Of course!’”

The album was recorded at Phase One Studios in Toronto, and Mitchell recalls seeing Alice Cooper in the lounge, where a young kid sometimes joined the Godfather Of Shock Rock to play pinball. “I didn’t know it until years later,” Mitchell says, “but that kid was Keanu Reeves.”

Cooper and Reeves weren’t the only big names who showed. On July 28, 1980, during a huge thunderstorm, Geddy Lee, Alex Lifeson and Neil Peart joined Max Webster at Phase One to record the Mitchell/ Dubois-written epic Battle Scar. Both bands brought their best game as they responded to palpable magic in the air. Mitchell says the recording was a first take, “but then we did many more just for the fun of it. Two bands, all of our amps and two drummers.” he adds. “Pye said it sounded like a Boeing 747 taking-off.”

It was that same day, incidentally, that Pye Dubois first asked Rush if they might be interested in using some of his words. Then titled Louis The Lawyer, the lyric he presented them with was later reworked for Tom Sawyer, the celebrated opening track on Rush’s Moving Pictures.

After all this time, how would Mitchell characterise the relationship between Max Webster and Rush? Some wonderful shared adventures, obviously. But could it also be claustrophobic, a little too incestuous?

“No,” he says plainly. “Rush were great friends and they always treated us as equals. There were so many beautiful moments, and they made touring so enjoyable. I can still picture Neil with a book and a pack of cigarettes. He was an intense dude, but so sweet once you knew him. I remember one day Alex couldn’t make sound-check and I played Xanadu with Ged and Neil.

“When I talk about Max Webster being Rush’s ‘little brother band’, that’s a comment on how management dealt with us. I’m not saying for a moment that we got ignored, but we sensed that it wasn’t really gonna happen for us internationally and sometimes felt left in the dust.”

Scoring four gold LPs and one platinum one in their native Canada, Max Webster were hardly small beer at home. Internationally, though, they remained a cult band. But those who loved them really loved them.

It was directly after a 1981 support slot with Rush in Memphis that Mitchell decided to quit and go solo. “I walked into the dressing room and said: ‘I’m going home’. Their jaws all dropped. But I was burnt out. I’d been thinking of leaving all through that tour, but hadn’t said anything. I felt we’d taken Max Webster as far as we could. I was thinking is there more to life musically than this? What’s my next move?”

That next move turned out to be Kim Mitchell, an ace EP released in November 1982. Retaining the services of Dubois, and featuring such gems as Kids In Action and Chain Of Events, it kick-started a solo career whose success quickly eclipsed that of Max Webster. Mitchell sounded energised, perhaps a little miffed. By the time he released Akimbo Alogo, his debut solo album proper in 1984, he’d scored his first Canadian Top 30 single with Go For Soda.

When the follow-up album, 1986’s Shakin’ Like A Human Being, went triple-platinum in Canada, Mitchell mentioned some songwriting lessons he’d had from Rik Emmett, frontman with that other Canadian power-trio, Triumph. Between 1989 and 2007 he released five more solo LPs before settling into 11 years as an acclaimed drivetime radio host on Toronto rock station Q107.

“A lot of presenters would remove their headphones and go have a smoke”, he says, “but I didn’t. I sat there listening to Led Zeppelin and Heart at full blast.”

In 1995/96, Max Webster reunited for a tour that would mark the sad end of Mitchell’s partnership with Dubois. The pair had sometimes warred while making Mitchell’s solo records, but this was different.

“I know Pye really well, but I can only speculate as to what actually happened,” Mitchell says. “First of all, Pye doesn’t drive, so I was always responsible for picking him up. That was fine. But on the reunion tour he got a bit preachy and accusatory in the dressing room, talking about what had gone wrong with Max. Next day, Gary McCracken calls me and says: ‘Listen, I want these reunion shows to be fun, but Pye’s getting heavy – fix it.’ So I just didn’t pick Pye up that night. And then I got a lawyer’s letter saying: ‘Mr Dubois no longer wants any contact with Mr Mitchell…’”

In 2021, Mitchell and Dubois were inducted into The Canadian Songwriter’s Hall Of Fame. Mitchell attended the small, covid-postponed ceremony alone. “They told me Pye was invited, but he didn’t show,” Mitchell says. “In fact he didn’t even respond. I haven’t seen him since the reunion tour.”

Now 71, Mitchell is keeping well again after the heart-attack that derailed him in 2016. In 2020 he made his first album in 13 years with sometime Adele/ Taylor Swift producer Greg Wells, a long-term Max/ Mitchell fan and a former bandmate.

“I said, ‘I’m an old frost-bitten Canadian, I can’t afford you!’”, smiles Mitchell of working with Wells on The Big Fantasise. “Greg was like: ‘Don’t worry, let’s just do this and get the music to where we love it.’”

And what of Max Webster? Will Mitchell continue to perform their music live?

“My voice will go at some point, but until then I’m about customer service and rock’n’roll. I’m happy to play whatever people want to hear. Those songs are my kids, man!”