‘I’m goin’ to Memphis, where the beat is tough,’ Jerry Lee Lewis once sang. ‘It makes you tremble and it makes you weak /Gets in your blood…’

America took its very rhythm from Memphis: birthplace of rock’n’roll, hotbed of blues and gospel, crucible of southern soul and once home to Sun, Stax, Hi and American Sound Studio. Yet one strain of music, white-boy rock, seemed curiously absent from this busy corner of Tennessee, at least until the early 70s. Enter Big Star.

Their songs sounded like guitar-driven paeans to adolescence, bursting with rich melodies and radiant harmonies. But beneath the surface was a complex world of turmoil and uncertainty, one whose narrative unfolded across three markedly different albums. By the end of the 70s Big Star were all but forgotten. One of them was dead and the others had drifted apart in various states of disenchantment.

It might have ended right there, had the band not been rediscovered by a generation of bands in the 80s and 90s. The Replacements, Primal Scream and Counting Crows are just some of thosewho acknowledged a major debt. As R.E.M.’s Peter Buck, another key admirer, once put it: “Big Star served as a Rosetta Stone for a whole generation of musicians.”

“People were discovering the band when there was no real profile for us,” says drummer Jody Stephens, Big Star’s last surviving member. “We became like a secret handshake. If you knew who we were, then you were more than just a casual listener.”

The progeny of mostly well-to-do families around Memphis, Big Star emerged from local band Icewater in 1971. Stephens, bassist Andy Hummel and singer/guitarist Chris Bell were soon joined by another guitar-toting vocalist, Alex Chilton. The latter was already arelative veteran at 20, having been frontman with the Box Tops, who scored a US No.1 in 1967 with The Letter.

Chilton may have been the original blue-eyed soul boy, but it was music from further afield that galvanised Big Star into being. “We were all huge fans of the British Invasion,” says Stephens. “Then the next wave that had the same sort of impact was Stax Records, with Otis Redding and those folks. But we never really talked about a sound. Chris and Alex would bring songs to rehearsal and it all just came naturally.”

Crucially, the band were given free reign to experiment at nearby Ardent Studios, under the tutelage of owner John Fry. As an engineer/producer for Stax, of which Ardent was a subsidiary, Fry knew his way around a recording console. It was an experience that fed into Big Star’s 1972 debut album, #1 Record.

With Fry at the helm, layered harmonies and post-Byrds guitars were underpinned by white-soul beats that allowed a little grain into the groove. “John was our fifth member,” says Stephens. “Without him Big Star would never have happened. Chris and Andy would spend hours in the studio, playing around with guitar parts and vocals. There’s something about the high end that always found its way on to our recordings.”

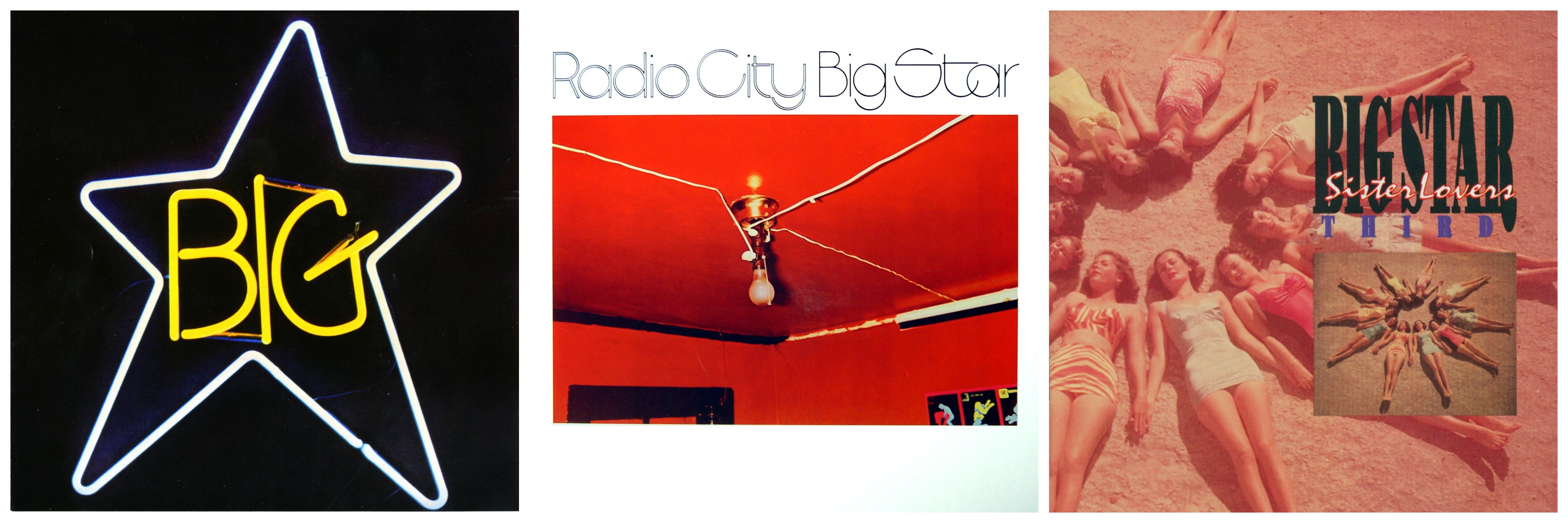

With Chilton and Bell sharing the songwriting, #1 Record was heavy with yearning pop songs of heartache and hope. Standouts such as The Ballad Of El Goodo, Thirteen and Try Again were precariously balanced between elation and despair.

“Big Star are so effortlessly listenable, but what makes them interesting are the nuances and subtleties,” says Drew DeNicola, director of recent documentary Big Star: Nothing Can Hurt Me. “They were one of the first revisionist rock bands in that they were recapturing the elements of their favourite music of the sixties, putting them through this Memphis blender and then back out.”

Alas, the problems began when #1 Record was released. Despite rave reviews, Stax couldn’t work out how to market an album that made precious few concessions to glam, prog or any other prevailing trends. As a result of shoddy distribution, it sold less than 10,000 copies.

Of even more concern was Chris Bell. His volatile partnership with Chilton came to a head when reviewers singled out the latter as Big Star’s chief figure. The band tentatively started work on a follow-up at the end of 1972, but Bell’s resentful behaviour became ever more erratic, picking physical fights with the others and finally leaving the group. He was, for a time, admitted to the psychiatric wing of a local hospital.

“Alex had sung The Letter when he was sixteen, so it made perfect sense for music journalists to spotlight him,” reasons Stephens, “even though #1 Record was really Chris’s vision. Obviously Alex was a huge part of it too, but if you had to name a producer it was Chris.”

The band split for several months, before deciding to press on as a trio. By the time Big Star re-entered Ardent the following autumn, they’d received a boost by playing to an appreciative throng of industry insiders at the Rock Writers Convention in Memphis. Their resulting second album, Radio City, issued in February 1974, was slightly looser and less meticulous than its predecessor. By then the band were partying nightly amid the sybaritic demi-monde of bars and clubs on Overton Square, two blocks from the studio.

“Midtown Memphis was the centre of the universe for certain hedonistic activities,” Stephens recalls. “People would go over to Overton Square, have a good time then come back to Ardent to record. Sometimes alcohol and whatever else you’ve been taking enhances some sort of introspective pondering. I think Radio City has that kind of thing.”

Bell’s presence could still be heard on O My Soul and Back Of My Car, two songs he helped originate but for which he didn’t receive a credit. But Chilton emphatically stamps his singular imprint on What’s Going Ahn (co-written with Hummel) and the frankly stupendous September Gurls. But for all its exuberance, Radio City is freighted with a sour kind of acceptance. It’s as if the band knew they were destined to fail.

“Alex is singing things like: ‘I can’t get a licence to drive in my car/But I don’t really need it if I’m a big star’, where he’s making fun of the fact they’re not successful. Alot ofhis themes were the loss of dreams,” says Drew DeNicola. “The same thing that you hear in Roy Orbison and the Everly Brothers and old-time rock’n’roll.”

The dream was indeed pretty much over. Despite glowing reviews, Radio City didn’t sell a lot more than #1 Record. Stax’s distribution deal with Columbia had hit financial trouble. When the label went bankrupt, Ardent was cast adrift, leaving thousands of albums languishing in the warehouse. It was a tipping point for Hummel, who duly quit.

Dispirited, Chilton and Stephens stumbled on and began recording athird Big Star album later that year. Legendary Memphis player Jim Dickinson was brought in to produce, but the sessions, augmented by arevolving cast of musicians, dragged on and on. Chilton had got deeper into drugs and booze, and the new songs sounded like the work of a man who was slowly unravelling. He seemed intent on deconstructing his own compositions, creating doleful, experimental numbers with intermittent flashes of white noise and pop genius.

Ardent eventually called time. A test pressing was made, but money issues combined with the nature of the material meant the album was shelved. When it was finally picked up by PVC Records in 1978 they released it as Third/Sister Lovers. It was as desolate as it was beautiful, a concerted outrush of self. Chilton pressed his DNA into songs such as Holocaust and Kangaroo. “It’s pretty wild music,” he said at the time. “It’s a great hash of demonic sound.”

“The whole Big Star story is in those three albums,” Stephens says. “There’s innocence to the first one, then things evolve into more worldliness and sophistication – and edge – on Radio City. And we get to the third album and there’s this amazingly painful beauty there. It’s a revelation of where Alex was at that time in his life. He was a free spirit when he stepped up to the mic or wrote a song. It’s an incredibly honest record.”

Predictably, Third/Sisters didn’t sell either. By the end of 1978 Big Star really were finished. So, tragically, was Chris Bell. Just after Christmas, the car he was driving veered off the road and hit alamp post. He died instantly, aged just 27.

Post-Big Star, Chilton moved to New York, where he briefly formed Alex Chilton And The Cossacks and produced The Cramps. There was a scrappy solo album, Like Flies On Sherbert, before he hooked up with countrybilly outfit Tav Falco’s Panther Burns. He shunned his past life, turning his back on Big Star to an almost self-destructive level.

Drew DeNicola remembers seeing Chilton in New Orleans, where Chilton settled during the 80s, playing cover versions of Volare, wearing a lounge suit and velvet jacket. “Nothing made sense with Big Star to me at the time,” he recalls. “But Alex had a problem with reality. He’d been a star with the Box Tops while he was at school. He was dropping acid with the Beach Boys and getting laid by groupies at sixteen.”

In the meantime, a bunch of US post-punk bands were in thrall to his legend. Chief among them were The Replacements, whose leader Paul Westerberg revealed in his 1987 song Alex Chilton: ‘I never travel far without a little Big Star.’ His subject repaid the compliment by playing guitar on The Replacements’ Can’t Hardly Wait.

“They really were the inadvertent godfathers of the independent music scene,” says DeNicola. “Their music had elements of rock, but it also had this emotional pull that made you listen over and over again. They had a real power and complexity.”

In 1993, Stephens took a call from the University of Missouri, asking if he’d consider playing some Big Star songs on stage with his old bandmate. Surprisingly, Chilton also agreed. The line-up was fleshed out by Jon Auer and Ken Stringfellow from Big Star devotees The Posies. Chilton enjoyed himself so much that Big Star carried on into the next decade. A new studio album, In Space, was released in 2005.

Sadly the band’s Indian Summer lasted only until March 2010, when Chilton suffered a fatal heart attack on the eve of the South By Southwest festival. The remaining members arranged a tribute gig at the festival, for which they were joined by original guitarist Andy Hummel (who himself died of cancer less than four months later).

“I guess Big Star had a lot of unfinished business and they weren’t completely coherent when Alex moved away and Jody moved on,” says Stringfellow, trying to explain Chilton’s about-face in the 90s. “By virtue of the fact that Big Star didn’t succeed, Alex presented this dichotomy where the good stuff suddenly wasn’t part of the commercial landscape. So in a sense, just by being this great band that didn’t make it, Big Star became symbolic of that ideal: the less fans you have, the better your band is. Nowadays that’s the new harbinger of quality. After all this time, I think Big Star have come full circle.”

“Their music’s familiar, but it’s twisted.”

Film-maker Drew DeNicola on his labour-of-love Big Star documentary

Drawn to Big Star’s music as a teenager, US filmmaker Drew DeNicola reached deep into their myth for recent documentary Big Star: Nothing Can Hurt Me. “They influenced so many people, but a lot of what they did was created in a vacuum,” he tells Classic Rock. “I wanted to show that what they were doing was truly unique. Usually with avant-garde or underground bands, their music has a heavy dissonance to it - elements that turn the general population off - but Big Star are so effortlessly listenable. It was interesting that what made them not ready for primetime were the nuances and subtleties of that band. The music’s familiar, but it’s twisted. ”

Aside from highlighting their glorious, guitar-led epiphanies of elation and despair, the film also fleshes out the often complex inner lives of the various band members. Its central figures are songwriters Chris Bell and Alex Chilton, whose flammable relationship gave Big Star’s music so much of its delicious tension. Bell was dead at 27. Chilton suffered a fatal heart attack in 2010, four months before bassist Andy Hummel succumbed to cancer.

“Various people had passed away and I started to realise there was an intrigue in talking around the members,” DeNicola says of the documentary process. “There was a sort of mystery there and I wanted to engage with the fact that we were telling the story of ghosts. All this stuff - Chris’s passing, the band’s failure and some of the enmity with Alex after he left - was still very palpable. Those people around the band at Ardent Studios are feeling that still, and that was shocking to me. People would get teary-eyed if you mentioned Chris Bell. It was as if they knew that they’d lived through something special.”

Big Star: Nothing Can Hurt Me also presents a kind of socio-musical study of the band and its place in Memphis lore. “In the ‘70s it was a very happening recording town, with three really big studios. The crew that we met were very nostalgic about that time, because they were living like kings. That was part of the story that I was trying to get across, that Big Star were disillusioned in a way because they lived like rock stars in a town where reality wasn’t figuring in so heavily. They had total access to one of the greatest studios in the South, they drove sports cars, they didn’t need any money, they could get into every bar and had tons of women around. It was a really wild scene, because Memphis was a party town for the entire Delta region. So they had this totally weird illusion about themselves and their life. And also a sort of disinterest in New York City or LA, because they thought they already had it all there in Memphis. T.G.I. Friday’s was where the Memphis bohemian elite went to party, get loose, listen to old records and do a bunch of Quaaludes. It was like Big Star’s version of Max’s Kansas City.”