As John Lydon snarled on Public Image Ltd's debut single in October 1978: ‘Two sides to every story.’ In other words, you’re either on one side of the fence or the other; you’re a believer, or you’re a sceptic; you’re for, or you’re against.

Me? I won’t be making any crazy assumptions; I’m no Erich von Daniken. I’m just going to tell you – as straightforwardly as I possibly can – about some eerie events that took place in 1986, eight years after that Public Image Ltd single reached the UK Top 10. But before the weirdness kicks in, let’s begin on a lighthearted note…

Lars Ulrich of Metallica has just arrived outside my house in a rusty brown Fiat Panda. Through the car’s side window I can see Denmark’s foremost drummer narrow his eyes and gaze somewhat critically at the Barton abode: a modest, three-bedroom detached dwelling way out to the west of London, on the environs of Heathrow Airport; a typically English suburban residence – if you can disregard the incessant rumble of jet engines and the occasional jumbo rattling the roof tiles. But it’s my home.

Ulrich, dressed anonymously in plain black T-shirt, pale blue, tight-thighed jeans and signature white trainers, disembarks from the Panda. The car door doesn’t so much ‘clunk’ as ‘ding’ shut, recalling the sound made by a WWE wrestler when he brains his opponent with a flimsy metal tea tray. As the door settles on its hinges, the cheap Italian four-wheeled tin box quivers on its suspension springs in protest. I half expect the headlamps to explode and the bonnet to fly open in the manner of a clown’s car puttering around the arena at Chipperfield’s circus.

This is not exactly the coolest entrance in the world (leave that for stretch limos and Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame ceremonies, but Ulrich remains unabashed.

“Hey, Geoff,” he drawls as he walks up my rutted garden path – a poor replacement indeed for the traditional red carpet. “I thought you would’ve lived in a mansion.”

“On a British rock journalist’s pay?” I retort as we shake hands enthusiastically. “You must be joking, Lars. Come on inside.”

We adjourn to the kitchen and rustle up some mugs of sweet tea. Photographer Ross Halfin – the proud owner and driver of the Panda, believe it or not – is with us, along with a host of supermarket carrier bags full of zillions of colour transparencies. And, happily, they’re not Halfin’s holiday snaps, they’re his latest pictures of Metallica.

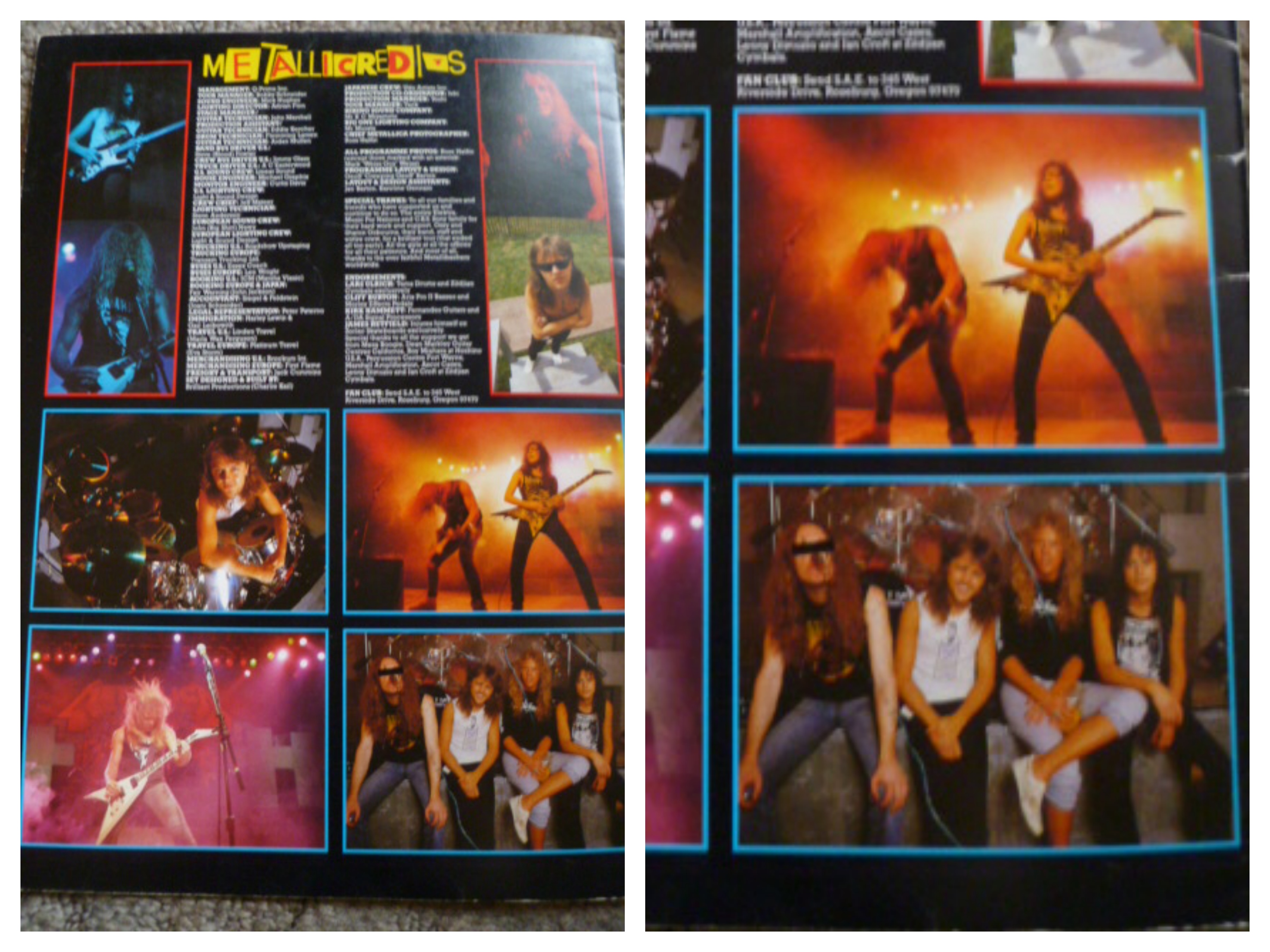

We’ve gathered together to discuss the content of and choose the photographs for the band’s Damage, Inc. tour programme, which I am apparently designing. Halfin has somehow convinced Ulrich that I am a first-rate graphic artist – even though my layout skills don’t really extend much beyond cutting-and-pasting a list of tour dates onto a page of Kerrang!.

But before we get down to the nitty-gritty, Ulrich is being assaulted by a small child scuttling around in a bright red baby-walker.

“Hey, little guy, be careful there,” Ulrich says kindheartedly, as said baby-walker collides with his left ankle. My infant son Ben grins back angelically. And then rams Ulrich with his baby-walker again.

(This potentially life-changing encounter with an all-time drumming legend sadly left little musical impression on Ben, who is now in his late teens. As I write, he is probably twirling his twin decks at some seedy garage club somewhere as he performs under his nom de plume, DJ Double-B. Ah well. You can kill ’em all, but you can’t win ’em all).

We go up to the side bedroom now, which I’ve tried to tart up as best I can as a professional tour programme designer’s studio. And I think I might just get away with it – just as long as Mr. Ulrich doesn’t notice the cringingly embarrassing floral wallpaper, the off-white shag-pile carpet, the dying rubber plant, the broken 1960s lava lamp, the musty smell of damp in one corner, the…

‘Blood will follow blood/Dying time is here/Damage incorporated’ – the chorus of Damage, Inc., from Metallica’s Master Of Puppets album.

Now this is where the weirdness kicks in. After hours of typically intense Ulrich-style discussion, the mountains of Metalli-pix have been eroded away into mounds of more manageable molehills. A tour programme strategy has been formed, a page plan drawn up and a deadline determined. With a final, explicit warning from Ulrich: “This absolutely must be the final photograph on the final page, Geoff. No question. He’ll be so pissed, so annoyed. Make sure it happens.”

While the drummer joins Halfin to head back east to Raynes Park in the rattling Panda, the real work begins.

I’ll just take a moment here to explain how the design process worked in these pre-desktop publishing, dinosaur days. All you really needed were basic tools such as a bunch of brightly coloured pens and plenty of large-sized A2 paper, plus a slide projector (I’d hired an archaic one from a local camera shop on this particular occasion). You simply drew up the outline of your page on a sheet of paper and pinned it onto a suitably flat wall. You then filled the projector’s carousel with transparencies, darkened the room and shone a succession of images onto the paper, locating them inside the pre-drawn page border. The images could be resized by using the projector’s zoom lens to zoom in and out, or they could be repositioned by moving the projector from side to side or tilting it up and down.

The next step would be to kneel down in front of the piece of paper mounted on the wall – backbreaking work, this – and trace around the images projected onto it. Repeat ad infinitum to build up the picture placement process, then finalise the sketched page design and add written instructions to the printer as appropriate.

It’s simple enough, but extremely labour intensive.

Anyhow, I’m rattling along at a fairly good pace, until I get to the tour programme page devoted to bass player Cliff Burton, when the damn projector starts playing up.

The carousel jams, and maybe half a dozen transparencies get stuck too close to the projector’s scorching light-bulb. There’s an awful smell akin to someone’s hair being set on fire, and a sizzling sound like super-heated streaky bacon. Globules of melted plastic drip on to the floor.

Cliff Burton begins to burn…

Metallica’s Damage, Inc. tour was a monster in more ways than one. It kicked off on March 27, 1986, at the Coliseum in Wichita, Kansas. April dates began on the first at the Kemper Arena in Kansas City, Missouri, and ended at the Nassau Coliseum in Uniondale, New York, on April 29.

The band continued their epic Stateside trek from May right through to the beginning of August, cramming in a short visit to Europe on July 5 and 6 to play, respectively, Saapasjalka in Wvaskyla, Finland, and the famed Roskilde Festival in Copenhagen, Denmark. The European leg of the tour began in earnest on September 10 in Wales, at Cardiff St. David’s Hall. Then, 17 days and 12 gigs later, the gruelling schedule came to a shuddering – better make that skidding – halt. It’s just before dawn on Saturday, September 27, on a godforsaken highway winding up the frozen mountains between the Swedish capital of Stockholm and Copenhagen. Metallica’s tour bus is travelling along at a fair pace, its six wheels kicking up a shroud of snow through which shimmers a gloomy half-light. Suddenly the bus hits some treacherous black ice and begins to slither out of control on the wrong side of the road. It slides and slews for 50 feet or so before falling sideways into a ditch near the tiny town of Ljungby. Cliff Burton, aged just 24, is sleeping on a bunk at the back of the bus. When the tour bus begins to topple he’s thrown out of a window. There’s nothing anyone can do to prevent the rolling bus from landing on top of him, crushing him to death.

Burton was, in many ways, Metallica’s talisman. A firm fan favourite; a lucky charm in loon pants. But whatever magic powers he possessed were abruptly curtailed on that chilling night in autumn 86, when winter arrived early for Metallica.

This isn’t the place for a misty-eyed eulogy. That’s not the point of this particular exercise. But it’s worth remembering that although Burton was popularly known as ‘the most headbanging bassist’, he was much, much more than a goofy West-Coast longhair with a crowd-pleasing, windmill playing technique.

Burton provided the ideal counterpoint to Ulrich’s vigorous, pneumatic drum beats and the low-end, twin-engined growling of guitarists James Hetfield and Kirk Hammett.

Like Andy Fraser of Free fame, Burton was in a class above your archetypal solid, dependable four-string plucker. As well as possessing the ability to pummel out a booming, unremitting, heart-hammering beat, Burton – unusual in this genre of metaldom – had an instinctive sense of where to add clever nuances, creative runs and chunky fills. To him, the bass guitar wasn’t just part of a rhythm section, it was a lead instrument.

Burton joined Metallica in late 1982 from Trauma, replacing the lightweight Ron McGovney. Some might say the addition of Burton was the single most important factor that helped extricate Metallica from California’s seething thrash metal swampland. I wouldn’t necessarily disagree with that.

Just before Jason Newsted was expressed in from Flotsam & Jetsam as Metallica’s new bass player, I remember my kolleague (sorry, old habits die hard) Xavier Russell writing a heartfelt tribute to the Bell-Bottomed One in Kerrang! magazine.

But, Xavier being Xavier, he couldn’t resist a hint of irreverence. At the end of his accolade, he made a close-to-the-bone reference to a track on Metallica’s _Ride The Lightning _album: wasn’t it strange, Xavier remarked, that in the light of the events surrounding Burton’s death Metallica had once recorded a song called Trapped Under Ice?

At the time, Xavier was fiercely criticised for his gallows humour. Many believed he had overstepped the mark. But, looking back, it could have been another strand in this strange tale.

Monday, September 29, 1986. Off the train and out of the lift at Mornington Crescent Underground station, across traffic-choked Hampstead Road and up the stairs into Greater London House – the old Black Cat cigarettes building. Turn right at the lobby area and push through thick wooden double doors into the reception of Spotlight Publications, publishers of Kerrang! magazine.

I’m late for work, I’m sweaty and I’m flustered – and I’m wondering how we’re going to deal with the news of the awful events that have taken place in Scandinavia over the weekend.

Meanwhile, the person sitting behind the front desk is looking at me with wide-eyed astonishment. The look on his face is a mix of abject horror and blessed relief.

Now, Michal, the Polish security guy, has a decent enough grasp of the English language, but occasionally he gets confused and he doesn’t hear straight.

This Monday morning, I step back in surprise as Michal gets up from his chair, his face now breaking out into a great big, beaming smile. He hurries over and gives me a crushing bear hug.

“I have been thinking that you were dead!” Michal exclaims. “The readers have all been telephoning up, and I have been thinking that you were dead!”

Like I say, sometimes Michal’s ears play tricks. But in this case it’s an aural illusion of David Blaine-like proportions.

What happened was that while he was manning Spotlight’s reception on Saturday and Sunday, Michal had had to field dozens of phone calls from distressed Kerrang! readers.

All weekend, he says breathlessly, distraught metal fans were trying to get through to an empty Kerrang! office with the news that some bus had skidded on ice on a road somewhere and someone had died.

But Michal isn’t a Metallica fan, and he’s never heard of Cliff Burton; to him, it sounded like the callers were saying: ‘Geoff Barton’.

I should have known what would be waiting for me in the Kerrang! office when I finally escaped Michal’s clutches. A bundle of Damage, Inc. tour programmes sitting on my desk. And a few final twists in the tale.

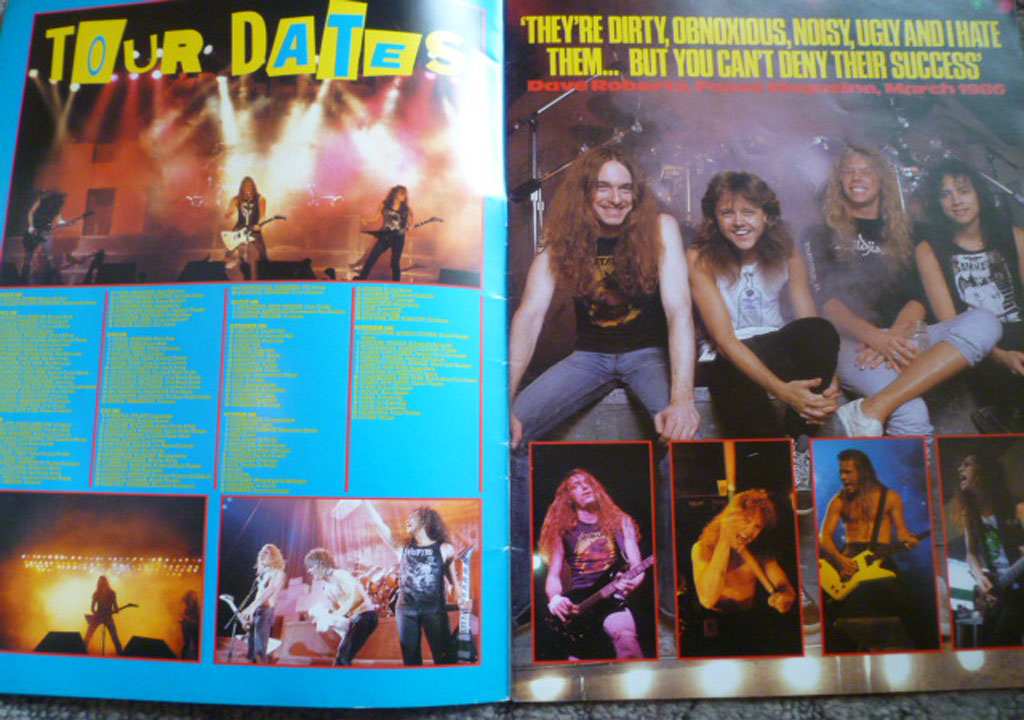

The programme has turned out pretty well for an amateur designer, I reflect as I flick through its pages. And I raise a wry smile when I come across a quote from Dave Roberts of Faces magazine, which Lars Ulrich had demanded be used in big type on a prominent right-hand page early in the book: “Metallica are dirty, obnoxious, noisy, ugly and I hate them… but you can’t deny their success.”

Then I remember the other thing Ulrich had insisted upon: “This absolutely must be the final photograph on the final page.”

I flip the programme over, momentarily wincing as I see how my name has been credited: ‘Programme layout and design by Geoff ‘Creeping Geoff’ Barton’ (obviously a reference to Creeping Death, another track from Ride The Lightning – and also not the most appropriate play on words, given the weekend’s events).

Whatever. I cast my eyes down the page and there, in the bottom right-hand corner, is the photograph Ulrich (“He’ll be so pissed, so annoyed”) was so keen to be included. The photo shows the four Metallica members perched on a riser in front of a drum kit. Ulrich is wearing a white, sleeveless shirt emblazoned with a drawing of an Absolut vodka bottle. He is grinning happily. By his side, James Hetfield and Kirk Hammett both appear to be in a similarly ebullient mood.

Cliff Burton is on the far left of the photograph. He’s got a black strip across his eyes (inserted by the printer) which is supposed to disguise his identity. Even so, it’s plainly obvious that it’s Burton – after all, who else would be sitting there?

What’s more, the blindfold doesn’t hide the fact that his face is wearing a very unfamiliar expression. I remember Ulrich saying that Burton was so appalled by his uncool behaviour when this photograph was taken that, as soon as he saw it, he ripped it to pieces and threw it away – he didn’t want Metallica’s fans to see him in such a compromising pose. But the offending and ripped photograph was rescued from the wastebasket and reassembled for use, without Burton’s knowledge, in the tour programme.

The repair job has been a good one. But studying the photograph at close quarters, I can see quite clearly how the cracks – the tear lines – in the reconstituted image converge to centre on Burton’s broken skull. And between the twin cascades of long, brown hair, I can definitely make out a jutting, defiant chin, some sunken cheekbones and – this is what Burton didn’t want anyone to see – a pair of puckered-up, hippy lips.

A lump the size of a cricket ball gets lodged in my throat. Through his shattered visage, Burton appears to be pursing his mouth to blow… a last kiss goodbye.

This feature was originally published in Classic Rock issue 56.