As Smashing Pumpkins were approaching recording sessions for their third album in 1995, Billy Corgan told his bandmates to treat it as if it would be their last. The frontman believed that life worked in seven-year cycles and, with his band’s seventh anniversary approaching, he felt it in his bones that something was coming to an end. “It will either be our last album, or it will be our last album as people know the Smashing Pumpkins,” he remarked.

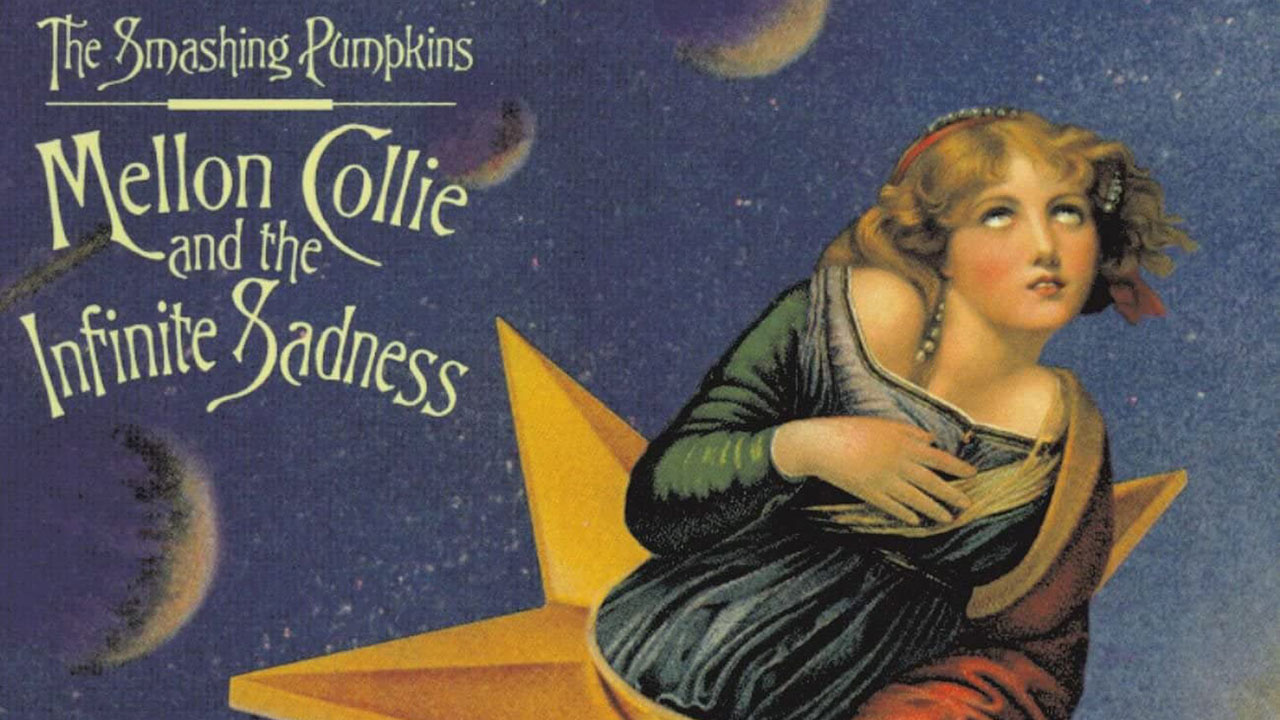

Even Corgan must have been surprised at how on the money his premonitions were. Mellon Collie And The Infinite Sadness, released 25 years ago this week, didn’t just signal the end of the road for the Pumpkins’ classic line-up of Corgan, guitarist James Iha, bassist D’Arcy Wretsky and drummer Jimmy Chamberlin, it was the full-stop on what had been a purple patch for US rock albums. Mellon Collie was the final instalment of a run of era-defining records that were released during the first half of the ‘90s. It was as if its very scope and ambition made everyone else go, “well, what now?”.

The truth is that by the time the Chicagoans turned their attention to Mellon Collie, their peers had already started to beat a retreat from the limelight, burnt by the glare of mainstream exposure. Siamese Dream, the Pumpkins’ second album, had itself sold a whopping three million copies, but Corgan wanted more and arrived home from the band’s headlining Lollapalooza tour in 1994 with a fire in his belly. He took three days off and then started writing five hours a day, six days a week. Whereas Kurt Cobain and Eddie Vedder’s punk sensibilities had been offended by huge sales and chart success, Corgan had no such shackles. A fan of Rainbow, Cheap Trick and Queen, he took it as a dare to dream even bigger and envisioned a double album in the vein of The Beatles’ White Album. The band’s label, however, did not take this news particularly well, telling the singer that double albums did not sell. Corgan stuck to his guns.

That’s not to say that Corgan re-invoked the dogmatic style that had seen him play most of the guitar and bass parts on Siamese Dream. Instead, there was a loosening of the reins and much of Mellon Collie’s dynamic explosiveness came from that sense of a band who reached new levels playing in a room together. It was producer Flood’s insistence that the band record the base of Mellon Collie’s songs in their Pumpkinland rehearsal space to capture the exhilaration of their live performances. With those laid down, they re-located with Flood and co-producer Alan Moulder to the Chicago Recording Company studio to add the sonic flourishes and embellishments.

The resultant album was Smashing Pumpkins’ masterpiece. A double-disc made up of 28 songs, it swerved gracefully from symphonic rock to barbed-wire riffs to electronic art-pop to acoustic balladry and back again and then finished with a song that sounded like the sort of thing you might hear during CBeebies bedtime hour. Has there been a rock record with so many different sorts of songs that were hits too? On the face of it, Corgan’s drawl is the only thing connecting Bullet With Butterfly Wings, 1979 and Tonight Tonight but, somehow, they all sound like Smashing Pumpkins. Mellon Collie was Billy Corgan’s grand artistic statement, a record that reflected the mercurial genius of the Pumpkins leader. He knew it too. “We’ve talked about it as a band,” Corgan said soon after the record’s completion. “It’s a pretty amazing war horse, a great accomplishment.”

The concern that doubles didn’t sell lingered, however, with Corgan saying he’d rather split up the group than have an epic folly hanging over them for the rest of their career. He needn’t have worried. Mellon Collie went to Number 1 on the Billboard 200 and went on to sell over 10 million copies. Viewed through a long lens, it’s the touchstone for any band looking to push the boundaries of their sound and its influence can be heard on records by Muse, Biffy Clyro, My Chemical Romance and more. It has cast a shadow beyond guitar music, too – earlier this year electronic don Four Tet cited it as an influenced on his tenth record Sixteen Oceans.

It could never be replicated, however – not even by the Pumpkins themselves. A year into the accompanying tour, Jimmy Chamberlin was fired from the band after overdosing in New York with touring keyboardist Jonathan Melvoin, who died. The band’s magical alchemy may have been broken but their legacy was assured. “We finally managed to manifest everything I always thought we could do,” Corgan recollected. “Somehow we managed to get a lot of blood out of the stone.”

Mellon Collie And The Infinite Sadness may have been the end of an era, but Smashing Pumpkins had captured lightning in a bottle. A quarter of a century on, its brilliance endures.