When 20-year-old Luis Enrique Delgado – ‘Papo’ to his friends and family – heard about the first Ciudad Metal festival and all the bands that would be playing there, nothing could stop him hitchhiking the 275 miles from his home in the Cuban city of Pinar del Río to Santa Clara, where the gig was to be held.

This was 1990, and it was a surprise that the festival had been approved. Maybe the authoritarian Communist Party that ruled Cuba saw the request from the local chapter of the national youth arts organisation as a benign plan to bring culture to the masses. And Santa Clara, located near the centre of the island, had historical significance – it was where Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara’s revolutionary guerillas had won victory in 1958, changing the course of Cuba’s history forever.

Papo himself had endured a hard childhood. He was regularly beaten by his alcoholic father, as were his mother and younger brother. He found solace in rock and metal – Led Zeppelin at first, then Metallica, then Kreator, then whatever he could get his hands on.

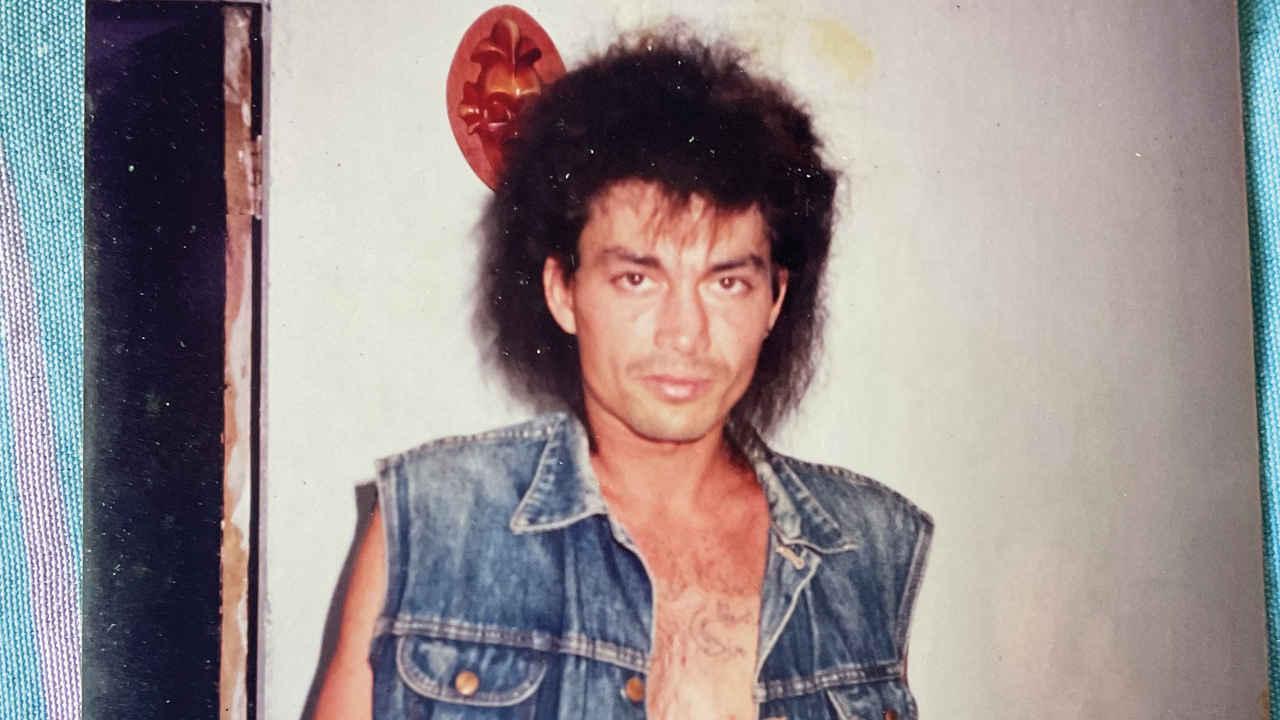

By his late teens, Papo had got his ears pierced, was wearing studded bracelets, had let his hair grow long and even given himself homemade tattoos, receiving unwanted attention from the police for his troubles. By 20, he had served almost two years in prison for petty offences and unpaid fines.

On the first day of June, 1990, Papo made it to Ciudad Metal – ‘Metal City’ – along with 2,000 other metal fans. On the final night of the festival, as local heroes Zeus thrashed out their anthem Violento Metrobús, members of the crowd stormed the stage and began stagediving. Seats in the front were torn open and the stuffing ripped out of the cushions.

The police, truncheons swinging, cleared the theatre. In the street, Papo found himself at the head of a pack of fans, fists pumping. That was the point, there and then, that he discovered what he was: a leader. He wanted to take the power back for people like himself. To show them they could take matters into their own hands, as he had done.

Papo had set out for Ciudad Metal with an idea forming. There were rumours circulating of a shocking sacrifice some hardcore metal fans – nicknamed frikis, a phonetic translation of the English word ‘freaks’ - were making. These kids were deliberately injecting themselves with HIV, the virus that was ravaging parts of the island’s population.

Cuban leader Fidel Castro had introduced a new slogan: Patria o muerte, ‘Fatherland or death’. Since it looked to los frikis like the authorities had rejected them, they’d show the Cuban government their choice while remaining defiantly in their face: death over fatherland. And Papo Delgado would soon be at the centre of this new, and fatal, revolution.

By the time Ciudad Metal took place, Fidel Castro had been in power in Cuba for 31 years – first as Prime Minister and then as President. Castro aligned his country politically and financially with the Communist USSR in a struggle against a common enemy: the USA.

Technology took a decade longer to reach Cuba than anywhere in the West. In the mid-80s, with the arrival of cheap Soviet radios and cassette players, two decades’ worth of rock music hit the island all at once.

The teenage Papo Delgado fell hard for metal, wearing out bootlegged Motörhead tapes and hoarding the few metal magazines that found their way through cracks in the economic blockade set up by the US.

An earlier generation of rock fans in the late 70s and early 80s had been dubbed ‘frikis’, but by the end of the ’80s the name was up for grabs. A rising generation of metal fans grabbed it hardest. They shirked military service and hung out in city parks, they played their music loud and forged prescriptions for pills, they hitchhiked between cities and towns and lived off whatever they could beg, scrape or steal. Papo was puro friki, and proud of it.

The authorities hated los frikis. Fidel Castro’s brother Raul had created a new branch of the national police force to address what he and other hard-liners saw as a new threat to Revolutionary conformity: teenagers like Papo. When a friki was arrested, they might be beaten, pushed up against a wall with a bayonet or have their hair cut with a knife. If they tried to talk back, it was worse. The first time Papo went to jail, it was for stealing a tin of food. The second was for the fines that had multiplied for being a friki.

Niurka Rojas Fuentes was a country girl from Guane, two hours by train from Pinar del Río, and had moved to the city to train as a teacher at college. She would see frikis scattered throughout the streets and parks, but she had nothing to do with them until, in her fourth year in school, she met Papo.

He was cocky, charismatic and all the other frikis looked up to him. They’d given him a nickname, la Bala, or ‘Bullets’, the slang for pills (Secobarbital, Dexedrine, Haldol), which Papo obtained with the aid of a stolen prescription pad. Niurka and Papo began seeing each other.

A few days into their relationship, Papo told Niurka he was hitchhiking to the Ciudad Metal festival. On the road back, he stopped off to meet his childhood friend Juan Miguel, who had contracted HIV and had been admitted to one of the 14 sanatoriums set up in the mid-80s by the national medical service to combat the new virus. It was there, on June 4, 1990, that Papo Delgado injected himself with HIV.

There was a phrase among los frikis for the choice kids like Papo were making: ‘La vola.’ The Oath. To take la vola, they sought out somebody who was HIV-positive to procure their blood, which they would then inject into their own veins.

“I gave myself AIDS – and many others like me – because we were the most persecuted class in the entire country,” Papo said. “The police fell hardest on us. All the laws were against us. It was a level of discrimination completely without democracy.”

But that wasn’t the sole reason Papo injected himself. Being HIV+ meant he could avoid being sent back to prison. Instead, it was a ticket to el sanatorio – the sanatorium. Life in the sanatorium shielded quarantined patients from the food shortages and power outages of what Fidel had taken to calling the “Special Period”, a euphemism for the tailspin that hit the Cuban economy as the USSR began to crumble at the end of the 1980s.

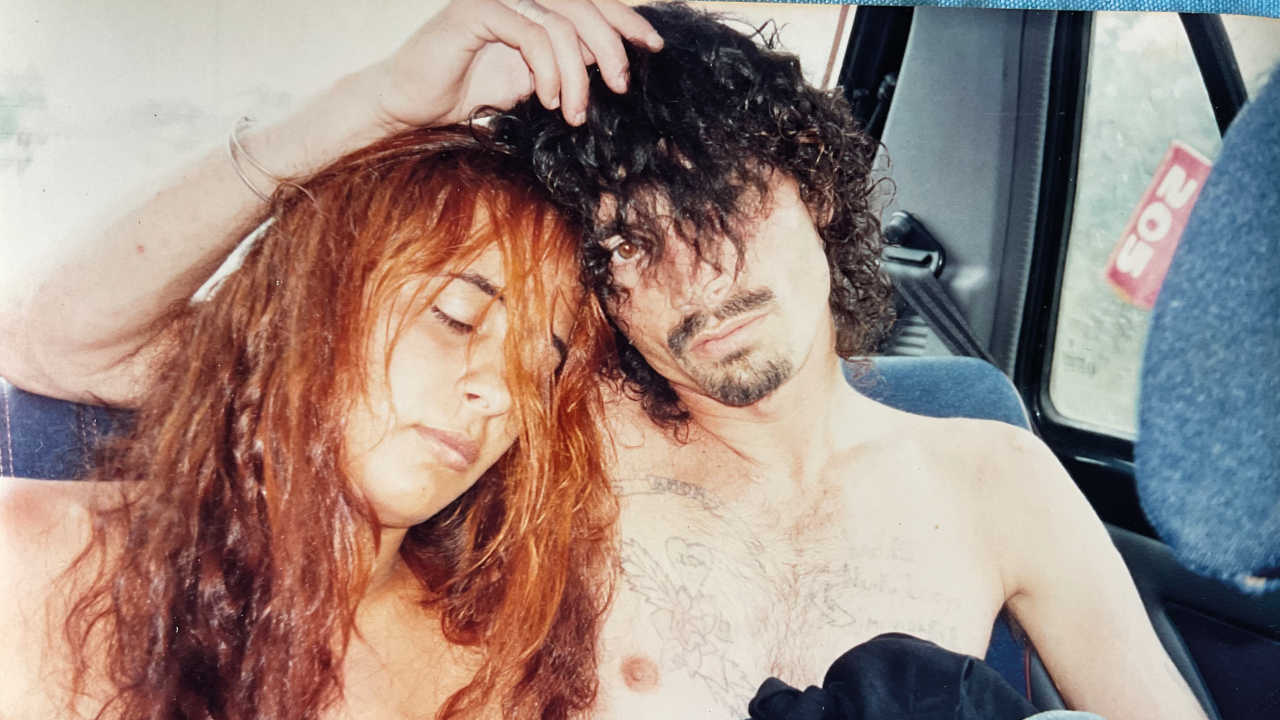

When Papo returned from Ciudad Metal, Niurka was the first person he told what he’d done. He said he would understand if she chose to no longer be with him, but any doubt in his own mind had been abolished. It was a hard blow to Niurka, but she had seen how the police treated young people like him.

Five weeks after Papo returned from Ciudad Metal, less than a month after Niurka’s 19th birthday, they married at a government office. Niurka took her own version of the Oath. She did not want to inject, but she and Papo knowingly had unprotected sex so she could contract HIV and be with him at the sanatorium.

For a brief time, the sanatorium was a kind of metal heaven for the pair. They had a private cinderblock cabina and could play their music as loud as they wanted. They were allowed out once a week, under close supervision, to go to the beach or the nearby Guamá River.

Papo started a metal band, Metamorfosis, with three other frikis at the sanatorium. They rehearsed his original songs like El SIDA nos acecha y un Partido aparte también – ‘AIDS Is Stalking Us, and So Are The Commies’.

Soon, the news of what Papo and a few other frikis had started spread like wildfire across the island, largely by word-of-mouth at concerts in the cultural centre and clubs that were emerging as homes to rock and metal. Before long, hundreds of young metalheads across the island had heard of Papo la Bala, with many of them following his example by taking the Oath. Niurka later said she personally knew of 140 frikis who had self-injected with the HIV virus; she guessed there were 800-900 in total across Cuba.

For los frikis, this was the ultimate ‘fuck you’ to Fidel Castro and his government. It was a desperate demonstration, shocking in its stark nihilism and self-destructive simplicity. In the early 90s, before the availability of antiretroviral drugs, it was also a slow, certain suicide.

Many young frikis, ignorant of the immutability of an act that took only an instant, did not believe the Oath was final. Heartbreakingly, some believed Fidel Castro already had a cure, and was waiting for the right time to make a big deal out of announcing it. But after five months in the sanatorium, the first one died: Papo’s best friend, El Flaco. Soon there were many frikis in a serious condition and two or three deaths a day.

At the time, a couple of newspapers reported on the plight of los frikis. When the self-injected started dying, young people stopped injecting. The core identity of ‘friki’ reverted back to the regular metalheads, who reappropriated the identity for the spirit of rebellion it invoked. They stopped short of taking the Oath, but for the ones who had already taken it, there was no cure.

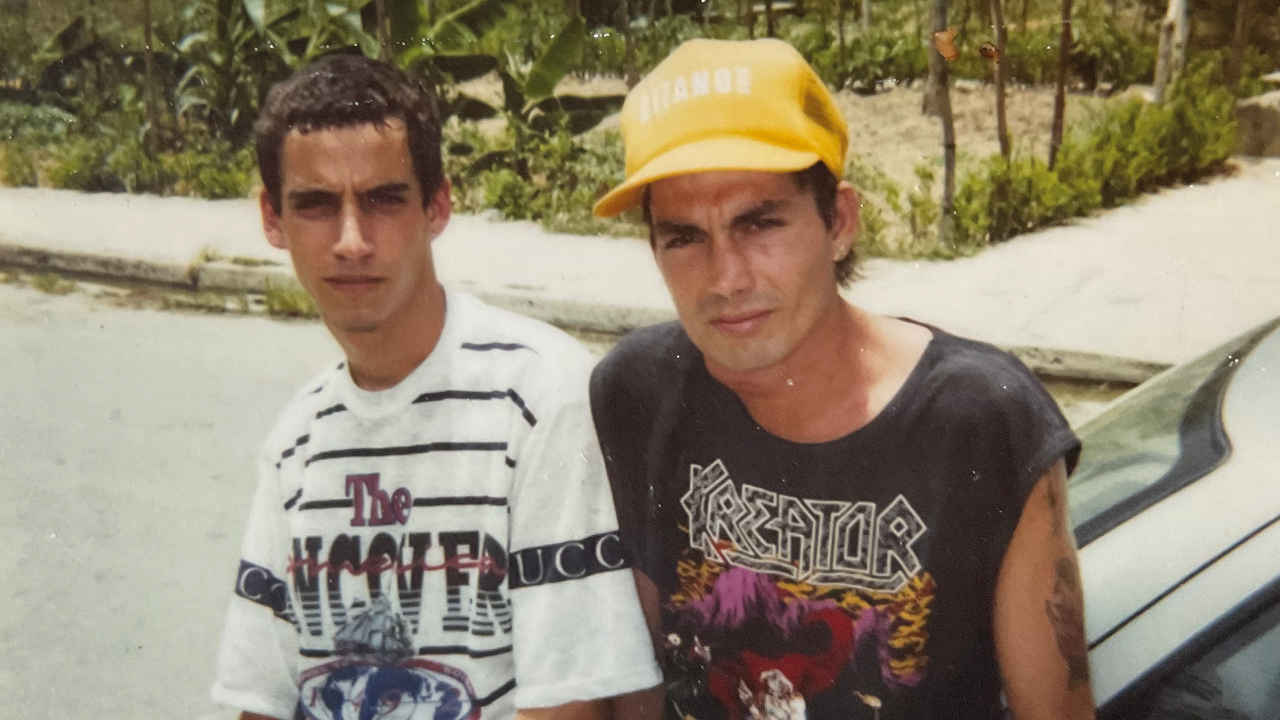

I met Papo on the first of several trips I took to Cuba in the 90s. We were the same age, our birthdays just 11 days apart. My parents had left the island for the United States following the Revolution, and he wanted to know what it was like to grow up Cuban in the USA.

When it came to taking the Oath, he didn’t harbour any personal regrets. “I am going to stick it out,” Papo told me. “I’m determined to see it through to the end.” Still, he seemed uncomfortable with how many frightened young people had invoked his name as the inspiration for their own self-injection. The burden of becoming a spokesperson, and of the increasing fear and hopelessness in the eyes of the young frikis who looked up to him, was something he never reconciled with.

On July 15, 1995, after four years of progressive illness, Papo Delgado died of cerebral cryptococcosis – a parasitic fungus that ate away at his brain. Niurka would later outline the details of his death: how he was admitted to the hospital with a serious infection, confused, hallucinating and in great pain. The following morning, he briefly became clear-headed and told her to take care of some outstanding affairs. At 10am he went into cardiac arrest. Niurka gave him mouth to mouth, but by the time the doctor had arrived, Papo was dead. He was one week shy of his 26th birthday.

Remarkably, Niurka is still alive. She had been a slow progressor, a rare AIDS patient who had been able to hold on long enough for antiretroviral drugs to arrive. Today, Niurka’s immune system is so compromised that simple skin irritations can turn into life-threatening lesions. Lately, antibiotics have been hard to come by. When I called her by phone to interview her for this piece, she choked back sobs. “All the others from that time have died,” she said.

Years after Papo’s death, I was involved in an interview with a prominent Cuban priest who was friends with Fidel Castro. The priest said that he had told Castro what los frikis were doing to themselves. He claimed that the leader listened, then said: “I had no idea. I believe you and I can’t even believe it.”

Is it possible that when Castro learned of los frikis and la vola, it set wheels in motion that allowed a more tolerant attitude towards metalheads and ‘miscreants’ that took hold in Cuban society at the turn of the millennium? Perhaps. By 2007, the government had allowed the formation of the Agencia Cubana de Rock, which promotes rock and metal concerts and festivals in venues across the island.

Ciudad Metal returned in 2000, a decade after it was last held. This year, the festival runs from November 29 to December 3. More than 20 bands – among them Tendencia, Blinder, Combat Noise and Night Of Terror – keep the original spirit alive through a PA system that booms over every city block with a din reminiscent of Soviet-era bullhorns. Nowadays at Ciudad Metal, the cops smile and chat amiably with kids dressed as outrageously as Papo once did.

We will never know for sure, but Papo’s idea and the resulting tragedy may have been responsible for turning back the systemic persecution of metal fans and young people, sparing thousands who came of age in his wake.

I last saw Papo less than a year before his death. I travelled with a video camera and kept the lens trained on him while there was time. “Tell the world our story,” he said. “It would be better accompanied by photos of frikis, so a magazine would be best.” I still see his eyes, penetrating like bullets through the back of my mind: “Make sure it’s metal.”