Many thousands of words have been written about Michael Schenker since 1970 when, as a raw 15 year old, he joined elder brother Rudolf’s band the Scorpions. The adjectives ‘mercurial’, ‘eccentric’, ‘selfish’, ‘egotistical’, ‘hot- headed’ and ‘self-destructive’ – even ‘genius’ – are all regularly applied to the Sarstedt-born guitar hero but few have dug beneath the surface of this painfully shy yet enigmatic individual. Which is, of course, what Classic Rock intends to do.

Our audience with Schenker takes place in the dressing room of London’s Mean Fiddler venue, where getting him to talk about himself or his work is like asking him to knit fog. Schenker claims to ignore reviews and the results of interviews he gives, but while professing not to give a damn about what people think of him, he begrudgingly reveals the opposite is true. Enquire about rock media’s obsession with ‘Mad Mickey Schenker’, the cartoonish maverick who cuts off his hair, destroys his trademark Flying V guitars and disappears when the going gets tough and Michael is, for once, candid.

“When Ozzy Osbourne, Whitesnake or whoever approached me to join them, I always ensured there were too many conditions,” he confides. (He also declined to audition for The Rolling Stones.) “I was so insecure, I made it impossible for them to take me.

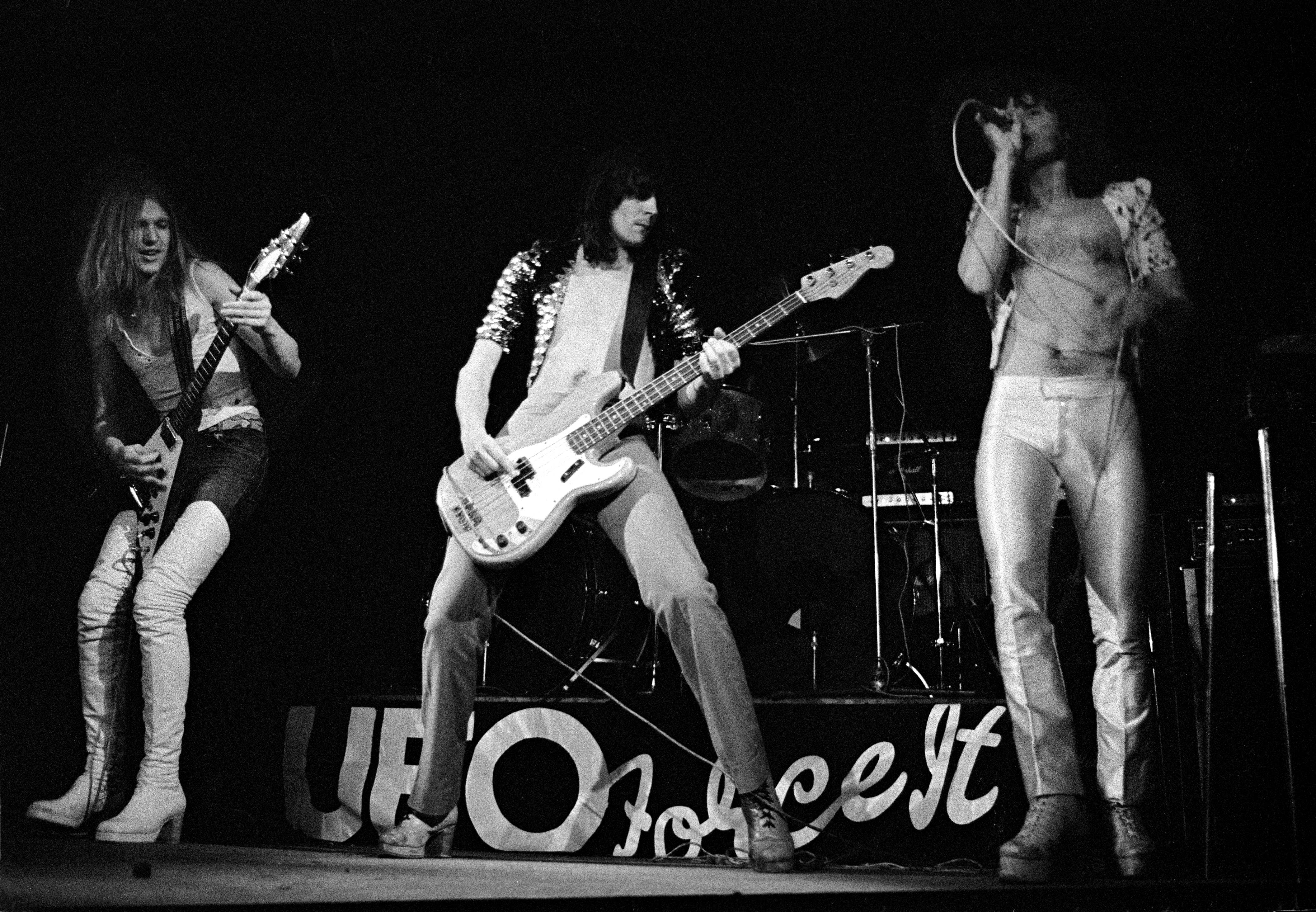

“Life, as well as music, is full of ups and downs,” Michael adds, in response to the suggestion that troughs have outnumbered peaks since he left first the Scorpions, then UFO (as the latter were about to go global with 1979’s Strangers In The Night), then abandoned the Scorpions again after Lovedrive.

“I’ve never cared about being commercial and could have joined some of the world’s biggest bands, but I’m happier without people telling me what I’ve done isn’t good enough for the radio,” he says simply. “My peace and freedom are important.”

Michael is now based in Germany again after a frustrating time in America that prevented him from getting to know his two sons. Tonight’s show is opened by a band called Faster Inferno that feature his 22-year-old, Tyson, and a third Schenker – 18- year-old Taro – joins MSG for an encore of UFO’s Doctor Doctor. Given his chequered experiences, does Schenker Snr have any practical advice for the Flying V-wielding offspring that seem set to follow in their father’s footsteps?

“They’re smart enough to figure things out for themselves,” he decides. “I had very little to do with their upbringing, and the man who was their father figure did a much better job than I could’ve done. They know very well that I’ve been ripped off many times in my career. The best that they can do is do better than I did.”

In typically erratic style, Michael has just released Tales Of Rock’n’Roll, a quarter-of-a-century commemoration of a solo career that, were we to nitpick, actually began 26 years ago. But, as becomes obvious while retracing the Michael Schenker Group’s trajectory, little in the blond axeman’s world ever goes to plan.

He explains walking out on the Scorpions during the Lovedrive tour by saying, “I kept forgetting that I didn’t like being in [other people’s] bands” – but the very next thing Michael did was to follow manager Peter Mensch’s advice and audition to replace Joe Perry in Aerosmith. According to Steven Tyler, in the official Aerosmith book Walk This Way, Michael breezed into the rehearsal room with the words “Hello, I’m taking over. Before I join your band, I want it clear I’m taking over right now. Here – my jacket – take and hang up”.

Michael’s eyes narrow like it’s the first time he’s heard this quote. “No, no, no… it wasn’t like that at all,” he protests. “Steven Tyler is a big fan of mine but it was a weird situation and everybody was pretty drunk and, of course, Steven ended up in hospital. We all write our own book the way we remember it.”

While in Boston, Michael bumped into Geddy Lee and Neil Peart from Rush, with whom he’d toured in UFO, and there was talk of forming a group. “It wasn’t really where I wanted to be,” he says now. “Have I ever thought of where such a line-up might’ve taken me? No. I don’t deal in ‘ifs’ or ‘buts’.”

Working in London with the first Michael Schenker Group line-up of ex-Montrose drummer Denny Carmassi and future Mr Big bassist Billy Sheehan, Michael buckled under problems with alcohol and drugs, going AWOL again. “He was caught between heaven and hell,” says brother Rudolf. “He was playing the best I’d ever heard him, but mentally he was in terrible shape.”

“I hospitalised myself,” Michael explains. “I’d been taking tablets for stage fright – the same ones that killed Keith Moon – and they were highly addictive. It was a tough withdrawal.”

Arriving from Jeff Beck’s band, drummer Simon Phillips and bassist Mo Foster plus current Deep Purple keyboardist Don Airey all played on MSG’s self-titled debut, which was produced by Rainbow’s Roger Glover. “Peter Mensch offered ‘Mutt Lange’ for my first album but I refused,” Michael casually reveals. “He produced all of Mensch’s bands and I didn’t want to be the same.”

Fortuitously for all concerned, a demo by unknown singer Gary Barden happened to be playing just as Michael walked past the Head of A&R’s office at Chrysalis Records. The chemistry between guitarist and the swiftly hired singer was instantaneous enough to bestride a couple of giant hurdles:

“Herr Schenker was very clean at the time, but he didn’t speak much English,” recalls Barden today. “I had my own problems with communication [he has a stutter] but the music spoke for us.”

Tough yet anthemic rock songs like Armed & Ready, Victim Of Illusion and the epic Lost Horizons made the album a Top 20 success in the UK. Little did anyone know myriad personnel changes and self-inflicted damage would ensure MSG had already reached their commercial peak in Britain.

A second album, confusingly also titled MSG, arrived in 1981, by which time the band comprised Barden on vocals, ex-UFO guitarist/keyboard player Paul Raymond, former Sensational Alex Harvey Band bassist Chris Glen and the much-travelled Cozy Powell on drums. On paper it was a splendid line-up but Schenker told Sounds magazine:

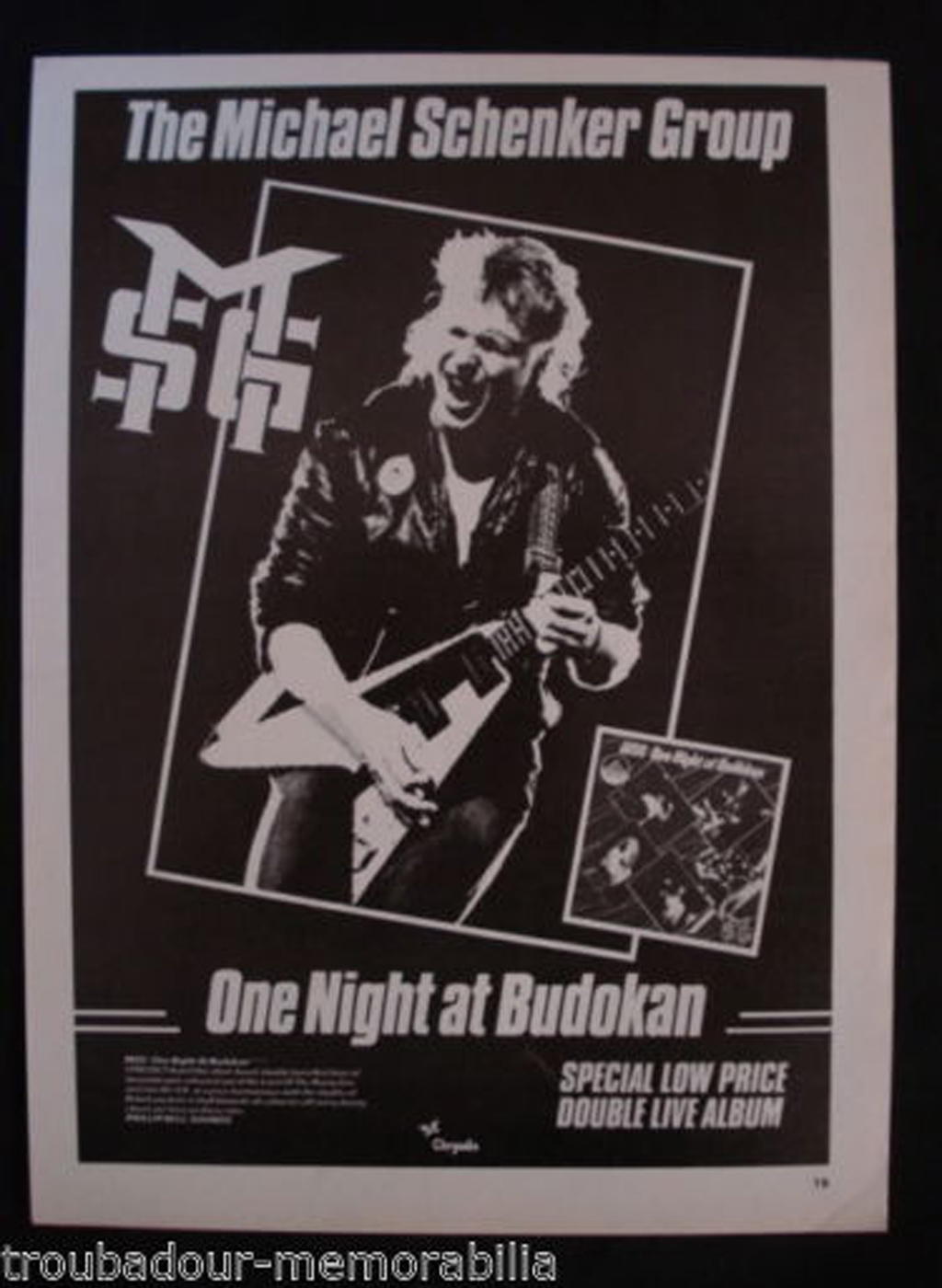

“I wouldn’t use [Ron Nevison] again if he were the last producer on earth.” Despite this outburst, Michael has worked with Nevison many times since, although the 1981 MSG double concert set One Night At Budokan was self-produced by the group.

It proved to be the last will and testament of what many consider the classic Michael Schenker Group. For Assault Attack in 1982 another SAHB man, Ted McKenna, had replaced Powell, Graham Bonnet had taken over from Gary Barden and the band had new representation. The switches were ironic, as Powell had sided with Peter Mensch to engineer Barden’s sacking.

“I still don’t know how that happened,” puzzles Michael, scratching his head. “It was other people trying to ‘improve’ MSG. Cozy and Peter both wanted a better singer. Peter wanted David Coverdale, I wanted Graham Bonnet.”

But hold on a minute… wasn’t the band called the Michael Schenker Group, not the Peter Mensch Group?

“Don’t you think I know that?” says Michael, patiently. “But if they have something better to offer then why not listen? Sometimes you win, sometimes you lose.”

“Michael was riding the wave; people were ganging up on him,” is Barden’s generous perspective of his dismissal. “He’s not English or American, and people took advantage of his German temperament. If they forced him into a corner, he’d say ‘Fuck you’ and get pissed. But we were all out of our heads, and I’m not bitter.”

After MSG cited the famous ‘musical differences’ cliché in regard to Barden’s departure, ex-Rainbow singer Bonnet arrived. “I went to see them play in Los Angeles and afterwards said to Cozy, ‘Great show’,” recollects Graham. “He asked, ‘Do you wanna join?’. They went back to England and I got a call a few weeks later.”

Bonnet had never written lyrics before – a fact that Michael learned only recently. But as Michael attests, the Martin Birch-produced Assault Attack is “the most popular MSG album with musicians,” also housing the staples Rock You To The Ground, Desert Song and Assault Attack. However from the public’s perspective, Bonnet’s tenure in the band would last for all of 15 minutes.

At a Sheffield Polytechnic warm-up for 1982’s Reading Festival, the singer imploded. An inebriated Bonnet took great delight in hauling roadie Steve Casey from behind the speakers, waving his penis at the crowd and exiting both stage and group. “I made a complete fool of myself, had too much fun in the afternoon then an argument with Michael and don’t remember much of the experience,” admits Bonnet, who’d been drinking on top of prescribed medicine. “There’s a tape of the show… I hate to think what it sounds like. It’s something that I’ve never lived down.”

“Was the Sheffield gig an embarrassing experience?” muses Michael. “No, we finished the set instrumentally and it still went down well. It’s true we used a rhythm guitarist, but that was because Andy Nye [keyboardist] didn’t play guitar. A reporter made up the fact I couldn’t play those parts. What’s he doing for a living now?”

With MSG still committed to a crucial gig, a representative arrived at Barden’s house in Hampstead. Despite having formed his own band, Statetrooper, he agreed to do Reading with them after just six hours of rehearsal. “I’m just too nice,” the singer deadpans. “Michael’s manager was actually crying, saying he was gonna lose everything.”

Nobody expected to see Barden again and the festival was such a huge success that the singer was welcomed back on a permanent basis. All the same, Michael doesn’t rate the resulting 1983 studio set Built To Destroy too highly. Neither did then-Sounds critic Garry Bushell, who wrote a merciless one-star review – which panned Barden’s “sub-Bad News vocals”, namechecked Rudolf Hess and ended “[This] doesn’t even reach the average heights that MSG have scaled before” – that Barden claims resulted in a visit to the magazine’s office.

“Bushell said, ‘Touch me and there are 20 security guards, you’re outta the building’. It was fucking pathetic,” he recalls. Bushell denies this reprisal ever took place: “I’d definitely have recalled being threatened by a muppet,” he states. “But if Barden wants to know, tell him I’ll see him in the beer garden of his choice to settle the argument.”

Unsurprisingly, the 1984 live disc Rock Will Never Die proved to be the last Michael Schenker Group release for a decade. “We were doing cocaine until we dropped,” reminisces the now-clean Barden.

“Everything fell apart during a US tour,” agrees Michael, who doesn’t recall whether Barden or Chris Glen was the first to hand in their notice. “Gary was drinking quite a bit and I wasn’t too happy about that. And so MSG ended for a while.”

Schenker firmly denies printed allegations that he went into rehab during the three years he then spent away from music. “My new desire was to experience a partnership,” he insists. “I wanted someone to make decisions with.”

That lucky partner was Robin McAuley, a singer formerly of Grand Prix and Far Corporation (who’d scored a hit with a cover of Stairway To Heaven in 1985). Under the revised handle of the McAuley Schenker Group, Michael and Robin toured with Rush, Def Leppard, Ozzy Osbourne and Whitesnake, releasing three albums – Perfect Timing (1987), Save Yourself (1989) and, again, MSG (1992) – which largely toned down showmanship in favour of commercial songs.

“The more melodic aspect was something that came from me,” claims McAuley, who now has a band called Bleed. “Some people liked it, some didn’t. But with me, Michael’s songs went to radio and MTV for the first time. Several times we almost crossed over but then he’d hit a wall and you’d go, ‘Oh shit’. He has a big heart but it’s often 10 steps forward and a thousand steps back. There are times when you think you know Michael but nobody ever does.”

“I clashed with [producer of Perfect Timing] Andy Johns because he was drinking, but Save Yourself was a good album,” reflects Michael. “But in 1989 I ended up in rehab because I was addicted to various tablets I was taking to calm my nerves. Just like being in UFO, McAuley Schenker Group hadn’t made me any money and after a while I didn’t want to be part of a partnership anymore.”

In late 1990, during one of the McAuley Schenker Group’s many breaks, Michael agreed to do a favour for his friend Warren DeMartini and temporarily replaced Robbin Crosby in LA hair-rockers Ratt.

“That was a pain in the butt – I was caught between two groups of enemies,” he winces.

The Ratt experience was followed by a similarly ill-fated venture called Contraband, with members of Shark Island, Vixen, LA Guns and Ratt. Their one and only album savaged by the critics in 1991, Contraband saw their tour collapse after just two gigs.

Preparing for what he felt would be his next step, Michael embarked upon half a-dozen self-improvement programmes. He tried to stage a charity famine concert, even going on hunger strike until musician friends joined the cause, but was eventually forced to throw in the towel through a lack of interest. Seeking to reward his fans for their patience, the self- financed acoustic Thank You album was then issued via his own Michael Schenker Records in 1993.

“I knew that if I sold three CDs a day I’d have enough to eat,” he recalls. To promote Thank You, Michael boarded Greyhound buses and turned up at radio stations, often unsolicited, to request interviews. “By the time I came home, enough fans had bought the album to make me rich,” he smiles, barely hiding his pride.

Declining a lucrative approach from Deep Purple to replace Ritchie Blackmore, Michael made the first of several returns to UFO for the Walk On Water album and tour in 1995. Unlike others that would follow, this initial reunion was satisfying.

“I was excited by earning money for the first time and I wanted to teach them how [to do it],” says Michael. “One of my conditions for going back was that because the name [UFO] had been so abused since 1979, half of it became mine.”

He formed a new Michael Schenker Group in 1996 but, like a spouse in a bad marriage, spent years flitting back and forth from UFO. Produced again by the once maligned Nevison, MSG’s underrated 2001 comeback disc Written In The Sand featured an above-average vocalist in Leif Sundin. The same hasn’t necessarily been true of other singers; Michael has declared that Keith Slack was “average” while Chris Logan (who sang on Be Aware Of Scorpions in 2002 and Arachnophobiac a year later) was by far the worst of a mediocre bunch. Michael blames the comings and goings on his inability to afford retainers for backing groups; fans have learned to live with the changes.There were two further UFO albums, Schenker returning to the band for the last of these (2002’s Sharks) after an infamous drunken performance in Manchester during which he thanked the audience for booing him. Michael allowed the band to replace him with Vinnie Moore and swears he hasn’t heard You Are Here, the 2004 album they made without him.

“And you know what?” he says, sitting up straight to reinforce the point, “I’m not even curious about it. These days I try to think of music as chocolate: you savour it better if you experience it less.”

After splitting up with his wife in 2002 Michael hit the doldrums and spent almost 12 months in court.

“I lost my recording studio, cars and everything,” he rues. “All I had left was a bicycle and a few shirts. Then one day I got up and snapped out of it. I did a crash course in computers – having a website has really allowed me to connect with my audience.”

He doesn’t lie; visitors to www.michaelschenkerhimself.com can read postings about brushes with the law, drug addiction, the pawning of equipment and even child support disputes that others would find intrusive.

“Some people say it’s too personal but I owe my fans the truth,” he shrugs, adding apropos of nothing: “I was supposed to tour America but couldn’t go because two women were waiting there to have me arrested.”

Although a cancelled British trek with Yngwie Malmsteen last May further undermined confidence in him as a box-office attraction, Michael has no regrets. “I agreed to being a co-headliner and that changed,” he rationalises. “That’s like being offered $1000 to clean a room and then only be paid $500. An agreement is an agreement and my true fans deserve to know what really goes on in my life.”

Let’s face it; Michael Schenker’s career is a clusterfuck. Singers have been deported mid tour, punch-ups erupted between band members and road crew and Night Ranger’s Jeff Watson even had to complete some of Michael’s guitar parts on Arachnophobiac after he suffered a nervous breakdown.

“That was at the tail end of my depression,” he sighs. “It was a tough time for me.”

Few musicians would admit that their latest album was eked out of a scrapped former project, but Michael happily volunteers the fact that Tales Of Rock’n’Roll was intended as a UFO album – the one that eventually became Sharks – hence bassist Pete Way playing on it.

“Phil [Mogg, UFO vocalist] didn’t arrive for the recording,” he explains. So, realising that an anniversary was imminent, Michael found a young Finn called Jari Tiura to track most of the vocals and contacted all six of MSG’s previous frontmen – Barden, Bonnet, McAuley, Kelly Keeling, Sundin and Logan – to participate. Perhaps surprisingly, given the circumstances of their various sacking and departures, all agreed.

“Things didn’t end badly with anyone,” Michael semi-scowls. “Where you are getting these stories from?”

Where shall we start? You sacked Gary Barden and reinstated him, then Graham Bonnet walked out after the Sheffield fiasco… “I don’t read any of the gossip about myself, although there’s a lot of it out there,” he responds; “it’s how I keep a smile on my face.”

Astonishingly, Michael remains on good terms with many of those he’s worked with. The ex-MSG members we spoke to still speak of him like they would some flawed, eccentric-yet-loveable relative.

“I don’t think anyone was paid to appear on Michael’s new album but he repaid my favour with a guest appearance on my solo album [The Agony And Xtasy],” reveals Barden.

“He seems a lot happier these days and, for all his problems, I wish there was somebody like Michael Schenker on every street corner in every country.”

Despite the ignominy of his own exit, Graham Bonnet still regrets his one night of madness and would rejoin the Michael Schenker Group in a heartbeat if requested to do so.

“He’s back in Germany again and seems to have sorted out some of his demons,” Bonnet observes, “but I don’t really don’t see it happening.”

If Michael’s career seems rudderless, hope is on the horizon. He plans to make a record with brother Rudolf, who has approached Peter Mensch to oversee the project, as The Schenker Brothers.

Confides Michael: “Carlos Santana is going to be a part of it, too. It’s looking like I will also be writing for the next Scorpions album.”

In closing, Michael Schenker attempts to sum up his 51 years on the planet. His existence is haphazard but he’s long since learned to accommodate perpetual change.

“My audience is largely made up of musicians and that’s something I’m absolutely fine with,” he concludes. “The good thing about having gone through so many ups and downs is that it brings a wide range of experiences. It’s made me a better person.”

This was published in Classic Rock issue 96.