Just like the rest of us, Lemmy finds it difficult to believe that this year Motörhead will have existed for a quarter of a century. “I thought we had three years in us if we were lucky,” booms the snaggle-toothed bassist/vocalist as we lounge about his Kensington hotel suite. “You don’t think chronologically at the start, you only realise how long you’ve been around at the end.”

To have endured a career this twisted, you simply had to come from a twisted background. Lemmy - born Ian Fraser Kilmister in Burslem, Stoke-on-Trent, on Christmas Eve, 1945 - fits the bill perfectly. The son of a RAF pastor, at the age of four, he had 10 teeth removed without anaesthetic and the young Kilmister quickly became aware that he preferred his own company to most other kids he knew. After his parents divorced, Lemmy pronounced his father to be “The most grovelling piece of scum on this earth, a weasel of a man with glasses and a bald spot.” When, in 1983, I asked him who his first crush was, he told me, “Champion The Wonderhorse.”

After a brief sojourn in Manchester in the mid-60s as the clean-cut guitarist in the Rockin’ Vickers, he relocated to London where he landed a gig as a roadie for Jimi Hendrix. He shared a flat with Noel Redding, forged an association with the London chapter of the Hell’s Angels, and remembers those days chiefly for the acid he regularly supplied to Jimi. “He’d send me out to score 10 trips. He’d take six, and I’d keep four.”

Motörhead - a title filched from a 1975 Hawkind single (which Lemmy sang) - were dragged kicking and screaming into the world the same year. Lemmy (a nickname he’d picked up because of his penchant for asking any and everyone: “Lemme a fiver”) had been sacked from the band after being detained at the Canadian/US border during a Hawkwind tour. The authorities had found a stash of white powder on him which they thought was cocaine (illegal in Canada) but which turned out to be amphetamine sulphate (bizarrely, still regarded then under Canadian law as a ‘pure food’). By the time he’d caught up with Hawkwind at the next gig in Toronto, however, he discovered he’d been “voted out of the band.” After four years with Hawkwind, during which he’d supplied the lead vocal to their one and only hit, Silver Machine, in 1972, Lemmy took his dismissal badly. Very badly.

“I’d sort of seen it coming, I just didn’t know when,” he shrugs now. “The only reason they bailed me out of jail, apparently, was because my replacement couldn’t get there on time. It’s a terrible thing to be fired, especially for an offence that everyone else was guilty of. So I came home and fucked all their old ladies,” he adds with all the detachment of somebody pouring a glass of milk.

What, every last one of ’em?

“Not the ugly ones, of course. But at least four,” he cackles gleefully. “Outrageous? No, not at all. I took great pleasure in it. Eat that, you bastards.”

The latest news, features and interviews direct to your inbox, from the global home of alternative music.

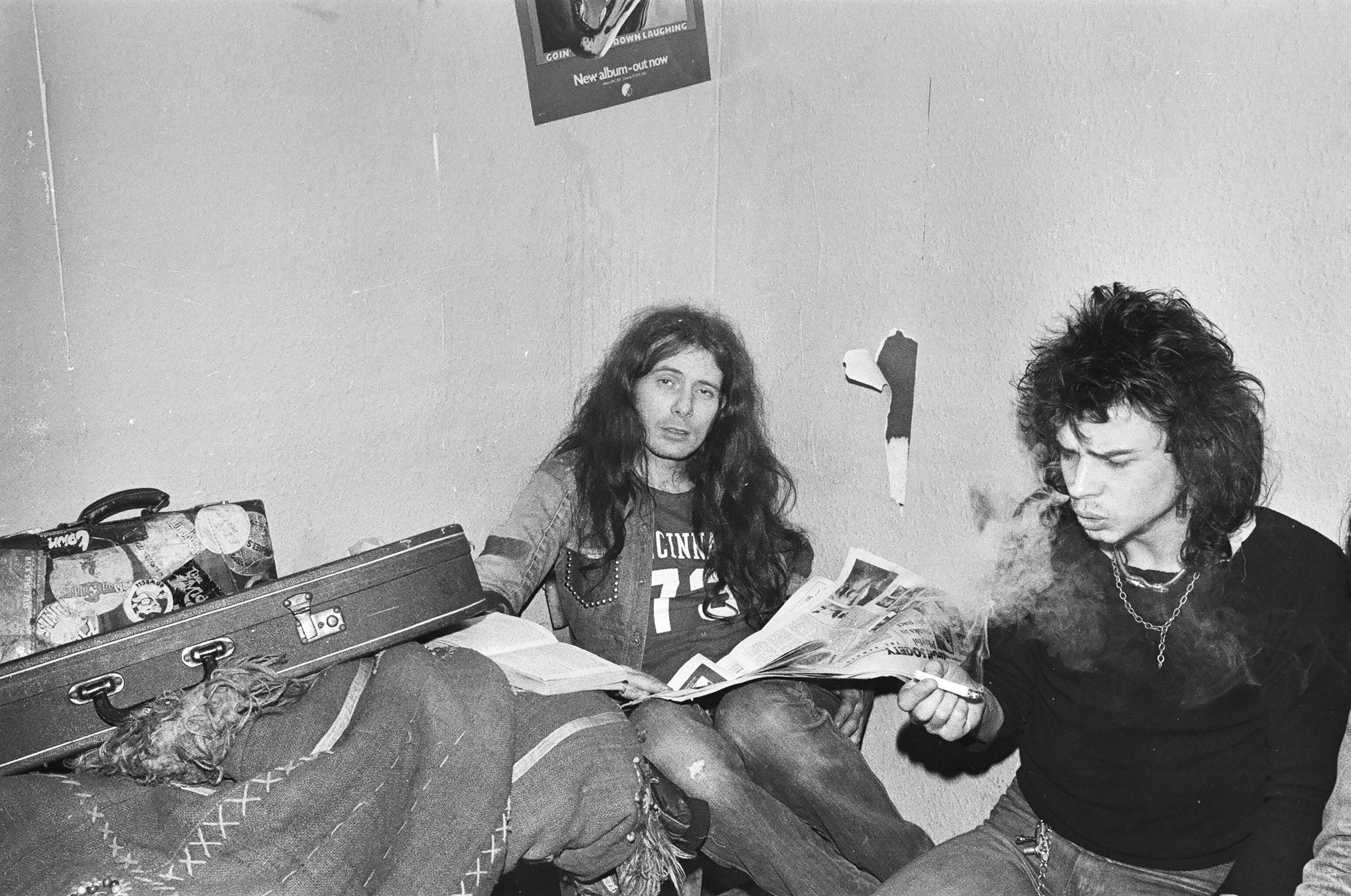

Lemmy’s earliest recollections of Motörhead, the band, involve: “Incredible poverty, living in squats. This bird we knew called Aeroplane Gaye used to work under a furniture store in Chelsea, and if anyone quit early we’d all dash down there and rehearse. We were that broke, but we did alright. We were struggling for a long time with no bread, then over about six months it just went whammo.”

The prototype Motörhead included former Pink Fairies guitarist/vocalist Larry Wallis and drummer Lucas Fox. Although they supported Greenslade at London’s Roundhouse in July, this line-up proved short-lived, and the latter was eventually replaced, in late ‘75, by Phil Taylor. “I met Lemmy through speed really,” Taylor later claimed. “Y’know, dealing and scoring. I wasn’t actually playing in a band at the time.”

‘Philthy Animal’, as he soon became known, was a former skinhead and Leeds United football hooligan, whose father had bought him a drum kit with the immortal words: “If you wanna beat something up, beat this up.”

The band’s first manager, Doug Smith, claims to have named the band Motörhead himself. An assertion that Lemmy disputes. What everybody agrees on, however, is that originally Lemmy had wanted to call the group Bastard.

“The name Motörhead was much better, the best name of any hard rock act in the world,” says Smith. “I don’t remember exactly which one of us said to call it Motörhead, but I was the one who had to agree to it, so therefore it was my idea,” Lemmy now reasons.

Nevertheless, Smith claims to have issued a press release announcing the band’s name while, as he so delicately puts it, “Lemmy was still sitting around on his backside and waiting for Hawkwind to invite him to re-join.”

“Why would he send out a press release about a new band if he thought there was a chance I’d go back to Hawkwind? That’s obviously garbage,” Lemmy insists.

Maybe he thought you needed a kick up the arse?

“Yeah, right. A kick up the arse from Doug Smith? Don’t make me laugh. He dropped us six months later anyway, we were with [former Moody Blues manager] Tony Secunda for two years.”

After Motörhead had cut their debut On Parole album for United Artists, the company rejected it (the album remained in the vaults until the band finally hit the charts with Bomber). The following March, Taylor found himself among of a group of blokes trying to earn a few extra quid by painting a houseboat in Battersea. One of them was part-time TV repair man and former Curtis Knight/Blue Goose guitarist ‘Fast’ Eddie Clarke, who was interested to learn that Taylor’s group were considering adding a rhythm player.

“So we organised an audition and jammed all afternoon, and Lemmy and I found we had a lot of things like the Yardbirds in common,” recalls Clarke now. “But Larry didn’t show up till the end, and when he did he wasn’t in very good humour.

“I didn’t hear anything for ages and assumed Larry didn’t want me in the band, then one Saturday afternoon there was a knock on the door and Lemmy was standing there. He gave me this fucking bullet belt and leather jacket and said, ‘You’re in’. Larry had gone and I had my uniform!”

During the legal melée that followed the On Parole album, they cut a single, White Line Fever b/w Leavin’ Here, for Stiff Records, and once again suffered the indignity of being shelved.

“The Stiff thing was the real pisser, because our single was sidelined while they put out things like Planet Airlines - a real obvious hit,” says Lemmy sarcastically, trying none too hard to conceal his bitterness. “But I’m used to not being appreciated by the business. The business has demonstrated year in, year out that it knows nothing about rock’n’roll. It’s not even interested in finding out. I didn’t join the business, I joined the band, and although it won’t admit it, I’ve beaten it hand over fist every time. They always do whatever I tell them not to, and they always fuck up.”

Nevertheless, these were shaky beginnings for the band.

“Was I always convinced of the band’s value?” Lemmy muses. “Well, maybe not during that little era with Lucas, but after we got Eddie and Phil in I knew we had something special. That was an excellent band from day one. I’d only written three songs for Hawkwind and I wasn’t too good at it yet. But this band has always been the eternal underdog, and we’re good at it.”

“It wasn’t until after three or four auditions that I realised we didn’t sound normal,” says Clarke. “There was Lemmy playing his bass as a rhythm guitar, and Phil and I were struggling to find out what we should be doing. For the first year, everyone thought we were fucking mad like U2 or someone, because it hadn’t quite gelled.

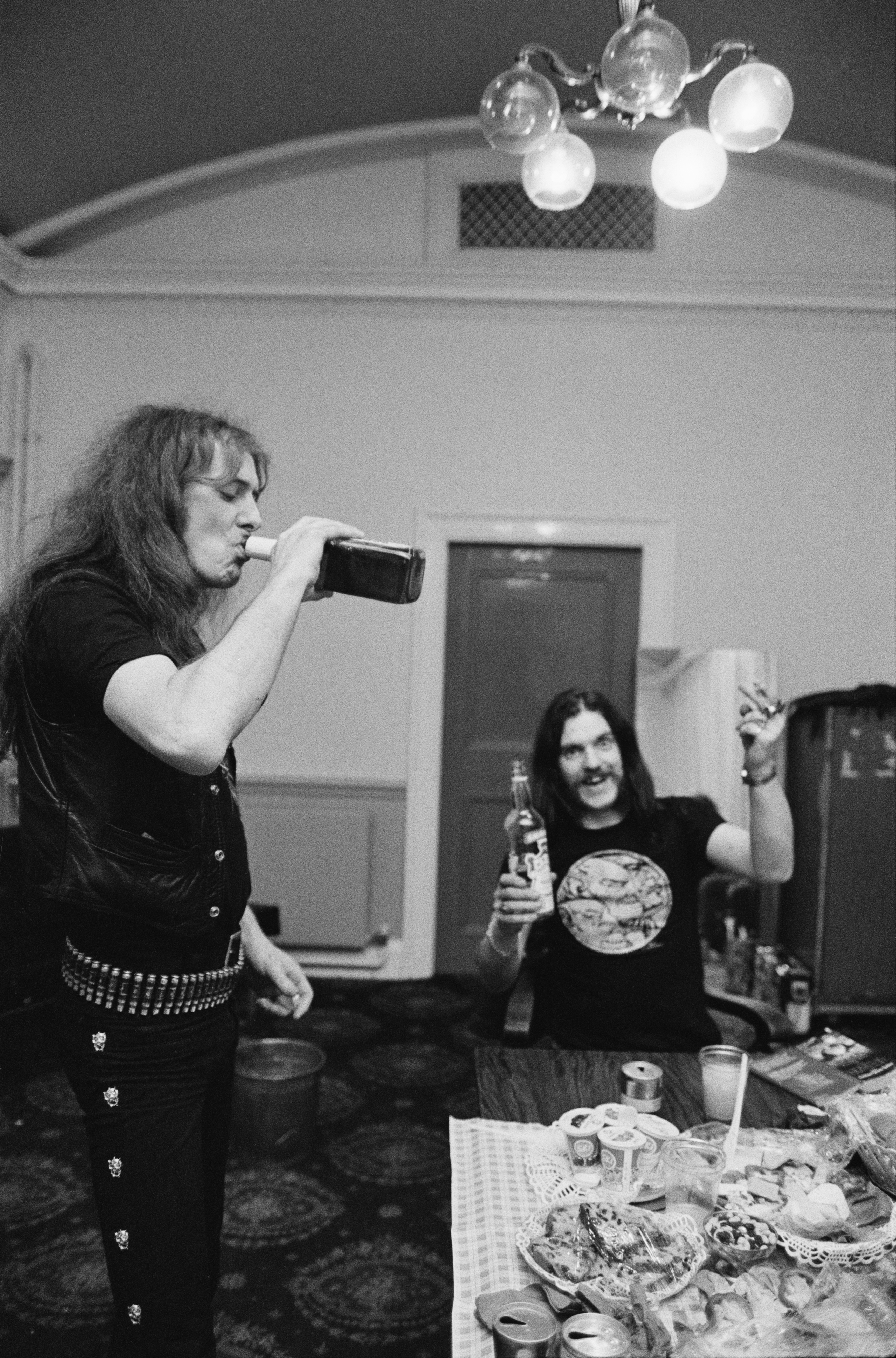

“Obviously, drink and speed were important in shaping the band,” continues Eddie, who was a moderate drinker until he joined Motörhead. “I was a dopehead. Speed was something that they all did, and I soon found myself doing it as well. Then I realised that having a drink with the speed mellowed you out and gave you an opportunity for a bit of kip. That was how my drinking career got underway.”

Motörhead’s break came in typically freak-ish fashion when Gerry Bron, the boss of Bronze Records (then home of Uriah Heep and Manfred Mann’s Earth Band), agreed, as a favour to a booking agent friend, to issue what actually became the first ever Motörhead single: their cover of cult 60s classic, Louie Louie. The band was by then actually signed to Chiswick Records, who had refused to release it.

Recalls Bron: “[Agent] Neil Warnock had said, ‘I’ve got a 12-date tour lined up for this band called Motörhead. But the promoter says that unless we get a single out to promote it, he’s gonna pull the plug’.”

Although Bron confesses he thought Louie Louie was “about the worst record I’d ever heard”, he released it “purely as a favour to Neil. And to my amazement, it went into the Top 75. I said, hang on a minute, this is a terrible record, but it’s gone into the chart without any kind of push at all, so I went to see them at Hammersmith Odeon and it was packed to the rafters with people going absolutely crazy. We had to sign them right away.”

Bronze Records had told the band that if Louie Louie went Top 75, they could secure them a place on Top Of The Pops. Sure enough, the band recorded their slot for the show on the Wednesday, and Clarke, who was “doing a painting job” on the following night, “had to ask the punters if we could watch their telly, because I was on in a minute! I was standing there in my overalls with a paintbrust in my hand…”

The success of Louie… (and its more representative B-side Tear Ya Down) was the start of a love-hate relationship that would benefit both band and label, yet culminate in trench warfare.

“We always seemed to have a problem with Motörhead,” Bron recalls with a sigh. “Nobody liked them, not on a professional level. They had a fantastic following, but licensees around the world absolutely hated them. We had a terrible job getting them to work with the band.”

“Yeah, Gerry Bron signed us as a favour, but he went on to release five of our albums, so that’s one helluva favour,” says Lemmy defiantly. “So, again, fuck you!”

The relationship between band and label became so fractious that Lemmy would often tell concert audiences to go out and steal the group’s latest recording, “Because we don’t get the fucking royalties anyway.”

Nevertheless, as a consequence of Motörhead’s success, Bronze also signed Girlschool, the all-girl combo who Lemmy and co. had taken out on tour as their support act in 1978. The two bands later recorded a covers EP under the name of Headgirl. As a result, the two groups developed a strong bond, and over the years Lemmy dated both guitarist Kelly Johnson and bassist Gil Weston.

“I even lived with Gil for quite a while,” he says now. “When I got her the Girlschool job I said it would break us up, and sure enough it happened six months later. She married the tour chef!”

Early on, as a gesture of solidarity, Motörhead decided to split the profits equally three ways, even though Lemmy was writing the lyrics and Eddie the majority of the riffs. “We knew if we did make it that we didn’t want Lemmy and I coming to work in Rolls Royces and Phil on a pushbike,” says Clarke. As the guitarist now insists, the reason for the band’s early success was their very togetherness. Although there was tension, their bond was seemingly unbreakable.

“You hear a lot of good things and a lot of bad things about Lemmy, and most of them are true,” said Taylor at the time. “He is a cunt, he is a bastard, he does knock other people’s chicks off. But he’s also incredibly funny. Every time you go out with him it’s a memorable experience.”

“We had a bond, and it went beyond whether you liked someone or not,” adds Clarke now. “Me and Phil were especially close because Lemmy was a bit of a loner. I can’t image being any closer to anyone else than those two, and it never even entered my mind whether I even liked Lemmy or not, because it wasn’t even an issue. We felt almost indestructible because we’d had so much shit thrown at us and we’d decided that no matter what happened, we were gonna fuckin’ carry on.

“The music business created Motörhead because they tried so hard to scupper us, and it made us dogged. What happened years later, when I kinda got out of the band, was they started to wonder whether they liked me or not. Then you’re doomed. Being in a band’s like being in a war, you don’t give a fuck whether or not a guy’s feet smell, you wanna know if he’ll keep you alive.”

Their now infamous hedonism even began to reach the dailies when the Daily Mirror reported that a suitably refreshed Taylor had broken his neck after falling down a flight of stairs in a Belfast hotel. Thankfully, only vertebrae were fractured. Were there ever any concerns that somebody might actually die of the lifestyle, though?

Clarke: “Not for a fucking minute. We were too busy partying. There were times when I got the red mist and let off a bit of steam, or Phil would smash up the odd hotel room and break his hand, but that was all part of it. The fights between me and Phil were legendary, we’d really try to hurt each other.”

Doug Smith: “I was worried about the band many times. I once thought Phil Taylor was dead of an overdose in New York. And in America the police arrive whenever you call an ambulance, so I’d been going around his room hiding every drug I could find, hoping they’d think he’d just collapsed. It was life-threatening all the time, for all of them - even Lemmy, who I once thought was gonna have a heart-attack when we got to a gig in Canada and there was no speed around.”

Motörhead’s manipulation of the press was masterful. Playing heavily on their hard-living, biker image, their notoriety was well-earned. Mick Wall, then a humble Sounds scribe, travelled to an early gig in St Albans, and reported: “I never really recovered from the coach trip. 60 minutes speeding from Chalk Farm Road is all it took. Not nearly enough time for readjustment to a state of mind equipped to deal with the onslaught of Barbie dolls thrust suddenly into your company, the fresh chunks of meat hanging from butchers hooks over each table, or the pints of artificial blood, shot through syringes no doubt, over the seats and windows. Not enough time to do anything except sit on your hands and gape at [publicist] Motorcycle Irene and her chums swanning around pouring drinks.”

In late ‘79, Motörhead made London’s Evening News for “clocking in a staggering 119 decibels at a recent concert”. An unrepentant “band leader Lemmie” (sic) retorted: “The kids may be injuring themselves, but how could we stop them from pressing their heads against the speakers? They keep on shouting to turn it up.” The Daily Mirror then joined in, declaring: “Their music is so loud it’s like your brains being forced down your nose.” And a couple of years later, a picture of Lemmy cuddling the then 16-year-old Coleen Nolan appeared in The Sun as part of a story that seemed to suggest their was something dubious going on. In fact, Lemmy was participating on the Don’t Do That single with the Nolan Sisters and the Young And Moody Band.

The release of the Overkill and Bomber albums both came in 1979, but they’d had plenty of time in which to perfect their sound. The latter crashed into the charts at No.12, causing Sounds to describe it as “music to perform lobomoties to.” To promote it, they had already sold-out two nights at London’s prestigious Hammersmith Odeon.

In July 1980, the band played a show that crowned their early achievements. The Heavy Metal Barndance at Stafford Bingley Hall also featured Saxon, Girlschool, Angel Witch, Mythra, Vardis and White Spirit, and was rightly hailed as a success. But even then, the strain between the protagonists was beginning to show.

“Lemmy had been up for three days drinking vodka and fucking chicks,” Clarke explained years later. “We’ve got 12,000 kids crammed in and waiting for us. All day people have been offering me lines of coke and everything, and I’ve had one fucking Heineken because I want to be together for this show. 55 minutes into the set, Lemmy disappears backwards and collapses. Afterwards, me and Phil are furious, going: ‘You let us down’. And he was saying, ‘Me being up for three nights had nothing to do with it’. The fact that he was up for three days getting blow-jobs had nothing to do with the fact that he’d collapsed onstage? No, of course not!”

Although 1980’s Ace Of Spades entered the chart at No.4, Clarke remembers it as “becoming a little more difficult. There was pressure because we were famous.” Yet Lemmy’s prime recollections are that the band were, “Ready to kill.” His main memory is of “Eddie lying on his back, helpless with laughter and feeding back on the solo for (We Are) The Roadcrew,” which he’d written in five minutes flat.

Again, Soundswent overboard, their correspondent Garry Bushell awarding …Spades the full five stars and insisting: “Motörhead are heavy metal in the only meaningful sense of the term. Everyone else is just pretending.”

Around that time, the trio flew to America for their first US shows, including their debut at the Orange Bowl in Miami supporting - of all bands - Heart. Afterwards, at the headliners’ request, they hooked up with Ozzy Osbourne and proceeded to stun audiences.

“The Yanks were shocked, horrified,” Eddie recalls now. “When we finished they’d just stare at each other. It wasn’t until Chicago, probably two months into the tour, that we got our first encore.”

The band’s pinnacle came in 1981 when No Sleep ‘Til Hammersmith entered the UK album charts at No.1. The bassist was in New York at the time and remembers being asleep when he received the news, and although he claims to have told whoever had made the call to ring him back the next morning, he regarded the chart placing as a vindication. Clarke’s biggest regret was that with being on the other side of the Atlantic, nobody could buy them any celebratory drinks.

“The strangest thing though,” he says now, “was that it got an over the top review in Melody Maker, who were the people who’d called us the worst band in the world. I had to say to Phil, ‘Now suddenly we’re the definitive live band, they were calling us cunts last week’.”

Despite the fact that the album wasn’t even recorded in Hammersmith (it was actually done in Leeds and Newcastle), the strangest thing about No Sleep… was that the band hadn’t even wanted to release it in the first place.

“The great story behind that album is that [Bronze’s distributors] Polydor were very, very keen on it, especially somebody there whose name I now don’t recall,” Gerry Bron relates. “But this guy ? let’s call him Dave Smith, got a telex from Lemmy saying, ‘I hear you’re going to release the live album. Does Dave Smith like hospital food?’ The band were away in Australia at the time, so we put it out anyway and it went straight in at No.1 and, of course, Lemmy never said a word afterwards.”

“We sent Bronze the famous ‘six-foot fax’ with all the things we thought were wrong with it - it went on for pages because we thought the thing was terrible,” laughs Eddie. “The mixes had been done while we were away and we were fuming. Apparently he just threw it in the fucking bin [but] the album comes out and goes straight to No.1 so who’s gonna fuckin’ argue? We know nothing!”

“We knew that No Sleep… was gonna do well because people had been waiting for a live album from us for three years, but never in our wildest dreams did we think it would go straight in at No.1,” Lemmy confesses. “Actually, I was more pleased when Ace Of Spades went in at No.4, because No Sleep… was a one-off. That said, it was also our death-knell because you can never follow a live album that goes straight in at No.1. What are you gonna do, put out another one?”

Just before the band had departed for their second US tour to promote the then new Iron Fist album, a series of dawn raids on their homes had lead to the arrest of Philthy for possessing 2.2 grammes of cannabis. Back home, a warrant was issued for his arrest. Fortunately for Lemmy and Fast Eddie, they’d stayed out all night, but that didn’t stop them from claiming in Sounds that somebody was “out to stitch us up.”

While the band were away, police were also called to Lemmy’s gaff after his flatmate, actor Andrew Elsmore, was found stabbed six times in the head and chest with his body partly burned.

As Clarke now explains, things had started to become strained between himself and the other two. After the murder at Lemmy’s pad, Doug Smith had moved the group into a shared house in Clapham. While the tour continued, Clarke’s then girlfriend was the first to move their possessions in, also picking the best bedroom.

“I know it sounds incredibly petty, but it was the beginning of the end,” sighs Clarke now. “I was also seeing one of Lemmy’s ex-girlfriends, and even though I asked him if it was alright if I went out with her, he never got over it. Lemmy forgot the golden rule, he started to think about whether he liked me or not.”

The disappointing reaction to the, in truth rather patchy, Iron Fist album and tour made it clear that the magic wouldn’t last forever. Bronze had failed to get the album into the shops in time for the tour. Despite this, Philthy threatened to leave the band unless they played a huge chunk of the new material, and it fell on deaf ears.

“It killed the tour stone dead,” says Clarke. “It was our worst fucking tour, the kids didn’t come alive until the encore. I was devastated.”

“The ‘Iron Fist’ album was bad, inferior to anything else we’ve ever done,” agrees Lemmy now. “There are at least three songs on there that were completely unfinished. Having Eddie [Clarke] produce it was a mistake that even he would now probably admit to. But there you go, we were arrogant. When you’re successful that’s what you become, you think it’ll go on forever.”

“Listen,” says an indignant Clarke, “I swear on my mother’s grave, I didn’t want to produce Iron Fist! I’d produced the first Tank album [1982’s Filth Hounds Of Hades] and producers all wanted 10 or 20 grand - from a band that were on two hundred quid a week. Why should we pay some cunt that? I didn’t want to play and produce. But Doug Smith was forever telling us the band was skint, and Lemmy’s whole attitude was, ‘Let’s let fucking Fancy Bollocks do it, he’s just done the Tank album, he’s got the best room in the house, he’s nicked one of my birds and he’s a cunt’.”

After seven years of threatening to do so, Eddie Clarke finally quit the band in May ’82 after a blazing row in a New York hotel room over a version of Tammy Wynette’s ‘Stand By Your Man’ that Lemmy was cutting with the late Plasmatics singer Wendy O. Williams.

Almost 20 years later, the subject clearly still rankles with Clarke. “I still feel justified in saying that Wendy O. Williams thing was a piece of shit and that we shouldn’t have done it because Iron Fist hadn’t gone down well and the tour had been a disaster. We needed something with a bit of credibility, not another fucking joke. Lemmy even suggested crediting it to Motörhead and Wendy O. Williams with a disclaimer that it had nothing to do with Fast Eddie Clarke - well, that really fucking did me. It wasn’t about me, it was about Motör-fucking-head.”

With hindsight, though, Lemmy believes Clarke’s departure could have been avoided.

“Yeah, Eddie was just going through one of his crazes,” he says today. “He used to have ’em all the time. He had this craze on this guy Will Reid-Dick, who had co-produced the Iron Fist album with him, and he came over to New York to do that collaboration. Wendy, rest in peace, wasn’t the type of chick who got the song right away, she had to work at it. They [Clarke and Reid-Dick] got impatient and became very counter-productive, so I ended up producing it myself while they were outside the studio bitching. To leave a band after seven years just because of that was ludicrous. He’d left several times before, but Phil and I just couldn’t talk him back that time. Eddie was stupid that day.”

At the time, Lemmy told Sounds: “He could have left at a better time, before or after the tour, but two gigs in is a bit strong.”

Almost inevitably, Fast Eddie and Doug Smith remember things differently.

“We had this big row and had separate dressing rooms in New York because they didn’t want me anywhere near them, but afterwards I did go into their dressing room and said, ‘Listen guys, the gig was good and I’d like to do the rest of the tour if we can put this thing behind us’. But they said, ‘No way, man, fuck off’. That’s God’s truth. They say I left the band, and I did used to throw wobblers, but that’s not the way I saw it. It broke my heart because those were the greatest times of my life.”

“Eddie may well have offered to finish the tour, but Lemmy and Phil just weren’t interested,” explains Smith. “It had taken all my negotiating skills throughout the previous night to get them to play the New York show, at which they completely ostracised Eddie. For them, that was it.”

“The thing is, Motörhead never got recognition from other musicians, and I think that’s why the split happened,” says Eddie. “They loved Thin Lizzy and Brian Robertson and probably used that as an excuse to get me out of the band, at least in Phil’s mind. You know, get a proper musician in. I don’t mean that in a horrible way, but it’s something that Phil and I have discussed since. And let’s face it, Brian Robertson was not a good choice.”

Nevertheless, ‘Robbo’ was appointed and left soon afterwards, while Philthy came and went from the band over the following years, amid claims that he was no longer up to the task. Indeed, Lemmy once collared me in the foyer of the Marquee for a concert review I’d written in which I’d lambasted the band for not playing* Overkill*. “Philthy’s legs had gone,” he said simply.

After leaving Motörhead, Taylor played with Robertson and ex-Sensational Alex Harvey Band/Michael Schenker Group bassist Chris Glenn, yet soon returned to ask Lemmy for his job back.

“The terrible thing was, I agreed,” Lemmy sighs. “And I don’t think he ever forgave me for it, because he hadn’t liked asking. I didn’t like having to tell people we couldn’t do Overkill anymore because he couldn’t play it, because he really should have been able to. He wasn’t that old, just too out of it and apathetic, taking the wages.”

As he would be the first to admit, you can’t make people change their ways. “Not unless they want to. We warned him twice over a period of about 18 months, but he didn’t buck up. He lost it, didn’t care any more. You can’t make people care.”

Clarke, however, retains his loyalty to Taylor. “No disrespect to the drummers that followed him, because they’re all good players. But none of them have what Phil had,” he insists. “He was all over the fucking place, really involved in the song. If Lemmy would sing* ‘See ya later baby’*, Phil’d give it a little bit of extra just on that bit. Everyone since has just played straight through.”

Although Fast Eddie enjoyed brief post-’Head success with Fastway and released a solo album, It Ain’t Over Till It’s Over, in 1983 which featured Lemmy on one track, neither he nor Philthy are desperate for a return to the music business. Still in regular contact with Lemmy, Clarke has also been sober for the last 11 years since an incident when he started coughing up blood.

“I used to say I’d drink till I died, but as soon as the deep dark claret started coming out, I was on the phone to my doctor,” he laughs.

“So much for all my big talk. But there was nothing bigger in our lives than Motörhead. Phil and I have never recovered. We’ve never had families because Motörhead was our family.”

Which begs the final question: everyone else is doing it, will we ever see the ‘classic line-up’ back onstage together?

Clarke: “You’ll have to ask Lemmy. If he was up for it, maybe. I’ve always got loads of time for him. Maybe we’ll play together if this 25th anniversary gig comes off. I’ve heard lots of rumours, but I’ll believe it when I hear it from Lem.”

Last year, Dave Ling caught up with ‘Fast’ Eddie Clarke for Classic Rock #200 to talk about the passage (and ravages) of time. Below is the hitherto unpublished transcript.

So how old are you now, and how old do you feel?

I turn 64 in October, but I’m starting to feel quite old. I’ve had some trouble with my heart, some stents were put in. I’m on bloody pressure pills and I’ve got emphysema through smoking. They’ve discovered that I’ve got prostate problems as well, so I’m also on pills for that. When I walk down the road I rattle like a tin of Smarties.

You still sound surprisingly upbeat?

I am. Man, considering all that’s wrong with me I think I look pretty good. It’s just when your lungs get fucked, that messes with everything else.

At least you’re not drinking or smoking on top of everything?

Yeah. I quit the cigs in 2008, though I still have the odd reefer. The drinking stopped in 1989 because I didn’t feel the need to go back to it. I wasn’t a drinker before I joined Motörhead, but being in a band with Lemmy and Phil, after about 12 months of speed and no sleep, that’s when I discovered Special Brew. Within another 12 months I had a drink problem. But it was fun, I’m not complaining. It’s the price you pay. I talked to Lemmy when he came out of hospital and he told me, ‘I’m drinking water now, man’. When I asked why he replied, ‘My kidneys have gone’. He’s on heart pills and he’s got diabetes, when you get older these things creep up on you. Lem sounded positive, though, but you could tell he was miffed about it [getting older]. I’m sure that Ozzy feels the same. I saw him a year ago. Basically, he’s clean now but it does start to get a bit boring sometimes.

What are the best and worst aspects of growing older?

Well, nobody prepares you for the fact that you start to look ancient. Or that body parts begin to go wrong. Getting up the fucking stairs can be a problem. You look at young girls and think, ‘Fuck me, she’s gorgeous’ but you forget that you’re 60 years old and have to slap yourself and say, ‘You silly old cunt’. Old age is possibly the worst thing that can happen to anybody. All this fucking wisdom shit… yeah, there’s a bit of that. Things that were once important now seem quite trivial. But nobody prepares you for that; they can’t because it’s never going to happen to you. Luckily I’ve avoided arthritis, so I can still play. In fact, I’m playing some mean old guitar on this new record [Make My Day, Back To The Blues] though I ended up singing on it myself because Toby [Jepson] let me down.

On what basis?

Everybody [else] wanted to tour Eat Dog Eat [Fastway’s reunion album, 2011] but he was too busy getting Little Angels back together. I saw a few songs of theirs at Donington, what a joke. They’re a fucking pop band. Get a grip, mate. There’s men and boys.

You don’t want us to print that, of course.

No, fucking print it. He needs to be fucking told. That album was surprisingly popular; we could’ve toured the world. Had I known that [he wouldn’t be available] I wouldn’t have done it. Albums are expensive to make when done the old fashioned way in a studio. But things change as you get older… I’m actually friends with Doug Smith again now.

Motörhead’s former manager? Really?

Yeah. There was a lot of acrimony but at the end of the day it’s only fucking money. We see a lot of each other again now.

We all go to a lot more funerals now, though…

Don’t we just? I just buried my best friend 18 months ago. He’s the guy that saved me when I was bleeding from the mouth, took me to rehab. He died of fucking stomach cancer – died within five months [of diagnosis], like Paul Samson who almost went overnight [in 2002].

Look at Wilko [Johnson]… he shouldn’t be here, that’s amazing. But we’re in the twilight of our lives. I harp on about that on my album, ‘I’m getting too old for this game’. But I’m telling it like it is. Even if you pull a fucking bird, you’ve then got this gargantuan effort to make anything happen, dropping a load of pills and you’re pole vaulting around for a week.

Knowing what you know now, would you still have left Motörhead?

That’s the fucking thing, I didn’t leave. I did ‘kind of’ leave, but Phil [Taylor, drums] also ‘kind of’ left, too. They called my bluff when I refused to do the record with Wendy O Williams [of the Plasmatics, a cover of Stand By Your Man]. I wanted to carry on after that but they said, ‘No, man. It’s fucking over’. Can we talk about Phil [Taylor] briefly?

Sure, are you still in contact?

He came to stay with me about a year ago. Fucking hell, he’s had a brain haemorrhage. They saved his life but he’s not the same now. He’s still there, he still remembers stuff but he’s just a little bit slower than he was. For all of our differences I still love Phil to bits. The three of us… what we did together [in Motörhead] was so incredible. It’s a shame we can’t be together in our old age to have a fucking laugh about the good and bad times.

What have these twilight years taught you?

Well, I’ve wasted a lot of my life not playing. When I look back I think, ‘Fuck me, what was I doing in the 1990s?’ That’s why I’ve made this album. Obviously, nobody buys albums anymore but I did it for the crack, and I think I’ve got at least one more left in me. I know I’m not the best-liked man in the world; I tend to rub people up the wrong way. Maybe that’s why no one likes me, because I’m such a twat? I’m starting to realise that as I’m older. [Laughs]. It’s not my intention, it just happens that way – look at the reactions of those I’ve worked with, Phil [Taylor], Lemmy, Dave King [original Fastway singer] and now Toby Jepson.

But at least you can look back at it all in the knowledge that you were your own man?

Oh, fucking right. I was lucky, after Motörhead I fell on my feet with Fastway. Look at poor Pete [Way, co-founder of Fastway]. Despite being his own worst enemy he’s one of the best-liked men in the business, but this prostrate thing’s got hold of him… oh my God.

The way things are turning out, dying at 35 of a drug overdose might not have been so bad. We’re all going to go down this chute to* really *old age. Near where I live, in Twickenham, there’s a place that all of the old TV people go to stay [in their retirement]. It’s a home for actors. You see some very famous people hobbling about and you hardly recognise them. But it’s going to fucking happen to us all, no-one escapes.

Want more Motorhead? Click the link below to find out which Motorhead songs Orange Goblin’s Ben Ward thinks are their best work, and then disagree with him.

Dave Ling was a co-founder of Classic Rock magazine. His words have appeared in a variety of music publications, including RAW, Kerrang!, Metal Hammer, Prog, Rock Candy, Fireworks and Sounds. Dave’s life was shaped in 1974 through the purchase of a copy of Sweet’s album ‘Sweet Fanny Adams’, along with early gig experiences from Status Quo, Rush, Iron Maiden, AC/DC, Yes and Queen. As a lifelong season ticket holder of Crystal Palace FC, he is completely incapable of uttering the word ‘Br***ton’.