It’s an untypical spring day in Los Angeles in 1990. The sliding glass doors that connect the hotel room to the swimming pool are open because, of course, it’s hot. But outside it’s raining. Monsooning, actually.

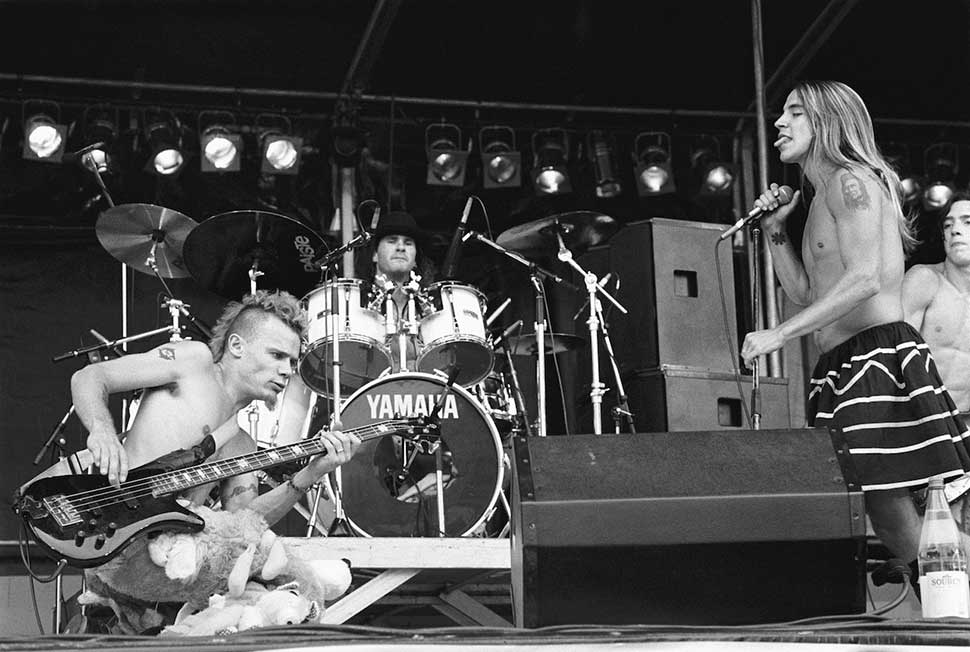

Into this unpromising vista bounds another rather untypical sight: Red Hot Chili Peppers singer Anthony Kiedis. He’s not famous yet, though reasonably well known, certainly in LA circles. He arrives alone, his long hair bedraggled by the rain, wearing a too-tight tee and what used to be called gor-blimey trousers – legs cut off below the knee, not yet a look the world is overly familiar with. What passes as his ‘outfit’ is completed by a pair of ancient grey trainers, and thin white socks stretched over his bony shins. The sight of him makes me laugh out loud. He looks so out of tune with what’s going on in the American rock world, which at this moment mostly means Guns N’ Roses and Metallica.

But that’s exactly what I like about the Red Hot Chili Peppers in 1990: their very otherness. At a time when hair-metal still rules and the concept of ‘grunge’ barely exists outside of a few clued-up hipsters in the Pacific Northwest, the Chili Peppers’ latest album, Mother’s Milk, is an anomaly: an illicit confection of funk, punk, rock and downright rudeness that defies the listener to even try to define it.

So when Kiedis looks me in the eye and without blushing describes the Chili Peppers as “the psychedelic sex-funk band from heaven”, I believe him. Whether that will ever be enough to expel the band out of their nice-but-niche comfort zone is another matter. When you’re that far out – and Mother’s Milk is the most far-out album to make a blip on rock’s notoriously rule-bound radar in many a year – it’s almost impossible to see a way back in.

At the same time, here we are at the start of a brand new decade and suddenly it feels like anything is possible. “We’ve done four albums now,” Kiedis says, “yet we still feel like the new dicks on the block.”

I offer him lunch and he orders a yolk-free omelette. Yolk-free? “I’ve got a new girlfriend. She’s 18 and demands rigorous sexual activity several times a day. Basically, you just can’t afford to have an ounce of fat, because a sexual diet is for performance. But it’s also for aesthetics.”

He could be describing his music, I say.

“Correct. But then music and sex is a lot the same to me. In fact I get the two mixed up all the time. In fact I like to get them mixed up. Good for the body, good for the mind.”

I sit back and allow myself a laugh. If only all bands were like this, I think idly, little knowing how many will soon try to be.

Twenty-five years after its release, Mother’s Milk is seen as the Chili Peppers’ game-changer, the starting point for their transformation from funky LA musical faddists to globe-straddling innovators and harbingers of a huge cultural upheavel. At the time, it was the last album they wished to make. Had Kiedis and bassist/co-founder Flea had their way they would have continued along the path laid out by their previous release, 1987’s The Uplift Mofo Party Plan, the funk-punk-rap-brat concoction that ended up being the only album to feature Kiedis, Flea and original guitarist and drummer Hillel Slovak and Jack Irons.

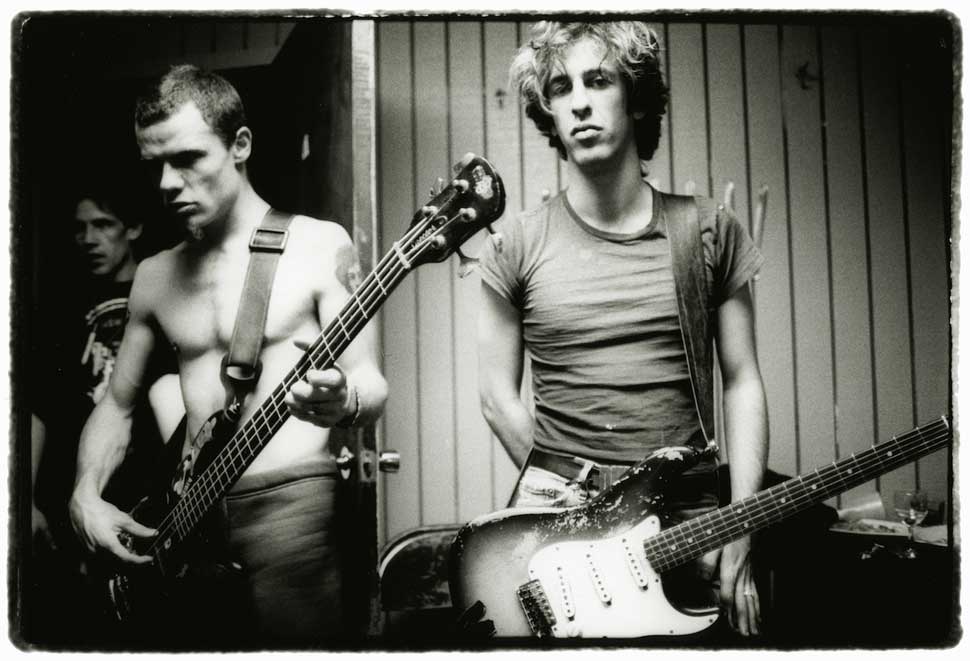

All four had known each other since attending Fairfax High School in West Hollywood, a hotbed of future musicians, actors and sport stars. But the Chili Peppers had always been the ‘joke band’. The ‘real’ band was What Is This?, who also dealt in the kind of funk-punk-rock amalgam, minus the fun and plus a frontman, Alain Johannes, who could actually sing rather than get by on sheer force of personality alone.

Push came to shove when both bands were offered near-simultaneous record deals. It forced a schism which found Kiedis and Flea sticking with the joke, while Slovak and Irons got really serious. By 1985, Slovak had bailed to rejoin the Chilis, just in time to record their second album, Freaky Styley. A year later, Irons did the same. The resultant album, The Uplift Mofo Party Plan, proved the joke could be killing, and that only clowns take themselves too seriously. TUMPP wasn’t a huge hit, but it was the first truly coherent RHCP album and remains a diamond in the dirt to this day.

But behind the scenes the band was falling apart. Though their whole mien had always spoken volumes for the added ‘creative consciousness’ of weed and psychedelics, both Kiedis and Slovak were physically and mentally dependent on heroin. While their profile was rising, the Chili Peppers themselves were in a steep downward spiral there seemed little chance of them successfully pulling out of.

At one point during the Uplift sessions, Kiedis was even fired from the band. But he eventually cleaned up long enough to complete the album – and help write the first truly breakthrough moment of their career: Behind The Sun, the sort of spangly, transcendent pop-rock moment that would later define their success.

- The A-Z of Red Hot Chili Peppers

- The Top 10 Best Red Hot Chili Peppers Videos

- Jane's Addiction: "The first alternative band to break - not Nirvana"

- Squids In: are Jellyfish the great lost band of the 90s?

Slovak found no such salvation. When he was found dead of a heroin overdose in June 1988, the joke had finally become sick enough to put them all off. Irons, already inclined to depression, was so devastated that he allowed himself to be admitted to hospital for psychiatric care. Kiedis, who had relapsed into his heroin habit, now went into emotional free-fall and vanished to Mexico for five weeks. When he returned to LA he checked himself into rehab for 30 days, the start of a period of sobriety that would stand him in good stead – at least for a couple of years.

“Like me, Hillel had the disease of drug addiction,” Kiedis told me in 1990. “He didn’t die of an overdose; he died from a disease. But in a strange way we found strength from that. It forced me to make a choice: I could either join Hillel, or I could try and finish my life.”

Kiedis managed to do the latter when he and Flea finally found what they were looking for in the shape of 18-year-old John Frusciante, a gifted, Hollyweird guitar player and Chili Peppers fan who would become a virtual Kiedis mini-me. He was joined by a big, burly 26-year-old drum killer from Michigan named Chadwick Gaylord Smith – just Chad, if you wanted to keep that smile on your face.

The band had originally reconvened in September 1988 for a short tour with George Clinton’s guitarist DeWayne ‘Blackbyrd’ McKnight and former Dead Kennedys drummer DH Peligro. They lasted just four gigs before McKnight was ousted in favour of Frusciante, who Kiedis “stole” from the clutches of fellow musical travellers Thelonious Monster. Shortly afterwards, Peligro was replaced by Smith.

“I wasn’t a big Chili Peppers fan,” Smith says today, “but I knew of the band – ‘Oh yeah, the guys with the socks on their dicks’ [a reference to the Chilis’ sometime on-stage apparel, immortalised on the cover of 1988’s Abbey Road EP]. I was more like, ‘Wow, a band with a record deal. Yeah, I’ll try out for that!’”

A veteran of several small-time local bands, Smith had relocated to LA just two months before. Unlike Frusciante, who he recalls “trying to be a Chili Pepper, or what he thought a Chili Pepper guitar played should be”, the drummer walked into the audition “bringing my own thing”. As a kid who had cut his teeth on Led Zeppelin and Deep Purple, that meant an immensely powerful yet head-batteringly percussive sound that literally made the room shake. “I remember Anthony saying that it sounded like Roman candles were going off inside the room,” recalls Smith. “I remember seeing him just laughing hysterically. I was like, ‘Does he think this is a joke?’”

In fact, as he later told me, Kiedis was suddenly aware that he was witnessing nothing less than the rebirth of his band. Two songs, both covers, cracked it for him: Jimi Hendrix’s Fire and Stevie Wonder’s Higher Ground. “I’m just thinking, man, this is fucking cool,” Kiedis said. “I don’t know what it is but it’s pretty fucking great.”

There was some debate over whether their new drummer might be “too rock” for them. “Like, ‘e’s got long hair and a bandana. He looks like he came off Sunset Strip,’” says Smith. Fortunately, musicianship and chemistry trumped snobbery, and Smith was offered the gig. Work commenced on writing their new album immediately.

“We were straight in, five days a week, writing. Right away we’d just kind of jam and take parts and put things together and find out stuff that sounds good, and Anthony would come up with some melodies or scats or something over the parts. And we came up with some things that we do to this day.”

If Mother’s Milk was a personal do-or-die for Kiedis and Flea, then it was no less important for their label, EMI America. After three albums that had sold poorly-to-modestly, and with their contract allowing for just one more, the Chilis’ entire career hinged on their fourth release.

Producer Michael Beinhorn certainly understood the urgency of the situation. He’d steered – or perhaps laboured through – the sessions for The Uplift Mofo Party Plan at a time when Kiedis’s smack habit was at its worst, and he was determined to make the most of their newly sober circumstances. More pertinently, the label had made it clear to Beinhorn that the Chili Peppers were drinking in the last-chance saloon. Put simply: the album had to be a hit.

Beinhorn worked the band hard at LA’s Ocean Studios through the summer months of 1989. The sessions were frequently tense. With capital-‘R’ rock still the biggest-selling genre for white, album-oriented acts, Beinhorn opted to steer the band away from the kind of in-joke ambience of their yappy funk-rap musical personas and into a more broadly appealing area where the sheer melodic punch of the new line-up became much more of a feature. This was most notable on their version of Higher Ground, the soul-funk classic they’d played during Smith’s audition. In the studio their jagged-edged version was revved up to the point of Guns N’ Roses-like ferocity.

This wasn’t something that sat well with Kiedis. He and Beinhorn clashed with increasing frequency, but the producer stood firm. “He was just trying everything he could to make it work, I think,” Smith says now.

In contrast to the singer, Flea welcomed the producer’s strong lead. The bassist had been forced to do the heavy lifting on the last album every time Kiedis disappeared for days into another smack-induced rabbit hole. Similarly, Frusciante revelled in the attention Beinhorn showered on him – the producer saw the hotshot guitarist as a way of bringing the Chili Peppers into the mainstream.

Up to then, the Chilis had relied on loose jams and bass-driven grooves as the foundation for their songs. Now, with ‘Greenie’ – as they dubbed Frusciante – on board, their new material became more structured, more melodic, more focused. More like songs, basically.

Mother’s Milk still contained its share of old-school Chili Peppers undulations, such as Good Time Boys and Subway To Venus, but the extra musical nous brought by Frusciante and Smith elevated things to another label. When they rocked now, they were a match even for GN’R – who they parodied at the end of Punk Rock Classic with a deliberately detuned burst of the Sweet Child O’ Mine riff (“We loved Appetite,” says Smith, surprisingly. “I remember sitting in the car, smoking weed, listening to that record with John. Anthony tried to explain that to Axl but I think it fell on deaf ears”). And when they laid down the funk on tracks like Sexy Mexican Maid, they no longer sounded like white-boy imitators, they sounded closer to the real deal. And when they combined the two, as on Nobody Weird Like Me, they took off into the stratosphere to a place that only they could call home.

Crucially, it was the songs that were harder to categorise that pointed the way to the Chilis’ stellar future. Knock Me Down stripped their sound down to its basic elements then rebuilt it so it sounded like nothing they’d done before. No less impressive was the furious Johnny Kick A Hole In The Sky, with its flaming, head-rush guitar and Kiedis’s first truly no-holds-barred vocal. There was even room for something as delicate and moving as Pretty Little Ditty, an instrumental oasis of calm amid the storm-born energy that surrounded it, worked up one cloudless LA day by Flea on bass and trumpet and Frusciante on guitar-shaped heart strings.

Of course, this being the Chili Peppers there were other, more earthy influences too. “For inspiration we would be watching porno films,” says Smith. “We even thanked porn stars on the sleeve. I have to reiterate that this was half a lifetime ago. We were really in a different place, emotionally and spiritually, of course. But that’s who we were. We were knuckleheads, man. That’s the shit that we used to do.”

Six months after the album was released, I asked Kiedis if he saw the Chilis as more of a rock band now. “Absolutely not,” he shot back. “We are a funk band. We don’t have anything to do with those other bands.”

To Kiedis’s undoubted chagrin, Mother’s Milk attracted some of the same people who had helped both Guns N’ Roses and Mötley Crüe bag No.1 albums that same year. When it was all over, the Chili Peppers had made an album that would not only give them their first serious taste of chart success – US sales of more than 500,000 – but also one that would signpost their own future.

Success, recognition, notoriety, money… none of it was instantly forthcoming. It took the release of the second single from the album, their riotous punk-funk version of Higher Ground – and the all-important MTV-rotated video that went with it – to truly get the ball rolling.

It was the beginning of the Chilis’ long-awaited career upswing. Smith puts their success down to chemistry – and not the kind that killed Hillel Slovak and nearly finished off Anthony Kiedis too.

“We got four guys in the universe that ended up being in Los Angeles at the same time, and really that was the whole thing of it,” says the drummer. “And being free and able to just be yourself. That’s really an important part of being in the Red Hot Chili Peppers.”

Or, as the ever carnally minded Kiedis said in that hotel room in 1990 while sheltering from the rain, Mother’s Milk was the sound of a band on the verge of full penetration.

“It’s very much like the process of making love to somebody: you start off with the foreplay – you kiss them and you suck their neck and you titillate their sensory areas with your fingertips, with the first couple of records. Maybe you start giving them head with the third record. Then you finally slip it in for the fourth. That’s essentially what we’ve done with our career up to this point.”

To extend Kiedis’s libidinous metaphor, it would be 1991’s Rick Rubin-produced, Blood Sugar Sex Magik that brought the world to orgasm. But with Mother’s Milk the Red Hot Chili Peppers were well on their way towards that climax.

This piece originally appeared in Classic Rock #197