If we can pinpoint a moment when the British establishment officially began to take the counter-culture seriously, there’s a fair argument for dating it at 31 July 1967.

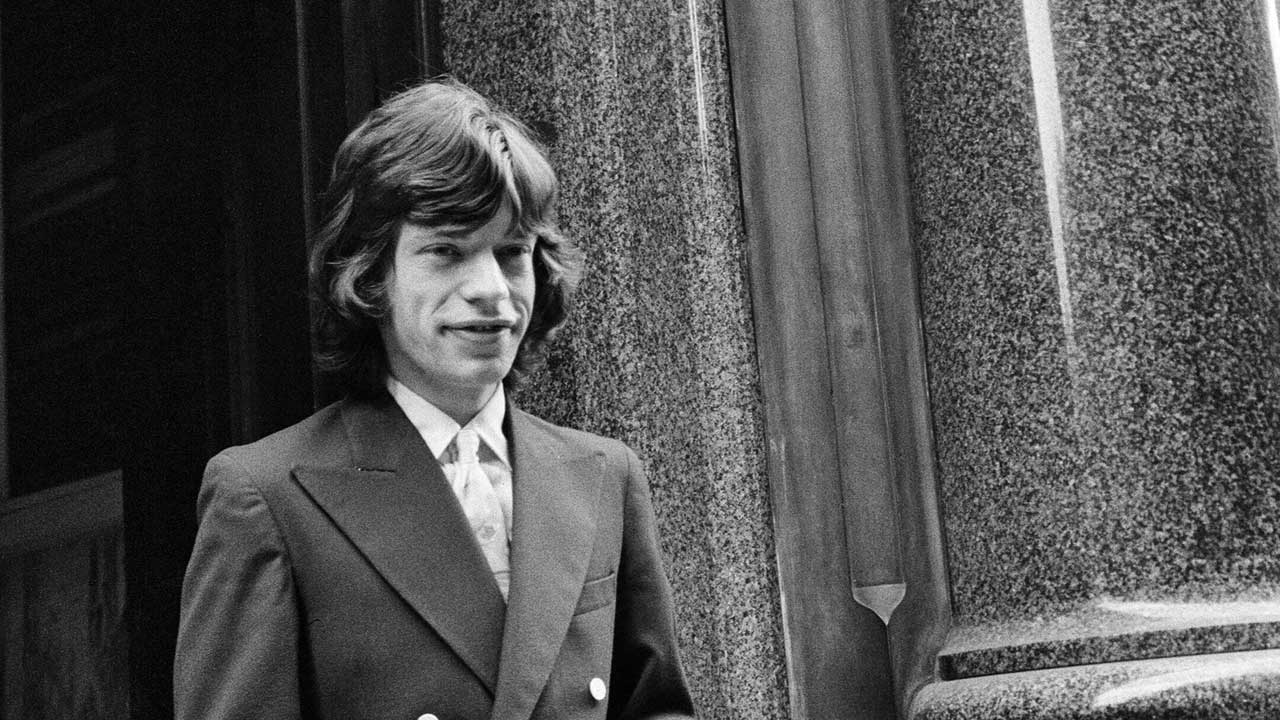

That was the day that a faintly bemused Mick Jagger, the voice, face, and indeed lips of The Rolling Stones, found himself brought before a panel of the great and the good, challenged to defend and explain the permissive society amid fears that a generation of young people were being led by this pied piper of pop and his disreputable friends into the drug-addled bowels of hell.

Some context is of course essential: Jagger had been released from prison that day, having seen what was initially a three-month sentence for possession of amphetamines suddenly quashed. He’d only spent one night in Brixton prison in the end, the result of the infamous drug bust at Keith Richards’ home at Redlands in Sussex.

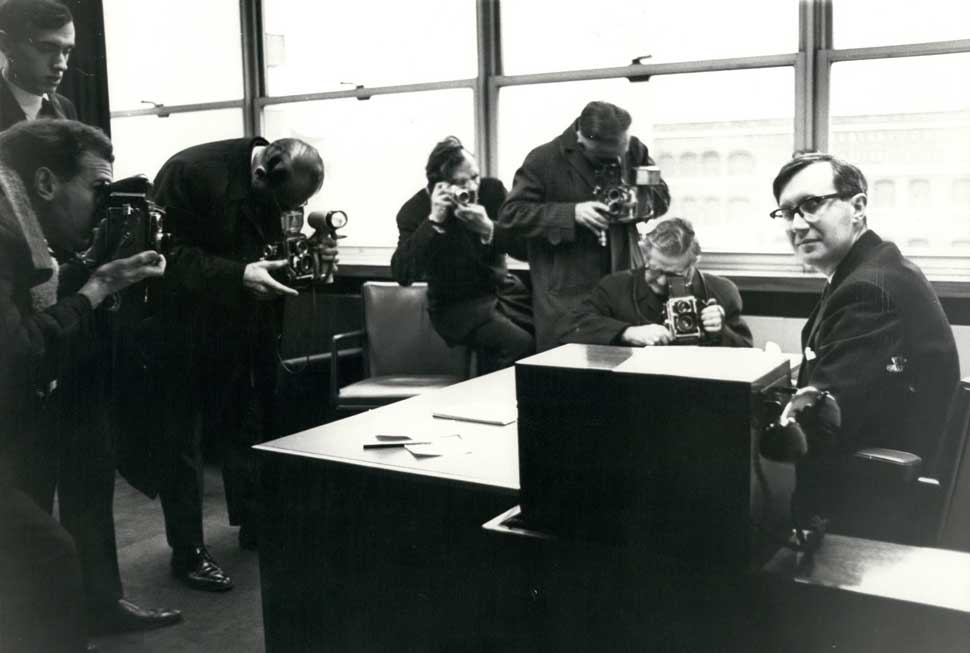

His sudden reprieve came after The Times printed an editorial, penned by its editor William Rees-Mogg (yes, dad of similarly louche, Rabelaisian figure and modern day Tory MP Jacob), entitled Who Breaks A Butterfly On A Wheel? The leader column questioned the justification of sentencing Jagger (and Keith Richards, who had also been jailed on the even more flimsy grounds that he had allowed people to smoke marijuana in his home) to a prison term for the most minor of drug possession offences.

“Mr Jagger’s is about as mild a drug case as can ever have been brought before the courts,” Rees-Mogg wrote. “There must remain a suspicion in this case that Mr Jagger received a more severe sentence than would have been thought proper for any purely anonymous young man."

Rees-Mogg’s words seemed to have an instant impact, though. Within hours of that day’s edition rolling off the presses, Jagger was out of prison, his sentence replaced with a 12-month conditional discharge. But other media cogs were also rolling at a speed more associated with the 21st century than the late 60s: ITV’s flagship current affairs programme World In Action had somehow arranged for Jagger, on the same day he was released, to be flown to a secret location by helicopter for a televised interview – helmed by Rees-Mogg himself.

So viewers were treated to the surreal sight of a kaftan-clad Jagger landing in the back garden of a stately home in Essex, where the TV voiceover informed us he would meet, along with Rees-Mogg, Father Thomas Corbishley (“a leading British Jesuit”), Lord Stow-Hill (former home secretary and attorney general) and Dr John Robinson, Bishop of Woolwich (“author of a controversial reassessment of Christianity, Honest To God”), sat in a row on in the garden as what Rees-Mogg referred to as a “bench full of the establishment”.

“It was quite mad,” Jagger said later. “Impossible to satirise. Why was I doing that? It was the day I got out of prison. I was absolutely hopeless on that programme.”

Stones fans might have been a little startled to hear Jagger, his estuary vowels polished up, saying things like “One doesn’t ask for responsibilities, one is given responsibilities when one is pushed into the limelight in this particular sphere.”

He went on to explain to his inquisitors, keen to impress on him his responsibility to present a good example to his impressionable young fanbase: “I don’t want to generate a new code of living or code of morals, I don’t think anyone in this generation wants to…”

He added – possibly digging at The Beatles: “I don’t propagate religious views such as some pop stars do, I don’t propagate drug use…”

Meanwhile, by way of explaining something about the generation gap, Jagger waffled:

“Today one’s faced with a very different situation than in past centuries because of communications… instant communication… which makes this generation very different to the others”.

He went on to defend Timothy Leary and even try to explain the US race riots (“not so much a colour thing… a rebellion against the whole system”), but ultimately attempted to explain young people’s desire for freedom from the stuffy old rules set by the people sat before him.

The panel listened politely – respectfully, even – and even if his words probably had little effect, and were hardly expressed very eloquently, the interview itself seemed to mean something more than any words either party had to say.

The establishment had realised they had to come to terms with this seismic cultural shift, and talking to Jagger – who had briefly been caught in the crossfire – was one way of trying to do that.