Metallica released their first music video 35 years ago. This is how it ruined my life.

A Metal Hammer writer looks back on the scarring effects of the video for Metallica’s One, which debuted on January 22, 1989

On January 22, 1989, Metallica finally made it onto the airwaves with their video for …And Justice For All standout One. The clip catapulted the Four Horsemen into living rooms around the world and only strengthened their grip as they climbed to metal’s pinnacle. However, in this 2015 op-ed, one Metal Hammer scribe writes about the life-long scars its brutal imagery gave him.

“I’m surprised you’re not scared of this,” said my mother as I sat with my eyes fixed on the television.

When I was 12, I’d dutifully record The Power Hour, a weekly show on ITV which was broadcast during the small hours.

At the time, Metallica didn’t have any proper videos. I can only remember seeing a grainy video of the band performing For Whom The Bell Tolls in Oakland in 1985. But that was it.

But one morning in January 1989, that – and my life – was all about to change. The show’s presenter Nikki Groocock announced that they were to play a new video from Metallica – a promo for their One single. It felt like a big deal, so I remember pausing the video, pouring myself some cereal and making another mug of coffee. I drank a lot of coffee when I was 12.

I remember feeling slightly unsettled a few months earlier when I first listened to the song. I bought and played …And Justice For All for the first time on Bonfire Night in 1988. I recall this vividly because the firework display outside seemed to blend into the song’s opening battlefield sound effects and those eerie opening notes. And my non-metal-loving friends said I was sad for staying in to listen to music.

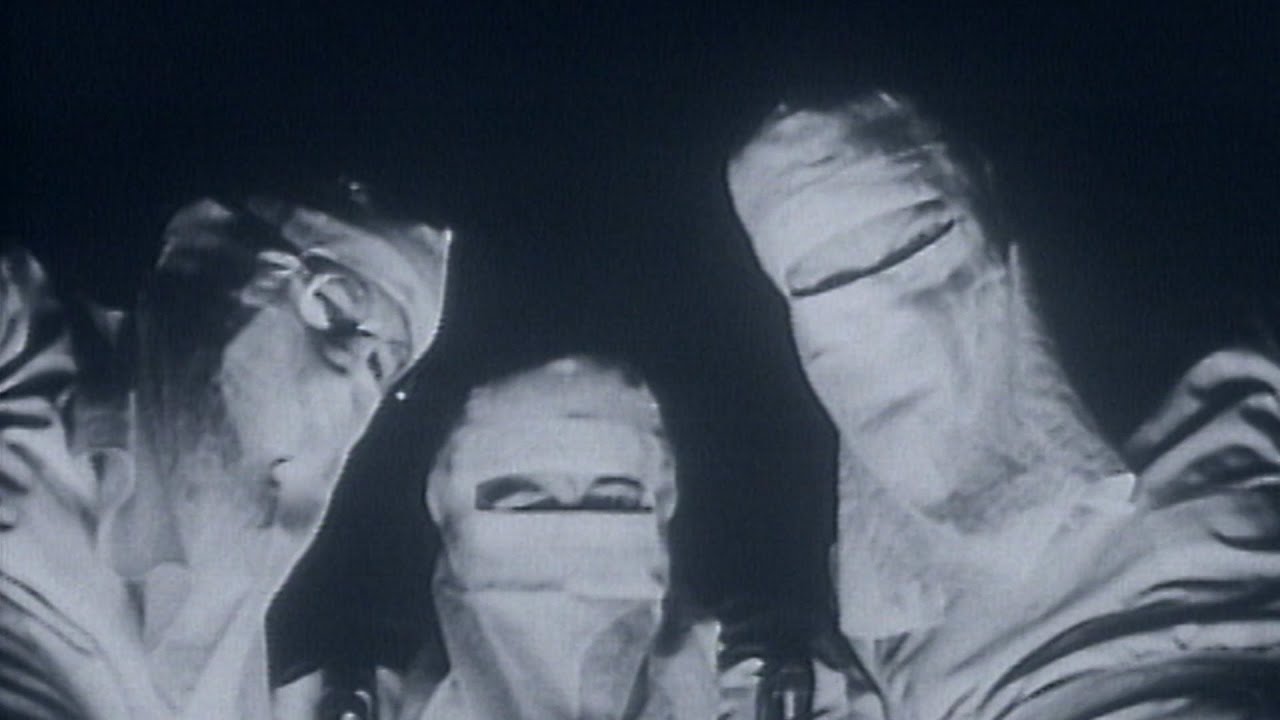

Shot in black and white and layered with a cold blue hue, the video opens with close-ups of the band’s various body parts: the back of Jason Newsted’s head, James Hetfield’s body, his face intermittently obscured by the shadow of an overhead ceiling fan. The band’s role in the video was simple: tear through the song in an empty warehouse space in Long Beach, California. Grimace and headbang. That was it. They were all dressed in black, save for Lars Ulrich, who chose to wear one of the band’s own 1988 white tour t-shirts – the one with his own face on it, just to drive home who he is and which band he plays in.

Sign up below to get the latest from Metal Hammer, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Now, at this point, I’d go through the video and break it down, minute by minute. But the truth is that I’ve seen the video three times in full, and they were all on that winter’s morning. It’s the film they used clips from that’s responsible for a monthly recurring nightmare. And I’m never watching it again.

Johnny Got His Gun was an anti-war novel written by Dalton Trumbo in 1938 and published a year later. The story is centred around a young American man called Joe Bonham who serves in World War I and gets hit by an artillery shell.

As the story unfolds, he realises that he has woken up on a hospital bed with no arms, no legs and no face. There’s a very graphic chapter in the book where he realises he’s lost his eyes, nose and mouth by exploring the gaping wound with his tongue. He’s also deaf and can only communicate to nurses and soldiers via Morse code, which he does by bashing his head on a pillow.

A film – directed by Trumbo himself – was released in 1971 and stars Timothy Bottoms. It also features appearances by Jason Robards, David Soul and Donald Sutherland, who makes a cameo as Jesus Christ in a dream sequence. It flits between black and white and washed-out colour, as we see Bottoms alone in a stark hospital room with a mask covering what’s left of his face.

Even typing this now makes me feel slightly sick and my shoulders feel considerably heavy. Who’d have thought a rock video had the power to ruin someone’s life?

After watching that video a few times, I began to overthink what I’d just seen. My cereal went uneaten and my coffee grew cold on the windowsill. I remember sleeping with the light on that night. I can’t remember sleeping alone in the dark again after that, actually.

This experience has bled into my life in all sorts of ways. The following year, I had a massive panic attack during a school trip to London’s Imperial War Museum. Their visitor attraction, the Trench Experience, recreates the sounds and smells of being on the frontline. Of course, my curiosity quickly turned into blind panic as I pushed through my classmates and ran outside, pausing to retch drily into a bin.

I had a nightmare that night.

On October 28, 1992, I got to see Metallica at Whitley Bay Ice Rink. This was during their colossal Black Album tour, where they brought their Snake Pit stage set up and played a 20-minute film in lieu of having a support band. Lars’ face would be beamed onto a screen and he’d talk to the fans from their dressing room before a documentary of sorts would kill time before their set. A brief clip from One was shown and I spent the entire gig wondering if I’d get to sleep when I got home.

I had a nightmare that night.

When the band released their 1993 boxset extravaganza, Live Shit: Binge & Purge, I tried fast-forwarding the film from their set at the San Diego Sports Arena. I managed to see the One clip then, stopped the tape and never watched the rest of it.

I had a nightmare that night.

Around this time, I’d also spend a lot of days at my friend Stephen’s house listening to records and plucking out bass lines from slower rock songs. A small dene divided the two housing estates where we lived, and it reminded me of a scene from the film, where the hapless Joe Bonham runs down a bank before the mortar attack. Some nights I’d sprint home with my heart beating out of my chest; some nights I’d walk home the long way round. And, I’m ashamed to say, Stephen escorted me across the bridge a few times, laughing his head off as I went back to safety.

I had a nightmare every night.

When I moved to London in 1994, I would regularly go to Tower Records in Piccadilly Circus. One day, I clocked the Johnny Got His Gun paperback on a shelf and snapped it up immediately. I’ve yet to experience a surge of fear quite like it since.

From the time it took to get from Piccadilly Circus to Oakwood tube station, I must have read half of the book and blinked perhaps twice. It was very easy to read: its pace quickens with a lack of punctuation during Joe’s fevered rants. I drank myself to sleep that night, which took a few pints on an empty stomach.

Over the years, I’ve had so-called friends hum One’s opening bars just to see my good mood change in an instant. I don’t like fireworks and I can only half-enjoy Blackadder Goes Forth. I can’t wash my hair with my eyes closed. I will often sleep with my feet and arms sticking out of the bedsheets. I don’t like people covering their faces with their hands and have developed the knack of turning a TV off the second I sense the video will start. It’s quite impressive, actually.

Why am I so scared of this video? I’ve always had a thing about World War I. Maybe it’s that. The idea of locked-in syndrome terrifies me, too. But it’s definitely the cloth mask covering Timothy Bottoms’ disfigured face and his feeling of utter helplessness that makes my stomach turn. And his weary voiceover makes me want to run out of the house. People I’ve bored to death talking about it agree that it’s a bleak premise, but they’re able to go to the toilet without turning every light on in their house.

So, two years ago, after consuming several glasses of vodka, I attempted to watch Johnny Got His Gun in its entirety.

I didn’t do this alone – are you mental? I watched it with my girlfriend, who I once asked to put her arms on top of the duvet to double-check she wasn’t a double amputee. She definitely isn’t.

‘Let’s watch it, draw a line under it and move on’, I probably slurred as I turned on my Macbook. It’s on YouTube in its entirety, if you’re feeling brave. With a sphincter so tight it could squeeze the life out of a single human hair, I managed 10 minutes before slamming my laptop shut. I admitted defeat, before realising I’d plunged the bedroom into complete darkness. I probably deserved that, to be fair.

This whole paralysing fear of a song, a film and a music video came to a head when I once did a phone interview with Lars. I went off-topic – the interview was supposed to be about Through The Never – and asked him whether the video had affected him to such an extent. He admitted it hadn’t, but he ended up apologising for causing me nightmares.

I didn’t have a nightmare that night. I had two, including a vivid scene where I was locked in a room with the film on an endless loop.

So thank you, Metallica. Thank you very fucking much.

Originally published in 2015.

Born in 1976 in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Simon Young has been a music journalist for over twenty years. His fanzine, Hit A Guy With Glasses, enjoyed a one-issue run before he secured a job at Kerrang! in 1999. His writing has also appeared in Classic Rock, Metal Hammer, Prog, and Planet Rock. His first book, So Much For The 30 Year Plan: Therapy? — The Authorised Biography is available via Jawbone Press.