Meet Gizmodrome, Stewart Copeland's punk prog supergroup

What began as an impromptu phone call has snowballed into a punk prog supergroup with Stewart Copeland as frontman. Meet Gizmodrome – they’re “a hell of a lot of band!”

“Is it prog?” ponders Stewart Copeland, who is tall, gangly and adept at a comedy French accent. “Well, recently the French were telling us: ‘It’s progressive, but the songs are short… we are confused. We think maybe it is… punk prog!’ I’d say we’re prog because there are way too many fucking drum fills all over the place. And we’re prog because Adrian’s guitar-playing is insane and should not be allowed on a pop record. And then Mr King fires up and this is a whole new world of King – all the other bass players, like Stanley Clarke, will soil their pants when they hear this. Oh my God, that’s a hell of a lot of band. Then again, maybe it’s punk, because of the energy. And because, frankly, it’s our intention to burn down the city and eat all the children.”

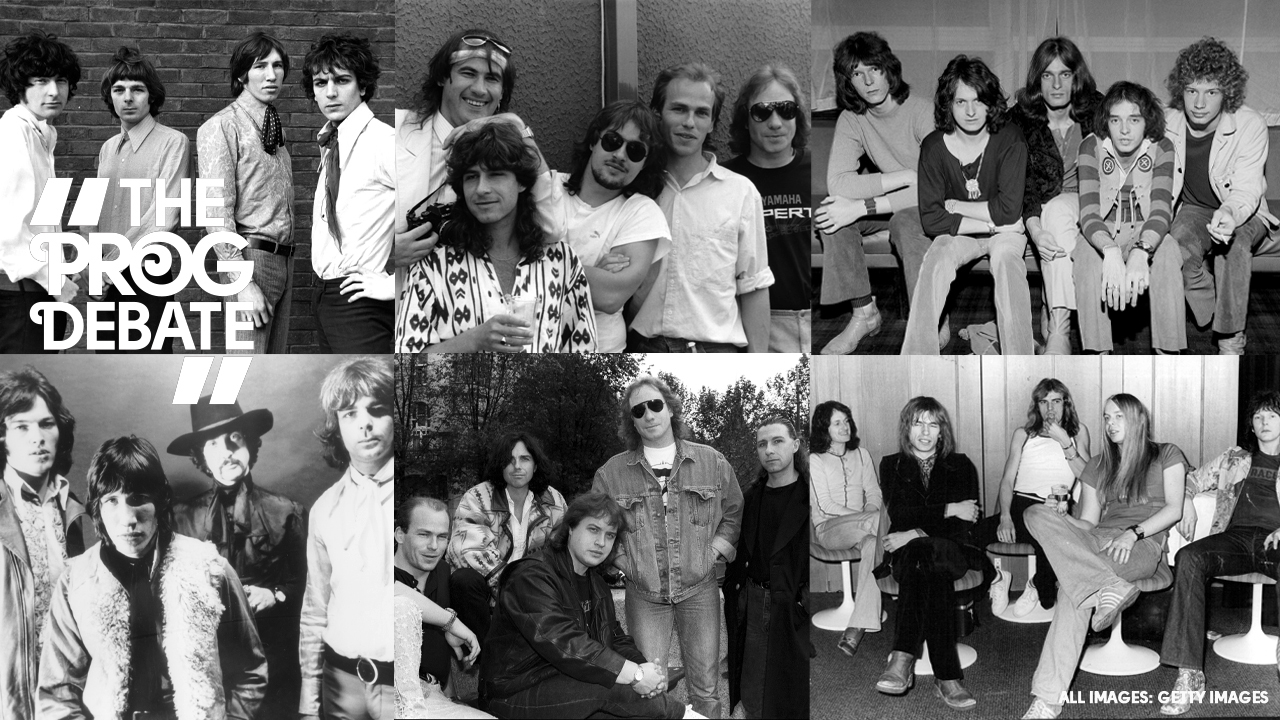

Lock up your preconceptions: Gizmodrome are here. Something of an all-star musical supergroup – “well that’s better than being called a shit group,” offers Mark King – they combine the fantasy line-up talents of Copeland on drums, King on bass and Adrian Belew on guitar, with Italian keyboardist Vittorio Cosma (a long-time Copeland collaborator) smoothing it all together. Stentorian vocals (and peculiar lyrics) are chiefly provided by Copeland in a manner he describes as “Tom Waits meets Barry White with a little hair of Lee Marvin,” while King and Belew chime in with sweeter voices. The outfit’s phenomenal pedigree coalesces in vibrant, imaginative and unexpected ways. As they eagerly confirm, there was a natural chemistry, and what’s emerged from the lab – a studio in Milan – is a fizzing fusion of prog, jazz, pop, funk, reggae and, er, fusion.

That chemistry is clear today as Copeland, King and Belew, evidently enjoying each other’s company, banter boisterously in a London hotel. Their enthusiasm, humour and sparky interplay perfectly match the eponymous album’s eclectic effervescence. So how did this crackling collaboration, this dream ticket of dexterity, come about? Although the three constantly interrupt each other with quips and teases, they’re equally fast to eulogise each other’s talents. King kicks off the tale.

“Last July, I get a text from Stew, saying, ‘Hey Marco – already with the Italian thing – do you wanna come join a band in Italy?’ Straight away I said yes. Seven days later we’re in the studio. As a bass player, the chance to play with Stewart Copeland is just fantastic. He’s got to be in every drummer’s Top 5. And I started out as a drummer, so the drums are very important to me. Then you see Adrian weave his magic, making things happen. It’s just been an absolute joy. And so easy to do – it’s not as if everyone had to find their place, to settle in… we just played, and it sounded so good that after 10 days most of the songs were in the can. Stew had most of these songs ready, but they weren’t much like they are now. We did another session in April. There’s a real sound to this band, it’s happening.”

Belew concurs. While he did add a few parts later, “90 per cent of it is us three in the studio, being able to get excited, to talk about it. Very rarely does putting people in the room together result in the synergy that this automatically had. It was palpable. By the end of the second day I was thinking, ‘Damn, what a great band this is!’ And then I’d think: ‘Oh… is it a band? Or is it a project?’ But every day we’d get up, go to the little piazza. We’d have breakfast, talk about everything in the world. Then go to the studio, play, have a little tequila at five and get straight back into it until a long late-night meal at some Italian restaurant. You do that for a couple of days, you get to know each other. The jokes and stories start to flow. You become invested in the whole thing. And you realise: this is a band! We should go and play this for the world.”

“That,” says Copeland in his best Doctor Evil voice, “was my secret plan all along. Adrian thought he was coming in to play a few solos on ‘Stewart’s project’, but by day three, it’s his project. I mean, otherwise I can’t afford these guys!”

Thus bonded, they plan to tour early next year (with Level 42’s Pete Biggin on drums to free up Copeland), hoping the response to the album will be as good as all the early signs indicate.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Copeland and King technically toured together back in 1981, when Level 42 supported The Police across Europe. King reckons it was a “fantastic education for a young dude to stand side-stage and watch how these guys, who were becoming one of the biggest bands in the world, were doing it.” He’d never met Belew before Gizmodrome, “so that in itself, if nothing else, has been brilliant.” The pair express excitement at how their voices sat together instantly. And Copeland and Belew knew each other “just marginally… by reputation…”

Butting in to their relentless rapport, I ask if, as primary songwriter, Copeland had to adopt the headmaster role.

“Ah, no, one important part of the process was we dispensed with the notion of ‘sanctity of the composer’. Of course, when you write a song, you imagine it’s perfection, it’s goddam Stairway To Heaven, y’know? But with these guys, it’s gonna get better. Whatever chords, riff, etc, I had, they’d chew on it for five minutes then for the next 25 they’d fuck it up, with my blessing and encouragement. For example, Belew comes in on something that seemed a perfectly good song and – fuck me – we’re into a whole new cosmos! Again, that was my secret trick, my plan. I wanted them to realise it was our album, not mine. That’s the way you get things happening. You get stuff out of Belew that Trent Reznor’s not gonna get; you get the real shit, coming out of his imagination. Once set free, it gets freer and freer and wilder and crazier. But this got way better than I even imagined: you can hear the excitement of real inspiration. By the way, that’s an old Police trick. Next time you hear a Police record, consider that the drummer and guitarist had never heard that song until 20 minutes before recording it. It’s a useful technique…”

King interjects, “We’d be shouting out, ‘Section change!’ And, ‘I don’t know this part yet!’ At times it was like The Troggs Tapes on acid.”

“I have to say,” muses Belew, “it struck me that for the first time in a long time, this material was custom-made for what I like to do. I bring a lifetime of experience in, and everything I’ve learned since I heard Purple Haze when I was a kid, anything you want, I can throw it in there. And if you don’t like that, fine, I got another idea. If Stewart’s singing about an alien radio station, cool, I’ll play an alien radio station sound…”

Alien radio stations are just one element of Copeland’s curious, declamatory, serio-comic lyrics, which remind one of his erstwhile punk alter ego Klark Kent. Here be zombies in the mall, horny politicians and “strange things” happening. A recurring theme is that of letting off steam, escaping, going off the rails.

“At home, I’m a suburban dad, driving my kids to school,” he says. “But when I’m out in the world, sitting at a lonely train station, riding a cab across a strange foreign city – that’s when your mind goes into really weird reveries. That’s where this shit comes from. Y’know, ‘the pain of the life that I have lived.’” Imagine, if you can, Copeland putting on a Steven Toast voice for that last part.

He goes on to discuss how mistakes are made while “looking for Babylon”, but of course what happens on the road stays on the road, even in the classical-orchestral arena he’s recently thrived in. Quoting his own lyrics, he says, “Back home you got a solid life/That don’t mean a thing out here…” The sense of rootless disorientation in his songs is, however, leavened with madcap humour. Which forces the question: what is the fascination with horses? The lyrics make frequent allusions to our equine friends.

The trio crack up, pointing at each other and declaring, “Oh, that was him!”

Finally, King shrugs, “Oh, Stew is just fucking obsessed with horses.”

Eventually Copeland moves us on. “Some things are autobiographical. I’m an old bastard coming down from my ivory tower for a fling, or at least the guy in some of the songs is. Maybe a little dinged and dented, but just give me a Cadillac and I’ll stay all night. We seem to visit many strange cities in these songs. ‘Ah, my life is a strange city,’” he all but winks.

Pressing them on whether their previous rich bodies of work inform or colour this music leads to King professing his lifelong love of jazz fusion and Belew getting mildly defensive on the subject of his King Crimson past.

“Of course when you’ve partially shared 30 years with a band of that name, some of that’s in there, but I’ve been out of that orbit for many years now. I’ve branched out solo and with my own band, so… I don’t think in those terms any more.”

Copeland clarifies that his own performance style delivery is influenced by the opera he spent three years writing. “It’s storytelling, you act the note as well.”

“He’s in character,” adds Belew. “And he’s going for it. Playfully.”

“Playful?” mock-protests Copeland. “I already told you: my intention is to burn down the city and eat all the children. It’s Darth Vader… but in a good mood. Hey, the original motivation was fun in the sun in Italy. The mission was la dolce vita. Then when these serious players came in we tried to hold onto that nihilistic feeling… and we just went ape-crazy.”

Gizmodrome is out on September 15 via earMUSIC. For more, visit www.facebook.com/gizmodrome.

Gizmodrome’s prog credentials

Stewart Copeland: The Beatmaster

Universally acclaimed as one of the greatest living drummers, Copeland’s rhythms with The Police were deceptively complex. The range of his other work is under-heralded. He played for Curved Air in the mid-70s (and was later married to Sonja Kristina for nine years). In an enduring film-scoring career he’s provided the soundtrack to such movies as Rumble Fish, Wall Street and Raining Stones, and recently he’s had success with orchestral, classical and even opera compositions. Peter Gabriel asked him to play on Red Rain and he’s performed with Mike Rutherford, Tom Waits and with Stanley Clarke in Animal Logic.

Mark King: The Shapeshifter

“My inspiration as a youngster was more the jazz-fusion stuff,” says bass boss Mark King. Starting out as a drummer (from the age of nine), it was the rhythm kings he first admired. “Those guys were so great – Billy Cobham, Lenny White, Tony Williams – those cats were just burning up. And of course that all cross-pollinates with Zappa.” Switching to bass and vocals, he launched upon years of jazz funk crossover hits with Level 42, who toured with The Police and Queen. In the 90s, Allan Holdsworth and Jakko Jakszyk joined the band, as did Gavin Harrison. King’s solo albums further showcase him as the Isle Of Wight’s answer to Stanley Clarke.

Adrian Belew: The Axe Grinder

Where to start with the in-demand Kentucky-born guitarist’s CV? Twenty-odd turbulent years as frontman with King Crimson are impressive enough, with Discipline and Beat arguably the best fruits. Prior to that came his 70s work with Zappa (who “discovered” him), his tours and contributions to Lodger with David Bowie, and his move to Talking Heads (Remain In Light) at the behest of Brian Eno. He’s at pains to emphasise his ongoing solo career, but it’d be a poor record collection that didn’t include his collaborations, whether with Paul Simon, Jean-Michel Jarre, Herbie Hancock, Laurie Anderson, Nine Inch Nails, Mike Oldfield, Porcupine Tree or even William Shatner.

Chris Roberts has written about music, films, and art for innumerable outlets. His new book The Velvet Underground is out April 4. He has also published books on Lou Reed, Elton John, the Gothic arts, Talk Talk, Kate Moss, Scarlett Johansson, Abba, Tom Jones and others. Among his interviewees over the years have been David Bowie, Iggy Pop, Patti Smith, Debbie Harry, Bryan Ferry, Al Green, Tom Waits & Lou Reed. Born in North Wales, he lives in London.