On April 18, 1972, Genesis play The Piper Club in Rome. A TV crew interview the group backstage before filming them performing to an audience of rapt Italians. Despite Steve Hackett’s Zapata moustache and Phil Collins’ Dickensian sideburns, everyone in the group looks impossibly young. There’s boyish Peter Gabriel with a triangular chunk shaved out of his centre parting; there’s an even more boyish Tony Banks, wearing a pensive expression and a sensible jumper; and then there’s Mike Rutherford.

The guitarist/bassist flashes a lazy grin from behind lank curtains of hair. “We like audiences that, uh, sit down and listen to the music,” he announces, “rather then, uh, get drunk and pick up girls.” “Big ones,” interjects Phil Collins. “Yuh, big ones,” agrees Rutherford, to a chorus of giggles and another lazy grin.

In April 1972, Michael John Cloete Crawford Rutherford was 21 years old. “And there I was,” he says now, “with long hair and a double-neck guitar, hanging out with Phil Collins and Tony Banks. When my father was 21, he was fighting a war and sinking the Bismarck.”

The polarity between Mike Rutherford’s life and that of his late father, Royal Navy Captain William Rutherford, is the thread that runs through his autobiography, The Living Years. It’s a revealing account of his life and times in Genesis, spliced with extracts from his father’s unpublished memoir about “an age of empire, of archdukes, emperors, and a map of the world that was coloured pink”.

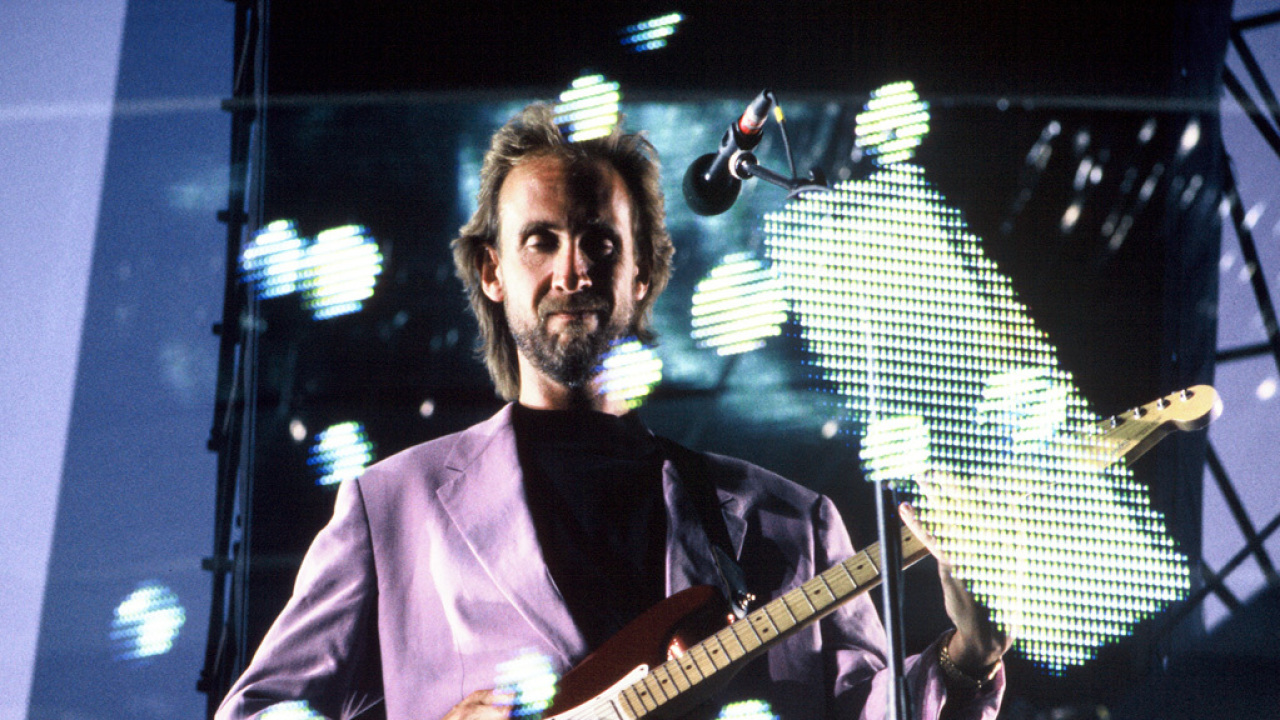

The Mike Rutherford that strolls into his management’s Kensington office this December afternoon is a far cry from the 21-year-old in The Piper Club. The curtains of hair are long gone and the once boyish face is concealed behind the beard he’s been wearing, in varying degrees of wooliness, since Wind And Wuthering. The 63-year-old Rutherford laughs easily but also exudes the same quietly posh, brisk air that runs through The Living Years.

The starting point for this memoir was the death of his father in October 1986. Genesis were on tour and Rutherford flew home from Chicago for the funeral, then straight back to play the LA Forum. The band were at the height of their global powers and there was no time to grieve. When his mother died in 1992, Rutherford moved three of his father’s trunks into the attic above his studio, where they remained, unopened, until three years ago. By then, both Genesis and Rutherford’s side-project band Mike + The Mechanics had come to an end. “I didn’t want to open them before that,” he says. “But I was having a slow writing day in the studio and just decided to do it.”

In the first trunk he found his grandfather Nathaniel Rutherford’s two books about life as an army doctor. In the other two were his father’s papers and files, including his unpublished manuscript about his time in the navy. “There was

”There was a rejection letter with the manuscript that said: ‘Terribly sorry Mr Rutherford, but there isn’t much demand for books about naval history in this day and age…’ So there was a legacy there that I wanted to address. I wanted to see bits of my father’s book in print.”

Part of what spurred Rutherford to write this memoir was the contrast between his life and his father’s. “When you look at early photographs of us, it’s like looking at the same person – prep school, the football team. Then suddenly our lives diverged.”

The road to Genesis began when Mike Rutherford enrolled as a pupil at Charterhouse public school in Surrey in the summer of 1964. By then his parents had bought him a guitar and taken him to see Cliff Richard And The Shadows at the Manchester Apollo. The die was already cast.

“I was born at just the right time,” he explains. “My parents’ generation were in shock and worn out after the war. Then along come The Beatles, the Stones and blue jeans. Suddenly young men had their own music and clothes, and didn’t want to wear cavalry twills like their fathers. It was a huge social change and I was in the thick of it.”

At Charterhouse, Rutherford met guitarist Anthony Phillips, and passed through two school groups, The Anon and The Climax, despite being banned from playing guitar by a housemaster who considered the instrument “a symbol of the revolution”.

The Living Years is especially good at conveying what it was like growing up in an English public school at a time when pop music was considered a subversive influence. “I try and explain this to my kids,” says Rutherford, laughing. “They say they get what I’m talking about, but they don’t. You cannot imagine the excitement of hearing a new Beatles record. After Sgt Pepper in 1967, it was a blank canvas – anything was possible.”

By this point, Rutherford had become Charterhouse’s resident rebel, if a rather genteel kind of rebel. He grew his hair, smoked cigarettes, puttered around the Surrey countryside on a Honda 50 in defiance of a school rule that banned pupils from owning a motorcycle, and skived off to see bands like The Nice and Cream at The Marquee.

“I’d park the Honda at Guildford station, then get the milk train back from London at 5.30 in the morning.”

Genesis came together when Rutherford and Phillips met two older pupils playing in a group called Garden Wall. There was “edgy, nervy” piano player Tony Banks, and drummer, pianist and singer Peter Gabriel, a boy who “made his own hats and tie-dyed T-shirts in sinks”.

With the patronage of former Charterhouse pupil-turned-producer Jonathan King, they changed their name to Genesis and recorded their debut album, From Genesis To Revelation, in August 1968. “We wanted to be original,” writes Rutherford, “but Jonathan didn’t like our sort of originality.”

The album sank but, incredibly, Captain Rutherford allowed his son to pursue a career in music rather than take up a place at Edinburgh University. Rutherford Senior and the other band members’ parents apparently donated £200 each to spend on musical equipment. It was a magnanimous gesture from fathers who must have wondered whether they’d just squandered an awful lot of money on their sons’ education. There’s a lovely scene in the book when a teenage Rutherford rocks up to his dad’s gentlemen’s club for a chat about his future, wearing mauve platform boots and an Afghan coat, which he hands to the club’s appalled doorman.

“My relationship with my father was a little troubled in the early days,” he admits. “But he was also incredibly supportive. It’s hard to imagine how he must have viewed it because he had nothing to compare it to. We were the first generation of rock’n’roll musicians. It was like I was venturing off into the deep unknown. Later on, he and my mother used to turn up to lots of Genesis shows. He wanted to understand it.”

Genesis spent winter 1969 in Christmas Cottage, a property owned by their friend and roadie Richard MacPhail, in Dorking, Surrey. According to The Living Years, best friends Gabriel and Banks bickered constantly, and drummer and carpenter John Mayhew was “better at carpentry than drumming”. But it was here that they wrote most of what became the first proper Genesis album, Trespass.

Rutherford thinks the physical isolation helped them discover their sound. “Peter and Tony had carried From Genesis To Revelation – that was all them,” he explains. “It wasn’t until we spent six months in the cottage that we came together as a band. We had two LPs, In The Court Of The Crimson King, and a Moody Blues one, Days Of Future Passed. That was all we had to listen to. Had we been in London and going out to see bands every night, we would have sounded different. Stuck in that cottage, there were no distractions. We were on our own.”

But what Rutherford calls the “folky, fanciful” music of Genesis was a hard sell. It became harder still when Ant Phillips left. Genesis had signed to the forward-thinking Charisma Records label and had just released Trespass. Phillips’ timing couldn’t have been worse. “It was the biggest shock at the time,” says Rutherford.

In the memoir, Phillips’ departure seems to have been a bigger deal than even Peter Gabriel’s four years later: “Ant had some sort of virus that really knocked him out. But he also had stage fright. That was the first thing I learned doing this book. I asked myself, why didn’t we just say: ‘Okay chaps, how about taking three months off?’ We shouldn’t have just let him leave. But we were too young and didn’t know how to deal with it.”

Rutherford portrays Phillips as the band’s unsung hero: “I would like him to come across like that, because he was the unsung hero. He was the driving force of Genesis in those early days, and people really don’t know that.” That said: “Getting past the first person leaving was the hard bit. After that it became easier.”

Captain Rutherford was a man who served his country and did his duty without question. His son shared his ability to make the best of any situation. Sent away to boarding school (“a world of dormitories and cold morning baths”) at the age of seven, this tough regime continued at Charterhouse. Going from sleeping in a ‘cube’ (“a ceilingless cubicle which at least allowed privacy when masturbating”) to a cramped tour bus was no great leap. “We’d been beaten down [at Charterhouse], and got used to living quite basically in a tough environment.”

Rutherford, Gabriel and Banks were well equipped for life in Genesis. Where the two non-Charterhouse band members fitted into all this becomes clear in The Living Years. Phil Collins replaced John Mayhew in 1970 and immediately lightened the mood. In fact, you can’t get a bad word out of Rutherford about Collins: “Phil was very comfortable straight away. He had this upbeat, happy, joker element. He was so good for us.”

However, Phillips’ eventual replacement, Steve Hackett, had a tougher time. “I think it’s no coincidence that the other guys found Steve when I was ill in bed with a stomach ulcer, because I probably would have tried to find another Anthony,” Rutherford admits. “And that was not the right way to go. Once Steve came along, I enjoyed what he did, but I would still be saying: ‘Not quite right there’.”

Hackett once told this writer that in Genesis’s early days, he and Collins would watch Rutherford, Gabriel and Banks arguing, and believed that the root of those arguments was something that had happened in their schooldays. Rutherford admits that the rows were so bad that when Collins first witnessed one: “Phil was convinced the band was splitting up.”

But he insists that their shared background kept them grounded. “Listen, when you’ve all been in shorts together, nobody can get away with any airs and graces.”

Rutherford depicts Peter Gabriel as a gifted songwriter who drives his bandmates mad with his tardiness and dithering. But his anecdotes about Tony Banks are spikier. When Banks refuses to play an encore at an early gig in Hemel Hempstead, Rutherford threatens to hit him with a chair.

“I then kicked him all the way back to the stage,” he writes. Banks comes across in the book as a brilliant musician, but pernickety, unadventurous and incapable of writing hit songs.

“It’s true,” says Rutherford, grinning, “about the hit songs. He has a problem with words. Who else but Tony would use the words ‘sheets of double glazing’ in a song [from Domino]?”

Is Banks likely to be offended? “There are things I will say in front of strangers about Tony that I will happily say to his face with a certain tone,” he replies. “But I know it can look harsh in print. I got [Genesis manager] Tony Smith to read the manuscript with that in mind. He took out a couple of digs at Tony. But it’s not that bad. Tony can take it.”

Has he sent his old bandmates copies of the book yet? “I sent one to Pete and Phil today. Not Tony yet, no,” he adds, grinning. “I prefer to keep winding Tony up. I’m telling him: ‘I don’t want to send you a copy now and ruin your Christmas.’”

It was Rutherford, Banks, Gabriel, Collins and Hackett who recorded that run of imperial progressive rock albums, beginning with 71’s Nursery Cryme and ending with 74’s The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway. Rutherford writes fondly about the era, but isn’t afraid to criticise: “For Absent Friends [on Nursery Cryme] was Phil and Steve’s song, and I could have done without it on the record… Watcher Of The Skies [on Foxtrot] was a prime example of the fact that you can write great lyrics that read well, but are hard to sing…”

Genesis devotees will find plenty of pub trivia to pick over in Rutherford’s book. Squonk (from A Trick Of The Tail) was, apparently, inspired by Led Zeppelin’s Kashmir; Tony Banks was annoyed when Brian Eno played on The Lamb… as he thought fans might presume it was Eno playing all the keyboards; and Rutherford considers his own composition, the Gary Numan-inspired Man Of Our Times, the worst song on Duke.

“Supper’s Ready is still special,” he says. “That’s my favourite long Genesis piece. Writing this book, the more I thought about Supper’s Ready, the more I realised that. But you can’t keep doing Supper’s Ready forever.”

Rutherford also doesn’t shy away from that fact that the early Genesis stagecraft left a lot to be desired. The problem was, most of the band, not just the audience, sat down. On one occasion, Rutherford nodded off on his stool. “I came round after a moment or two and looked about to see if anybody had clocked me – no one had.”

Even Charisma’s press officer once called the band “fucking boring”. Ultimately, it was Peter Gabriel that brought Genesis’s “folky, fanciful” music to life by painting his face and wearing increasingly outré costumes on stage. “And it worked,” says Rutherford, “because suddenly we were on the cover of Melody Maker.”

While Gabriel’s ambition drove Genesis forward, it also drove him away from the band during the making of The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway. It’s the 40th anniversary of The Lamb… this year. There’s a framed print of the album artwork hanging on the wall of the management’s office. Rutherford glances up at it as he speaks.

“The Lamb...’s not a favourite of mine, but it’s a brave album,” he offers. “The trouble is, when you’re in a band, your opinion of an album is always coloured by the making of it. That one wasn’t much fun. Pete left, then came back, then left after the tour. There’s some stuff on that record that I’m very proud of, but it’s a disturbed album.”

In The Living Years, Rutherford expresses regret over Gabriel’s departure, while admitting the rest of the band did nothing to prevent it. “Again, we could have said: ‘Let’s take three months off’. But, looking back, Pete was always going to leave.”

Really? “Yes. Being in a band, any band, is a compromise. Musically, Pete was moving forwards a bit braver and faster than we were. So he was starting to feel constrained.”

It seems that Captain Rutherford was more upset than his son about Gabriel leaving the band. “That Pete could jump ship made dad a bit angry.”

But, once again, that old public- school stoicism came to the fore. “When Pete left, we thought: ‘Oh fuck‘. But then we thought: ‘Look at all these songs written by me and Tony’. That was the problem – the audience thought Pete wrote all the songs. He didn’t.” The four-man Genesis kept writing songs: “However, we realised they could get a bit boring without any vocals.”

Enter Phil Collins from behind the drum kit – though it took a little time for Rutherford to be convinced that he was the man for the job. At his first gig as lead vocalist (in London, Ontario, March 76) Phil arrived on stage holding a sheet of paper on which he’d written things to say to the audience inbetween songs. His hands – and the paper – were shaking. “At that first show, there was a while when I was thinking: ‘What the fuck is this?’.” Rutherford admits. “Then, after about 40 minutes, I thought, ‘This is gonna work‘. But there was some trepidation.”

The next album, 1976’s A Trick Of The Tail, proved that Genesis could survive without Peter Gabriel. According to The Living Years, it was only now, after a six-year cycle of album, tour, album… that Rutherford came up for air and married his girlfriend, model Angie Downing. The two had been friends since they were 17. Why did it take so long? “We were away so much in Genesis and she was away so much as a model, the timing wasn’t right.”

In the 2008 Genesis documentary, Come Rain Or Shine, Mrs Rutherford complains that her husband is a “dreadful mumbler”. Perhaps it’s because the conversation has shifted from music to personal relationships, but Rutherford’s having a bit of a mumble now. “Because we had been friends for so long, it’s hard to become lovers,” he says, explaining his Gabriel-style dithering. “So I had to choose my moment with Angie, because if it had gone wrong, that’s everything fucked.”

Before then, Rutherford had thoroughly enjoyed the perks of life in a touring rock band, though it had its pitfalls. In the book he recounts an incident in Pittsburgh on Genesis’ 1974 tour, where he ends up drunk on Southern Comfort, naked from the waist down and blindfolded in his hotel room. Unfortunately, his female companion shuts his hand in the bathroom door, and Rutherford has to play the following night’s gig with a splint on his fretting finger.

In fact, Genesis’s staid image is shot down several times in Rutherford’s memoir: “I read Keith Richards’ book [Life], and there’s no way I could compete with that,” he says. “But we had our moments.”

These moments include Rutherford getting busted at Heathrow Airport with a “huge bag of grass” he’d forgotten about in his luggage, and poor Angie getting strip-searched after customs officers find a joint her husband has absentmindedly left in her bag.

Did the drugs ever become a problem? Rutherford points to his nose. “I had to have my septum operated on in the late 70s,” he says, matter-of-factly. “Yuh, you know, that bit in the middle of your nostrils.”

Apparently several years of cocaine use had taken its toll on the membranes. “This was pre-social, though, pre-social,” he insists. “Cocaine was simply taken as a way to keep you going on the road. Never by Tony or Pete, though.” In fact, Rutherford has a theory that the rock’n’roll lifestyle was never a problem for Genesis, simply because they were English. “It’s true,” he says. “Not many American bands last as long as English bands because they believe the dream, and someone’s always telling them they’re wonderful. When I came back off tour, I used to go to the local pub and everyone ignored me.”

Rutherford’s description of himself in his personal relationships as “a bit slow getting there emotionally” could easily apply to Genesis. With Phil Collins fronting the band, Genesis started to write about real life and real emotions, rather than man-eating plants and alien visitations.

A Trick Of The Tail’s follow-up, Wind & Wuthering, included Rutherford’s first love song, Your Own Special Way. Genesis were evolving, and Rutherford is well aware that not all of their audience were evolving with them.

“I know that some punters felt a bit annoyed when we went from, say, The Return Of The Giant Hogweed to Your Own Special Way. But we couldn’t keep doing …Hogweed. We weren’t aiming anywhere, we were just travelling, and …Special Way is where we ended up.”

Steve Hackett walked out of Genesis in 1977 while they were mixing the live album, Seconds Out. In the book, Rutherford reveals that Hackett was absent for the first few days of writing for A Trick Of The Tail. By the time he arrived, the other three had come up with Dance On A Volcano and Squonk without him. Hackett had been busy with his first solo album, and Rutherford expresses some annoyance that he hadn’t been keeping his best material for Genesis. But Hackett’s departure is the one that Rutherford seems the most conflicted about.

“Steve needn’t have left,” he insists. “I could have seen Genesis staying as the four of us. I don’t know why he left. Then I read some stuff in [the official Genesis biography] Chapter And Verse about how there were some things he wasn’t happy about, and I thought: ‘What a shame. I didn’t know. Why didn’t we talk about it?’.”

But there was another problem besides poor communication: seven years on, Ant Phillips’ replacement was still struggling to find his place as a songwriter. “There were already three songwriters in Genesis, and that was tough to break into,” Rutherford admits. “We were three tough old motherfuckers.”

That statement alone encapsulates Mike Rutherford’s mindset. When he talks about Genesis, he’s invariably referring to himself, Banks and Collins, even when discussing the old days. Both in conversation and in his memoir, it’s obvious that the three-man Genesis is the one Rutherford most relates to. Not that this stopped him making records without the other two.

In 1981, Rutherford released his first solo album, Smallcreep’s Day, based on Peter Currell Brown’s novel about a bored factory worker. Were there parallels with his life in Genesis? “I liked the story, and there’s always going to be a part of you that thinks: ‘Is this it?’ when you’re in a group. We all made solo albums to further our musical knowledge, and it worked. We were stronger when we came back to the band.”

Nevertheless Rutherford regrets his decision to sing lead vocals on his second solo release,1982’s Acting Very Strange.

“It was something I had to do once, but never again.” Apparently, Captain Rutherford heard the album and politely suggested his son “didn’t give up the day job”.

Genesis were in the middle of recording Abacab when Phil Collins’ debut single In The Air Tonight came out in January 1981. Rutherford must have felt a twinge of jealousy. “Yeah,” he says, laughing. “Number Four in the first week? Fortunately we were in the studio together, so we could talk to Phil about it. Had we not been, we might have found it harder to deal with.”

Rutherford admits that Collins might have played him and Banks a demo of In The Air…, but that it probably didn’t make an impression because “we were such chord snobs and it only had three chords”. Today, though, he decides to blame Tony Banks. “I can imagine Tony dissing it,” he adds mischievously, “and saying [slips into an eerily accurate Tony Banks impersonation]: ‘What else you got? Come on’.”

For Rutherford, the Hugh Padgham-engineered_ Abacab was Genesis’s breakthrough album: “Hugh helped to make us sound as powerful in the studio as we did live.” But tracks such as the “sonically bizarre” Who Dunnit?_ proved too much for some. Rutherford writes about the band playing the song in Holland and getting booed by a “bunch of old Dutch hippies”.

But Rutherford regards the first vinyl side of the follow-up, 1983’s Genesis, as the band at their peak. “After [1980’s] Duke we’d got into a bit of a rut,” says Rutherford, “On Genesis we went back to the band writing together again, and that’s when it works best.”

There were long songs to appease the old Dutch hippies (Home By The Sea, Second Home By The Sea) and the sonically bizarre hit single Mama, which was apparently inspired by hip-hop pioneers Grandmaster Flash’s The Message. It’s obvious Rutherford still loves that album. The only fly in the ointment was the sleeve.

“Crap cover!” he exclaims. “But the best of a bad lot. You should have seen the other suggestions. Awful.”

With 1986’s UK and US Top 5 album Invisible Touch, Genesis became MTV darlings and global superstars. Rutherford spent these years wearing a loud shirt, leather trousers and a light perm, zooming between time zones on Concorde. According to the book, everyone in Genesis became slightly disconnected during this period, especially the once happy-go-lucky Phil Collins, who developed an on-tour ritual of obsessively re-packaging his designer T-shirts in their cellophane wrappers after each wash. “I’m sure it was a coping mechanism,” Rutherford writes.

But Rutherford doesn’t explore Genesis’ stadium years in half as much detail as what’s gone before.

“Once you get into that big arena touring in the 80s and 90s, there’s less to say. It’s not so unique any more.” By then, Rutherford had also carved out a successful side career with his own group Mike + The Mechanics. The Living Years gives more space to the Mechanics than it does to the Genesis of We Can’t Dance, or their swansong album, Calling All Stations.

When Phil Collins finally left Genesis in 1996, Rutherford and Banks battened down the hatches again, and surprising to many hired Ray Wilson, the then 28-year-old vocalist with hard-rock band Stiltskin. But the subsequent album and tour sold relatively poorly.

“There was no glue,” says Rutherford. “I didn’t realise until Phil left how much he was the musical glue between me and Tony. Ray wasn’t a writer, and I think if we’d wanted to carry on Genesis we would have needed to find another writer.”

Banks wanted to continue, but Rutherford couldn’t face “three or four years of album, tour, album…” to re-establish Genesis: “I felt the hill was too high to climb.”

Although Genesis ended with less of a bang, more of a whimper, Rutherford, Banks and Collins reunited for a tour in 2007. Rutherford and Banks thought they were re-forming the five-man line-up, but when they sat down for a band meeting, they discovered that the ever-dithering Peter Gabriel was only there to “discuss discussing the tour we might be going to do”. Exit Gabriel, quickly followed by Steve Hackett. Once again, the “three tough old motherfuckers” were the last men standing. “The weird thing is, when you put Phil, Tony and me in a room, we are the band again.”

In February Rutherford heads back on the road with a revived Mike + The Mechanics. Could it be a precursor to another Genesis reunion? “I can’t see us making another Genesis album,” Rutherford says straight away. But in August last year, he Banks and Collins met for dinner. “So I’d never say never to playing live again.”

Writing The Living Years could have been Rutherford’s way of drawing a line under his musical career, but it seems it isn’t. Not yet, anyway. “You can’t necessarily retire from music,” he says emphatically. “If you’re going to retire, you have to have a back-up plan.”

Prog’s photographer has now arrived, and Rutherford points to a large black case on the floor outside the office. “See that?” he says, “I’ve got the old double-neck Rickenbacker in there for when we do the pictures.”

And with that, he’s up, rubbing his hands together excitedly and striding off towards the door. Suddenly Mike Rutherford almost looks 21 again.

This was published in Prog issue 43

Read Anthony Phillips’ feelings on a Genesis reunion

Here’s a Buyer’s Guide To Genesis

Here’s a Q&A with Rutherford