For a brief moment in the late 80s, the Misfits were just about the coolest band on the planet. It was 1987, and Metallica had covered two of their tracks, Last Caress and Green Hell, on their Garage Days Re-revisited EP. This cult punk band from working-class New Jersey were suddenly the name on every on-trend metal fan’s lips. The fact that they’d split up several years earlier was neither here nor there.

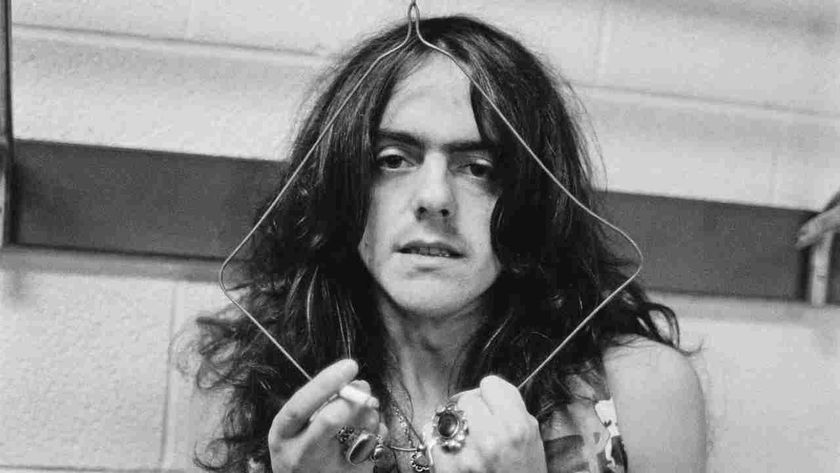

Their B-movie-style black-and-white logo and iconic skull mascot was emblazoned on t-shirts from London to LA. Their distinctive ‘devil-lock’ haircut – a grown-out quiff greased to a point down the front of the face – became the haircut de riguer among more outré metal-heads. Everybody loved the Misfits, even people who’d never even heard them. And, Metallica covers aside, there were a lot of people who’d never heard them.

“Our skull was better known than our name, and that was better known than our music,” says bassist/frontman and sole remaining founder member Jerry Only in an accent thicker than tarmac. “But Metallica kept us alive and helped us grow at a time when that should never have happened. Even now, kids run up to me and say, ‘Oh, you got wristbands like Metallica!’ ‘Yeah, right kid…’”

In their original incarnation between 1977 and 1983, they recorded three landmark albums plus countless EPs and singles that single-handedly kickstarted that gloriously twisted micro-genre, horror-punk. Their music – a darker, bloodier take on the Ramones’ 50s-indebted bubblegum punk – and their look – be-muscled gravediggers glowering out from under ‘devil locks’ – would influence bands from Metallica and GN’R, to AFI and Slipknot, through My Chemical Romance and Black Veil Brides (but don’t hold that against them).

“When you went into New York, everybody was shootin’ dope,” says Jerry. “It was a heavy narcotic scene. I wasn’t about that. That’s why we came up with the horror thing. We loved horror films, sci-fi, B-movies. We weren’t drug-shootin’ beatnik Bowery Boys.”

The Misfits had been spawned in February 1977, in Lodi, New Jersey. While it was hardly a hotbed of rebellion, it was close enough to New York to pick up the Big Apple’s cultural overspill. Eighteen-year-old high school athlete Jerry Caiafa had been introduced to punk rock by casual acquaintance Glenn Anzalone, three years older. Within a few weeks, Jerry had picked up a bass and Glenn had adopted the stage name Danzig, after the first Polish town to be invaded by the Nazis.

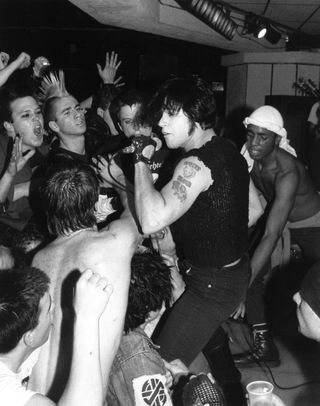

They didn’t know it at the time, but the Misfits would be the bridge between the US punk scene and its younger, gnarlier brother, hardcore. They muscled onto bills at CBGBs, the ground zero of New York punk; they’d take the stage at 3am to a roomful of strung-out scenesters. Their very first album, Static Age – an instant classic recorded in 1978, but criminally unreleased until 1997 – was buzzsaw punk-pop drenched in fake blood.

As time progressed, punk rock toughened up and so did the Misfits, shifting up gears on 1981’s peerless Walk Among Us (the second album they recorded, though the first to be released, and the first with Jerry’s brother Paul ‘Doyle’ Caiafa on guitar) and flooring the accelerator on 1983’s 15-minute thrashpunk explosion Earth A.D./Wolfs Blood.

“We were something ya couldn’t cage,” says Jerry. “Our shows got crazy. You’d get skinheads jumping around, beating the crap outta each other in front of the stage.”

But all things good and bad must come to an end. The last Misfits show took place in Detroit on Halloween 1983. “Glenn was like, ‘I can’t work with the drummer, I quit.’ I’d been working in my dad’s machine shop, paying for the band. I was like, ‘Well, that told me.’ Glenn wanted to do his own thing, but I wasn’t into that Son of Satan kind of thing.”

Following the split, Danzig formed the more overtly occult-themed Samhain, who mutated into his own hugely successful eponymous band. Jerry went back to work in the machine shop. “I’d go in at 6am,” he says. “We did some military work around Desert Storm [in the original 1991 Gulf War], so I was working 18 hours a day.”

The late 80s and early 90s was a strange time for the Misfits. They were more successful than they’d ever been, thanks to covers by Metallica and GN’R (who tackled Attitude on 1993’s The Spaghetti Incident), but as a band they were deader than Bela Lugosi’s doornail. The rich pickings prompted a legal battle between Jerry and Glenn, settled in 1995 when the bassist bagged the rights to the Misfits’ name and the singer got the publishing rights.

Throughout this time, there was another, more subtle battle raging for the Misfits’ soul. Prompted by Metallica’s cover versions, metal fans now claimed them as their own, to the annoyance of the band’s original followers, who saw them as an exclusively punk proposition.

While Danzig pursued his ‘Evil Elvis’ fantasties, Jerry and Doyle successfully alienated any remaining hardcore fans by forming an ill-fated metal band with ex-Yngwie Malmsteen wailer Jeff Scott Soto called Kryst The Conqueror. They recorded a full album of messy, technical metal, though only a five-track EP saw the light of day.

“It was as far away from the Misfits as you could get,” he says with a mixture of pride and embarrassment. “We wanted Bruce Dickinson to sing. Dave Sabo from Skid Row played lead on the album. We had one song, March Of The Megamites, that was six minutes and 58 seconds long and it never played the same thing twice.”

Were you embarrassed by the Misfits?

“Nah, but I didn’t want people to put the skull and songs together in a negative way. Kryst The Conquerer was more of a cultural statement: ‘The guys from the Misfits, we’re not bad.’”

Kryst, Christ… are you a religious man?

“Well, I grew up very much so,” he says cagily. [Pause] I’ve had experiences where I feel you kind of touch the other side and realise that it’s there. Look, I don’t push it on anybody. God’s different for everyone. That’s the beauty of God.”

And when was the last time you saw Glenn?

“We spoke when we first got the name back. That was the first thing we did. We said, ‘Hey, do you wanna bury the hatchet and do something?’ He said no. But we gave him that opportunity.”

Jerry Only is as tough an old bird as you’d expect a former high school football player who could once bench press 200 kilos to be. But he’s had no choice. The singer he called in to replace Glenn for 1997’s comeback album American Psycho was Michale [sic] Graves, an ex-Marine and diehard Misfits fan. “I picked a young singer, 19 years old, to be the new face of the band,” says Jerry. “In the beginning, he was there all the time. Then as time went by, he never showed up at all. That was disrespectful. He was two years old when I started the band.”

Exit Michale after 1999’s Famous Monsters, followed by Jerry’s guitarist brother, Doyle.

“He ran into a girl who was [wrestler] Macho Man’s girlfriend,” sighs Jerry. “She’s an exotic dancer, but I guess the other word would be stripper. He wanted to add her to the band. She was, like, ‘I’m gonna write songs and dance onstage.’ I was, like, ‘Not in this band you’re not.’ So my brother decided to go with her.”

Doyle still works in the Caiafa family business and the brothers say hello when they see each other. The guitarist occasionally plays with Glenn, although never under the Misfits name. Does Jerry ever feel excluded from their party?

“Nah, I wouldn’t wanna do that. I’d be an actor. I’d be Marlon Brando in Apocalypse Now.”

Ask Jerry if he listens to the bands he’s influenced, and his answer is exactly what you’d expect from a man who’s spent 30 years working in a machine shop in New Jersey.

“Hey, I just do my thing,” he says, which is a neat way of saying, ‘I’m 52, why in the name of Satan’s arse would I listen to new music?’ “If I stick my periscope up and look around, then I’ll get influenced by other things that are going on around me, which is something I don’t really wanna do. I wanna keep this our vision.”

And there’s no arguing with a vision that has served him intermittently well for three decades. The band’s latest album – featuring a reluctant Jerry on vocals and former Black Flag man Dez Cadena on guitar – may lack the youthful fire, but it keeps the Misfits’ brand values admirably intact. There are no songs about banking crises or world terrorism here, just 14 bursts of Hammer House Of Horror-goes-punk noise with titles like Death Ray and Curse Of The Mummy’s Hand.

“We don’t have any real world spaghetti sauce,” he says. “We’re a horror outfit, a sci-fi outfit. We’d never bring our level of insanity down to the real world.” He sounds disgusted by the idea. “I don’t think we have any business being there.”

Once a misfit, always a misfit.

This article originally appeared in Metal Hammer #225.

For more on the Misfits, not least Andy Biersack’s favourite tunes, then click on the link below.