Motörhead’s place in the rock pantheon is assured, and it can all be traced back to a creative hot streak that began with their second album, 1979’s mighty Overkill. In 2009, late, great frontman Lemmy looked back how three unhinged speed freaks made a stone cold classic.

Motörhead were formed by bassist/vocalist Lemmy in 1975, after he’d been kicked out of Hawkwind for allegedly doing the wrong type of drugs. So, he brought in drummer Lucas Fox and ex-Pink Fairies guitarist Larry Wallis to realise his vision of playing the planet’s dirtiest rock’n’roll.

A deal with United Artists led to the recording of an album in 1975. But the label was so unimpressed with the results that they shelved the record, only releasing it in 1979 as On Parole.

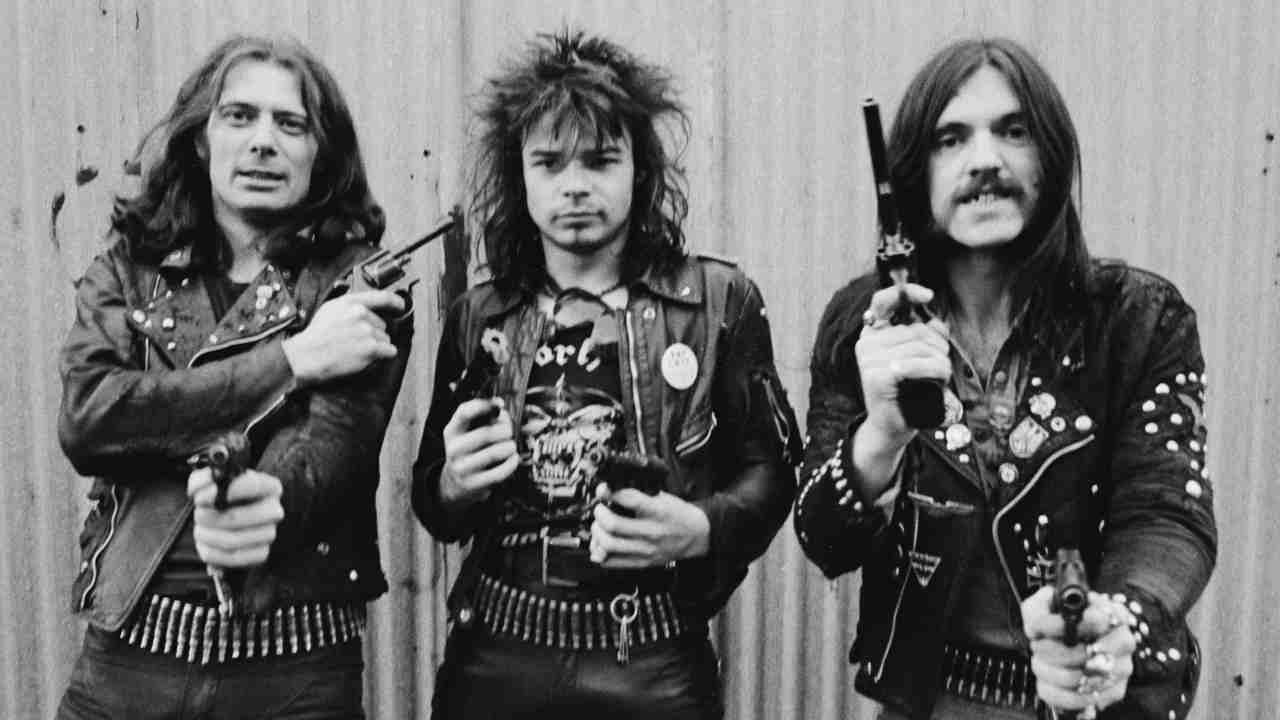

By this time, Lucas and Larry had been replaced by Phil ‘Philthy Animal’ Taylor and ‘Fast’ Eddie Clarke respectively. But such was the lack of interest in Motörhead, the band were ready to quit, until Chiswick Records offered them three days’ studio time to do a farewell single. Amazingly, the trio made an entire album in that time, and the subsequent self-titled release did well enough to suggest there was a future for the band.

“Bronze Records then got in touch via our manager at the time, Doug Smith, and offered us the chance to do a single,” recalls Lemmy. “So we went into Wessex Studios (London) with producer Neil Richmond and did a cover of the classic song Louie Louie. It did OK in the charts [making it to number 68], so the label gave us the go ahead to make an album.”

This would be the first time that the band actually had the opportunity to do a proper studio record.

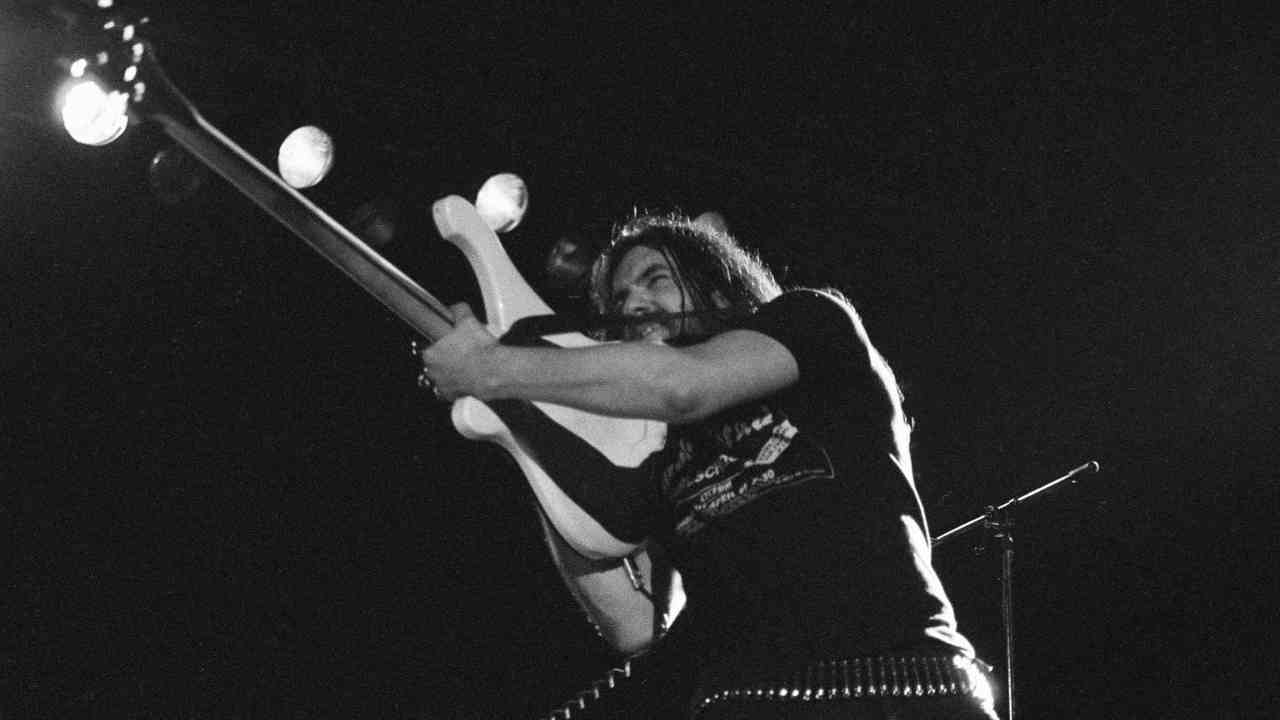

“Realistically, the Motörhead album was no more than a live recording. It represented what we were doing onstage at the time. But now we could actually stretch ourselves and see where it all led.”

The band decided to work with producer Jimmy Miller on the album. An inspired choice? Well, up to a point.

“It’s a long time ago now, but if memory serves me, we were given a list of four producers from which to choose – and the only guy on that list I’d ever heard of was Jimmy Miller, because he’d previously worked with the Rolling Stones. So that was the guy we went for.”

Jimmy was a recovering drug addict, and his problems with heroin in particular would come back to haunt the band when they subsequently renewed their working relationship for the Bomber album. But on Overkill, he was focused and positive.

“I know that Jimmy was never strung out for this project. He was happy and always smiling, and made a massive contribution. For a start, Jimmy knew his way round a studio, and as a band we certainly didn’t. He also became the fourth member of Motörhead for the time he worked on the album. It was a case of us being all in it together. We had to pull in the same direction to make it work – and Jimmy played his part to the full. It’s such a shame what happened to him…” (Miller died in 1994 at the age of 52 from liver failure, brought on through years of substance abuse).

Motörhead spent a six-week period from December 1978 to January 1979 in two studios, these being Roundhouse (where much of the recording was done) and Sound Development, both in London.

“We probably did about a six-week stint,” says Lemmy. “I suppose when you consider that we’d done the whole of the previous record in three days that’s a massive period of time. But what you also have to bear in mind is that this wasn’t a block of time in which we just concentrated on the album. We were also doing gigs. That’s the way things happened back then – it was far less regimented. However, we were all aware that studios cost a fuck load of money, so we weren’t about to waste our time.”

It was also an advantage that much of the material for the record had already been tested on the road; they’d been playing some of the songs for a while.

“Yeah, that helped to develop them. You’d be amazed the way songs change when you take them out on stage, so I suppose what we’d done – although not deliberately – was allow them to mature in a way that could never happen in the studio. But that’s an ongoing process. If you listen to the way we did Metropolis, for instance, on the record, it barely has any connection with what we now do live.”

Metropolis itself stands apart from the rest of Overkill, because it was written in haste, as the band tried to fill up space on the record.

“To be honest, we were one song short. So I had to come up with something literally overnight, I remember going to a cinema in Portobello Road (West London) that night; they were screening the classic Metropolis silent film from the 1920s, which was directed by Fritz Lange. That gave me the creative boost I needed. So, I went home, wrote the song, took it into the studio and we did it on the spot.

“One thing I do remember is that the guitar solo you hear on the song was the first take Eddie did – and he never even knew he was being recorded. Eddie was just tuning up when the tapes started to roll. And then he said, ‘OK, I’m ready to do the solo.’ We just replied, ‘Too late, we’ve already got it down!’ So, in a way what you hear on the album is just Eddie rehearsing and getting himself prepared. But, for us, he could never beat what he’d done first time. That’s what I mean about studios – you learn very fast what works and what doesn’t. We were all playing off each other.”

The other interesting track here, from a production viewpoint is Tear Ya Down – what appears on Overkill is the original version done with Neil Richmond for the B-side of the Louie Louie single. So, why didn’t the band re-cut this with Jimmy?

“I could make up some rubbish about vibe and attitude, and how we could never match what had already been done,” laughs Lemmy. “The truth is that we couldn’t be fucking bothered. It just seemed like too much hard work to go back and re-do the song just for the sake of it. So, we decided to leave it well alone.”

All of the tracks on the record were written by the band, apart Damage Case, where Mick Farren – former frontman of the 60s provocateurs the Deviants and an old friend of Lemmy - helped out on the lyrics.

“Mick wrote all of the lyrics at first, but then I improved on some of them, so what you hear is a collaboration between the pair of us, even though we never wrote them together.”

All of which brings us to the title of the album itself. To most people, this must have been something discussed by the band, and then unanimously decided upon. Wrong. The man who elected to call the album Overkill was…

“Gerry Bron, who owned Bronze Records,” says Lemmy. “I have no clue why he wanted to go with this as the album title, but he put the idea into our minds. Maybe he heard something in the song itself, and that was a track that I’d named. I recall coming in with the idea for the song and just saying to everyone, ‘Right get your ears around this, you sons of bitches’. But Gerry gave us the title for the album.”

All of this might suggest there was a certain chaos about the whole Overkill process. However, things were a little more disciplined than might appear to be the case.

“Our working day in the studio began about two in the afternoon,” explains Lemmy. “And we’d work solidly through until about 10pm. Why did we knock off then? So, we could get to the pub for a drink or two. Remember, this was back in the days before pubs could stay open as long as they wanted. They had to shut at 11pm.”

Overkill was released in March 1979, complete with a striking cover from artists Joe Petagno, the man who created the famed Motörhead logo. Yet he wasn’t satisfied with his work on the project.

“I had about a week-and-a-half to get it finished. But it was always a disappointment for me, personally. It should have been multi-layered. It was supposed to have a feeling that there was more to it – there were going to be more bits and pieces.”

Motörhead expanded their growing fanbase with this album. It reached number 24 in the UK charts, which, at the time, was a major breakthrough for the band. This was helped by the label’s cunning decision to release a green vinyl edition of the record just three weeks after it had first been issued in normal black vinyl, thereby ensuring that diehards would buy two copies. However, marketing tricks weren’t needed to convince people that Motörhead had come of age. If its eponymous predecessor had been hastily, spontaneously concocted, then Overkill showcased a band growing on every level. This wasn’t just a rabble trying to play louder than anyone else, but three fine musicians proud of their craft.

Overkill’s success opened a purple patch for the band, as they stormed through what many regard as their most creative period. Bomber, released later in 1979, reinforced their growing stature, while 1980’s Ace Of Spades brought mainstream acknowledgement. In 1981, the live No Sleep ’Til Hammersmith sealed their triumph, debuting at the top of the UK charts. But it also marked the end of an era. Iron Fist (1982) lacked the spark of previous releases and Fast Eddie quit soon after, angry over plans to record a version of Tammy Wynette’s Stand By Your Man with The Plasmatics’ Wendy O Williams (Lemmy eventually did this with Wendy as a single).

Motörhead remain one of the rock’s great bands, and much of their success can be traced back to Overkill – the album that put them on the right track after the false start of their debut. Today, it’s rightly regarded as a classic.

“Is it? I really don’t know!” says Lemmy, somewhat genuinely puzzled by the record’s undeniable stature. “What I hear is a record that’s… well, too slow! We play those songs much faster now. For us, it was a stepping stone, which led to Bomber – although I think Overkill’s a better record – and then on to Ace Of Spades. But what it did was prove we were a real band.”

Originally published in Metal Hammer 197, September 2009