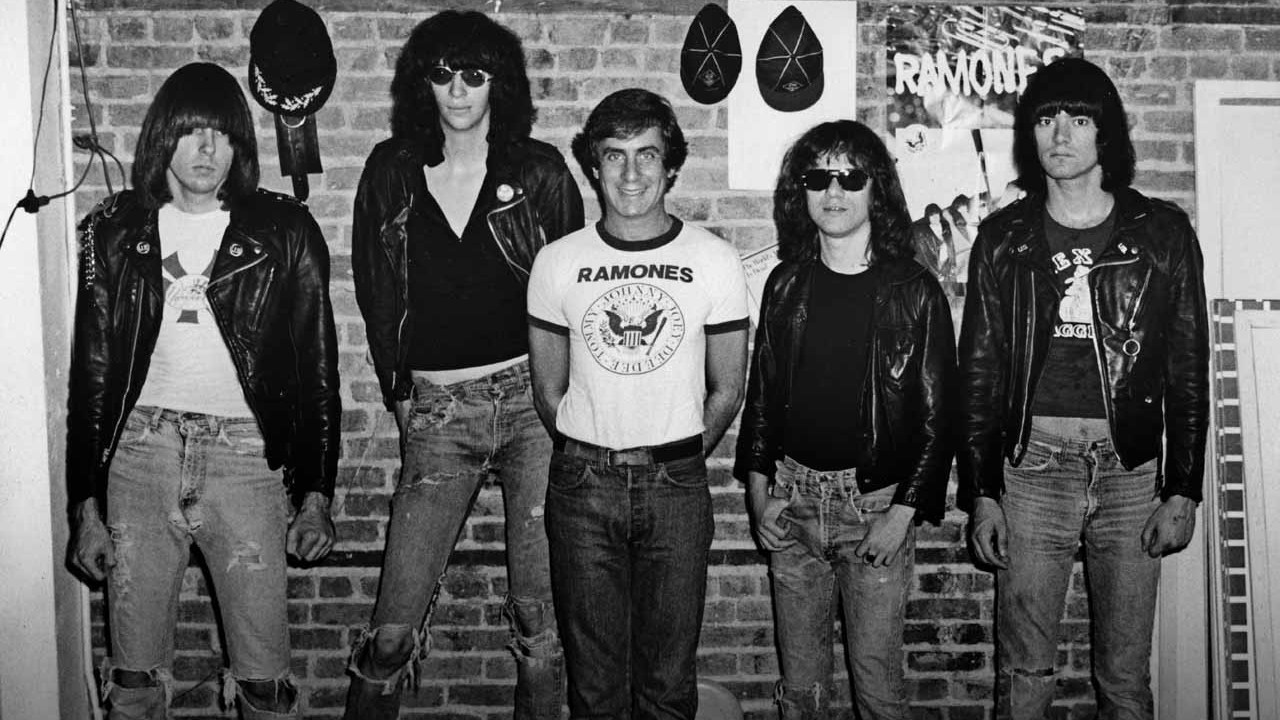

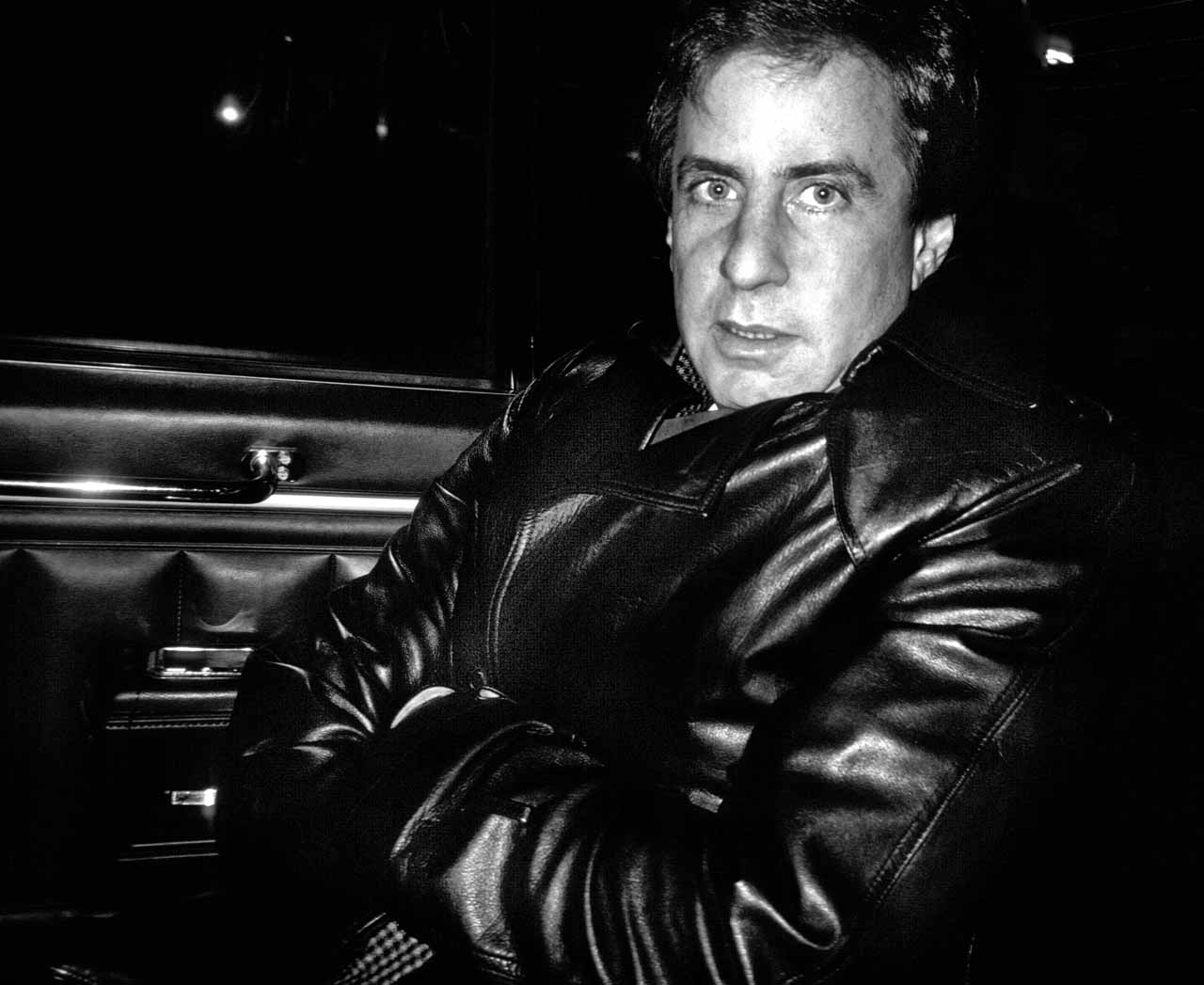

Danny Fields, now a fairly sprightly 77, was living in New York in the early 60s and became friends with Andy Warhol and the Velvet Underground. He worked with The Doors as a press officer at Elektra, signed the MC5, signed and managed Iggy Pop and the Stooges, and managed the Ramones for five years from 1975. When he brought the Ramones over to play the Roundhouse in London in ’76, they had a huge impact on the key players from the British punk scene in the audience. You could make a convincing case that without Danny Fields, punk rock might never have happened.

Was Lou Reed as hostile as he often appeared in the press?

Lou Reed was the loveliest, sweetest person I knew. We were very close in the early days. The press thought he was hostile – he always seemed to be picking fights and was arrogant. But he always said: “When people pressed the Record button, I had to become Lou Reed.” There was a lot of arrogance about that Warhol crowd: “We’re the coolest people in New York.” And we were!

Is it true that when their early drummer Angus MacLise heard the Velvet Underground had their first paying gig, he quit in protest, as he thought it was ‘selling out’?

Yeah. He said, “Fuck you.” That’s what you have to do if you’re presenting avant-garde rebellion as your trademark!

I first saw them at the Cafe Wha? in the Village and fell in love with them – the melody, the beat, the songs. Disparate, brilliant people. They just came together in this shocking, beautiful, urgent music. They hated that Californian world, and listened to Tin Pan Alley. John Cale was into avant‑garde, a brilliant musician. Lou was this insane, neurotic Jewish folk singer from Long Island. Sterling Morrison was a straight-and-narrow academic. Maureen [Tucker]… The drummer, didn’t show up one day, and someone said: “Oh, my sister’s got a drum kit, why don’t you give her a try?” I was the editor of Datebook magazine, which had this immense power, and I was the first person to run a picture of the Velvet Underground in a national magazine. Which was great, as from just being a fan I could now do something to help them.

What did you think when you saw the MC5?

I was publicist at Elektra Records and The Doors were breaking. Light My Fire was Number One and I was getting Jim Morrison into teen magazines. Elektra had Love and Paul Butterfield but it was mainly folk like Judy Collins. They were discovering a pot of gold in rock’n’roll and wanted more rock acts.

I heard about this band in Detroit who were intensely left-wing and anti-establishment, as we all were. They were the sons of Detroit auto-makers – their parents were like hillbillies who came from the south to make cars. And I saw them in Detroit’s Grande Ballroom and loved them. Three thousand people there – they already had this huge fan base. They had energy and spun around and had a lot of hair and were sexy and tough; Chuck Berry riffs and free jazz.

And they lived in a commune, and I’d never seen that before. They had beautiful posters and newsletters in vibrant colours, and their message was “tear down the walls” and “dope, rock’n’roll and fucking in the street”. Who’s gonna say no? “Let’s kick out the jams” – whatever ‘the jams’ were!

They were so disruptive, verbally and politically – the only band to play at the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago, where there were riots.

And the MC5 led you to the Stooges?

[MC5 guitarist] Wayne Kramer said afterwards: “If you like us, you’re really going to like our little brother band, the Psychedelic Stooges.”

So I went to see them, and I remember entering the hall and hearing this music like an orgasm: thrilling! You could feel the bass, the sound coming through the floor, something atavistic, something influenced by the primal forces of God and the devil. And then there was Iggy, the young, lunatic Iggy Pop. Skinny, great dancer, like nothing else I’d ever seen, an atom bomb in a lighting bolt. Their attitude was: “We don’t give a fuck – this sounds like a good riff so let’s just keep doing it.”

They once used oil drums beaten with hammers on stage. Iggy had seen Jim Morrison half-naked on stage and thought: “I’ll be bold and sexy and daring and menacing too.” Though he was far more menacing than Jim Morrison ever was. I talked to him afterwards, but he thought I was a dirty old man trying to pick him up. I rang Jac Holzman [head of Elektra] and said: “I’ve seen these two groups you should sign. The first one sold out the Grande Ballroom to a lot of rich white kids from the suburbs, and the other group are a bit far out but they’re going to be something.” He said to offer the MC5 twenty thousand dollars for a five-year contract and offer the Stooges five thousand dollars. And they both said yes.

Did you ever see Iggy on stage with his chest smeared with hamburger and peanut butter?

Oh yes! He tried to do something different each time. You felt the whole thing might end up on the front pages – there will be blood! One time he kicked these people off this heavy wooden bench in the front row and then picked it up and held it over their heads. I’ve seen him climb up pipes and curtain rods to the ceiling and perform from up there. Broken glass, chopped meat.

He threw himself onto tables full of glasses, lacerated his skin. He’s a mess now. You don’t do that for fifty years and come away unscathed. He’s done irreparable damage to his moving parts.

The phrase ‘punk rock’ hadn’t been invented then, but I liked the fact that half the people hated the Stooges and the other half were ecstatic and thought: “This is tomorrow!”

As the Stooges’ co-manager, did you ever give Iggy any advice?

“Take that needle out of your arm, come out of the john and get on stage, it’s show time.” Most junkies don’t make it out the other side. All of the original Stooges are dead except for Iggy. All four original Ramones are dead too.

- The Story Behind The Song: Blitzkrieg Bop by The Ramones

- The Top 10 Best Ramones Songs

- The TeamRock+ Singles Club

- TeamRock Radio app back on Apple’s app store

Speaking of the Ramones, what was your first impression of them?

They kept calling me. I had a weekly column in a Soho newspaper and they wanted me to write about them, as I was writing about Patti Smith and the New York Dolls. I loved them from the second I saw them. They were adorable – great hair, that guy look, a uniform but not a uniform. They realised the New York Dolls had a look and knew they had to do the same, and they briefly flirted with glam – Joey had a head-to-toe pink leather thing, and there’s pictures of Johnny in lamé pants. Then they thought, “Let’s just wear what we’re wearing – leather jackets, sneakers, ripped jeans.” They sounded overwhelming, a blast, like a nuclear-powered train coming at you, and their sets were seventeen minutes long – about ten songs. Perfect! No guitar solos.

They were funny, mad, brilliant, imaginative. They read comic books and art stories and horror, and watched movies and listened to the radio, and were brought up on the mythology of all that nonsense. We hate everybody! You’d be in the van with them and they’d go: “Look – there’s a guy with a beard. Let’s run him over!”

They were loud and swift and really smart and ambitious and their songs were perfect. We met up outside CBGB afterwards that night and they said: “Are you going to write about us?” And I said: “I want to manage you. You’re the future!” I managed them from 1975 to 1980.

The internal politics of the Ramones sounded nightmarish. Did they detest each other?

They hated each other but they loved each other. Maybe that’s what fuelled them. Joey’s girlfriend left him and married Johnny, and it got so bad they used to talk through a third person. I didn’t care if they stabbed each other as long as they made it to the show – though Dee Dee did actually have a stabber girlfriend, Connie. Dead now. She stabbed him in the ass, and tried to cut off the thumb of the bass player of the New York Dolls.

Do you remember them meeting the Clash and the Damned when they played in London in 1976, the passing of the punk rock baton?

Joe Strummer got it instantly when he saw the Ramones. He said: “You couldn’t slide a cigarette paper between the songs. Why stop and tune up? Do you think anyone’s going to know if you’re out of tune? Just keep playing! Make it like one song. The only thing that matters is, don’t fuck up the beat.” [Clash bassist] Paul Simonon was in the dressing room at the Roundhouse, and Johnny told him: “No one cares. Just go and play, do rock’n’roll like we do, cos we can’t play – we suck, we’re terrible.”

The New York Dolls couldn’t play either – terrible musicians. But it didn’t matter, cos they created a universe they owned from the moment they were in front of an audience. And here’s the ultimate irony: the Ramones were told they’d never have any hits, as radio liked two-minute-thirty-second songs, not one-minute-ten. And they didn’t have any hits, but ‘Hey, ho, let’s go!’ – that five-second snippet – is playing in some football stadium right now somewhere in the world, like We Will Rock You by Queen, and that’s how they made their fortunes. They made billions from the use of that – ker-ching! A five-second cut from one-minute-ten!

Johnny and Joey were multimillionaires when they died. Joey particularly grew up feeling ungainly, stupid, ugly, too tall, left out, beat up and thrown down the stairs at school for being six-foot-six. By the end he was like royalty – truck drivers would stop and shake his hand.

None of the bands at CBGB – Television, Ramones, Blondie, Suicide – were doing the same thing, so it wasn’t all punk rock, but in the UK there was a political dimension to it and it was all part of the punk movement. As Plato said: “When the mode of the music changes, the walls of the city shake.” And punk was a change in the mode of the music, from the Velvet Underground to the Stooges to the Ramones.

The deluxe edition of the Ramones’ second album, Leave Home, is out now via Rhino.

How the Ramones changed my life, by Nirvana producer Butch Vig