“This is the birthplace of globalisation,” Moonspell bassist Aires Pereira quips. Aires is pointing at a monument on the estuary of the Tagus River as the Portuguese quintet guide Subterranea around their hometown of Lisbon. Two columns mark the great Portuguese explorers who, 500 years ago, set sail to discover the New World.

It’s a tongue-in-cheek comment – and an ironic one, given the bandmember making the joke is originally from Venezuela, and plays in a Portuguese band whose drummer spent the early part of his life in Massachusetts – but it highlights a few things that have gone into making Moonspell the band they are. Portugal may now be thought of as a sunny holiday destination, a place to enjoy sangria and seafood, but once it was both the edge of the known world and one of the great imperial, colonial powers of its age. No longer. A microcosm of more recent history is happening just behind us as Aires notes.

Over our shoulders, in the Praça do Comércio (Commerce Square), the fireman are protesting, loudly. This district of Lisbon helped regulate the finances of Portugal’s colonies across the world. The square also saw the assassination of the penultimate king of Portugal in 1908, two years before the abolition of the monarchy. So in a city that once helped rule the world, but no longer does, the age of austerity is seeing yet another set of public sector workers in opposition to their lot. In essence, great history is flung together with a painful modernity that is not the brave new world those who came before envisioned.

What has this got to do with Moonspell, though? Over sangria and seafood (when in Rome…), the band’s frontman sums it up.

“To understand Moonspell throughout the years, the place where we come from, Portugal… everyone thinks it’s such a solar country, but in fact it’s a melancholic country,” says singer Fernando Ribeiro. “I believe that all our career is influenced by the fact we are Portuguese, hands down, and every year that passes, I find it more and more evident.”

Moonspell’s history is unique to them, but there are certain basic parallels with other bands. Debuting in the 90s, at a time when more traditional heavy metal was marginalised in favour of nu metal and the ‘alternative’ wave that followed Nirvana, they came from a country with little in the way of a metal scene, with few bands to look up to and no obvious audience. And yet they found popularity both within their homeland and beyond, and became flag-carriers for that nation’s metal.

This potted history could also be applied to (among others) Irishmen Primordial, while Rotting Christ come close in Greece, and India’s Demonic Resurrection, for a more recent example, have similarities. The differences quickly becomes apparent, though. All these bands may owe their existences to Tom G Warrior and Quorthon, but Moonspell’s path did not lead them through black metal – rather down a gothic avenue of their own, with more in common with Type O Negative than Taake. And yet the band have always been considered part of the underground despite a musical accessibility their cohorts lack, and a level of popularity unavailable to almost all their obvious peers./o:p

Walking around Lisbon, where the band can reliably sell out the roughly 3,000-capacity Coliseum, the band are frequently stopped and asked for photos by members of the public – both metallers and more conventionally attired fans. And yet this is a band whose first major tour was as support for Morbid Angel and Immortal, and in 2007 successfully headlined a bill in Vienna above Napalm Death and Behemoth – and focused on their most goth material, no less.

“I think we are kind of at a crossroads, where we are probably a little bit too underground and metal for some festivals, while being too mellow for others, which is a strange place to be,” Fernando says. “I’m sure this is something that we have to finetune with the new album, Extinct, but I don’t really have a problem, because I think that Extinct can be a guilty pleasure for some.”

“I remember being with Silenoz from Dimmu Borgir, and we were doing a re-release for our 1996 album Irreligious, which was a gothic album – there was some metal there, but it was more goth. I asked him for some quotes for Irreligious, and I was very surprised about his quote, because he said that it was a guilty pleasure for him, because he was in a black metal band and he didn’t want to get caught listening to a gothic record. I think time has, in a way, improved this; people are not so afraid –especially musicians and opinion-makers – to say, ‘Well, I’m a big death metal fan, but I love this new Moonspell album.’”/o:p

For all the problems and challenges the internet has presented to bands, this is one area that it has helped. In the past, the fact that most musicians and music fans listen to multiple different types of music wasn’t well-known, but the increased number of interviews freely available, and the use of social media, have let even the most hardcore of underground metalhead know it’s normal to like multiple styles. The stereotype of the stylistic elitist is fast becoming an anachronism – although in truth, it has probably always been an urban legend.

“We try to make music that can make the difference and take people out of their comfort zones,” Fernando continues. “I say that if a black metal fan listens to Extinct, we’ll have a chance, because of the musical quality and progression and what we did on the album. Sometimes it feels weird to bounce between the underground and the mainstream, sometimes we feel out of place: for instance, headlining Eindhoven Metal Meeting over Mayhem. But we still had more people listening to our songs and going for our songs, and we didn’t have to play our most black metal songs. We supported Slayer for a couple of shows, and we didn’t get any shit or ‘SLAYER!’ thrown at us.

“But there’s a lot of prejudice; sometimes, with our name ‘Moonspell’, people are crazy about it because it’s not ‘Behemoth’ or ‘Dying Fetus’. But I’m naïve and romantic about this. I was heavily into black metal and underground stuff – like Sarcófago and Genocídio, poorly recorded Brazilian stuff. I listened to Peter Murphy’s solo albums, and they were quite commercial, and that was never a problem. So maybe I’m naïve thinking that, for other people, that might not be a problem.”

Lisbon‘s Hard Rock Café features Moonspell memorabilia and their upcoming tour will again visit the Coliseum. Yet their visit to London’s 500-capacity Underworld on April 2 is a relatively tiny show for a band who fans of big acts like Paradise Lost and Type O Negative should love. Maybe like Rotting Christ: people judge the name and make false assumptions.

Some overlook Moonspell’s lush melodies, others ignore the band’s roots in black metal that give them a unique intensity, but their legacy of classic albums charts a unique and rich course through the realms of musical possibility.

EXTINCT IS OUT NOW VIA NAPALM/o:p

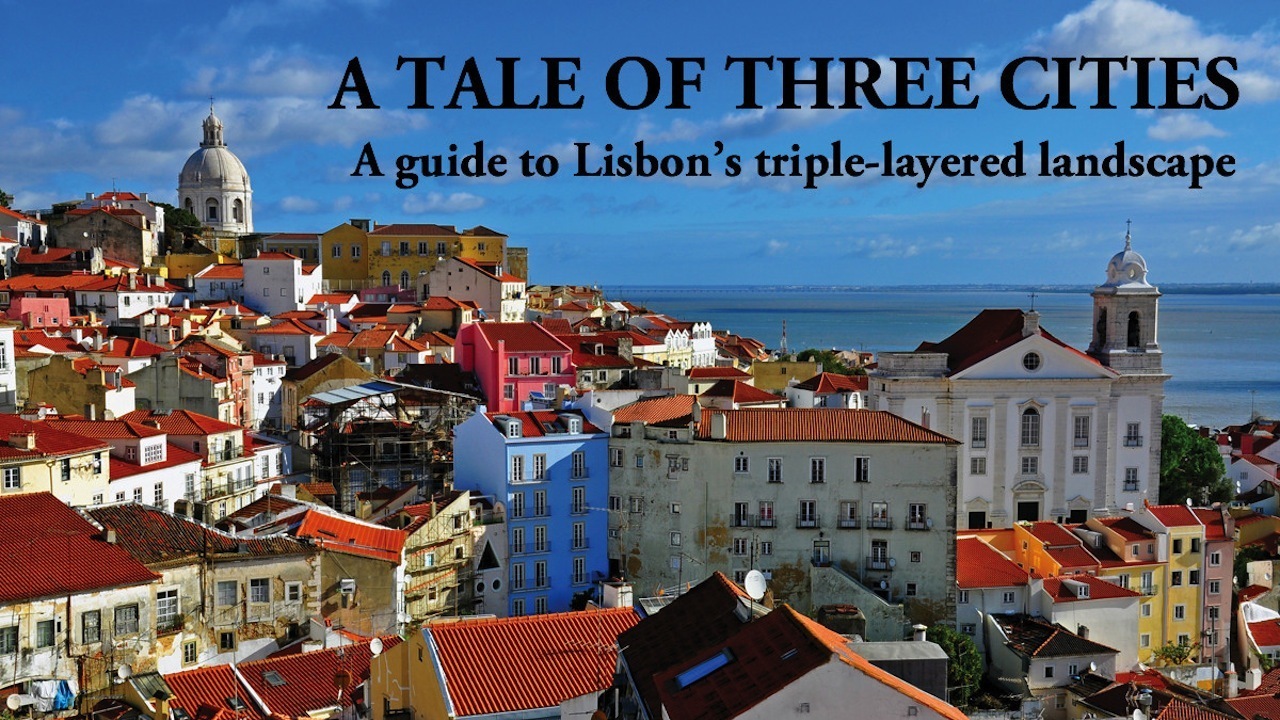

THE OLD OLD TOWN

The twisted, narrow streets of Portugal’s hills were one of the few parts of the city to survive its epic 1755 earthquake, and as such have the organic, unplanned feeling of Europe’s older cities – London, for instance. It’s dotted with ancient ginjinha (the delicious local sour cherry liqueur) kiosks and restaurants selling plenty of fish dishes.

THE NEW OLD TOWN

Rebuilt in the second half of the 18th century in imperial splendour, the grandeur of reconstruction favoured straight roads and broad boulevards that don’t require 20 years’ residency to be able to find your way around. The hills of Lisbon, including chapels and castles, loom all around.

THE SUBURBS

Lisbon remains a modern European capital city, and apartment blocks have sprung up all around the old town, but the most strikingly modern construction is in the Tagus estuary, where the 11-mile-long Vasco de Gama bridge crosses its huge width. Further down, on the south bank, a vast statue of Christ, visible for miles, stands on a plinth many storeys high./o:p