Lemmy named his band Bastard before he decided on Motörhead. Lars Ulrich thought Thunderfuck was the way to go, before taking the name of his friend’s fanzine titled Metallica. And as Joyce ‘Baby Jean’ Kennedy recalls, the greatest of all funk rock bands once considered calling themselves The Motherfuckers.

“We wanted to say that,” she says, laughing, “but we couldn’t have gotten away with it. So we just took the ‘MF’ and became Mother’s Finest.”

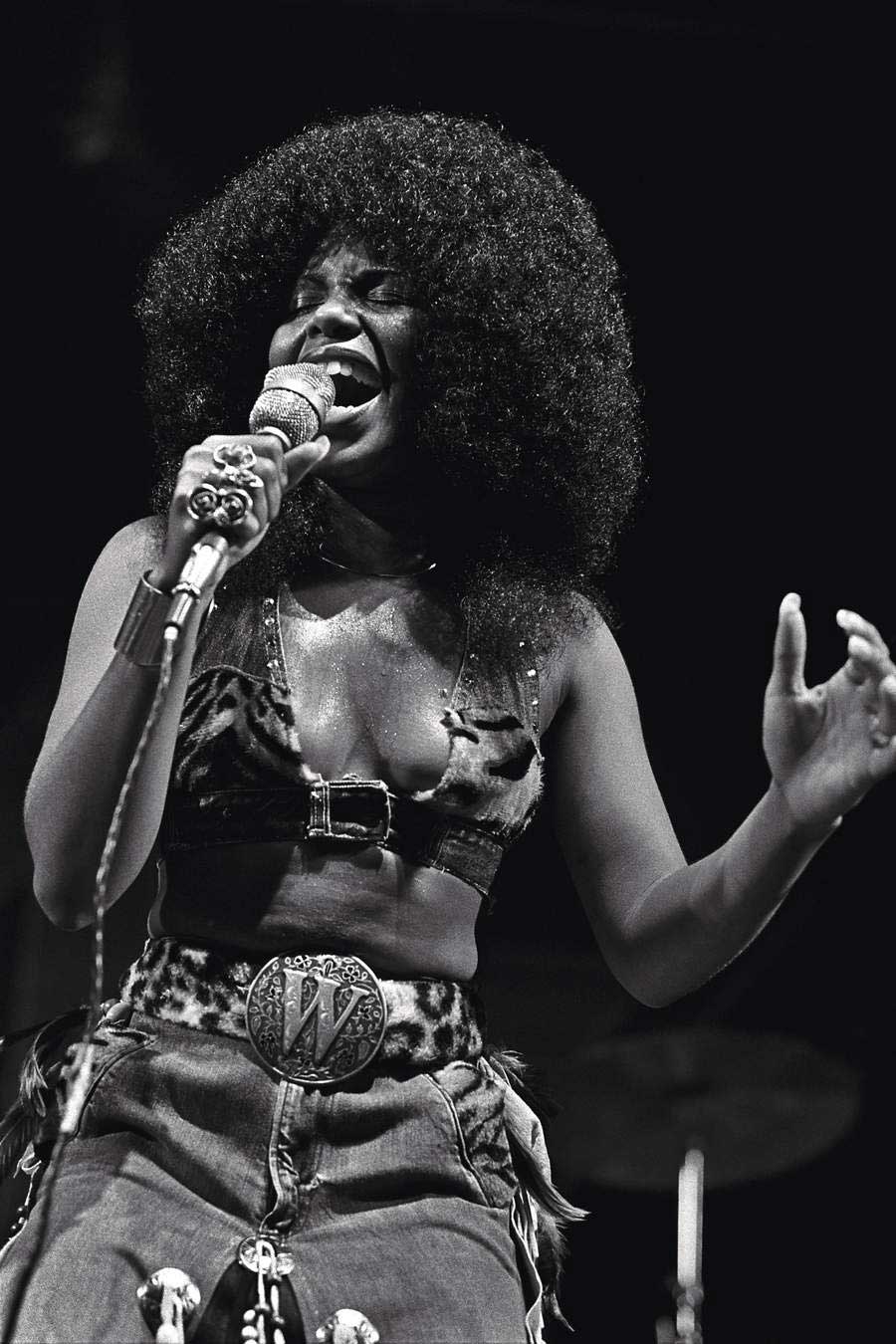

With a multi-racial line-up and a sound described as ‘Sly And The Family Stone-meets-Led Zeppelin’ – a combustible mix of soul power and hard-rock muscle – Mother’s Finest emerged in the early 70s as a band on a mission. As Kennedy puts it: “We wanted to make music that anybody could enjoy. We wanted to entertain and to be provocative, to give people food for thought. It was soulful, spiritual rock’n’roll, sexy and heavy with guitar. We were encompassing all of those things.”

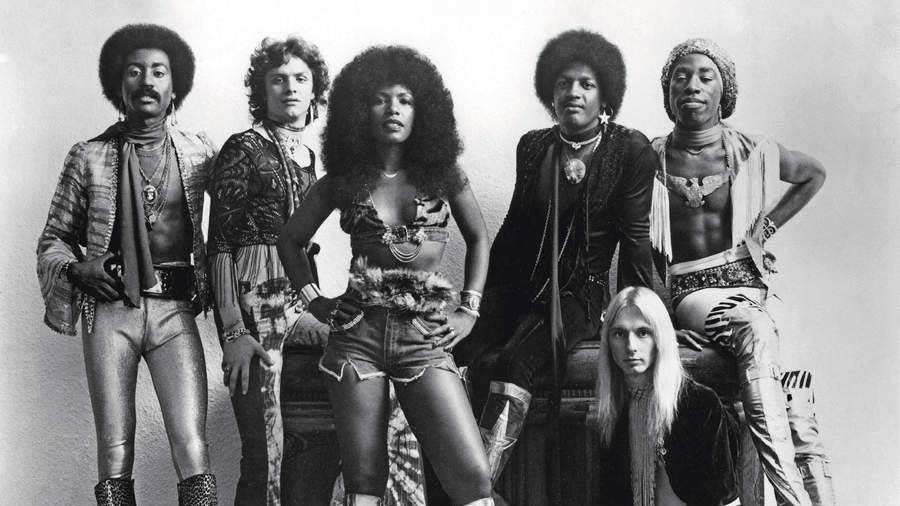

There were multi-racial groups and black rock stars before them – Sly And The Family Stone and Jimi Hendrix being the most significant. But “our band was predominately black”, Kennedy says. In the definitive Mother’s Finest line-up, fronted by Kennedy and her husband Glenn ‘Doc’ Murdock, and featuring Jerry ‘Wyzard’ Seay on bass and Mike Keck on keyboards, the white members were drummer Barry ‘B.B. Queen’ Borden and guitarist Gary Moore, whose nickname ‘Moses Mo’, would distinguish him from the Irish guitar hero.

It was with this line-up that the band made their reputation as a fearsome live act, and reached a creative peak between ’76 and ’77 with two albums produced by Tom Werman, who was then working with Ted Nugent and Cheap Trick, and would later make hit records for Mötley Crüe, Twisted Sister, Poison and others.

But for Mother’s Finest the big breakthrough never came. Which, Kennedy says, was a mystery to Werman. “Tom always wondered why this was one band he produced where it never happened on a huge level.” She says that from the band’s perspective, with a mixture of pride and fatalism: “We had all the things that would make it work, but for some reason the spheres didn’t see it that way.”

As she looks back on the glory days of a band she still leads, alongside Doc and Moses Mo – a band whose influence has carried over the decades in the music of Prince, Living Colour, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Lenny Kravitz, Dan Reed Network and more – she accepts that what made Mother’s Finest unique was also what made them a hard sell in what was a less enlightened era.

“The band was multi-racial, and that was rare,” she says. “Especially doing rock music with two people of colour out front. It was a beautiful thing. But back then nobody really knew how to make it work within the bureaucracy of the music industry. I just think that this band was a little bit before its time.”

The story of Mother’s Finest begins with two young people falling in love in 1965. Joyce Kennedy, born in the small town of Anguilla, Mississippi, had lived in Chicago since the age of seven. In her early teens she started out as a jazz singer, modelling herself on what she calls “big-voiced women” such as Aretha Franklin and Sarah Vaughan. Motown and other soul music also had a big influence on her.

“I liked strong singers like James Brown,” she says. “All those sweet, gentle, feminine voices, that was never my thing.”

In 1963, aged 16, she released her first single, I Still Love You, which became a regional hit. Two years later she was performing in a Chicago club when she met local boy Glenn Murdock.

“He was singing with a group like The Temptations,” she recalls. “I was eighteen years old with a hundred years of soul. It was one of those kismet things. We were attracted to each other right away, and we’ve been together ever since.”

By the time the 1960s were ending, with the rock era and the counterculture in full swing hey realised they needed to move with the times. They were working as singers for jazz star Woody Herman, and as Kennedy explains: “Doc and I were eager to change the course of what we were doing. He was in tuxedos and I was in long gowns. It was time to change and get into bell bottoms and that whole ‘peace and love’ attitude.”

During a tour with Herman, they discovered a kindred spirit in the man they would come to know as Moses Mo.

“We saw this blues band playing in a club in Dayton, Ohio,” Kennedy remembers. “And here was this long-haired cute little white boy on guitar. We hit it off, and when we were heading to Miami for another gig, Mo said: ‘Take me with you!’”

The three of them ended up stranded in Miami when the tour was cut short, but Kennedy says “this turned out to be a blessing”. A friend gave them a place to stay in the city, where they remained for the best part of a year. It was there that they hooked up with bassist Wyzard and the first of several drummers who came into their orbit, Doug Thompson. By early 1970, Mother’s Finest were in business.

“That was when the rocking started,” Kennedy says. “We just lit into it. Everybody we loved, we tried to grab a little bit from, whether it was the Rolling Stones, the Four Tops, Joe Cocker or Led Zeppelin. And it was because we were a cover band in the beginning that we derived our sound. Rock bands usually relied mostly on guitar and drums, but for us the bass was another power point.

"Doc and Wyzard and I had a natural three-part gospel kind of harmony that most bands did not have. So that became our signature. And we had a real smart guitar player. Mo loved funk bands like the Ohio Players, so even as we were evolving to a heavier rock sound, he was always in the pocket. He could do a lead guitar within the groove, and that made it funky.”

On a musical level, something special was happening. And on a personal level, Kennedy had no issue with being the only girl in a boys’ club.

“I was just as much a bad girl as they were bad boys,” she laughs. “And of course they were bad boys. It was the seventies!”

With spirits riding high, the failure of the band’s debut album came as a rude awakening. Titled simply Mother’s Finest, and released on RCA Records in 1972, it was over-produced, with strings and horns added to several tracks without the band’s consent. The album bombed. And although a follow-up was recorded, it was buried when RCA dropped the band.

It was a bitter pill to swallow. Having relocated to a new environment – Atlanta, Georgia – Mother’s Finest dug in, building a big following on the club circuit. And one night in 1975, their luck changed. Tom Werman, staff producer for Epic Records, was in Atlanta working on Ted Nugent’s debut album, and when he saw Mother’s Finest play live, he was instantly converted. “He became a champion for us,” says Kennedy.

The band signed to Epic, and their Werman-produced second album, also titled Mother’s Finest, released in ’76, was an emphatic, definitive statement. In heavy, funky songs such as Fire and My Baby, Kennedy belted it out like Chaka Khan and Tina Turner, while Doc Murdock delivered a defiant message in what inevitably became a controversial number: Niggizz Can’t Sang Rock & Roll.

“Doc is a Chicago brother. He knows that world better than anybody,” Kennedy explains. “And what he was saying with that song was the truth. He’s courageous like that. The whole idea was: blacks don’t do rock’n’roll any more, even though they started it, so we’re gonna do it – right here, in your face! We had a lot of people coming after us, because it was too early to say that word on record. But now you hear it every five minutes. Timing is everything.”

In 1977, with their next album, Another Mother Further, they continued to kick ass and push buttons. Doc flipped the bird to racial stereotyping in what would become one of the band’s bestknown songs, Piece Of The Rock: ‘Now go on and play your disco music/I got to rock’n’roll myself all night long…’

In another song they turned the tables on Led Zeppelin. Micky’s Monkey was essentially a cover of a 60s hit (originally titled with an ‘e’ in Mickey) by The Miracles. But the Mother’s Finest version was beefed up by Moses Mo playing the riff from the Zeppelin track Custard Pie.

“We put a soul lyric and melody on top of a rock classic,” Kennedy says. As for the provenance of said rock classic, which Zeppelin based on the song Drop Down Mama by American bluesman ‘Sleepy’ John Estes, she comments dryly: “People don’t always study history. But really, does that matter?”

During this period, Mother’s Finest performed in arenas as the opening act for funk titans Parliament and The Commodores, and some of the biggest rock acts of the time, including The Who, Aerosmith and Boston. “We hardly ever walked away without an audience going crazy about the band,” Kennedy says.

There was one exception: when they opened for Black Sabbath at the Philadelphia Spectrum in ’76.

“The stage was in darkness when we started,” she recalls. “We were killing it until the lights came on. But when that audience saw the band, it was all over. They flat-lined on us. They were totally not gonna to give us anything of their soul. Nothing. That was the only time that ever happened to us.”

She also recalls a similar reaction from a DJ at a rock radio station in New York City: “There was no picture of the band on the cover of Another Mother Further, and this DJ was playing the crap out of it. But then he saw a photo, he saw people of colour, and he pulled the record off the radio right there.”

There was stronger support for Mother’s Finest in Atlanta and around the southern states. “They played us on rock radio and black radio.” But that one hit record they needed never came, and eventually momentum was lost.

Under pressure from Epic to make an album with a stronger R&B focus, the band dialled down the rock’n’roll on 1978’s Mother Factor. The album hung around the pop charts for 20 weeks, but no hit single materialised. And although the band gained a cult following from touring in Europe, their dream of breaking big in America was gone.

In 1981 they returned to their classic sound with Iron Age, the heaviest album of their career. But after two more years and one more album, Mother’s Finest broke up – ironically, just as Michael Jackson was reaching a rock audience with the Eddie Van Halen-assisted Beat It, and Prince was about to drop his mega-hit Purple Rain. As Kennedy reiterates: “Timing really is everything.”

Four decades on, after a number of shortlived reunions, various personnel changes and another five studio albums (the most recent of which, Goody 2 Shoes & The Filthy Beasts, was released in 2015), Mother’s Finest recently competed a nine-week European tour, with Kennedy and Doc leading a six-piece line-up powered by Moses Mo.

“All the shows were sold out,” she says proudly. “We’re older, but we’re still out there kicking our legs up – literally!”

Kennedy recently released her solo EP Rock’n My Soul, but says there are no plans for another Mother’s Finest album. But then her voice rises. “I’m excited about the future, and I would love to play in the UK again sometime.”

Whatever the future brings, Joyce Kennedy is sure of what she and her band achieved.

“We were trailblazers without knowing that we were,” she says. “That’s it right there. We were paving the way for things to happen in music, but we didn’t know it. Looking back now, we were necessary. Nobody said we were gonna reach the level of the Rolling Stones or Aerosmith, but we did our thing and we gained our recognition in God’s own way.”

Joyce Kennedy’s EP Rock’n My Soul is out now via all streaming platforms.