“We had The Beatles. We had the Stones. We had The Who and the Led Zep. We had The Doors, the Airplane, the Dead and Jimi Hendrix – Hendrix, for God’s sake! We had Janis and Otis and Aretha and Simon & Garfunkel and Cream and Van Morrison – an incredible period of time. And when you’re in it, you start to think ‘this is the way it’s always going to be!’”

Most people’s definition of being “in it” might extend to the buying of a few albums, the wearing of beads, the smoking of dope and the trooping along to some late-Sixties concerts on the West Coast in sun-baked pleasuredomes such as San Francisco – magically described at the time by Jefferson Airplane’s Paul Kantner as “forty-nine square miles surrounded by reality”. But “in it” for Richard Loren meant the deep end.

His charged and amusing memoir High Notes records a few key incidents. He starts out as a booking agent and talent-scout in ‘66 and earns extra respect by carrying one of the Airplane’s bags across the Canadian border (he’d agreed before he’d inspected its weed-stuffed interior). Elektra president Jac Holzman then invites him to get involved in the hands-on management of The Doors: he carts Jim Morrison back to the hotel after a New York show where Jim “stumbled into his room, pissed in the wastepaper basket and fell on top of the bed, snoring loudly”. Andy Warhol takes a physical shine to “the Bad-Boy Baudelaire Of Rock” at a party and presents Jim with a preposterous gift, an ornate antique French plastic telephone with a rotary dial. “It’s just what I always wanted!” trills the good-natured Morrison. It’s Richard’s job to comfort the uncontrollable singer when he’s maced by panicked security guards at a sports arena in New Haven who mistake him for a member of the lively audience. Morrison is blinded for half an hour and, for once, understandably angry.

And so the rock world evolves, “a swirl of mini-skirted and bell-bottomed entertainment movers and shakers sipping cocktails” with Loren a few steps to the right of its molten core. At one party he finds Lauren Bacall, Jason Robards and Bobby Kennedy watching Woody Allen sitting cross-legged on the carpet doing card tricks. It was a explosive time, not least because the collision between the old and new worlds was so extreme. Rock bands were way more outrageous than they are in the 21st Century and the outraged outside world was far more conservative. He watches an Airplane show where Grace Slick strips to the waist in the rain as she doesn’t want to get her blouse wet.

“Grace was from a wealthy family,” he points out. “She was educated in private schools and rubbed shoulders – and other body parts – with the upper crust. So she was rebelling against the attitudes and values that she’d come to despise. She was a proto-feminist who demanded the right to express her views. Which tended to be raw and spontaneous. Especially when fuelled by alcohol. She didn’t like the rich and powerful who controlled her and she was fearless with a microphone in her hand.”

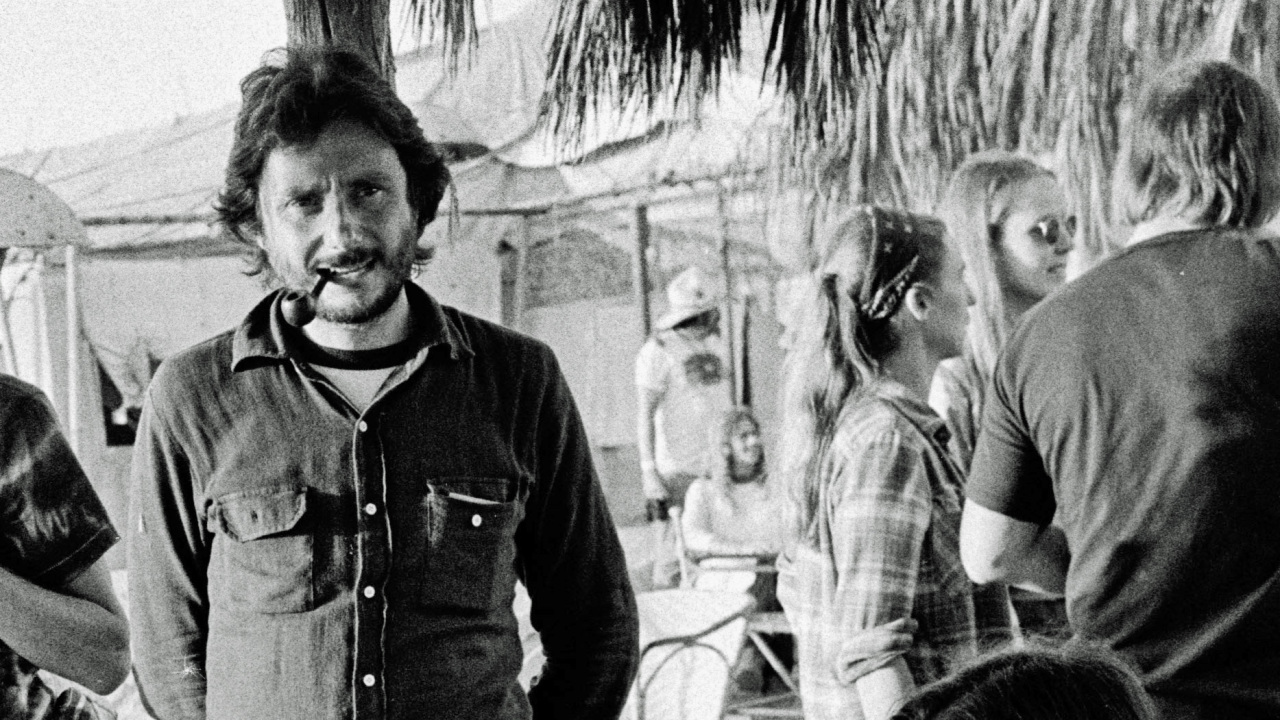

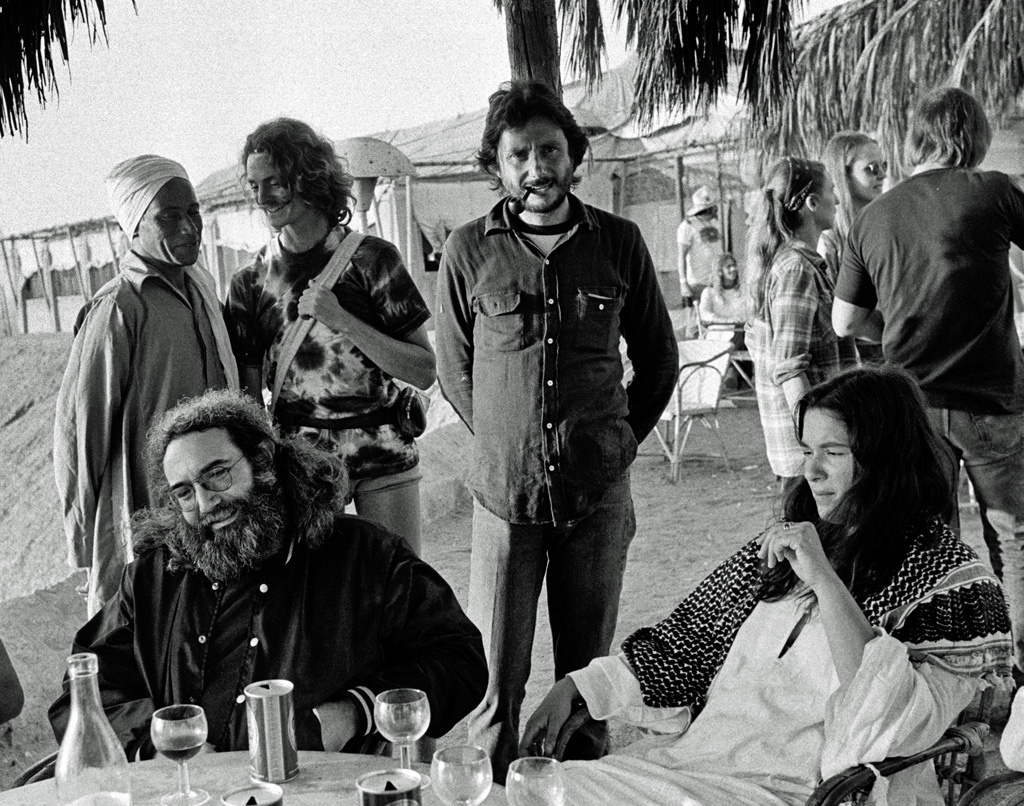

Exhausted by touring and wary of money-grabbing industry sharks, the Grateful Dead invite Richard to be their business manager in 1974 and a fascinating new episode begins. Loren is the right guy for the job: he’s up for the odd tab of acid and can smoke a bale of weed with the best of them but he’s still sufficiently grounded to run their tangled finances. The band are rambling and spontaneous in every sense imaginable, utterly in a world of their own. As Fillmore promoter Bill Graham puts it: “The Grateful Dead aren’t the best at what they do; they are the only ones who do what they do.”

On holiday in Egypt in ’75, Richard travels to Giza and notices there’s a huge wooden platform near the base of the Great Pyramid. A light-bulb turns on in his head.

“Most groups have a few hits and then play those hits night after night after night but the Dead played different sets each time, an interplay, one song free-flowing into another, you didn’t know what would happen next. The music always changed magically wherever they went. And there I was on this camel looking at that stage beneath a necklace of stars and a pendant moon - and hanging out with all these Arabs and Egyptians who all got high on hash – and thinking ‘the Dead could play here!’”

And in 1978 of course they did, the last of their three shows coinciding with a lunar eclipse. It says something about their still-chaotic operation that they hadn’t bothered to take the guy who tuned the band’s piano with them and it was so off-key they refused to release any of the footage they’d shot, eventually clawing back some of its ruinous cost by touring the States playing their Giza set with a slideshow of photos behind them. Some of the Dead were hard to handle – not least co-drummer Bill Kreutzmann who pinned him to a wall on more than one occasion – but Loren has nothing but love for the late Jerry Garcia, the world’s least showy guitarist and the band’s main creative engine.

“He was wise and caring, a rock and roll Buddha. He made everyone he encountered feel they were his friend. He wasn’t a pompous rock star with a big ego – in fact he was the ‘Non-Leader’ of the Grateful Dead - yet he so charismatic and enthusiastic. There’s no way to measure his greatness and magnitude as a person.”

Looking back now at the age of 72, what does he think were the best and worst aspects of the Sixties?

“Well the worst was they were troubled times. We talk about it being a Summer Of Love but a few years before that John Kennedy had urged Americans to build bomb-shelters as the Russians had missiles in Cuba pointing at the United States. And then all of a sudden - boom! - our ‘Camelot’ President was shot. It was a trauma!

“But the best thing was the introduction of marijuana, especially to musicians. We were young and idealistic and thought it’s all going to be love and compassion and all that stuff, but what killed everything was the Eighties. When Reagan became President and said ‘yes’ to greed and the hippies were replaced by yuppies, ‘the more money you make, the better you are’ and the indifference to the suffering of the poor and underprivileged became like a positive virtue. It was all about chasing the Mighty Buck – and look where that’s taken us today, the complete corporatisation of the music industry.

“We were living the dream,” he says. “We really thought the world was going to change. We didn’t realise the boot-heel of authority was going to come slamming down on our throats again.

“We were young. We were fools. But we were happy!”

High Notes by Richard Loren is out in paperback from East End Publishing.