THINGS THAT HAPPENED IN A PARALLEL UNIVERSE,

PART ONE:

Imagine yourself as a teenage headbanger in San Francisco on 5 March 1983, stumbling into a sweaty, smoke-filled nightclub called The Stone to watch a hot new band.

Their blend of speeded-up Diamond Head riffage and Judas Priest-style technicality has brought them stacks of local attention, with fanzines spewing headlines about their forthcoming debut LP and the tape-trading underground in a frenzy about their demo tapes from the previous year.

Metallica, for it is they, were all aged only 19 and 20 at that early stage in their career, but they’d already been through some life-changing experiences. Formed in late 1981 when drummer Lars Ulrich and guitarist James Hetfield met through an ad in the free LA newspaper The Recycler (stop me if you’ve heard this before), the band soon acquired an image made up of denim, leather and acne and worked up some primitive thrash metal tunes.

They didn’t settle on a steady line-up for a while, ejecting their bass player Ron McGovney for being crap and then their second guitarist Dave Mustaine for being pissed a lot. Kirk Hammett, of San Francisco thrashers Exodus, stepped in on guitar and looked the part, all skinny trousers and Venom T-shirts – but McGovney’s replacement was anything but your standard 1983-style banger.

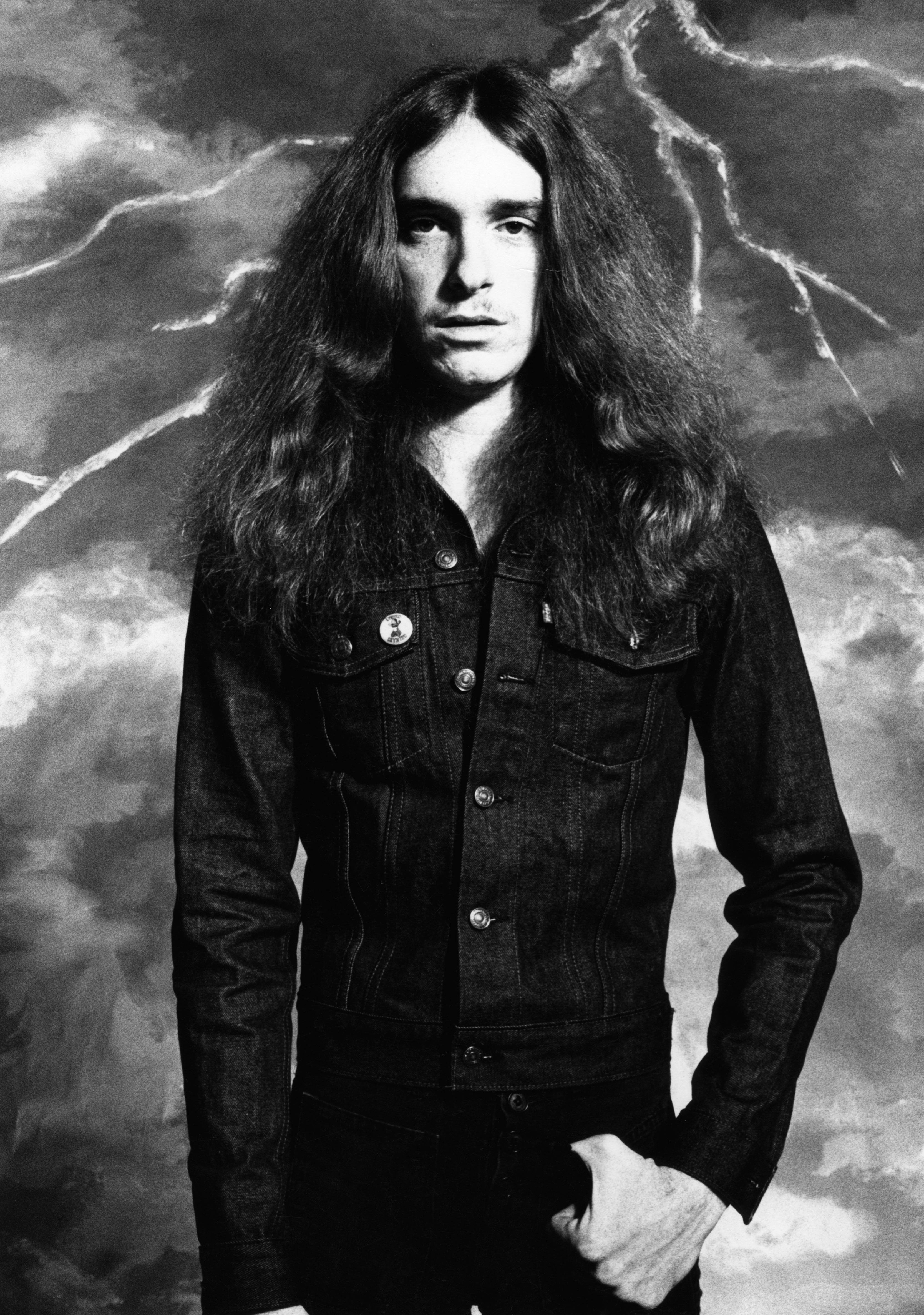

While you watched in open-mouthed awe as Metallica pumped out their fast, violent music, the guy on the bass whipped his head up and down like few others had done at the time. “The most head-banging bassist I ever saw”, is how Lars described Cliff Burton the first time he saw him play live, and James explained later that Cliff often had back problems due to the frantic, hunched-over moshing that he executed on stage. That was the first thing everyone noticed about Cliff.

Secondly, people raised their eyebrows at Cliff’s choice of nether garment. In 1982, as readers over 30 will recall with a shudder (and which those under 20 will recognise from their current wardrobe), your jeans had to be skin-tight or you were dead. Despite this, Burton favoured flappy old bell-bottoms, of the kind that had ceased to be fashionable in the late 1970s when the last of the hippies finally wised up and got a job in a bank. Cliff’s generously-proportioned strides were that terrible thing – a recently out-of-date clothing item. According to legend, everybody (including the rest of Metallica) laid into Cliff every single day about his terrible legwear – but he didn’t give a toss.

As Metallica producer Flemming Rasmussen told me: “Cliff was a really cool, really laid-back kind of guy. He was the only guy at the time wearing bell-bottoms, he liked them and he didn’t give a shit. He said that he’d just wait till they came back in style. All the guys gave him shit about them. He didn’t care.”

Most importantly, as you walked up to that San Francisco stage, you’d have noticed that Cliff was playing a crappy old Rickenbacker 4001 bass, which no metal bassist used back in 82 apart from Lemmy of Motörhead and Joey DeMaio of Manowar, both of whom are – revealingly – just a tad eccentric. What’s more, no-one played bass guitar like Cliff: at least no-one in a metal band. Ignoring the traditional supportive role played by the bass and whipping all over the fretboard like a man slapping bugs on a hot summer evening, Cliff executed dazzling runs and lightning-fast fills in, over and around the machine-like riffs delivered by Hetfield and Hammett.

It says an awful lot about Cliff that his heroes on the bass guitar were Black Sabbath’s Geezer Butler and Geddy Lee of progressive rockers Rush. Although Butler’s phenomenal skills on the bass matched Cliff’s, he was a less flamboyant player: it was his ability to make the bass complement a massive guitar riff which impressed Burton. As for Geddy (another Rickenbacker devotee), his bass-playing was completely nuts, taking in funk and jazz scales as well as the Western rock patterns that we all recognise. Nowadays bassists can be as experimental as you like, with Dream Theater’s John Myung, Les Claypool of Primus, Alex Webster of Cannibal Corpse and even Cliff’s ultimate replacement Rob Trujillo (an accomplished funk player) all making their mark – but a quarter of a century ago, nobody played heavy metal bass like Cliff Burton.

This incredible dexterity demanded exposure, and one of the highlights of Metallica’s set, back on that spring night in San Fran, was Cliff’s bass solo. He’d written a piece called (Anesthesia) Pulling Teeth, a solo that lasted over five minutes in length that normally came just before the band’s anthem, Whiplash. Using overdrive and distortion to give his bass sound sustain and texture, Cliff began Anesthesia with a series of triads that ascended a minor scale before devolving into a weird, almost folkie riff which eventually sank into a sea of feedback. Headbanging like a maniac even while playing the slower parts of the piece, Cliff left the crowd speechless – a red-haired kid in flares who shouldn’t have looked cool, but was somehow the coolest person you’d ever seen.

THINGS THAT HAPPENED IN A PARALLEL UNIVERSE, PART TWO:

Lars and James take Cliff to one side during the song-writing sessions for Master Of Puppets, saying, “Dude, we love your bass playing and all, but we’re gonna keep it simple this time round. Let us write the songs, OK? We want a one-word album title, too: maybe Load or something.”

By 1986, Metallica were at the top of their game, creatively if not yet commercially. 1983’s Kill ’Em All had been thrash metal’s first American salvo – we’ll give Venom the credit for inventing thrash in the first place. The Jump In The Fire and Creeping Death EPs and 1984’s breathtaking Ride The Lightning album had attracted the attention of the world’s moshers to Metallica, whose song-writing skills had taken a huge leap forward.

And not only their song-writing skills. As musicians, Hetfield, Ulrich and Hammett had evolved from merely kids who could play flash licks to world-class musicians of incredible precision and technical awareness. James in particular had developed a rhythm guitar technique which was millisecond-accurate, perfectly complementing Cliff’s crazy bass playing and allowing it plenty of breathing space. Just as Kill ’Em All had featured numerous solo moments for bass, including a long, ascending climb in the midsection of The Four Horsemen, Ride The Lightning featured a distorted bass solo in the intro of For Whom The Bell Tolls and a handful of awe-inspiring fills, such as the high-register pull-off just before the main riff of Creeping Death. Expectations were high for the band’s third album, and while everyone knew that Burton would contribute his pioneering bass tracks, few predicted that he would take his place as one of Metallica’s primary songwriters.

Sandwiched between the dark Leper Messiah and the incredibly powerful thrash metal anthem Damage, Inc., the eight-minute instrumental track Orion is that rare thing: an absolutely unclassifiable song. Lars and James composed chunks of it, but it’s immediately apparent that the track was masterminded by Cliff, opening with a fade-in composed of a silky, treated bass chord sequence.

In 1992, Lars explained how Burton’s musical awareness had made a profound impact on his and James’ musical education, saying: “Cliff was responsible for a lot of the things that happened between Kill ’Em All and Ride The Lightning. He really exposed me and James to a whole new musical horizon of harmonies and melodies, just a whole new kind of thing, and obviously that’s something that greatly influenced our song-writing abilities on Master Of Puppets… the whole way that me and James write songs together, I mean, that was shaped when Cliff was in the band, and was very much shaped around Cliff’s musical input; the way he really taught us about harmonies and melodies and stuff.” James added: “Cliff brought certain melodies into our music which he’d learned at school during his classical training. He knew how those harmonies function.”

Now, imagine that Cliff hadn’t been allowed to write those parts, teach what he knew to Lars and James and thereby change Metallica’s output forever. There’s more to it than just bass, mind: Burton had a unique approach to music, placing his beloved classical theory on an equal footing with the most stripped-down music of all, hardcore punk. Famous for his Misfits T-shirts and Samhain tattoo, as well as his commandeering of Metallica’s tour bus stereo to play endless Discharge albums, Cliff brought a blend of incredible musical intricacy and malevolent, bludgeoning ugliness to the band, in his education of his fellow musicians as well as in his own bass playing. Perhaps that’s the secret of world-dominating metal albums like Master Of Puppets: they’re intricate and melodic enough to make you sing their songs to your dying day – but they’re also so sonically destructive that they scare the bejesus out of the non-metal-loving masses.

Of course, in reality Cliff was on fire during the Puppets sessions, coming up with his masterpiece Orion and those two intricate song intros. If James and Lars had persuaded him not to exercise his creative abilities on the album, Puppets would have been more mainstream, less extravagant, more digestible and less rewarding. The band still had hunger in abundance, of course: Puppets wouldn’t have been S&M or anything. But it would have been a weak version of the album that metalheads know and love to an almost unhealthy degree. That’s how good Cliff was.

THINGS THAT HAPPENED IN A PARALLEL UNIVERSE, PART THREE:

Cliff survived the fatal coach crash, because the glass of the window next to him was made of a tougher material and didn’t break when he smashed into it. He crawled out of the bus with concussion and bruises, swearing and coughing but basically intact.

For Cliff Burton, 1986 was going to be the year when he would push his band to the next stage, investing them with still more of his musical talent. Photographer Ross Halfin, who spent extended periods of time with Metallica, explained: “The thing that people miss is that at the beginning it was very much Cliff Burton’s band. He very much ran the band and after 1986 Lars took it over. James didn’t really have a lot to do with it, it was all very much Cliff.”

On its release in March 1986, Master Of Puppets made a seismic impact and eventually went six times platinum. The band then embarked on a crucial tour supporting Ozzy Osbourne, before heading off on their own headlining jaunt through Europe with Anthrax in support. The Damage Inc. tour has gone down in history as the best thrash metal bill ever assembled: both Metallica and Anthrax were on peak form, levelling audiences from Kansas in March to Sweden in September.

That Stockholm gig, played on 26 September, was Cliff’s last. On a mountain road near the town of Dörarp, Metallica’s tourbus went into a skid which the driver was unable to correct and toppled onto its side. Although the vehicle wasn’t moving particularly fast at the time, Cliff was ejected halfway through a window next to the bunk in which he was sleeping and crushed to death underneath the bus. The driver claimed that the bus had hit black ice; Hetfield accused him of being drunk; the police initially thought the driver might have fallen asleep at the wheel. In the end no-one really knew what had happened – only that one of the most gifted musicians of a generation was dead.

So let’s pretend that Cliff survived the crash. What would he have gone on to do? Would Metallica’s career arc – which included one more progressive album, …And Justice For All, the stripped-down, globe-shattering Black Album and then a sequence of more or less depressing releases until the present day – have been altered in any way? Quite possibly. Martin Hooker of the Dreamcatcher label (and once of Metallica’s UK distributor Music For Nations) thinks that Burton might have taken a simpler route, saying: “If Cliff was alive today he’d be playing in a band like Electric Wizard. Stoner rock could have been invented for him!”

Or perhaps he would have combined his avant-garde and extreme metal bass styles in a progressive death metal band like Cynic or Atheist; maybe he would have stuck with Metallica through their radio-friendly years; possibly he would have become the session player to end all session players. It’s unlikely, however, that he would have endured the endless therapy with counsellor Phil Towle that made the St. Anger era such a pain in the arse. A man like Cliff could have done literally anything he wanted…

Unfortunately, there is no parallel universe. This is the universe we’re stuck with, so raise your glass to Cliff, load Metallica’s new album into your CD player when it comes – and don’t mourn his premature passing. Instead, be grateful that he was with us at all. The world of music is much richer thanks to him: how many of us will be able to make the same claim when our time comes?

This article originally appeared in Metal Hammer #21.

For more on Metallica’s legendary bass player, then click on the link below.