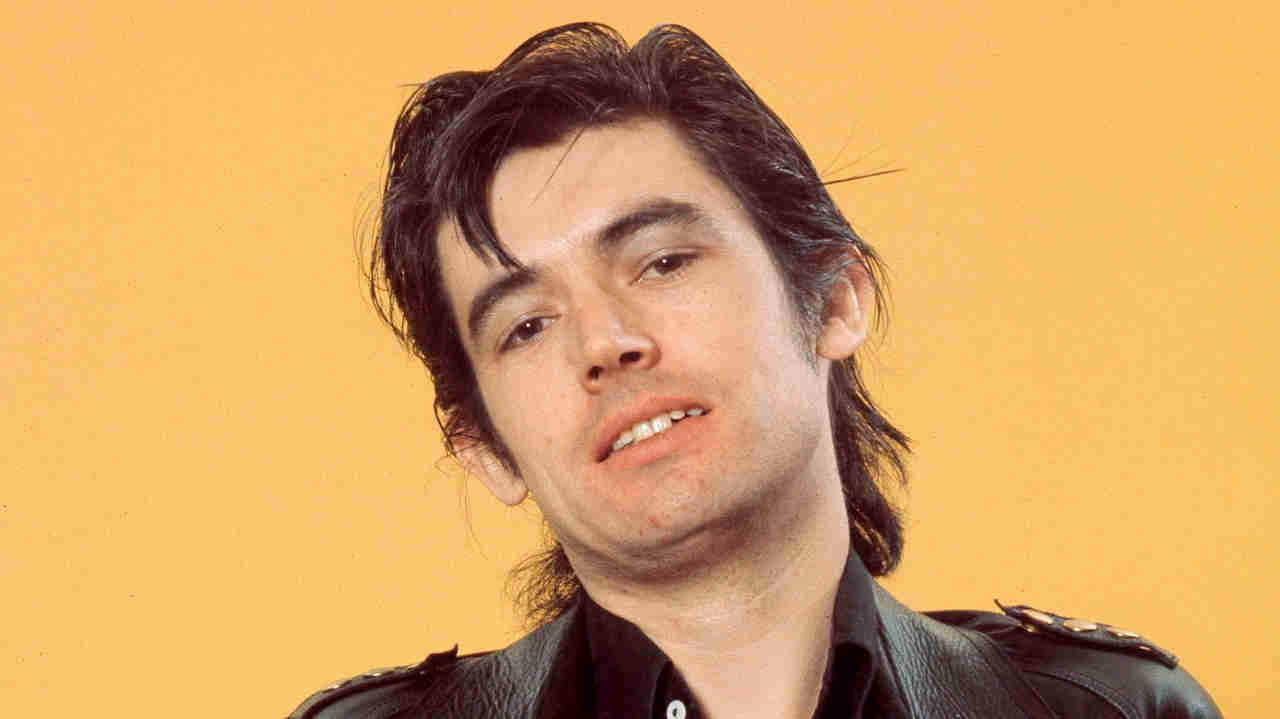

“I become a Colossus of Maroussi, I can do anything!”: Michael Stipe on the period when R.E.M. became a stadium band and he embraced his inner showman

It’s 30 years since the Athens, Georgia legends began a huge tour to support Monster and frontman Stipe had no choice but to up the flamboyance in his frontman game

By 1995, R.E.M. hadn’t toured in six years but you could hardly say the decision to take themselves off the road had caused a downturn in fortunes for the Athens, Georgia quartet. Quite the opposite: during that period, they hunkered down in the studio and released a pair of early 90s classics in 1991’s Out Of Time and quickfire follow-up Automatic For The People, which came out the following year. Both sold in the multi-multi-millions and made R.E.M., already a sizeable, arena-playing band, absolutely huge. Monstrous, in fact.

They were ready to get back out there and their 1994 record Monster was written with big stages and bigger crowds in mind: after the low-key, acoustic-heavy sounds that made up much of Automatic For The People, this was loud, crunching rock music built for mass projection. The tour, which hit the road 30 years ago this week when the band kicked off a near year-long trek with shows in Australia, would also require an about-turn from frontman Michael Stipe, who cut an introspective albeit captivating figure for some of the songs across those two records (OK, maybe he wasn’t so introspective on Shiny Happy People). He was certainly in the mood to embrace his inner flamboyant showman, and a few years ago he told this writer about what it entailed to get into the zone for the band’s biggest shows yet.

“I was so focussed on that tour,” he said. “Performing and being frontman required an immense amount of psychic energy, moreso than being a drummer. I say that with all the love in my hear for every drummer who’s ever sat behind a drumkit but being the frontman requires a different level of psychic energy to carry the crowd, to life them, to pull them up and out when they were not completely present, to really create the mood and the atmosphere that’s required for a successful live performance.”

Going onstage each night on a tour that took in arenas and then stadiums across the globe was an experience that Stipe described as “nerve-wracking” but he said at every show, by the third song he’d be firing on all cylinders.

“It’s always the third song. That’s when the adrenaline takes over and I become a Colossus of Maroussi,” he explained, referring to the titular character in Henry Miller’s 1939 novel. “I can do anything. Henry Miller is gonna write a book about me! It’s an absurd journey through adrenaline. Something that all of us will experience at least once in our lives, I experienced as part of my job for the best part of 32 years.”

After a batch of cancelled shows so that drummer Bill Berry could recuperate after suffering a brain aneurysm onstage, the tour resumed in April 1995 and the band arrived in the UK for a run of massive outdoor shows in good nick. Stipe had personally overseen the support slots, which included Blur, The Cranberries (“god bless Dolores and her spirit,” Stipe said) and Sleeper. “We had great opening acts,” he marvels. “I can say that I was always a fan of Blur and so being able to see them perform was a great joy.”

Radiohead also opened up for the Losing My Religion stars, a meeting that led to the new groups becoming well-acquainted and frontmen Stipe and Thom Yorke forging a lifelong friendship. “I went and presented myself to Thom,” Stipe recalled of the first time they spoke. “And then he presented me to the rest of the group. I think we were sunbathing together outside of the dressing rooms. It was a beautiful summer day.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Selecting such a stellar support line-up, Stipe explained, was a good way of gee’ing himself ahead of his own performance. “I just watched from the side of the stage three astonishing acts do what they do and raise the bar,” he stated. “Not being naturally competitive is a good thing in these kind of situations because if you’re R.E.M., you have the ability to handpick the opening acts and so you choose bands you want to watch on the stage, but then they’re raising the bar with every performance so I’m sure that’s what was going through my head.”

“Those giant outdoor things,” he continued, “they’re really fun but it takes a different kind of psychic energy to pull the audience towards you through the entire course of a set. You have to really reach the back rows, you have to be at the back of the field, near the toilets, near the T-shirt stands, engaging those people as much as those right up front.”

By that point, Stipe said, he had become the frontman who could do that. “I had become this creature who could do that thing and do it really well. It was terrifying because since 1989, the size of the show had grown immensely.”

In terms of adapting to the now-gigantic setting, the band took inspiration from their old pals U2, Stipe said. “It was presenting it in a way that was pulling from the work they did with Achtung Baby and Zooropa,” he said, “and pulling from glam-rock and the historically British idea of music as theatre and presenting something in a very different way than R.E.M. had before. It was a new experience for us and something I was having a great deal of fun with.”

It was a role that Stipe would successfully inhabit for the rest of R.E.M.’s career. As you can see from their Glastonbury performance below, he was born to be a frontman doing his thing in front of the masses.

Niall Doherty is a writer and editor whose work can be found in Classic Rock, The Guardian, Music Week, FourFourTwo, Champions Journal, on Apple Music and more. Formerly the Deputy Editor of Q magazine, he co-runs the music Substack letter The New Cue with fellow former Q colleague Ted Kessler. He is also Reviews Editor at Record Collector. Over the years, he's interviewed some of the world's biggest stars, including Elton John, Coldplay, Radiohead, Liam and Noel Gallagher, Florence + The Machine, Arctic Monkeys, Muse, Pearl Jam, Depeche Mode, Robert Plant and more.