That Metallica didn’t take the 25th anniversary staging of the Woodstock festival entirely seriously was evident even before the San Franciscan quartet followed Nine Inch Nails onto the site’s North Stage on the evening of August 13, 1994. Had they perused the festival’s official merchandise stalls, the 350,000 music fans who streamed on to Winston Farm in Saugerties, New York, that weekend would have spotted a bespoke ‘Metallistock’ t-shirt featuring the band’s ‘Scary Man’ mascot with dollar bill symbols in his eyes, flowers in his hands and a ‘peace sign’ pendant around his neck, under which was scrawled the words ‘Hippie Shit’.

Billed as ‘2 More Days of Peace and Music’, the event’s faux nostalgia might have captured the imagination of America’s ‘baby boomer’ demographic, but for Metallica it primarily represented a tidy paycheck and an opportunity to piss about in front of a live TV audience. And so, following James Hetfield’s cheery “Fuck you!” greeting, heavy metal’s biggest band chose to reintroduce themselves to the American public by opening their sub-headline slot with Breadfan, an obscure B-side track written by cult Welsh prog-rock trio Budgie.

Further mischief was to follow, with James introducing perennial live favourite Seek & Destroy as a new song written by Jason Newsted, telling the crowd “since he wrote it, he’s going to have to sing it”. Even those in on the joke, however, were confused to hear the Kill ’Em All-era standard’s mid-section melt into an extended blues-rock jam. Though only the four men onstage knew it, this was the watching world’s first taste of what would become Metallica’s controversial sixth album, Load.

- How to sound like Metallica's James Hetfield

- How to sound like Metallica's Kirk Hammett

- The best Metallica merch 2020: amazing gifts for the Metallica fan in your life

- On a budget? Here are the best budget turntables

James Hetfield and Lars Ulrich began work on the follow-up to Metallica’s self-titled fifth album in the spring of 1994, less than one year after their Nowhere Else To Roam tour concluded at the Rock Werchter festival in Belgium. Much had changed in the music world since the release of the phenomenally successful Black Album: Bruce Dickinson had walked out of Iron Maiden; Nirvana frontman Kurt Cobain, the latest media-anointed ‘saviour of rock’, had recently killed himself at home in Seattle; and in California, Green Day and The Offspring had just released Dookie and Smash, two albums that would finally ‘break’ punk rock in the US.

Metallica’s founding members returned to songwriting duties utilising the tried-and-trusted methodology they’d developed when they first got together as teenagers, studiously sifting through James’s home-recorded ‘riff tape’ cassette collection in order to identify musical motifs that might form the spine of new songs. Working in a basement studio in Lars’s hilltop Marin County home – a facility dubbed ‘The Dungeon’ – the guitarist and drummer set to arranging and committing these ideas to tape.

On November 28, ‘Streamline’ (later retitled Wasting My Hate) became the first new Metallica demo recording in four years. On November 30, a second song, ‘Load’, (aka King Nothing) was tracked. Before the year’s end, three more recordings – ‘Devil Dance’ (later Devil’s Dance), ‘Fixer’ (aka Fixxxer) and ‘Mouldy’ (Hero Of The Day) were in the can. By Easter 1995, the duo had 13 songs – including The Outlaw Torn, featuring that bluesy riff previewed at Woodstock – mapped out. And still the ideas kept coming.

“All this material had built up on the road,” James explained. “There were bags and bags of tapes with riffs on them… stuff we had accumulated from five years of not writing. First it was like, ‘OK, let’s stop at 20 songs.’ Then we would get going and say, ‘All right, we’ll stop at 30.’ It was fucking crazy.”

Metallica entered The Plant studios in Sausalito, California on May 1, 1995 to begin tracking the album, retaining Bob Rock’s services as producer following his sterling work on the Black Album. At the outset, James and Lars laid out their desire that the new songs should be looser, more organic and more spontaneous than previous recordings, an aim Bob Rock tried to accommodate by encouraging the four musicians to play off one another in the studio, experiment with tunings, textures and tones, and keep open minds in regards to the flow of ideas. To ensure that the band were not overwhelmed, Bob also suggested that they should focus upon roughly half of the 27 songs sketched out at The Dungeon; there would be time in the future to revisit the remaining material.

“We’re almost having fun in the studio,” Lars revealed as the sessions got underway. “We’re doing basically what we hoped for in our wildest imagination, which is not getting caught in some anal torment of precision and tightness. The new songs we’re writing just called for a looser, livelier type of thing and we set our goal with this record to try and capture more the spirit of the songs than worrying about the technical stuff.”

The first real indications of the new mood in the camp came in mid-August with the premiere of new tracks, 2x4 and Devil’s Dance, at a fanclub members-only show convened as a warm-up for the band’s first headline appearance at Donington Park. In November, James called another ‘time out’, to embark upon a trek into the wilds of Wyoming. The singer had been informed that his father, Virgil, had advanced-stage cancer, and would not beat the disease, and he wished for some time alone to process the information. Alone with his thoughts in a tent in the snow-covered wilderness, the singer used lead-tipped bullets to write down ideas that would later form some of his new album’s most emotional, open-hearted lyrics.

- What happened when the Big Four played together for the very first time

- That time all of Metallica dressed up as Lemmy to play his 50th birthday gig

Upon his return to The Plant, James learned that his bandmates had broken new ground on the album. Encouraged by Lars, for the very first time Kirk Hammett had laid down some rhythm guitar tracks in the studio. Wisely, the guitarist had not sought to emulate James’s forensically precise riffing, instead devising chord patterns which complemented the central riffs. Sensitive to the idea that Metallica’s frontman might view Kirk’s additions as an affront to his vision for the songs, Bob assured James that he could wipe the tracks if necessary, but repeated listens convinced the guitarist that there was merit to this new approach, and harmony prevailed.

Conscious that their charges’ new-found sense of experimentation might render their studios sessions entirely open-ended, Elektra Records, Metallica’s US label, set May 1, 1996 as the date for their forthcoming album to be mastered. In March, operations shifted to America’s East Coast, with the band commandeering three recording studios in New York: two rooms at Right Track Recording on West 48th Street and an additional space at Quad Recording, across the street at 723 7th Avenue. With the sessions still ongoing, the quartet then invited the world’s media to New York to hear previews of the album, and this writer was among those selected to attend.

Looming deadlines notwithstanding, Metallica appeared utterly relaxed and carefree as they threw open the doors at Right Track. When an unmastered CD-R of new songs was aired on the studio’s stereo system, a giddy Kirk added enthusiastic air guitar flourishes while James, Jason and Lars sang along lustily. On first listen, the quartet’s new recordings sounded staggeringly powerful, but a pronounced shift in sound was immediately apparent, with the influence of 1970s hard rock masters Aerosmith, ZZ Top, Ted Nugent and Lynyrd Skynyrd notable.

- Metallica - One: The story behind their breakout single

- Matt Heafy: why I love Metallica's Master Of Puppets

Before you start working on a new record, you wonder if you can still deliver,” shouted Lars over the music. “But once James and I lock in and start work together, it’s pretty much unstoppable. The bottom line is, playing and writing with James still gets my dick as hard now as it did in ’81.”

When it was suggested to Lars that Metallica’s new songs implied the band were becoming ever more mainstream and, heaven forbid, respectable, the drummer let out an exaggerated sigh.

“We’ve had that for years,” he countered. “When we put Fade To Black on Ride The Lightning, people were saying Slayer were the alternative to Metallica because we were playing this acoustic garbage. People should get off their asses to topple us. Like, here’s a guitar – blow us away if you think you can.”

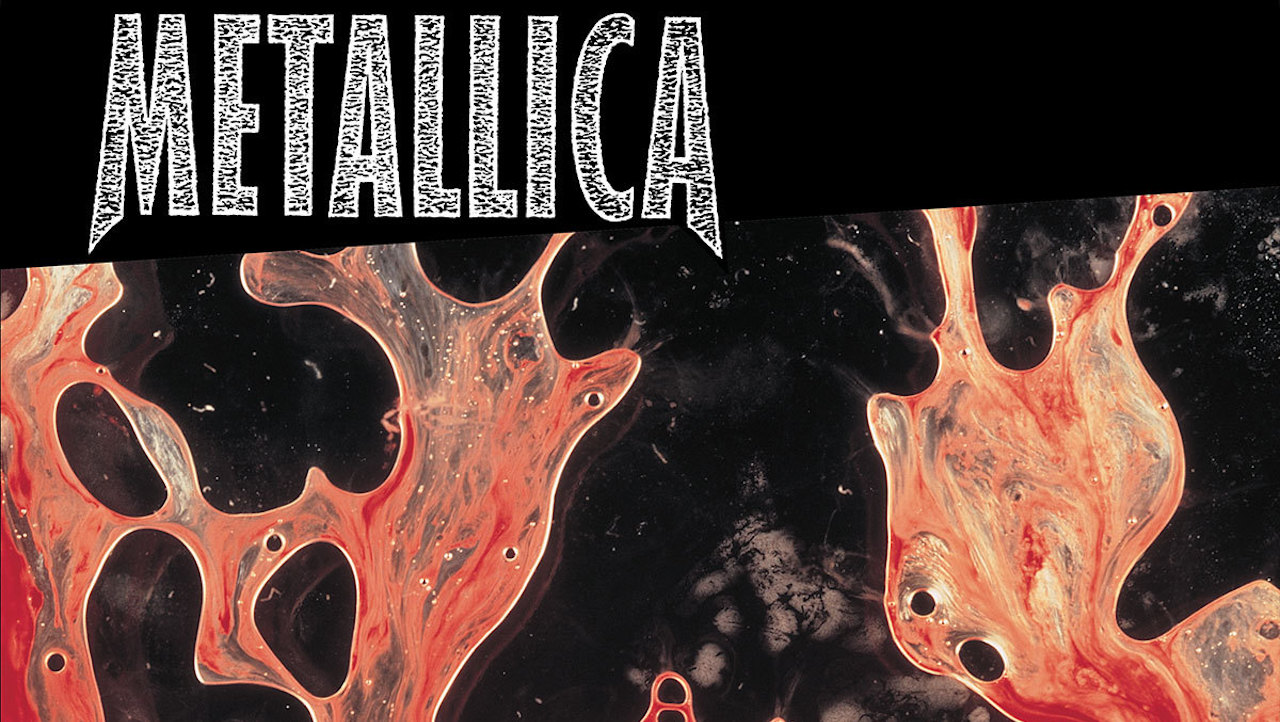

Metallica’s new album, Load, was released in the UK on June 3, 1996. Though advance press on the record was overwhelmingly positive – Metal Hammer awarded the collection 4.5 out of 5, stating that the band “have continued their evolution into the best heavy metal band of the modern age” – reaction from fans was decidedly mixed. For some, the adoption of 70s rock tropes (and indeed a pronounced country influence on the ballad Mama Said) was regarded as a betrayal of the band’s heavy metal roots: more alarming still was the imagery which accompanied the release. The fact that the band had altered their iconic logo served notice of a wholesale image overhaul. Each of the four musicians now sported short hair, and were photographed sporting eyeliner, tailored shirts and, in Lars’s case, a fur coat Elton John might have deemed ostentatious. The album’s striking cover – a photograph by Brooklyn-born artist Andres Serrano created by mixing the artist’s own semen and bovine blood between two sheets of Plexiglas – was intended to evoke the idea of rebirth, but for many old-school Metallica fans, the band they had grown up with was now dead. Entirely conscious of the indignation their new sound and look was provoking, the band were bullish to the point of arrogance.

“I think we made a really fucking great album, and people aren’t going to walk away from our music even if they think we look like ‘poofs’,” said Kirk bluntly. “At the end of the day, it all begins and ends with the music. I think we’re now much more than a heavy metal band.”

- “Whose f**king idea was this?”: how Metallica’s made the spectacular S&M2

- Dave Mustaine reviews Metallica's Hardwired… To Self-Destruct

In retrospect, much of the outrage Load inspired seems comically overblown. At its best – on first single Until It Sleeps, on the stirring The Outlaw Torn and the seething Bleeding Me – the album offered a bold, mature and liberating re-imagining of the Metallica sound. The album’s biggest fault however, was quality control. 2x4 and Ronnie are, in hindsight, a bit throwaway, while too much of the material – Cure, The House Jack Built and Thorn Within in particular – is simply mediocre. Metallica’s openness to experimentation is laudable, but in their quest to push boundaries, James and Lars appeared too easily satisfied with material that, a decade earlier, would never have made it out of their El Cerrito garage. In 2003, looking back on an album that had now passed the five million sales mark in America alone, Lars acknowledged as much.

“In retrospect, the Load/Reload stuff could have used a little bit of editing,” the drummer admitted. “But when James and I ended up writing 27 songs for that album in the fall of ’95, we were damn well going to put all 27 on the album. In retrospect, could the world have done with 12 or 15 less of those? Probably, but back then we didn’t have an edit button on our instrument panel.”

James was even more blunt when interviewed that same year.

“[We were] trying to be something we weren’t and then that confused us even further musically,” he stated. “There’s quite a few great songs on there that could have been greater if the cover and the pictures were different I think. A lot of the fans got turned off quite a bit from the music but mostly, I think, from the image. It just doesn’t work. You absolutely have to evolve, but let’s have it evolve naturally. It didn’t seem natural to me.”

“They were enjoying life,” says Bob in the album’s defence. “When you become the biggest band [in metal], you become a target. We always want the people we love and idolise and look up to to stay the same. Accomplishing The Black Album and three years of touring and everything, it took them to a different place. I think they started letting down their guard and became… people. That’s what I saw and that’s what I enjoyed being around.”

As is so often the case, perhaps the last word on Load should be left to Metallica’s biggest fan, their ever-vocal drummer.

“It felt like a big ‘fuck you’,” says Lars. “Not to the fans, more to the conservative element that was running through the heavy metal community, the predictability of all of it. It was a challenge to the heavy metal community and I’m proud of that, because once in a while the heavy metal community needs a good fucking kick up its ass.”