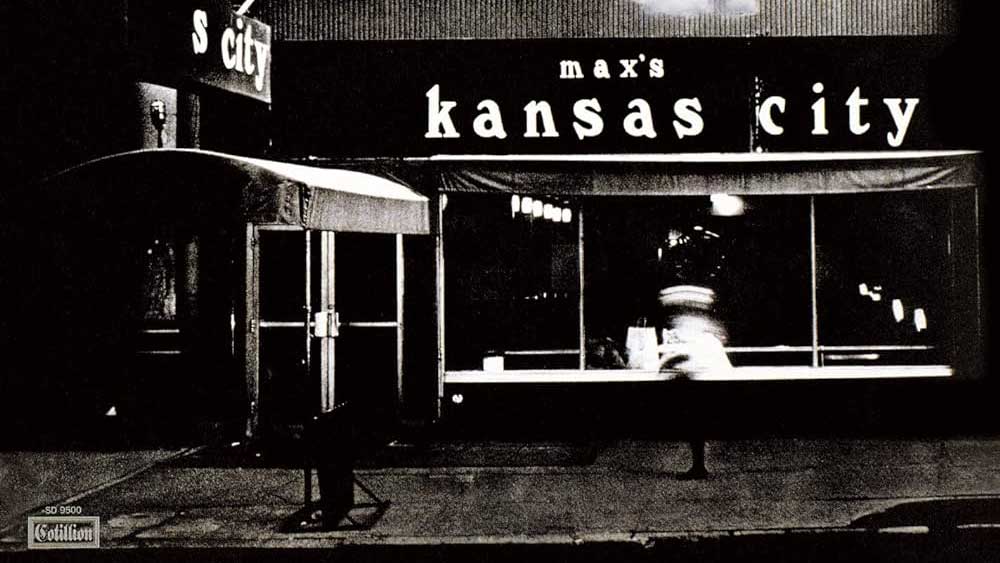

Anyone with even a passing interest in music is probably aware of famed New York club CBGB. Musicians, actors and even politicians got involved in trying to save the landmark venue before it closed in 2006. But look back another 25 years, to a time before celebrities lent their support to such worthy causes, and you will barely find a mention of another New York club, Max’s Kansas City, shutting its doors for the last time.

Yes, clubs close all the time. But Max’s was different. This place was about more than just music. Max’s was, as author William S Burroughs once said, “the intersection of everything”. Bar, club, restaurant, meeting place, gallery and landmark, Max’s was all these rolled into one mass of cultural resonance.

Originally opened in December 1965 by restaurateur and arts patron Mickey Ruskin as a safe haven for New York’s creative community, Max’s would embrace two distinctive eras before it finally called time in the early 80s.

The first was all about Ruskin and his love of New York creativity. It was a place where artists, writers and musicians could gather, muse about their art and eat without having to conform to anyone else’s standards. In the mid-60s the New York scene desperately needed a focal point, and that’s what Max’s gave it. As Mickey once explained: “My places have always been my living room, and every night I throw a party. But at Max’s it went from being an ordinary little salon and turned into magic”.

So what transformed Mickey’s “ordinary salon” into the most important venue of its day? Some have attributed its success to a mixture of luck and good timing – after all, this was an extraordinary time in American pop culture. Mickey’s former wife and soulmate, Yvonne Sewall Ruskin, has a clearer recollection: “Mickey had a mission, and it wasn’t about money because Mickey was not so great with money; he gave and gave – too much, in my opinion. For him it was about passion and commitment to his love for the artistic world.”

Within months, the word had spread that something special was happening in town, and Max’s began to attract every celebrity who came to New York. The Front Room became colonised by the East Coast’s most hip painters, sculptors and poets – many of whom would give Mickey their artworks in exchange for a bar tab. The Back Room saw Andy Warhol hold court, with Lou Reed, David Bowie and Iggy Pop, while a shy English piano player called Reg Dwight tinkled away on the piano in the corner.

Sandwiched in-between was The Pack, a bar where, before they got their breaks, Debbie Harry and Emmylou Harris waited on tables occupied by the glitterati of not only New York, but the whole world: Jagger, Lennon, Dylan, Zeppelin, Jim Morrison, Janis Joplin; writers from Truman Capote to Alan Ginsberg, William Burroughs to a young Cameron Crowe; Hopper, Pacino, Fonda, Beatty, and every young actor who fancied their chances in New York. Even the Kennedys got in on the act. The Pack even became the first bar in New York to introduce the ‘red rope’ – with a strict policy of ‘no jackets, no ties’.

Then there was Upstairs – home to The New York Dolls, and with the Velvet Underground in residency. Bowie was there, Tom Waits, Dylan, The Heartbreakers, The Stooges, Blondie, The Ramones, Patti Smith, Tim Buckley, the Wailers, The Doors… the list goes on. As Jimi Hendrix once remarked: “Max’s is where you can let your freak flag fly.”

News was spreading fast, and Max’s was becoming a living legend. It all left such an impression on then-writer Cameron Crowe that he knew he had to immortalise it on film.

“As a rock fan living in San Diego and freelancing for Rolling Stone, Circus and Creem, I knew the myth and allure of Max’s in a big way,” Crowe says. “Just by reading Lisa Robinson’s Rock Scene, I knew exactly how towering and deeply cool the place had to be. As I got to know the place, it became clear that Max’s was a place that a band or an artist needed to visit to truly ‘arrive’ in New York. That’s why I wrote Max’s into [his 2000 movie] Almost Famous. Stillwater could never have been a serious band playing New York until they had visited Max’s.”

For those privileged to be considered regulars, Max’s became a home in the literal sense. The free food given away during cocktail hour would often be the only meal some of them would get. Even Lou Reed once said that without Max’s he would have starved, as Mickey fed him every day for nearly three years. Musician, Playmate, famous mum and all-round rock’n’roll muse Bebe Buell credits Max’s as being where she turned from Southern belle into the ultimate rock chick.

“Max’s was my home," she said. "It is where I grew up. The first time I went was not long after I met Todd [Rundgren], and I remember catching a glimpse of this amazing red room. And when I peeked inside I couldn’t believe it. It was like nothing I had even seen before – sat around this table was Andy Warhol, Lou Reed, Peter Fonda and others. I couldn’t believe it. I had been in New York five minutes, and here I was in the same place as these guys. I was all star-struck. But they looked after me, they made me feel part of their group."

Over the ensuing years, rock’n’roll history became punctuated with tales from Max’s: Aerosmith signed their record deal after their first show at Max’s. An unknown Bruce Springsteen got his New York City break there, as did a young Billy Joel. Bob Marley first brought reggae to America at Max’s, while Sid Vicious’s infamous solo career came to its shambolic end there. Patti Smith going electric? That was at Max’s too. Where do you think David Bowie met Iggy Pop? After playing with the Stooges at Max’s, Iggy decided to roll in broken glass, and had to be taken to hospital by Alice Cooper.

In Walk On The Wildside, when Lou Reed sings: ‘Candy came from out of the island/ In the Backroom she was everybody’s darling’, Candy was Candy Darling, a Max’s regular. And guess where the Backroom that he was talking about was? When the Ramones had made a name for themselves at CBGB and wanted to take a step up, Max’s was that next step. And that doesn’t even touch on the influence Max’s had on movies, fashion, art and literature.

But as Yvonne Sewall Ruskin readily acknowledges, Mickey was no businessman. And with bar tabs often stretching to thousands of dollars, and more and more art being taken in lieu of payment, it was inevitable that even somewhere as magical as Max’s couldn’t keep going.

“Mickey’s generosity was his downfall, because people started to abuse it as do children who have no boundaries,” she says. “I did not like that he was too generous. It bothered me because it was not appreciated.” The queue of creditors grew. But unlike the CBGB situation, in the mid-70s there was no PR mileage for rock stars wanting to pretend to slum it by mounting a campaign, so eventually Mickey was forced to close down.

As Mickey’s involvement ended, a man named Tommy Dean ushered in the second era. After the strength of character that Ruskin had brought to Max’s, changes were inevitable. The old guard from the Backroom moved on. And just as Ruskin’s original had coincided with the ‘turn on, tune in, drop out’ generation, of the late 60s, Dean’s vision would also benefit from the arrival of a new generation – the group that would become know as The Blank Generation.

Original Ramones drummer Tommy Ramone was there: “It was a major loss to us when Mickey closed the place, as Max’s was our regular hangout. When it re-opened, Tommy Dean’s Max’s was different. He redecorated it, got rid of the chick-peas, put in ‘island bars’ so more customers could drink, and opened the upstairs for unsigned bands. Dean’s club became a rock hangout for the growing punk scene as well as the fading glam rock scene. The original Max’s was magic, but the new one was ours.”

But those involved with Ruskin’s Max’s would never even recognise it as the same place, as Yvonne explains: “The original had class and clout and serious-minded creative people, whereas the second incarnation was a music club with lots of heroin and no other disciplines in the arts.”

The one person better-placed than anyone to talk about the transition is ‘transgender rock revolutionary’ Jayne County. As the pre-op Wayne County, she not only hung out and performed at both Max’s, she was also resident DJ at both: “I remember how it was in the earlier days. Max’s was really like an exclusive restaurant, but with an edge that made it seem exotic and mysterious.

"It also had a lot of real freaks and gender pioneers hanging out there, not just those that were pretending, like Bowie. And there were a lot of drugs going around, too. But you couldn’t really call anyone drug dealers, more like drug givers. Everyone was on something different. And if anyone tries to tell you that Max’s wasn’t a drug den, then they are lying to cover their now-respectable asses.

“My impression began to change when Dean took over and Max’s went from being an artist hangout to a rock’n’roll hell. But, being the trashy rock’n’roller that I always was, I actually loved the change. But the more rock’n’roll it got, even more drugs got around; some nights it looked straight out of a Fellini movie.”

Whatever else was being said, under Tommy Dean the club did flourish for a time, and indeed much of the myth that surrounds the Max’s legend of today was born out of those Dean years – such as the rivalry with the now established CBGB, which threatened to turn the New York music scene into a soap opera; you were either a Max’s person or a CBs person.

By the early 80s, punk was dead and disco was taking a hold. But while CBGBs survived by embracing acts from genres such as hardcore and the burgeoning metal scene, Max’s found itself without an audience. Those that had once made Max’s great were no longer the hip young things of the New York scene, but had instead become the establishment. So yet again it was time for Max’s to meekly pull down the shutters – this time for good.

In 1982, Yvonne, by now estranged from Mickey, received a phone call: Mickey had died of an accidental overdose of Quaaludes and tequila. “He was my knight in shining armour, my hero. It took me years and years to get over it, and only now am I beginning to find closure”.

Today that closure takes the form of the charitable organisation that Yvonne runs which has brought the memory of Max’s Kansas City full circle, with the spirit of Mickey’s first love of art remembered through the Max’s Kansas City Project: “The Project was established in Mickey’s memory to honour the spirit of his philosophy of helping artists in need.”

So what does the future hold for Max’s Kansas City? Well, there has long been talk of a movie, and numerous approaches have been made to license the name for a club in Las Vegas, but Yvonne Sewall Ruskin remains cautious, and extremely protective of Max’s: “I love the idea of a private club where you have the sense of intimacy and safety that Max’s had, full of creative people mingling and table hopping, exchanging ideas and fighting over art and having meaningful conversations – and of course lots of sex… But I don’t think you could ever really have a place like Max’s today. Everything today is less about creativity and all about money”.

If it hasn’t happened already, the mythology of Max’s will eventually overtake the facts. Hopefully Max’s can retain the mystique of a wonderful memory and not an exercise in merchandising.

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 89, published in February 2006.