"I understand that you have to ask a question like that, but I don’t want to talk about rumours as much as I want to talk about music.”

Marilyn Manson is speaking down a phone line between Los Angeles and London.

So is there no truth in it, I ask?

“Like I said. I won’t qualify it with an answer.”

It’s fair to say that our conversation is going downhill rapidly.

So you only want to talk about the new album? You don’t want to talk about the allegations against you?

“There’s no allegations against me, and I’m not going to talk about it. Rumours…”

There’s an empty, black silence. Marilyn Manson – one of modern music’s most articulate figures and a man who never ducks a question – has hung up.

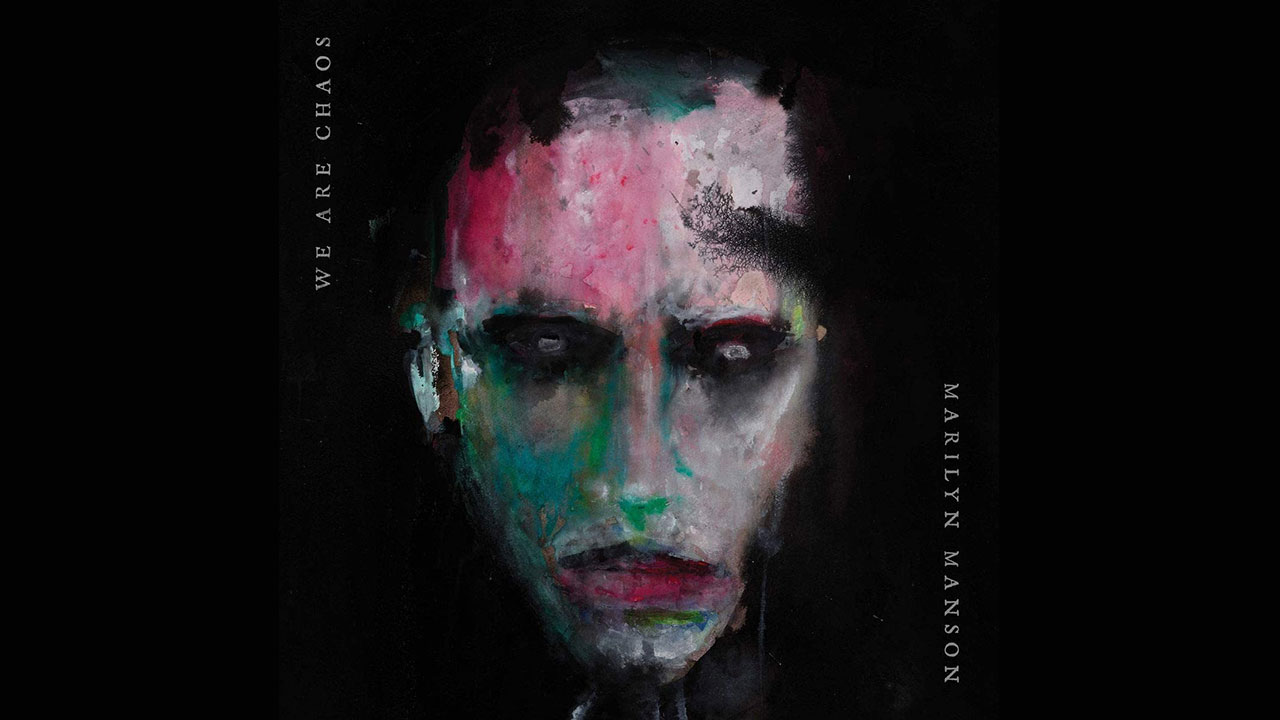

This wasn’t the plan. The plan was to talk to him about his new album, We Are Chaos, and his place in the era of #MeToo and Cancel Culture – a time when the more toxic aspects of old-school rock’n’roll behaviour increasingly won’t wash.

We never get as far as that. The reason: I have ventured into an area that Manson clearly does not want to engage with. It turns out that the way to silence Marilyn Manson is to say three simple words: Evan Rachel Wood.

It’s just gone 11pm in California and just after 7am in the UK when Marilyn Manson calls. These aren’t common hours for interviews, even among rock stars. But Manson isn’t so much a night owl as someone who lives in a permanent state of timelessness, curtains closed, shutting out not just the light but the world too.

He’s charm personified. Off the bat, he asks if we have spoken before. We have, twice: once briefly at an aftershow party following his first UK gig in 1996 and once in similar late night/early morning circumstances around the time of 2003’s The Golden Age Of Grotesque. On both occasions, he was funny and insightful, the smartest person in the conversation by a long stretch.

He’s no less smart today, though his answers are longer and more rambling than I remember. A jokey question about how he’s spent the last six months – has he learned to make sourdough bread or has it been one long absinthe and crystal meth isolation party? – prompts a four-minute response that begins with Manson emphasising that “heroin, crystal meth, things that are a one-way road to destruction, have never been my choice in life”, before taking a lengthy detour to recap the holy trinity of albums he made during his late 90s/early 00s imperial period (Antichrist Superstar, Mechanical Animals, Holy Wood), and, finally, alighting on the psychological machinery that drives We Are Chaos.

“It hasn’t been until now, with We Are Chaos, that I’ve felt it’s something that’s true to my heart, because I wasn’t afraid to show all of the pores of my face, the eyelashes, the cavities of my teeth, the cuts on my chest,” he concludes. “All of the elements that have made me who I am. We’re all built on our experiences, and made stronger by them, not weakened.”

As the conversation proceeds, it becomes clear that this is a pattern: a question is followed by a long-verging-on-the-verbose answer that occasionally veers off on obscure, opaque tangents before returning to the main thread. Attempts to cut in or steer him onto other topics don’t work. Marilyn Manson is ultimately talking about what he wants to talk about, which is his music, his art and his new record.

This is fair enough. We Are Chaos is undeniably a top-tier Manson album. It continues the artistic resurgence that began with 2015’s The Pale Emperor and carried on through 2017’s Heaven Upside Down. He heaps credit on Shooter Jennings, son of late outlaw country icon Waylon Jennings, and Manson’s current chief collaborator and co-producer. “Sometimes I will think faster than a lot of people can keep up with, but Shooter would do something before I even finished my sentence,” he says.

Whether We Are Chaos restores Manson to the place he once occupied in the cultural landscape is another matter. For a while, back in the late 90s, Manson was at the front and centre of things. He wasn’t just making the conversation, he was the conversation – newspapers wrote about him, protesters lined up outside his gigs, the religious right called for him to be banned, everyone from Eminem to one-hit wonders The New Radicals dropped his name into their songs. But it hasn’t felt like that for a while. Is that fair to say?

“Fair enough,” he says reasonably. “I never felt I was [the conversation] at the time. I knew that I was doing things that obviously weren’t going to make the entire world hold hands and sing a Pepsi commercial or Kumbaya. I wasn’t trying to be a hero, I was trying to be me.”

“I wasn’t trying to be a hero…” He sounds sincere when he says that. But whether he intended it or not, that’s precisely what Marilyn Manson was.

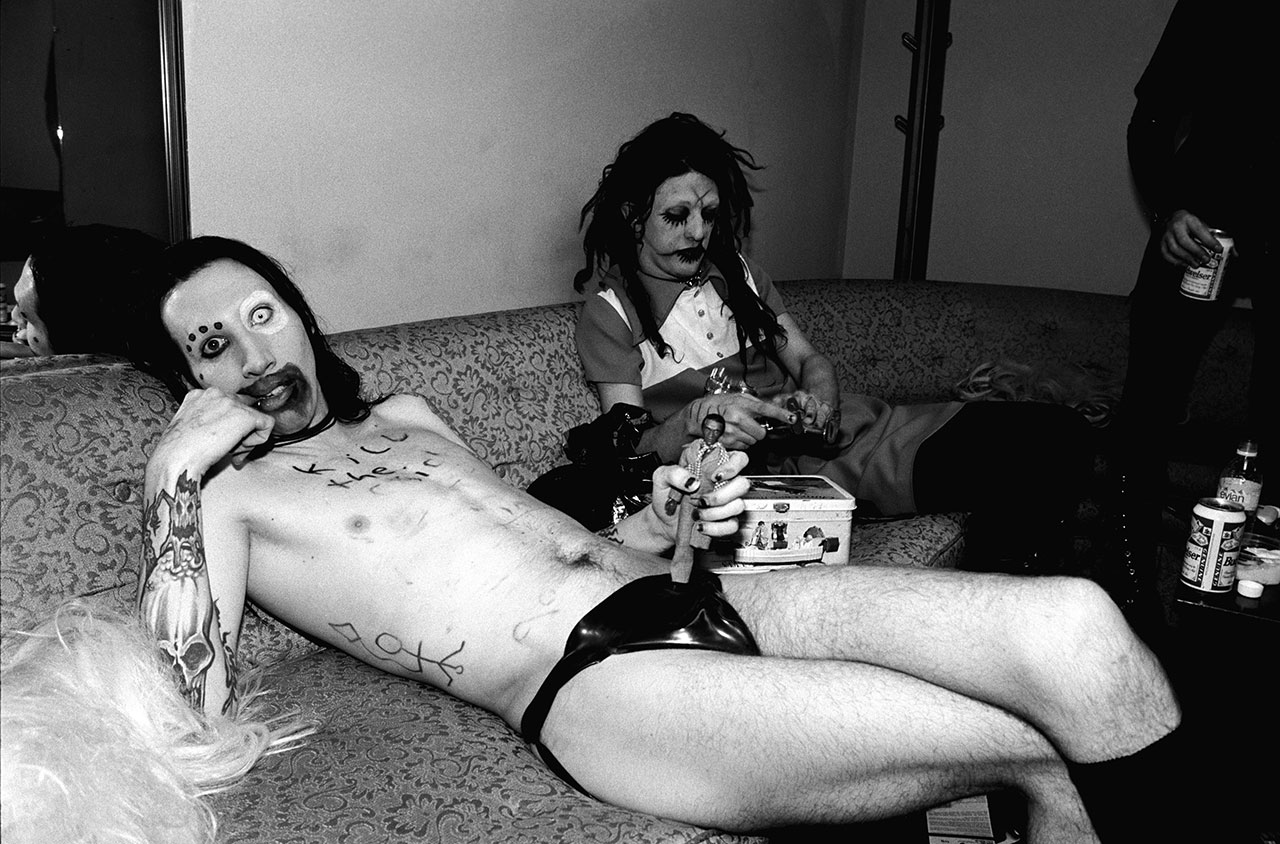

The Marilyn Manson mythology emerged fully formed in the mid-90s. Here was the latest folk devil to plague God-fearing America: a deviant, a drug fiend, a corrupter of the nation’s youth. This was a man who was said to have smoked human bones (true) and had one of his ribs removed so he could perform fellatio on himself (not true).

“I was never trying to be controversial or shocking,” he says now of his notoriety circa Antichrist Superstar, “but I was aware that the key to upheaval is hitting somebody directly in the face, putting a mirror to them and saying, ‘This is you.’” His aim was “to shake things up: religion, Christianity, basically. More than that, to make people see that politics and religion are secondary to art.”

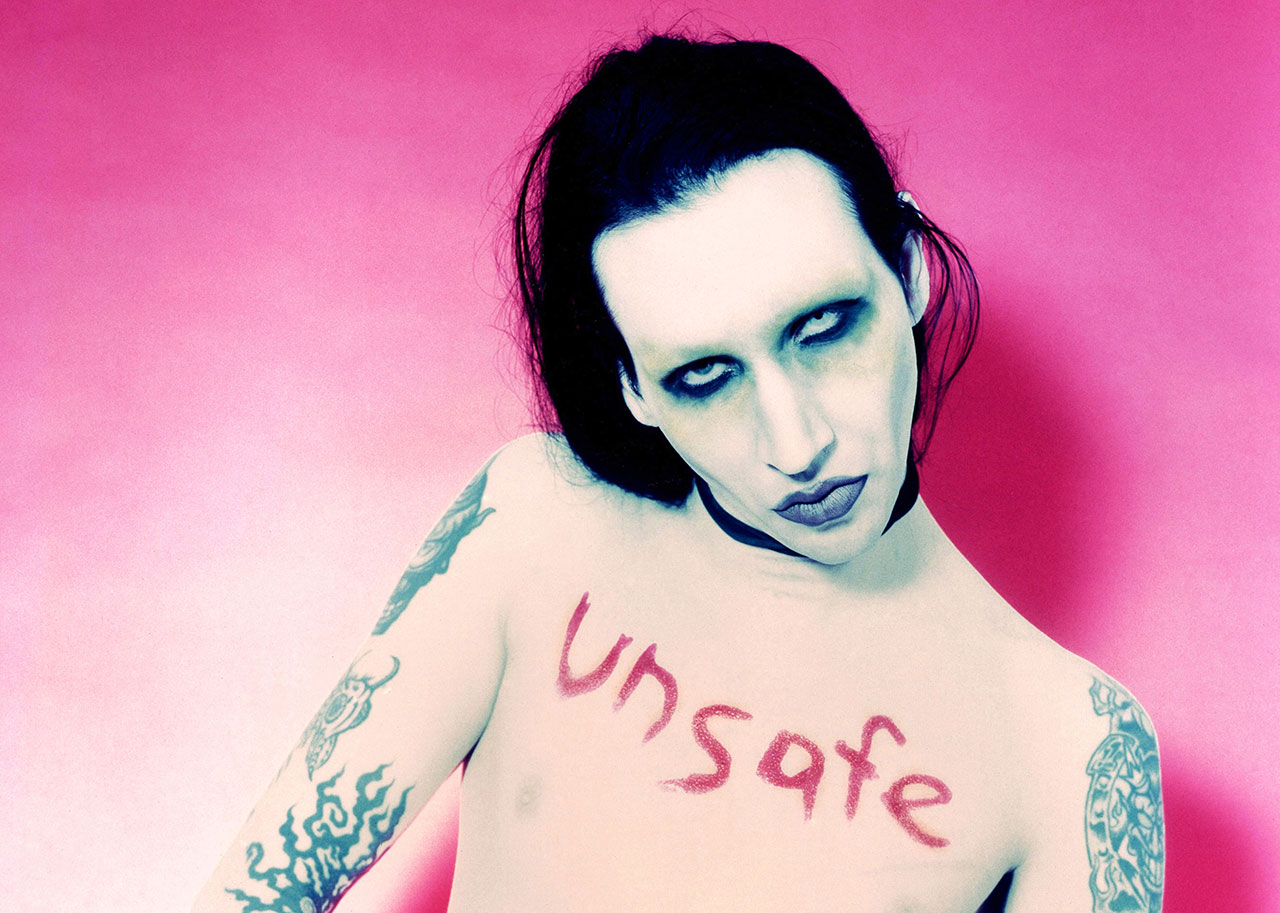

The controversy that surrounded him overshadowed just how revolutionary he really was. This was a world away from metal’s play-acting rebellion. An outsider with a Christian school education, he made it OK to be different, challenging people to think for themselves and be themselves.

By taking on the bullies – church, government, school – he empowered the powerless to do the same. Manson wasn’t an amoral demon but an unlikely moral compass, a rational voice in an irrational world – something proven beyond doubt after sections of the media unsuccessfully tried to pin the blame on him for the 1999 massacre at Columbine High School. “I thought, ‘Instead of feeling as if everything in art is misunderstood, confusion is the way you change culture.’ It’s important,” he says of the latter event, which inspired 2000’s Holy Wood (In The Shadow Of The Valley Of Death) (“My pride and joy,” he declares today).

For all that, he still played the role of rock star, to the point of cliché. His 1998 autobiography, The Long Hard Road Out Of Hell, made no secret of his drug use, or the groupies that surrounded the band. In one memorable section of the book, a deaf girl named Alyssa joins Manson in the studio. By the end of the passage, she has been covered in cold meats, had sex with keyboard player Madonna Wayne Gacy and been urinated on by Manson and bassist Twiggy Ramirez. In Manson’s telling, she wasn’t being exploited. “I think she, too, found it to be art and was having a good time,” he said.

Like many newly minted rock star celebrities before him, he began moving in circles that were previously closed off to him. He dated actor and future #MeToo activist Rose McGowan, married (and split from) burlesque artist Dita Von Teese and later began a relationship with rising Hollywood star Evan Rachel Wood.

Wood was 18 years old when they met; Manson was 36. According to Wood in a 2016 interview with Rolling Stone, the narrative of ‘big bad rock star corrupting innocent young starlet’ wasn’t accurate. “I met somebody that promised freedom and expression and no judgments,” she said. “And I was craving danger and excitement.”

Still, their relationship was complex and combustible. When they temporarily split up at the end of 2008, Manson effectively admitted to harassing her on the telephone.

“And every time I called her that day [Christmas Day 2008] – I called 158 times – I took a razorblade and I cut myself on my face or on my hands,” he told Spin magazine in 2009. In the same interview, he proclaimed that the song I Want To Kill You Like They Do In The Movies, from his 2009 album The High End Of Low, “is about my fantasies. I have fantasies every day about smashing her skull in with a sledgehammer.” (By early 2010, Manson and Wood had reconciled and got engaged, but they later split up and did not get married.)

Words and actions aren’t the same thing, of course, but still: if a friend told you they were aggressively stalking and harassing an ex-lover or fantasising about taking a sledgehammer to their skull, you’d wonder about the nature of their relationship.

But Manson got a free pass. He was allowed to behave like that. He was an artist. He was a rock star.

Once, a rock star’s job was clear cut: they were there to entertain us, but also to live out our fantasies for us. Fame, money, drugs, sex – harmless, responsibility-free fun, with no one to answer to. Except when it wasn’t.

Things have changed in recent years. Male musicians and members of the music industry are being asked to answer allegations that range from the toxic to the criminal. This year, former Of Mice & Men singer Austin Carlile was accused of sexual assault by multiple women (he denied the allegations), while allegations of rape, sexual harassment and abusive behaviour levelled on social media at Holy Roar Records founder Alex Fitzpatrick prompted an exodus of bands from the label and Fitzpatrick’s own resignation (“These allegations are false and I am doing everything I can to clear my name,” he said in a statement).

This new reality has intruded into Manson’s world. In 2017, his then-bassist and on/off right-hand man Twiggy Ramirez (real name: Jeordie White) was accused by his ex-girlfriend, Jack Off Jill singer Jessicka Addams, of raping and abusing her in the 1990s, during Ramirez’s original stint in the band.

A week after Addams made her accusations on Facebook, Manson fired Ramirez. “I have decided to part ways with Jeordie White as a member of Marilyn Manson,” said Manson in a statement. “He will be replaced for the upcoming tour. I wish him well.”

Ramirez himself neither confirmed nor denied the allegations, saying: “I do not condone non-consensual sex of any kind… If I have caused anyone pain, I apologise and truly regret it.”

Manson himself addressed the situation a few months later. “I did not divorce Twiggy as a friend or brother, because I still care about him greatly,” he told Kerrang! magazine, in their Christmas 2017 issue.

This accountability is long overdue across the board. But it raises the question: what’s the job of the rock star today?

“It’s hard to say,” replies Manson. What follows is another long and confusing answer that takes in his aspirations as a 15-year-old (“The basic concept was, ‘Maybe I’ll meet a girl, that would be cool’”), the difficulty people have in distinguishing between Brian Warner and Marilyn Manson (“I would always say, ‘They’re just names’”) and, inevitably, his new album (“When I did this record, I did, for the first time, the painting for the album cover”). In fairness, he does give an answer to the question – “The job of a rock star is to entertain people” – but it’s buried deep in his response and so mundane I don’t hear it until I play back the recording.

Speaking recently to a journalist from Classic Rock magazine, Manson was asked what scared him. “I’m scared of the possibility that art – and people’s freedom of speech – is going to be choked,” he said, referring to a “mob rules mentality”. Given the things he’s said and done over the years, real and perceived, is he surprised he’s never been ‘cancelled’?

“I don’t think…” he begins to say, then stops. “I think that’s not a subject that’s even worth addressing, because it’s something that… To answer your question, you can go back to the very first thing I said about Antichrist Superstar/Columbine. That answers your question.” He repeats himself. “That answers your question.”

He’s referring to his comment that “confusion is the way you change culture”. That maybe artists shouldn’t have to explain themselves, but let their art do the talking. But there are some things we’d like to talk to him about.

In April 2019, Evan Rachel Wood – at the time starring in the TV show Westworld – appeared in front of the California Senate Public Safety Committee in support of the Phoenix Act, a proposed law that called for an extension of the statute of limitations on domestic violence crimes from three years to 10 years.

As part of videotaped testimony, a visibly distraught Wood gave details of an abusive relationship she had been in for several years with a man she met in her late teens. She told how the man, who had “hidden a terrible drug and alcohol problem from me”, cut her off from her friends and family and threatened her during bouts of jealousy-fuelled rage. She detailed how the man had forced her to partake in acts of “fear, pain, torture and humiliation”, which he would videotape and threaten to leak.

There was much more to her harrowing testimony, including instances of beatings and rape, plus death threats against her and her friends. The picture she painted was one of mental and physical abuse, resulting in “complex PTSD, including disassociation, panic attacks, night terrors, agoraphobia, impulse control, chronic pain in my body, among other symptoms.”

This wasn’t the first time Wood had spoken publicly about the abuse she had suffered during a previous relationship. In February 2018, she gave similar testimony to a House Judiciary Subcommittee.

Wood didn’t name her abuser in either hearing, though some connected her testimony with Manson. In a March 2018 article headlined ‘Why Is Nobody Talking About Marilyn Manson’s ‘Fantasy’ of Killing Evan Rachel Wood?’ in reference to Manson’s 2009 Spin interview, US magazine Glamour pointed out that the pair’s relationship began when she was 18 (in Wood’s 2019 testimony, she confirmed the abusive relationship she was referring to was underway when she was 18 years old).

It quoted a tweet from the actor and activist Patricia Arquette, that referred back to the same 2009 interview. “Marilyn Manson Cutting himself 158 x’s when he called Evan Rachel Wood after breakup it’s not [LOVEHEART EMOJI] it’s abuse,” the True Romance star had tweeted the day before.

Marilyn Manson Cutting himself 158 x's when he called Evan Rachel Wood after breakup it's not ❤️ it's abuse.. @SPINMarch 1, 2018

In 2019, Wood shared a photo on Instagram of a 2010 shoot for Elle magazine. “The day of this photoshoot, I was so weakened by an abusive relationship,” she wrote in the caption. “I was emaciated, severely depressed, and could barely stand. I fell into a pool of tears and was sent home for the day.” In a second photograph shared at the same time, she wrote: “[Two] years into my abusive relationship I resorted to self harm. When my abuser would threaten or attack me, I cut my wrist as a way to disarm him,” she wrote. “It only made the abuse stop temporarily. At that point I was desperate to stop the abuse and I was too terrified to leave.”

During the 2019 hearing, another of Manson’s former partners, the British-born Game Of Thrones actor Esmé Bianco, also gave testimony about an abusive relationship she had been in during an unspecified period of time.

Neither Bianco nor Wood has named their abuser, and there’s no suggestion either was talking about Manson. But speaking to him now, it seems wrong not to address Wood’s testimony specifically and the #MeToo movement in general. After all, if Manson had nothing to do with Evan Rachel Wood’s testimony, then the people putting two and two together online are way off and he’s being unfairly tried by social media. It must be frustrating, and terrifying, to be judged like that.

What did he think when he heard her say it? There’s a pause.

“This is where I head out to the photoshoot, because I talk about music,” he says. “I’m not here to talk about rumours.”

Is it not worth addressing?

“I understand that you have to ask a question like that, but I don’t want to talk about rumours as much as I want to talk about music.”

So is there no truth in it?

“Like I said, I won’t qualify it with an answer.”

Manson doesn’t sound angry or exasperated when he says this. There’s a calmness in his voice. But he’s clearly not engaging with what I want to talk about. I try another question – does he still feel like a transgressive artist? – but we end up talking over each other.

“Nah,” he’s saying, “I’m just saying you’re not going to get a response from that. It’s only because it’s not something I’m gonna respond to, ’cos it’s not off [sic] the table.”

So you just want to talk about your new album?

“Tell me good questions about the music and we’ll continue.”

So you only want to talk about the new album (now it’s my turn to repeat myself)? You don’t want to talk about the [online] allegations against you?

“There’s no allegations against me, and I’m not going to talk about it. Rumours…”

There’s a noise like someone has put their hand over the mouthpiece of the phone. I think I can hear a muffled voice. Then silence.

I listen for a few seconds. But Marilyn Manson has gone.

It doesn’t take long for the shit to hit the fan. There are calls from Manson’s team asking what Hammer was thinking bringing up Evan Rachel Wood, and why a “heavy metal magazine” – their exact words – is even engaging with a topic like this. They also insist that Manson didn’t hang up, that the line cut off. At one point, they ask if the magazine can pull the piece and not run it. There’s an implication that if it runs, it could damage future relationships between the magazine and Manson. Offers from the magazine for Manson to clarify his comments and position on the issues raised are turned down, including a further set of questions surrounding Evan Rachel Wood, Esmé Bianco and the #MeToo movement.

To be clear: there’s no suggestion that the person Evan Rachel Wood has accused of abusing her is Marilyn Manson. Wood herself has refused to reveal the name of her abuser (after a Twitter user asked why she has never named them, she replied: “They threatened to kill me or have me killed”).

Nor is Manson’s silence any implication of guilt. Seen one way, his reluctance to engage with questions about his relationship with Evan Rachel Wood and the culture of abuse generally is logical. Even simply acknowledging what has been said could be viewed as giving credence to online allegations.

But it is frustrating that an artist who was never afraid to take on the bastions of power and their abuses is suddenly ducking the issue of personal abuse and the culture that for so long has either ignored it or glorified it.

When he talked of fantasising about smashing Evan Rachel Wood’s skull with a sledgehammer, Manson wasn’t just exercising his artistic or personal right to free speech, he was doing what he has always done: saying something outrageous, crossing boundaries, testing the limits of people’s tolerance for transgression. All the things we wanted from Marilyn Manson.

But culture has shifted. The #MeToo and #TimesUp movements have cast his words in a different, truer light. Women – including ones who have been close to Manson at points in his life – are threatened and abused on a daily basis. Talking about smashing in a partner’s skull isn’t provocative – it’s pathetic and psychopathic; calling someone 158 times and cutting yourself until they take you back isn’t romantic, it’s abusive. As Evan Rachel Wood’s testimony about her treatment at the hands of an unnamed partner show, these situations are real.

This isn’t an attempt to ‘cancel’ Marilyn Manson, just an attempt to engage him in a broader conversation about an era where some of the old rock’n’roll ways look increasingly toxic, and his place in it. “We’re living in a world where everyone’s afraid of everything,” he said at one point during our conversation. In his case, that fear apparently extends to discussing a subject that’s both timely and real.

During one of his many circular digressions in our interview, Manson once again brought the subject of conversation back around to We Are Chaos. Where in the past, he said, he had used his songs and his persona to hold a mirror to society, here he was turning it inwards. “I use a mirror on myself,” he said.

What he sees when he gazes into that mirror isn’t clear. Because right now, the phone line is silent. And so is Marilyn Manson.