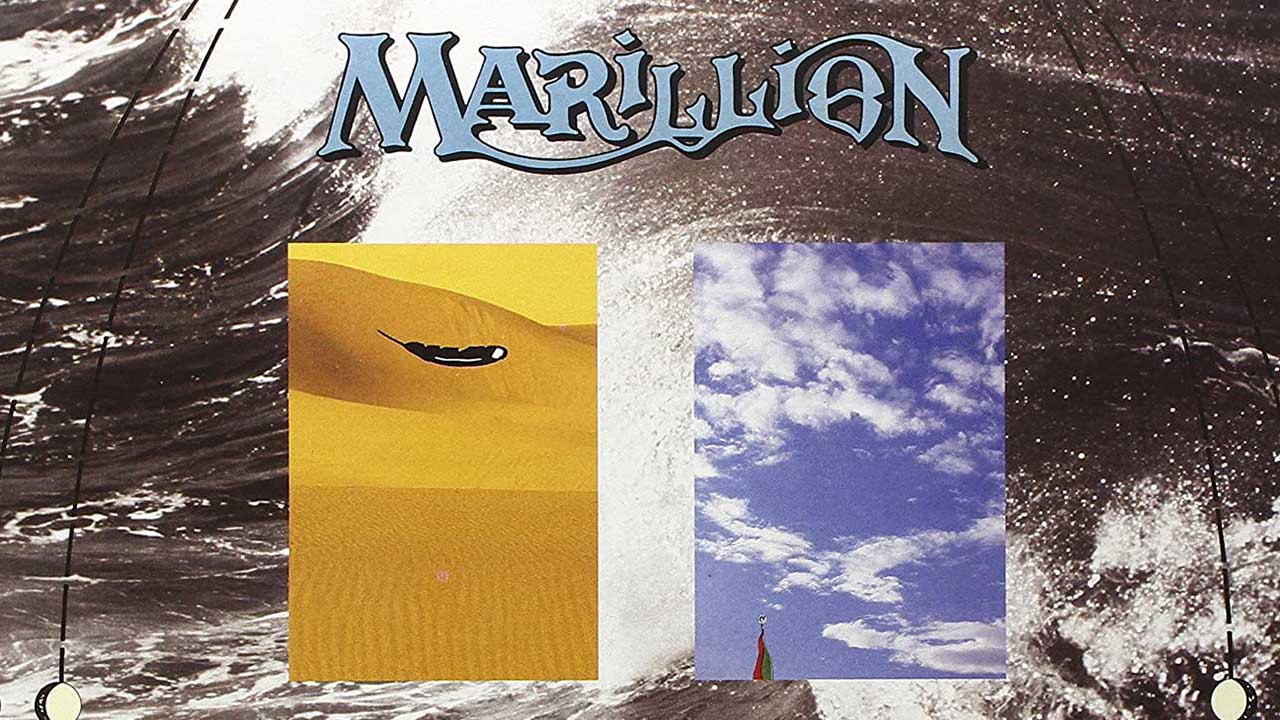

Men for all seasons: The inside story of Marillion's Season's End

When Marillion’s charismatic frontman Fish quit in 1988, many people expected the band to evaporate. But instead they delivered one of their finest records

"I was sat by the pool one say at Hook End Studios, and these two coppers and a couple of blokes in suits came walking across the lawn. It was a lovely sunny day and I’m sat there with a Pimm’s, by the swimming pool. They came up and ran through a list of names of the guys in the band, and I’m like: ‘Nah, none of them are here, mate, it’s just me. Is my name on that list?’ And they said no.

"So I told them they needed the others and I’d round them up. I asked them if they’d like a cocktail, and I got them a jug of Pimm’s. They’d come to serve us a writ from Fish to stop us recording.

"We videoed it; asked them to get the handcuffs and truncheon out. It was a scream. Legally he couldn’t stop me recording, just the band, so I just went in and did vocals for a couple of days while we overturned the writ. So it didn’t really make any difference.”

It’s early April 2004 and Steve Hogarth is sitting in Marillion’s Racket Club studio complex in deepest Buckinghamshire, relating the above tale about how the band’s gargantuan ex-frontman tried to throw a spanner in any forthcoming Marillion activities following his departure from the band in 1988.

In three weeks’ time from now Marillion will once more find themselves in the UK Top 10, with their new single You’re Gone, from their excellent new album Marbles. The new record is testament to how the band have adapted to not being signed to a record company and instead running everything themselves. But today’s conversation does not revolve around their latest album, but rather delves back 15 years, to the days when a fresh-faced ex-member of The Europeans by the name of Steve Hogarth first made the acquaintance of a band called Marillion.

Although, fittingly, the last time a Marillion single made the UK Top 10 had been from the band’s album that preceded that meeting, when in May 1987 Incommunicado, from Clutching At Straws, reached No.6. Clutching At Straws was Fish’s final visit to the recording studio with Marillion.

Despite everything appearing hunky dory from the outside (they were pretty successful to boot; Clutching… entered the UK album chart at No.2 and sold more than a million copies) all was clearly not well in the band. Within the year, what had a just few years previously been deemed unthinkable had happened: Fish had left Marillion.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“He delivered an ultimatum to the band about what he wanted with regards to money and control, and threatened to leave if he didn’t get it,” guitarist Steve Rothery explains. “And we said goodbye, really.

“Then we had all the legal problems, because although he’d left the band he was still a director of the company. It all got very messy and very expensive, and it was all kicking off during the making of Season’s End [Hogarth’s first album with Marillion]; that’s when we had lawyers turning up with writs.”

Rothery and bassist Pete Trewavas – seated next to Hogarth on a sumptuous black leather sofa – both smile and make a mock show of despair when Fish’s name crops up. It seems that even today not an interview passes without his name appearing like a bad smell. Later Hogarth will go further, and admit that until recently the whole Fish thing had really got under his skin. But today we’re talking about Season’s End, so there’s no door open for the big man.

“It was the strange situation of being very successful and also having a horrible time in our lives,” Trewavas continues on the lead-up to Fish’s departure. “It was a complete nightmare, and I don’t think any of us would want that much success again. It was so destructive.”

“We weren’t given a break, we were just put on tour by our management,” Rothery adds. “People were unhappy for various reasons, and touring became incredibly frustrating. You’d be playing to fifteen thousand people in Paris and it just wasn’t fun.

“We did the Clutching At Straws, tour then we went off and tried to write, but there was a lot of friction there; Fish no longer seemed to like what we were doing musically. It wasn’t happening. And we did this last-ditch thing up in Scotland. Nobody thought it was going to work, really. And then it all kicked off. We had a publishing deal worth a million pounds on the table we could have signed if we’d wanted to. But it wasn’t going to carry on. We were writing in one room, and Fish was somewhere else.”

So there they were, a very successful UK rock band, holding the flag aloft for their unique brand of atmospheric prog against the ‘hair attack’ of Bon Jovi and the grittier, darker noise of the likes of Metallica, and suddenly their main focal point and media-friendly frontman legs it. One would have thought a band finding themselves in that position would… well, shit themselves.

“Not at all,” Trewavas insists.

“We never doubted that we could carry on,” Rothery adds. “It was a little time before we found Steve. We auditioned so many people, none of whom were anywhere near what we were looking for. But we were writing music all this time. If we’d have gone six months without finding anybody then maybe the doubt would have set in, but we really did believe that we had something very special.”

It seems that some sort of sense of inner peace pervaded the entire period of what most would assume was an intensely worrying time for Marillion. Even the process of replacing such a domineering front figure seems to have been handled in a relaxed manner. And yet Fish was, rightly or wrongly, deemed to effectively have been Marillion throughout the majority of the 1980s.

“We wanted to find somebody with whom we had great chemistry; somebody who was very, very different from Fish. We didn’t want a Fish clone,” Rothery insists. “Fish was a very hard act to follow. He was a charismatic frontman and a great lyricist, and we knew it would be very hard to replace him.”

“It was quite obvious when we started auditioning people what they thought we wanted,” Trewavas adds. “And none of them fitted the bill. We did have some quite hysterical moments with people prancing around with make-up on. It wasn’t a case of knowing what we wanted, but of knowing what we didn’t want. And we sifted through all that, and eventually, months and months later, Steve turned up. And he was about the only decent thing we’d heard.”

So enter Steve Hogarth, previously the frontman with dark, Peter Gabriel-esque pop band The Europeans, and more recently with the more melodic How We Live. But auditioning for Marillion doesn’t seem to have been a priority at the time.

“Absolutely not,” Hogarth says now. “ How We Live had just split. They’d wrung every last bit of self-esteem and confidence out of me, and I didn’t want to be a musician any more. I was in the process of jacking it all in, selling our little house in Windsor. We were going to move to Derbyshire, where back then you could buy some place for virtually nothing, and get a no-brain job like a milkman and live a quiet life and get real again. I’d been working with my head for so long I just couldn’t cope with it any more.

“I was in the process of this, just before Christmas 1988, and I was in the office of Rondor, my publishers, and asked if anyone had anything I could do – I meant in the office, a bit of typing, or engineering their little demo studio; just basically to be able to relax and enjoy it and not be under any pressure. Being Christmas, everyone was hung over from a party. The general manager, Alan Jones, lifted his head up off a sofa in his office and said: ‘Do you know Marillion are looking for a singer?’ I said: ‘I didn’t mean that’.

“He badgered me into sending them a tape. It really was like that. I didn’t even know he’d sent a tape. I think he did it a few days later when he’d sobered up.”

That demo tape included an early version of Easter, Games In Germany and The Europeans’ Til Kingdom Come (although not How We Live’s 1987 track Dry Land, which Marillion would go on to make their own on 1991’s Holidays In Eden).

“I had a drinking mate in Windsor called Daryl Way, who’d been in Curved Air, and he’d had this band called Daryl Way’s Wolf with [Marillion drummer] Ian Mosley drumming for them,” Hogarth continues. “I told him about Marillion and he said I should check them out. So I started thinking about it a bit more.

“We’d just got back down from looking around Derby, in January 1999, and a bloke from Marillion’s offices phoned. That’s how it happened.”

If Marillion weren’t looking for a Fish clone, then they couldn’t have found someone who fitted the bill any better than Hogarth. In Fish you had a large and larger-than-life figure who exuded bar-friendly bonhomie. One of the guys, Fish was a man who wore his heart on his sleeve, possibly in the hope that his angst fuelled soul-bearing would find favour with Marillion’s fair share of female fans.

The smaller Hogarth brought with him a slightly darker air of mystery, as well as a very different and distinctive voice. There was always the impression that the band’s female fans would jump at the chance of mothering the man.

“The first meeting was round at my house,” Trewavas recalls. “I have two cats, and Steve’s allergic to them. He was a day late, too, and we had to stand outside in the cold as it was January. But we just liked Steve’s voice and him as a person.”

“We had all the gear set up in Pete’s garage, and some lyrics, and we just started jamming around a bit,” Rothery explains. And how was this meeting for the new man?

“They gave me a sheet of words and said: ‘We’ll play this idea we’ve been jamming around, and do you want to sing these words?’” Hogarth laughs. “There wasn’t a tune, they just told me to make one up. So I took a deep breath, listened to what they were doing and did it. They went: ‘That’s great.’ But it sounded like hell to me. That was King Of Sunset Town. We’d almost written it within ten minutes of meeting! A lot of the songs came together very quickly.”

The first meeting was round at my house. I have two cats, and Steve’s allergic to them. He was a day late, too, and we had to stand outside in the cold

Pete Trewavas

It soon became apparent to all parties that Marillion had found their man. “We thought it sounded like it was working, he seemed like a nice bloke and we’d done some homework – we knew The Europeans and How We Live,” Trewavas says. “We thought what we should do next is have a couple of weeks away together and work on some stuff.”

“I felt the same about that,” Hogarth concurs. “I didn’t want to say: ‘Yeah, I’ll join your band.’ Being in a band is more than just making music, it’s living in each other’s pockets and being able to cope with the individual characters.

“I’d coped with that already in the past; one bass player I worked with turned out to be a psychopath and nearly killed me. Once that’s happened you don’t just go diving in. So we went away to this residential rehearsal studio in Brighton and spent three weeks down there. After three weeks we all felt it was working, and I was in.”

Having cleared that major and significant hurdle, the band set about working through material that would end up on Season’s End, rehearsing at Hook End Studios in Oxfordshire.

One afternoon, after a few lunchtime pints in the Crooked Billet pub in Henley-on-Thames, near the band’s bolt-hole, keyboard player Mark Kelly returned with news that he’d agreed that the band would play a small gig in the local boozer, under the unlikely name of Low Fat Yoghurts. It was another major hurdle, for Hogarth in particular, to negotiate.

“I freaked on the spot, because suddenly it had gone whoosh!” the singer recalls. “We were getting out of the bubble, and it was truly terrifying. I remember thinking: ‘Why haven’t I thought about this before?’ It was the acid test – being in front of a lot of people. I knew how passionate Marillion fans were, and I didn’t know what they’d think of me. It’s a lot to ask of anyone. Fish must have been a lot of the reason these people were so nuts about the band.

"The worse situation I could imagine was being in a room with them with no stage, no security, and them being able to reach out and strangle me! That was the point I thought: ‘What have I got myself into?’ I mentioned it to the band and they just said: ‘Oh, don’t worry about them, you’ll be fine.’ I didn’t even let my wife go to that show – and she still gives me gyp about it. But I was so frightened about what would happen.”

As with, it seems, almost everything else connected with Hogarth joining Marillion, the singer needn’t have worried. “The Crooked Billet was amazing,” Trewavas smiles. “A tiny little pub, but it became a huge event. It was supposed to be secret but it got out. There were people outside on the road and trying to get in through the window. But they loved it.”

Having ably cleared both hurdles so far placed in front of them, Hogarth and his new bandmates set about the task of crafting their musical ideas into tangible slices of new sound for the band.

“We wanted to keep the strengths of the band and yet move on and bring Steve in,” Trewavas explains, “not have four guys with a singer who’s on a wage.”

“I was just singing and had a little keyboard set up to tinkle away on,” Hogarth remembers. “I’d suggest things, and sometimes they’d say no and sometimes they’d like it. It was very natural and effortless. It felt very easy. Looking back I think the Season’s End album was a halfway house between the old band and what the new band was going to be. I hear old Marillion with a new boy singing on it.”

“It was a good starting point,” Trewavas agrees. “We were trying to develop and bring Steve through. Steve is much more of a natural singer than Fish was. Fish’s voice was always quite quirky. But it all seemed to gel really well.”

Despite having a wealth of musical ideas and lyric sets from novelist, comedian and musician John Helmer, the bulk of the music that Marillion set about working on for what would become Season’s End made it on to the final album, with only a handful of extra tracks available for B-sides for the three singles they would release.

Typically slow-building and atmospheric tracks like Easter and Berlin and epic prog like The Space…’nestled alongside two short, sharp shocks of hard rock in Hooks In You – which as the first single would herald Hogarth’s arrival – and the excellent Uninvited Guest.

“I don’t know where that came from,” Rothery says of ‘…Guest’ and its mildly ‘metallic’ leanings. “It was pretty good. I always do that a bit tongue in cheek. I find it kind of hard to think of myself… well, it’s like slide guitar. I always feel I kind of bluff it when I’m playing slide guitar. It’s fun to do, though, very liberating. One of those things where you can open the doors a bit wider, to go outside the box and have something more blatantly rock oriented.”

Some Marillion fans believe that Uninvited Guest, with lines like ‘I’m your fifteen-stone first-footer’, was a dig at the old frontman.

"Who knows?” Trewavas says, smiling conspiratorially.

“It’s a couple of things,” Rothery points out. “It’s based on Edgar Allan Poe’s The Masque Of The Red Death story, and also at the time it was about the Aids scare that was very prevalent at the time, with the words: ‘I’m the evil in your bloodstream/I’m the rash upon your skin…’”

“I must admit that getting that through was very interesting and poignant, and it worked on many different levels,” Trewavas says. “Although I must admit it was quite amusing that people might be led to think it was about Fish, but once again in a tongue-in-cheek manner.”

“We’d played around with it with Fish, actually,” Rothery adds. “Up in Scotland. And if you listen to the track Lucky, on his ‘Internal Exile’ album, the chorus is very similar. I need to have a word with him about that.”

Season’s End was Marillion’s first non-conceptual album. Concept albums were something the band had become well known for with Fish.

“That was Fish’s big thing… and then again, it wasn’t,” the guitarist says, smiling. “With Fish you sometimes got the feeling that some of the concepts were cobbled together at the last minute, if truth be known. I guess because Steve had written some of the lyrics and John Helmer had written some of the lyrics, there was never going to be a concept.”

Was the decision to record an album of disparate songs a deliberate move to enable Hogarth to establish himself from out of Fish’s looming shadow?

“Partly that, and partly because the concept album has had its time, really,” Trewavas offers.

Having endured the loss of a fan-favourite frontman, found a new singer and played their first gig at close quarters, the recording of such a pivotal album as Season’s End didn’t faze the band. But when Marillion’s record label EMI started making noises about the new material, the first signs of unease crept in.

“We didn’t feel like we were under immense pressure, but it got to the stage when we’d got together with Steve, and EMI started saying they needed to hear what we’d been doing before they thought about releasing anything,” Trewavas reveals. “We were fed up with that.”

“They knew that no matter what it was like they could sell X number of copies, so they’d release whatever we did,” Rothery says. “But we were fortunate to have come off an album like Clutching At Straws which, although not as popular as [1985’s] Misplaced Childhood had still sold over a million copies. We had that breathing space. If the previous album had been a flop we’d have been under a lot more pressure.”

“I was a bit nervous because they’d asked us for demos, and they hadn’t done that before,” Trewavas says. “They’d signed Fish and he was releasing an album, and it felt a bit like they’d signed him but were not necessarily keeping the band. As soon as they heard stuff, though, they were jumping up and down. Game on.”

Having gone through almost the entire Fish out/Hogarth in/Season’s End process with as little fuss as possible, and having finally been given the green light by EMI, the more nerve-racking prospect of facing both press and public now reared its head.

With Fish on the same label as Marillion and working on his debut solo album Vigil In A Wilderness Of Mirrors, it merely added to the pressure the band were now facing. Fish’s first single, State Of Mind, was slated for release at the same time as Season’s End.

“Yes, we never know whether he does that deliberately,” Hogarth smiles. “Maybe it’s coincidence, maybe it isn’t.”

“Well, we expected it, really,” Rothery sighs.

What they couldn’t have expected back in the autumn of ’89, however, was how warmly the rock press would welcome Hogarth.

“I remember the press taking to Steve very well,” Trewavas recalls. It did, of course, throw Fish back into the equation.

“That’s still the case really,” Trewavas admits. “ ‘So, tell me about Fish…’ And you think: ‘Oh, God, how many years on is this?’ Frustrating, really.”

“It still happens to this very day,” Hogarth says. “It’s a bit like asking a bloke who’s married to a woman to talk about her ex-husband – he’s always gonna say: ‘Well I never really knew him.’ It’s a bit strange for me. I met him a couple of times and he was always very nice to me. But I never really got to know him.

“I think the most daunting thing I had to face in that respect was meeting the president of the Dutch fan club. He came down to rehearsals and gave me the grilling of a lifetime. The Dutch can be very direct.”

If Marillion's inner confidence need a boost, it got one when, having embraced Hogarth like an old friend at the video shoot for Hooks In You at London’s Brixton Academy, the fans sent Season’s End into the UK album chart at No.7. It made the prospect of going on tour and facing ardent Marillion fans around the world slightly less daunting.

“I think if there was any worry it was how would the audience take to it, because obviously Steve’s such a different performer to Fish,” Rothery muses. “But it wasn’t the case at any gig. It might take a few songs for people to make their minds up, but you could see them smiling approvingly halfway through the set.”

There was, of course, also the matter of the set-list. The band obviously wanted to include as many new songs as possible, but there was no way they would get away without delivering a string of the expected, older Marillion numbers.

“The band helped me a lot with that, because they gave me a list and told me to choose, and anything I was unhappy with went in the bin,” Hogarth says. “So I just chose the songs I felt I could relate to. Some of the stuff Fish had written was wrong for me. It was either too intense or angry, or too gothic, which is just not where I’m at. The band were totally cool with that.

“My approach to singing is… how shall I put it… more tuneful and more musical than maybe Fish’s approach, which often had a lot more to do with anger and frustration. I can produce anger and frustration if I feel it, but I have to be feeling it. That still left us with masses of scope with the old songs. I just sang them in my own way and I tried not to overdo it.

“And I tried not to stroll on stage as if I owned the building, because there’d be people out there who’d be thinking: ‘Well, who the hell does he think he is?’ I tried to take the approach that here I am, and I’ll try and sing something if that’s alright. Because I almost had the approach that the audience had more right to the band than I did. They knew Marillion better than I did, so instead of demanding their attention I thought I’d just do my thing and hopefully they’d come around.”

Equally, initially the rest of the band must have felt it strange to be sharing the stage with the newcomer. “That was quite hard for us as well. We were trying to project more as a band to help Steve out,” Trewavas says. One assumes the idea that it might not work live was still hanging over the band’s head like some kind of sword of Damocles.

“There was the potential, but I don’t think I ever thought that once,” Trewavas offers. “We’d done the video, and consciously decided to use a big production so that would help too when we were all on stage, to try and make up for something that might not have been there.”

“It made us all the more determined,” Hogarth adds. “Every night was something to conquer. It was like a marathon with hurdles, and each gig was another one you jumped. There was a great feeling in the band, very much all-for-one and one-for-all. We weren’t just playing gigs, we were winning territories. And any one of them could have been a set-back, but it wasn’t. As luck would have it we celebrated my first anniversary in the band in Rio De Janeiro, with a champagne breakfast in the best hotel in the city. It felt pretty good.”

Season’s End firmly re-established Marillion as a major player in the rock game with almost effortless ease after what could have derailed many other bands. In subsequent years albums like Holidays In Eden, the wonderfully conceptual Brave and This Strange Engine, the first album the band released after splitting from EMI, have enabled Marillion to progress as one of the most unique rock bands in the country.

A return to EMI for 2001’s excellent Anoraknophobia solidified that position. And with Marbles being the first album the band released through the process of raising money through their dedicated fanbase, they’ve proved they can survive as a self-contained entity outside of major record labels.

Steve Hogarth became comfortable seeing himself as Marillion’s frontman a long time ago. “It was probably with Brave that I felt I was really part of the band,” he says. “But if I’m really honest, I’ve laid those ghosts to rest only quite recently in my head. Even sitting down for an interview and talking about Fish used to piss me off. I’ve got to that point now where it doesn’t bother me, and my self-confidence is better.

"But it’s only recently that I’ve begun to feel as if this is just as much my band as it is Steve’s or Pete’s. It’s taken me years to get to grips with that."

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 68, in May 2004.

Writer and broadcaster Jerry Ewing is the Editor of Prog Magazine which he founded for Future Publishing in 2009. He grew up in Sydney and began his writing career in London for Metal Forces magazine in 1989. He has since written for Metal Hammer, Maxim, Vox, Stuff and Bizarre magazines, among others. He created and edited Classic Rock Magazine for Dennis Publishing in 1998 and is the author of a variety of books on both music and sport, including Wonderous Stories; A Journey Through The Landscape Of Progressive Rock.