Mick Box is all smiles. Standing on the doorstep of his outwardly anonymous North London residence, the Uriah Heep guitarist wrestles Iggy, his dog, back inside and offers a cup of tea. As the kettle boils, one’s appraising eye is drawn to surroundings unlikely to fool any Through The Keyhole panelist, no matter how lacking in rock literacy.

Furniture to grace any baronial hall is brightened by white décor; guitars and paraphernalia pertaining to guitars seem to proliferate at every turn, Roger Dean’s iconic Demons And Wizards cover art hangs in the front room; Biscuit, the unflappable ginger cat, purrs contentedly beneath a wall of extensive and tightly packed gold and silver discs awarded down the years to mark the kind of physical record sales that today’s rock stars can only dream of.

To say that Mick Box is a personable chap is to ludicrously understate matters. Seemingly unaffected by the trappings of fame, he’s open, chatty, brimming with hilarious anecdotes, and exactly the sort of person anyone would relish a night down the pub with.

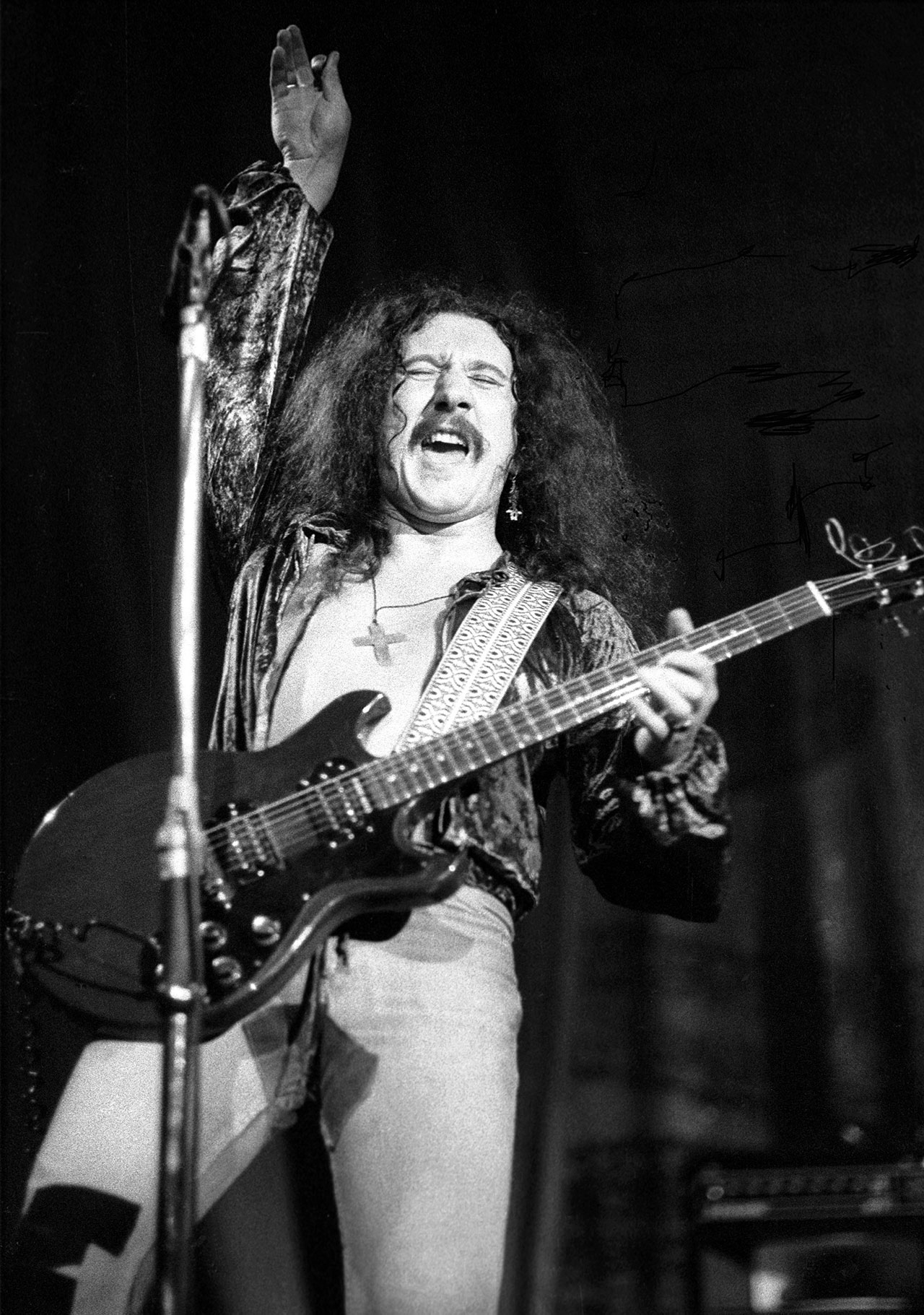

Of course, he has also been the driving force behind Uriah Heep, one of 70s rock’s biggest bands, for almost half a century. And despite his sunny demeanour, Mick’s life hasn’t all been easy livin’ and ’appy days, as he explains, from behind blue-tinted shades, over a bracing cuppa char.

So here we are in Palmers Green, five miles away from where it all began in Walthamstow, something tells me you’d rather be here than Sunset Strip.

I’ve lived in America and Australia, but the draw-card’s always England. It’s where my heart is. Humour’s a big part of my life, and in America it’s a different type. Any catastrophe that happens here, you go down the local pub and joke about it. You don’t get that in other parts of the world.

Was there music in the house growing up?

No, I’m the only musical person in the entire family. But my mother was very supportive. She’d be the one standing over the record player, dropping the needle so I could learn a bit of guitar. The rest of my family were always saying to her: “When is he going to get a proper job?” And by then we [Uriah Heep] were very successful – big American tours, hit albums, Wembleys. But when we played the Albert Hall those family comments stopped, because to them that was the pinnacle.

Were you old enough to understand the full import of your father’s passing?

It was sad, really, because it happened on Christmas Day. He was a carpenter. On this particular occasion he came into my bedroom dressed as Father Christmas. He had a blackboard, easel and chalk. To me that was amazing – I could write something, rub it out and write again. It was magic to me. So he left me playing with that. Then I heard a noise outside my door and he’s been taken to hospital. The following day he passed away, a heart attack. That was my last memory of him. I was six. Even now, Christmas is bittersweet.

You must have had quite a matriarchal upbringing, with your mother and grandmother, and you as the centre of attention. Might that have encouraged the performer in you to blossom?

Probably. My mother helped me and never once put anything in my way. I was very lucky in that regard. Maybe with a father there he wouldn’t have been so supportive and it might have caused rucks. [Former Heep man] David Byron’s father didn’t support what he did. It became a real issue. He had to move out of home and even change his name.

Where was school, and how was it for you?

William Fitt Secondary School in Greenleaf Park. It was okay. I got eight passes in everything I needed to pass, but the only thing I wanted to pass was the school gates [laughs]. By then music was going to be my life. I had no other goal. I had to trade in my Telecaster to get my first major electric guitar, a Gibson Les Paul Black Beauty I bought from Eddie Moore’s music shop in Bournemouth, the only shop in the country that distributed from Kalamazoo in America. There was still money to pay, so I had to get hire-purchase. I promised my mum I’d get a job and when I’d made the last payment chuck it in and become a professional musician. And that’s exactly what I did.

It took me almost a year. I even cycled from where I lived, above a butcher’s shop on Forest Road in Walthamstow, to Liverpool Street and back each day to save the train fare. I worked for Vavasseur Levetus Export Ltd. I had my own office and it allowed me to dream. I was exporting to places all over the world, thinking: “I’d love to play a concert there.” We were doing shows as well, so I was sometimes getting in at three in the morning and getting up at six to cycle ten miles to work. I was that focused, nothing was going to stop me. I was going to be a musician for the rest of my life and that was it. Little did I know I was going to be in the same band this long.

Did you still dream of White Hart Lane glory as you entered your teens?

I was pretty good at football. I played for London Schoolboys, which was great because you got off school in those days. Then I started to see all the other kids growing, getting to six foot while I’m still five feet nothing. I was low gravity, stocky and I’d get stuck in. We were encouraged to do things they ban today, but the physical stuff was gradually being phased out and that was what I used to love about it. It was a quick decision in the end. I thought if I break a leg I’m out of the game; if I break a leg I can still play the guitar. No contest.

Did you and the guitar get on immediately?

Immediately. My mother bought my first guitar from a pawn shop in Walthamstow High Street. It was a Telston semi-electric single-cut-away sunburst with a single DeArmand pickup. It cost twelve pounds ten shillings. I never had to sit and do scales. Luckily I had good ears, so I just picked up what I wanted to play and played it.

Were The Stalkers your first proper band?

Yeah. And it was good. Basically the rock’n’roll medley for an hour and a half [laughs]. We did all the old Chuck Berry stuff, and there’s time for solos in those so it gave us a chance to branch out.

At the end of 1966, The Stalkers metamorphosed into Spice, and by now David Byron had been promoted from part-time guest singer to full-time vocalist.

When we were in The Stalkers we’d play rugby clubs, twenty-first birthday parties, universities, pubs, the lot, and our drummer was a guy called Roger Penlington, David’s cousin. So David used to come along to gigs, and after a few pints get up and sing the rock’n’roll songs. At that time our bass player, Richard Herd, was singing but we realised we needed a frontman. We set up auditions and David was there the whole time. You intrinsically know when somebody walks in the door if they’re in with a chance, and there was never that moment with any of the people that came along. Then I looked over at David and got that moment. So I said: “Come up, let’s play some songs,” you know. And he was great. I said: ‘There you go, you’re our boy.’”

Spice then signed with Gerry Bron?

The Stalkers were semi-pro, but Spice was when we decided to go professional. We were being managed by Paul Newton Senior, our bass player’s father, who did a great job. He got Spice a residency at the Marquee, our name in the music press, but he felt we needed to go further. So when we did The Blues Loft, High Wycombe he invited Gerry Bron, who had his own agency, management, studio and publishing. Gerry came down and particularly liked David and me, initially, because we wrote. So he put us in the studio. The songs sounded great and things started moving very quickly.

Bringing Ken Hensley in coincided with the band’s sound beefing up to heavy metal.

Listening to those songs back, we felt some keyboard embellishments would accentuate the colour in our template, so we got in Colin Wood, who laid down some piano parts. And although they gave colour, they weren’t what I was looking for. I was a big Vanilla Fudge fan, and that inspired me to pursue a Hammond player. The Hammond organ can be aggressive, romantic, bluesy, jazzy, everything our music was, and we needed a guy who could handle that. Paul Newton had worked with Ken Hensley in The Gods, so he added Hammond parts, and we all thought: “This is what we want to sound like.” He also came with a high falsetto, which meant we still had five singers, a lot of harmony. So with the template changing, we thought we might as well change the name of the band.

From Rolling Stone’s savage review of Heep’s Very ’Eavy, Very ‘Umble album onward, the press never seemed to approve of the band’s existence. The albums got more sophisticated, sold millions, but it was never enough. What do you think was the problem?

I don’t know. They say we’re part of the big four with Zeppelin, Sabbath and Purple, but we were the last. The others were already established when we came along, and the musical template was already changing in London, getting a bit folky, so we weren’t so much seen as: “Oh, another one”, as: “Oh no, not another one” [laughs]. Gerry Bron had put his money where his mouth was, put page ads everywhere, and all that publicity alienated the press. Our drive was the people. The people vote with their money. They bought the albums and the tickets. I put a lot of the bad press on the inside cover of the live album: “Uriah Heep sounds like a skin disease” [laughs]. I just took it with good humour. We were mullahed by everybody, but it made us into a people’s band, and it’s the people that count in the end. Critics criticise, it’s what they do [laughs].

By Salisbury, Ken Hensley’s songwriting came to the fore. Until then David and you were the main songwriters. It’s a seismic shift, not just artistically but in terms of the band’s balance of power?

Yeah, it was. But my thoughts have always been put everything on the table and the best survives. Ken was writing good stuff, so we travelled that path. Up until then David and I were intrinsically linked everywhere we went, but there was a little bit of drifting apart as we got into Heep and I don’t know why. It just happened. So yeah, Ken had a writing streak and you couldn’t ignore it.

David was quite the singer, with an incredible range and stage presence to match. But even as ever more ambitious albums – Look At Yourself through to Wonderworld – were pushing your profile to a stratospheric level alongside Purple and Sabbath, he was starting to find solace in the brandy bottle. What was missing for him?

It’s hard to find out what’s missing in anyone’s life, but I’ve always had a kid and family. That’s kept me grounded. He had his wife, Gabby, but he didn’t have any children. I come home and I have to take my rock’n’roll hat off and put my dad’s hat on, but he never had that. He was twenty-four-seven the rock star. From cleaning his teeth until the minute he went to bed, he never stopped. When you’re on the road you’re with the lads, having a laugh, getting boozed-up every night, and you can’t do that at home. But David could. While the rest of us put the brakes on – because the missus didn’t want to see you doing a half a bottle of Jack, plugging your guitar into the back of the TV and having a go [laughs] – he didn’t.”

In the midst of this, Gary Thain – who’s intuitive bass playing had helped drive the band’s sound since Demons And Wizards – was having problems that were to end in tragedy.

Gary kept a lot hidden. People take drugs, do high-powered jobs and nobody knows what they’re fuelling themselves with. Gary was very much in that mould. I roomed with him for years. He’d have a little drink, and everyone was popping pills and having a little smoke, though I never did. Never smoked in my life, anything good or bad. But Gary was always more experimental.

At what point did you get married?

I can’t remember now. Late twenties? I’m actually four marriages down.

But a wife and family has always been an essential element in keeping you grounded?

Yes. There was a time when I’d come home at five every morning with a bottle in my hand, then I had to get up at five to give my son a bottle. It’s a slightly different dynamic, isn’t it? And you only ever do the five in the morning feed with a hangover once [laughs]. I had that grounding, David never let up, and Gary was very frail. He had only one answer for everything. If he had toothache he’d put a valium on it, he’d never think of going to the dentist. That’s the sort of person he was.

Were your previous marriages victims of the road and the road lifestyle?

You’d need a whole book to go into the whole thing, but certainly my first marriage, yeah. We were out on the road all the time, being driven really hard. It was three months on the road then three months in the studio. You barely got home at all. Because Gerry made the investment he made, he wanted to see some return on it, so they drove us. They drove us too hard. I firmly believe that had they looked at the big picture, eased off a bit so we could go home and get grounded between tours, we wouldn’t have had as many casualties.

How excessive did the excess get?

Stupidly excessive. We were flying around America on private jets, selling out ten-thousand-seaters a night everywhere. We took whole floors of hotels, with bodyguards outside each room. It was complete madness. People think the rock stars were the only ones who indulged in all of this, but the entire industry were doing it. I can remember going to an accountants meeting in America, and the first thing he did was bring out a big mirror and pour a pile of coke on it. The next minute you’re all talking a load of shit. When you leave the room you don’t know what you’ve signed, and you’ve been had again! [laughs] It was just crazy. The entire industry was nuts on it. It was only when people started dying that people started going, hang on, this isn’t right.’

The price still seems to be being paid. When you look at some of the stars who’ve died recently, though they probably thought those excesses were far behind them, those blizzards of cocaine in their past probably contributed to their premature passing.

I’m lucky I remained grounded. After the last two years where everybody’s passed away, I’m still here. Though you do get to the point where you think: ‘Is my name on that bullet?’ Then you wake up in the morning and think: “No… ‘Appy days! Life’s worth living. Plug in the guitar, there’s another song to be written. Let’s go!”

In 1975, you fell off stage in Kentucky and broke your arm. You not only finished the gig, you also finished the tour. I know the show must go on, but surely there are limits.

It was the first night of a long tour. In those days Rod Stewart had white carpets everywhere; we had black. So we had this black carpet, and I used to run out on my own at the start of the gig, with the band already in position. They’d point a pencil spot on my hand and I’d play the guitar figure from Devil’s Daughter, then the stage lights up, the band comes in and it’s a super-powerful start. Now on any other tour, the crew would put a bit of white tape on the carpet. But they didn’t, and I didn’t ask them to. So I ran straight off the stage into the orchestra pit – bang! – with the guitar clanging all over the shop. They pulled me out, put me back on stage, but I’d dislocated my left arm. The bone was sticking right out. We had a bottle of Remy Martin there so I started drinking it. And halfway through the show a nurse arrived from the local hospital. David was instructed to do a really long chat while the nurse cracked my arm back into place. That really hurt, so I had some more Doctor Remy. Anyway, we got to the end of the show and went to the front of the stage to do the bow. I was still in a lot of pain, but the other guys had forgotten, so one of them grabbed it to take the bow. So I fell in the orchestra pit for a second time and broke my right wrist in four places. Up again, taken to hospital. Gerry Bron, who’s a big guy, sat on me to hold me down while the doctor put my hand in this claw thing with five springs, broke it back into place and put a cast on.”

After High And Mighty, David’s behaviour became so inconsistent he had to go. What do you remember of that time and how did it affect you personally?

It was absolutely terrible. It got to a point where he lost all his priorities. It was more than how he dressed up, looked, sounded and performed, it was all going askew. He’d lost the plot, basically. There was a point in Philadelphia where we were playing in front of twenty thousand people. He walked on stage at the start of the show, put his foot on the base of the mic stand and it banged him in the mouth. They crowd are cheering and he thought they’re all laughing at him, so he told them to eff off. It was all downward from then. One thing after another, until you’d avoid his company because you knew it’d end in embarrassment. Then in Spain, at the end of a European tour, we couldn’t get in the venue, a modernist one with glass all around, he kicked a door and smashed it. That was it. David got fired. For me personally it was terrible, because of where we came from. I remember the guy when we were sticking up posters for our first gigs, trying to avoid the police, but it got to a point where the drinking just got hold of him.

Shortly after Conquest, I tried to get him back in the band. Me and [bassist] Trevor Bolder went over to his house in Henley and I said: “Look, I’ve got a record contract. What about us trying to get the band back to full strength, with you and me as writers?” But he’d gone by then, he was fuelled by so much alcohol he was floating. He had three managers all blowing smoke up his backside and wasn’t thinking clearly. He wouldn’t even consider the offer, which was a real shame.

You were approaching thirty at a time when rock’n’roll was still considered a young man’s game, did it ever cross your mind to call it quits, to call time on Heep?

No. I’m a fighter. I firmly believe if you’ve got good quality musicians and can write great songs, you’ll always win through. After Conquest, when I disbanded everything because it wasn’t going in the right direction, I might have thought about it, but two days later I was back on track and had a whole band together. It’s never occurred to me to quit, because I started it, why shouldn’t I finish it?

Heep started as a cult band, sold millions, conquered America, broke new ground… yet somehow you’re a cult band again. You’re respected, loved, your influence on everything from Queen to modern prog is undeniable, yet here you are in Palmers Green. Where are the Heep millions?

Good question, And I’d like to find out myself [laughs]. Along the way it disappeared into the ether. I couldn’t say I didn’t do okay, but certainly what should have been in the bank never made it. We got ripped off, things went missing, but there you go. I’m still doing what I love, making music, travelling the world. Money comes and goes, it just so happens that it went more than it came [laughs].

How do you fill the days when not on tour?

Walk the dog twice a day, run my sixteen-year old son, Romeo, to his sport and school, go out to the movies with my wife, Sheila. Just normal stuff.

Do the neighbours know who you are?

Prior to buying the house next door my neighbour was on holiday in Las Vegas. He was in reception at his hotel, looked down on the floor and there was a Mick Box guitar pick. He was a Heep fan, so he stuck it in his wallet and it’s been there ever since. Then he bought the house next door with no idea I lived here. So he came round to introduce himself and just looked at me in disbelief. Now he comes to all our London shows, goes down the front and some of the kids see he’s a different age and want to know what he’s doing there. And he’s like: “That’s my neighbour up there.”

You seem comfortable in any company, and it seems to work both ways.

I hope so. I wouldn’t want it to be any other way. I don’t have any airs and graces. At the Classic Rock Awards I saw Slash with his bodyguard, so I went to have a pee next to him just so I could say I had a slash next to Slash [laughs]. Though under the circumstances I didn’t shake his hand.

Do you still wish you could phone David Byron? Was there anything left unsaid between you that you wished you’d said?

Yeah, I’d love to pick up the phone. I could say: “Let’s write a song. We’ll stick it up on the net for free and get a buzz going.” I still think he’s one of the best singers there ever was in the rock field. He had that ability to live inside a song and his voice communicated with everyone, in a way that I’d never felt before or since. Sometimes [current Heep vocalist] Bernie [Shaw] hits it right on the nail and I get a chill then, too. There’s nothing I didn’t say to David, really… we said it all. We felt it all, we lived it all, it just went astray – from his point of view, not mine. If you start believing too much in that side of things, it’s got to go wrong. I can’t see it any other way.

You’ll be seventy in June. Is there still an outside chance that you might finally grow up and get that proper job?

I’ve got it [laughs]. I’ve still got the same passion for what I do and that’s my driving force. I love it. I’ve still got ambition. I’ve just taken on new management, changed agent. I could ride it out at this juncture, but decided to make changes to keep moving forward. I’m writing a new album with Phil Lanzon, our keyboard player. We put songs together and record them as demos for the new album.

Any regrets?

I try not to have any. But I regret the loss of band members, because I still believe that had we not driven it so hard and been more compassionate to the people that made it in the first place, it may still have continued. Saying that, there were no Priorys or places for people to go to to seek help, you had to do it on your own or end up in rock’n’roll heaven. That’s the only regret. Everything else, you’ve just got to learn from.

And, coming from humble beginnings in Walthamstow, this looks a lot like success.

This is success. Success is that I’m still playing, still doing what I love. Success is when somebody comes up to me at a show and says: “I saw you play a concert, it was the most fantastic night of my life, I picked up a guitar, I play music now, I’ve got a band of my own and I just want to thank you.” That’s success. And all the dinner plates [he gestures to the many gold discs]? Well, they’re nice enough up on the wall until someone comes to do some work at your house, takes one look at them and doubles their price.

Reissues of Look At Yourself, Demons And Wizards and The Magician’s Birthday are out now on vinyl, CD and digital on BMG Records.