April 19, 1973. The plush listening room of AIR Studio is a world away from the bustle of Oxford Circus below. The atmosphere is muted with anticipation as Mott The Hoople gather for the first time to listen back to their recently completed sixth album.

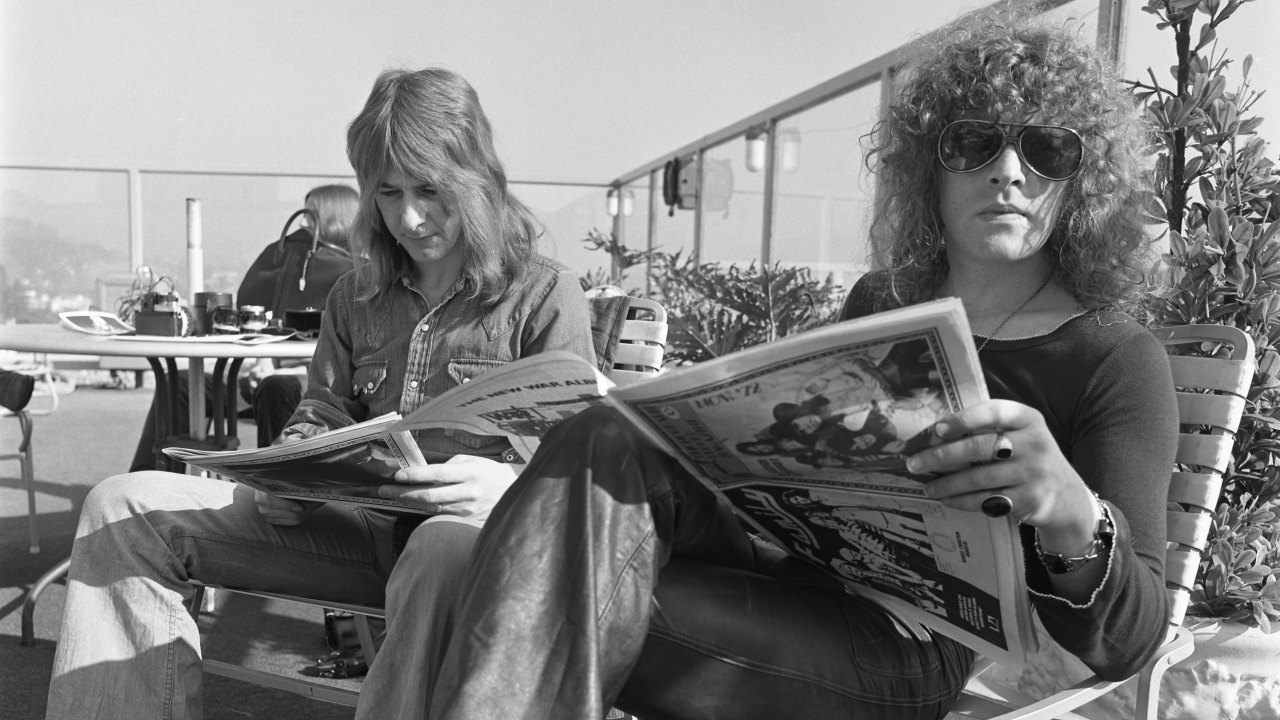

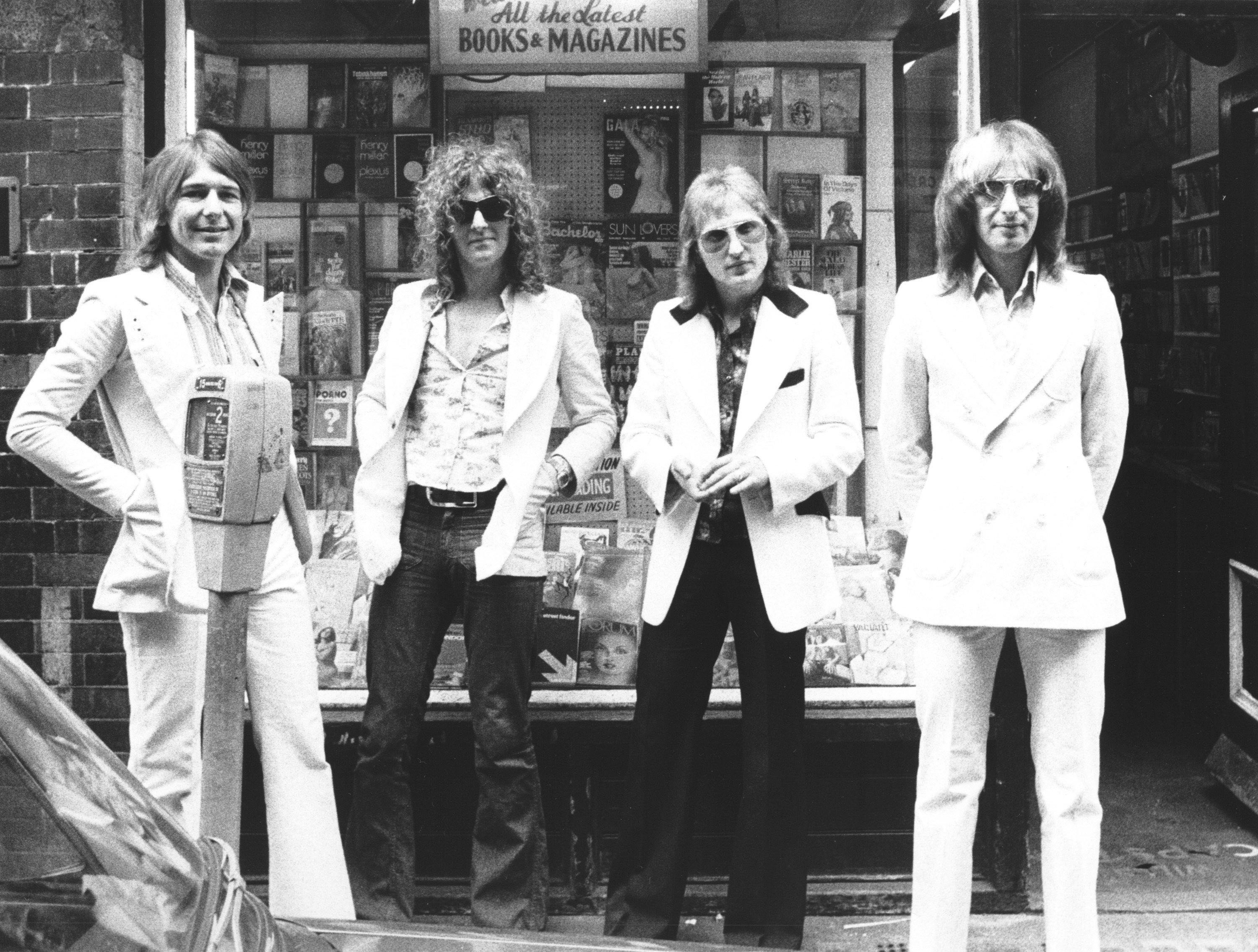

Drummer Dale ‘Buffin’ Griffin, bassist Pete Overend Watts and guitarist Mick Ralphs are all here, smiling nervously as they ready themselves for the big moment. Finally, Ian Hunter strides into the room, ever-present shades covering his eyes, and nods at his band-mates. Pleasantries are at a minimum as engineer Bill Price feeds thick master tape into the playback machine.

It’s a pivotal moment for Mott. With this record, the band have taken a gamble that may prove to be foolhardy, or even downright insane. Not only have they recently lost Hammond organ maestro Verden ‘Phally’ Allen, but also they’ve broken away from David Bowie, the man who saved their career the previous year, and opted to produce this new album themselves. And now it’s time to find out if their gamble has paid off.

I’m in the room for this momentous occasion due to my position as president of Mott The Hoople Sea Divers, the fan club I founded after nearly three years of following the band. The fan club members have been waiting with bated breath for this most monumental of albums, and I’m on hand to give them a world exclusive.

Despite what’s riding on it, the pre-playback wait carries an air of triumph. Pete tells me that the album will be called Mott, and that they’re shortening the group’s name accordingly. “We feel like a new band now,” he says.

They sound like one too, as the accelerating piano intro of opening track All The Way From Memphis fills the room. By the time Hunter gets to the song’s punch line, legs are pumping, knees are being slapped and everyone in the room is grinning with a mixture of happiness, relief and maybe a little disbelief. By the time of the second track on side two, Ballad Of Mott The Hoople (March 26, 1972 Zurich) – a song that poignantly reflects on the band’s split the previous year – this emotionally scrambled teenager is struggling to suppress some potentially embarrassing welling-up.

Mott know they’ve cracked it. They’ve produced the best album of their tumultuous career, finally realising the potential that producer Guy Stevens spotted in the summer of 1969 when he formed, named and nurtured them. They’d long been one of Britain’s best live bands, but their record sales had never lived up to their potential. This was the one that would change that.

Forty years on, Mott stands as one of the landmark albums of the 70s, with its combination of hot-wired rockers and wide-open, autobiographical ballads. Thanks to a combination of hard graft and sheer self-belief, and despite internal friction and pressure, Mott had reached the highest point of their roller-coaster career; 1973 would prove to be their golden year, even if it would fly off the rails within 18 months.

But all that was in the future. Back on that April afternoon, once the last sweet glimmer has faded from the huge speakers, the room is momentarily still before the quiet is broken by an eruption of whoops and celebratory hand-shaking. I ask Ian Hunter what he thinks, and he quietly offers the typically straightforward verdict he would favour in initial press reports: “It’s bleeding amazing”.

The first time Mott The Hoople’s name appeared in print was in mid-1969, in a copy of Zigzag, the UK’s first serious music monthly. Pete Frame, the man behind Zigzag and the band’s most vociferous early champion, reported how Guy Stevens had put together a new band made up of Hereford outfit Silence and struggling songwriter Ian Hunter. The producer saw the group as a collision of Stones-y rock’n’roll and Dylan-style balladry.

Stevens attempted to capture his vision on the band’s self-titled debut album, released in late 1969 on Island. But it was on stage where Mott truly came to life. At a time when dowdy greatcoats and 25-minute drum solos ruled, Mott cast back to rock’n’roll’s original untamed, seat-smashing spirit, their gritty rebel flash tempered by Hunter’s sensitive but tough confessionals.

This punk-presaging approach and down-to-earth humility grated with the press, but it attracted a fervent following that the band dubbed ‘the Mott lot’. This devoted gaggle mainly consisted of disenfranchised working-class kids (one of whom, a kid called Mick Jones, would go on to form The Clash). In July 1971 these fans made the news when Mott were banned from the Royal Albert Hall after being accused of starting a riot during a particularly lively gig to mark their second anniversary.

But while Mott provided an adolescent road map for a legion of teenagers, the band themselves were becoming increasingly frustrated that their albums – the debut, followed by 1970’s schizophrenic Mad Shadows, plus the country-flavoured Wildlife and the frayed, frenzied Brain Capers, both released in 1971 – hadn’t sold well.

“You were selling out the biggest venues in the land and you weren’t having any record success,” says Hunter. “That’s not going to work for long. You have to have the record success to go with it.”

Something had to give. And in March 1972 it did. Following an on-stage ruck during a grim gig in a disused Zurich gas station, Mott The Hoople decided to split. Little did they know that the decision would inadvertently set in motion the events that would eventually lead to Mott.

The band’s saviour would be David Bowie. The singer had already announced countdown on the launch of Ziggy Stardust, though he had yet to make the giant leap to true pop stardom – that would come a month later, with the release of the single Starman.

A huge fan of Brain Capers, Bowie heard of the band’s demise when Overend Watts asked him for a job. Horrified, he took it upon himself to persuade them to stay together by offering one of his songs, Suffragette City. When Mott turned it down for not being radio-friendly, Bowie hastily finished off another song he’d been writing and presented it to them: All The Young Dudes.

“He played it for us on an acoustic guitar at his manager’s office,” Hunter recalls. “I knew straight away it was a hit. Chills down my spine.”

Produced by Bowie, All The Young Dudes was released as a single in July, rising to No.3 and turning a rejuvenated Mott into hit-makers at last. But while its parent album, also titled All The Young Dudes, boasted its share of good songs, Bowie’s production neutered Mott’s power, especially set next to a record like the fearsome Brain Capers. The album stalled at No.21, but Mott were still chart stars for the first time in their lives.

Ever since Bowie approached them with …Dudes, he and his manager, Tony Defries, had been courting the band with a view to signing them to Defries’ MainMan company. At Bowie’s behest, Defries bought the band out of their Island Records contract and helped get them a deal with CBS. Mott soon found themselves part of the exotic MainMan circus, which included Lou Reed and Iggy Pop. “We were in that circle,” recalls Mick Ralphs. “There was a nice bunch of people involved in that whole set-up, bisexual, arty-farty, that we weren’t a party to before. It was interesting, different.”

It was during this period that I started their official fan club, Mott The Hoople Sea Divers, named after the final track on All The Young Dudes. Assisted by my then-girlfriend, Karoline, we started carrying the news about the band by writing irate letters to the music press.

My first Mott gig in my new presidential capacity was the opening night of the …Dudes tour on September 15, 1972 at Dunstable Civic Hall. The dressing room was buzzing with first-night preparations. Ian Hunter had squeezed into a skintight black leather catsuit made by the tailor who created Iggy Pop’s silver Raw Power strides, and was about to hang a huge, gold ‘H’ guitar around his neck. “Look at this,” he laughed, raising his arms like some superhero fetish god. Overend Watts stood seven-feet tall in winged, leopard-skin platforms, his tresses coloured platinum (achieved by using car spray paint). Phally Allen looked less comfortable, his sartorial extravagance stretching no further than a maroon velvet jacket.

The hall was packed with Ziggy-worshipping space cadets here to hear the hit single (and maybe catch a glimpse of Bowie). Ian was conscious that the diehard fans would be glowering that they’d lost Mott to the glam scene. “The old fans didn’t like it because we weren’t theirs any more,” he says. “We didn’t invent glam rock. It was there so we went for it. We knew that was what it was going to take at that time. We weren’t daft. We could see the funny side of it, but nevertheless we still did it.”

But the darkness was creeping back in. A show at London’s Rainbow Theatre in mid-October degenerated into a mess of pent-up rage, aimed at a cynical music press and exacerbated by equipment problems. The set climaxed with the band’s gear being trashed after a cacophonous You Really Got Me. “We deliberately blew it,” says Ian. “We turned the lot up and let them have it.”

By the time they played a half-hearted gig at the London College Of Printing later that month, Mott’s star had sunk lower. Dealing with MainMan wasn’t helping either. The band’s ‘ordinary blokes’ ethos was at odds with the cigar-chomping Defries’ ruthless vision.

A new song that had been added to the band’s set, Hymn For The Dudes, provided a window into Hunter’s mind. Lines such as ‘Go tell the superstars their hairs are turning grey’ illustrated how he felt it could all end at any moment. After years of scuffling, he wanted to grab any success that came his way while the going was good.

In New York, during an American tour in 1972, they met up with David Bowie, who played Ian a new song he’d written, the doo-wop-inspired Drive-In Saturday. For a few days it looked like being the next Mott single. Accounts differ as to why it wasn’t. One version was that the band rejected it as “too complicated”, another was that Bowie wanted to keep it for himself.

Either way, it turned out to be the right choice. To follow …Dudes with another Bowie song would have belittled Mott’s own song writing prowess, pushing them deeper under Bowie’s shadow and into MainMan’s pockets. As Ian Hunter said at the time: “We can’t live off David our whole lives, we’ve got to have our own song.”

Between the final show of the US tour in Memphis on December 22 and a one-off show at Friars in Aylesbury on February 10 the following year, Mott lost Verden ‘Phally’ Allen. Uncomfortable with glam, and pushing for the band to record more of his songs after getting Soft Ground on …Dudes, he quit the band impetuously.

“When David came along it cleaned everything up,” Phally says now. “We lost our edge with the live thing, and Ian took over. I just went: ‘I’m off!’. I never thought it through. I was driving down Oxford Street and there was a poster: ‘Mott Shock – Allen Quits!’. I thought, ‘Fucking hell, I’ve left the band! What have I done?’. But it was too late then.”

The show at Friars in February was a warm-up before a four-date mini-tour with the Sensational Alex Harvey Band supporting. I was at the gig, and while it was odd witnessing a four-piece Mott, their set included several promising new songs they’d been working up, including Drivin’ Sister, Hymn For The Dudes and Rose.

Allen wasn’t the only one on the way out. Mott were about to split with MainMan and Defries, though Bowie was still insisting that he’d produce the band’s next album.

“It worked with MainMan for about a year, then it stopped working,” says Hunter. “So Stan [Tippins, tour manager] rang Tony and said he’d had enough. Tony only had management of the …Dudes album. We had contracts with him but I kept ’em at home. We never signed them. Too sticky.”

And so it was that Mott found themselves stepping out of the shadow of David Bowie and escaping the MainMan machine. It may have given them a sense of freedom, but it also meant their next move would be more important. Everyone agreed that it was make-or-break time.

Ian Hunter set out Mott’s post-Bowie manifesto. “Mott are only into rock’n’roll because rock’n’roll is music,” he said. “Sure, it has its various trimmings. So now make-up is moving people’s arses. I don’t need that – just give me a spotlight.”

The game-plan was not just to capture Mott’s essence, but also to work out what that essence was. “We had to find a complete Mott The Hoople sound,” he said. “Like somewhere between the Stones and Dylan. But it had to be new. It had to sound like Mott The Hoople”.

Not that they were completely breaking with the past. It wasn’t lost on Hunter that on All The Young Dudes it was the soaring, defiant title track that stood out. He wanted every new track to stand shoulder to shoulder with that mini-masterpiece.

Being the oldest and most experienced member of the band, Hunter had naturally assumed the role of frontman, singer and main songwriter, although he had never tried to assert himself as leader. Post-Bowie, his rock’n’roll survival instincts also kicked in, though Mott was still run as a democracy.

“That was the problem,” he reflects. “I remember Bowie telling me: ‘You’ve got to take this over’. So I went back and said: ‘David reckons I should take over the band’. And Ralphs said: ‘Like fuck you are’. And that was the end of that. I think diplomacy had a lot to do with the band’s demise. For some reason it was always a major drama to get all the others to agree to something. All I want to do is write songs, play good music and, at that stage in the game, stay where we were, which was big.”

It was with that in mind that Mott began to look for producers for their next album. The wish-list included Roy Wood and Gary Glitter mastermind Mike Leander, but they were busy. Instead they began work with engineer Bill Price at AIR 2 studios in London.

The next single was top priority. Hunter had become the driving force behind the song writing process, to the extent that the band asked if he was making his solo album. Hunter counters this today. “Mick and I would be dicking about in rehearsal. If Pete and Buff said: ‘What’s that?’ then it would be picked up on.”

Which was how they wrote the single they needed, Honaloochie Boogie. Between them, Hunter and Ralphs came up with this rollicking song about the electrifying sensation of being converted to rock’n’roll. Pete and Buffin thought it was great. Ian wasn’t too sure: “It worked as a stopgap.”

Inspired by Roy Wood, who was recording See My Baby Jive at AIR, Mott decided they needed to bolster the song’s arrangement, and brought in Bowie/Bee Gees collaborator Paul Buckmaster to add electric cello, as well as saxophonist Andy Mackay, whose band Roxy Music were recording next door in AIR1. Mott’s confidence was given a boost when Mackay’s bandmate Brian Eno heard the track and declared: “What do you want a producer for? This sounds great!”.

“That was all we needed. So we carried on as we were, and that’s how Mott got done,” recalls Hunter. “But it was hard.”

The Mott album was recorded between February and April 1973. With their producers’ hats on, the band strove for a happy medium between Guy Stevens’ manic power and Bowie’s pop suss (Hunter credits the latter with showing them how to capture their sound and make a hit single). It helped that Hunter had finally found his magic song writing formula, best exemplified by the track that would eventually open the album.

All The Way From Memphis was a rousing road anthem that used the real-life saga of a lost guitar on Mott’s last US tour to illustrate his point that life in a band was far from glamorous: ‘You look like a star, but you’re still on the dole.’ Elsewhere, the line ‘You climb up the mountains and you fall down the holes’ was the perfect summation of Mott’s entire career.

The rest of the album was no less accomplished. Whizz Kid was a bittersweet bump’n’grind about a New York groupie, its haunting, national anthem-echoing chorus showing that Mott had assimilated some of Bowie’s slick production tricks. Saw-toothed petrol-head rocker Drivin’ Sister came complete with BBC sound effects, while Ralphs’ I’m A Cadillac/El Camino Dolo Roso displayed the dexterity he would later show in Bad Company.

There were also two songs for the fans: Ballad Of Mott The Hoople was the song that marked their temporary split; the other was the dramatic live favourite Hymn For The Dudes. The latter silenced the room during that first playback session at AIR, with Hunter’s reflections on the transience of stardom boosted by sweetly sepulchral organ and a soaring gospel chorale from backing singers the Thunderthighs (aka Karen Friedman, Dari Lalou and Casey Synge). ‘Go write your time,’ exhorted Hunter, ‘go sing it on the street.’

The final track on the album was originally set to be Rose, an intimate Hunter ballad about a doomed junkie, but it was replaced by the mandolin-adorned break-up lament I Wish I Was Your Mother, one of the great overlooked tracks of Mott’s career (Rose would end up on the B-side of the next single).

But this creative roll threw up its own problems. Mott knew they were out on a limb, and the burning desire to pull it off sparked some intense moments. The sessions were riddled with rows and stand-offs between the four members, each of them determined to have their say. It all manifested itself in one track, the aptly titled Violence. As the band turned the melody from Cat Stevens’ 60s hit Matthew And Son into a sinister, Shadows-style theme, Hunter cajoled and screamed over the top of them, his rantings gouged by Graham Preskett’s berserk violin. But while it found Mott playing out their psychotic frustration, it also laid bare the instability at the band’s heart. A drunken row involving guitarist Mick Ralphs would play its part in his departure just a few months later.

“Listening to Violence for three days drove us nuts,” recalls Hunter. “I think that was it. Mick thought it was more my input than his on that record. Which it was, and so there you go. And that was the end of the original Mott the Hoople, really.”

In 1973 the weekly music papers were the fans’ lifeblood. And for a diehard Mott fan it was hugely satisfying to see the front page of the May 5 issue of Sounds bellowing: ‘MOTT: ALBUM, SINGLE’. The paper was trumpeting the release of Honaloochie Boogie on May 25, followed by the album in July.

The fan club sold the album at less than the £2.48 which CBS insisted on charging to cover the cost of the cover (initial UK pressings boasted a gate-fold sleeve with an illustration based on a bust of a Roman Emperor, printed on transparent plastic).

We also sold the Honaloochie Boogie single, the immediate release of which was even more nerve-wracking than that of the album; what if it bombed? Thankfully, its concise pop innocence clicked with both public and radio, and it broke into the Top 20, climbing to No.12. A few weeks later I was invited to watch Mott record a Top Of The Pops appearance – a strange experience, watching the small crowd in the old BBC Television Centre studio being shunted around to make it look packed out. While Mott handled it all with polite professionalism, I was determined to appear in the broadcast and so sneaked behind the band when they were filming.

While Hunter still didn’t believe the album would be a hit, the unanimously positive reviews declared it their best yet. The album entered the chart at No.11 when it was released in July, and continued to rise over the following weeks.

Ironically, earlier the same month, on stage at Hammersmith Odeon, David Bowie had announced his ‘retirement’, closing the door on his initial phase – something which would have undoubtedly claimed Mott had they not broken away from him. Their gamble had paid off, the decision compounded when All The Way From Memphis followed the album into the Top 10 when it was put out as a single soon afterwards.

“Mott is in the charts and it’s an incredible feeling when you’ve all worked hard for a long time,” Hunter declared at the time. “It’s a great feeling.”

With Ballad Of Mott The Hoople touchingly dedicated “For All The Seadivers”, and the name and address of the fan club appearing on the sleeve, my duties went into overdrive. One day, my doorbell rang and I opened the door to find a smiling Asian girl and her mate standing there. She was studying at Lady Margaret Hall in nearby Oxford and, being a huge Mott fan and having written in several times as Member 262, she had decided to drop by and say hello. The girl’s name was Benazir Bhutto, and she would go on to become the Prime Minister of Pakistan, before being tragically assassinated in 2007.

With Mott in their pockets, the band were hurtling along at full pelt. But there was a bump in the road ahead. The most pressing concern was replacing Verden Allen for an upcoming US tour. The band recruited two keyboard players, Hammond organist Mick Bolton and pianist Morgan Fisher. The latter had been a member of 60s pop group the Love Affair, and his suave flamboyance and like-minded sense of humour made him a perfect fit for Mott. The first thing Fisher recorded with the band was a new song, Roll Away The Stone, which they confidently banked for future use.

Mott’s fourth US tour began in Chicago on July 1. The major date was New York’s Felt Forum, which saw every ligger, scenester and guttersnipe descend on the after-show party (including Iggy Pop, who fell through a glass door). The band themselves were less than happy when they were refused admission to their own bash.

On August 19, Mott played Washington DC. It would be Mick Ralphs’ last show with the band. The guitarist was uncomfortable with the way the success of All The Way From Memphis had changed the direction of the group. “We’d become a stylised pop group without the outrageousness,” he says.

It didn’t help that he was writing songs which, Hunter told him bluntly, didn’t suit the singer’s voice. “I wanted to move on because I felt I’d outgrown the thing and wanted to work with someone who could sing my songs,” Ralphs says. “I was getting frustrated because I had a lot of songs, like Can’t Get Enough and Moving On. Ian’s voice became a sort of trademark since …Dudes, so was there in the subsequent songs that he wrote, which didn’t leave a lot of room for my songs.”

Post-Mott, Ralphs formed Bad Company with ex-Free frontman Paul Rodgers. Ironically, that band’s commercial success would dwarf that of Mott, especially in the US.

Ralphs’ replacement was former Spooky Tooth guitarist Luther Grovsenor. The fact that he was a childhood friend of the man he was replacing ensured there was no animosity. He also happened to be a top-drawer nutter who would bring an unhinged energy to Mott’s stage show.

The only snag was that Grovsenor was still contracted to Island, so he was forced to use a pseudonym. British singer-songwriter Lynsey De Paul, a friend of the band, had once christened Mick Ralphs ‘Ariel Bender’ after watching the drunken guitarist charge down a street in Germany bending car aerials, before plunging his head into a horse trough. Hunter remembered the name, and laid it on the up-for-anything Grovsenor.

After speed-learning the set in five days, Ariel Bender made his debut with Mott in LA. Stateside, Mott were bigger than ever – their support bands included Aerosmith, REO Speedwagon, Kansas and Blue Öyster Cult.

In November they released their last single to feature Mick Ralphs. Recorded back in July, Roll Away The Stone was another immaculately produced pop confection, complete with While My Guitar Gently Weeps-indebted guitar intro and ‘Sha-na-na-na-push-push’ backing vocals from The Thunderthighs. It reached No.8, leading to another appearance on Top Of The Pops.

“I did feel I had the formula now,” says Hunter. “The Rolling Stones had the formula for God knows how long. We had it briefly for a couple of years. It’s a great feeling.”

On November 12, Mott commenced what would be their biggest and most successful UK tour yet, supported by a rising band called Queen, then promoting their debut album. I hadn’t seen Mott live since they played as a four-piece at Friars the previous February, and I caught them at Oxford’s New Theatre. It was like watching a new band in terms of spirit, confidence and good old-fashioned rock’n’roll excitement. Bender careered around the stage, jousting with Hunter and living up to his declaration that he’d give Mott a shot in the arm.

A month later, on December 14, they brought the tour – and their year – to a close with a riotous show at Hammersmith Odeon, watched from the wings by David Bowie and Mick Jagger. When the band overshot the curfew, the safety curtain was lowered, only for it to be blocked when Morgan Fisher shoved the venue’s grand piano under it while the band roared on, Overend Watts’ bass getting trashed in the process. It was a fitting end to Mott’s golden year.

Of course, the wave had to break. The electrifying buzz which Bender brought to the live show didn’t translate to the studio, so Hunter had to bear the full weight of being leader, songwriter and producer.

Still, when I visited them at Advision studio to watch them record the follow-up to Mott they were on fire. Over the course of an all-night session, I witnessed Morgan – by now a full-time member – lay some phenomenal Hammond organ on a Hunter hooker narrative titled Alice, and Bender attack the power chords on Marionette before adding his strangled-donkey solo. At one point he put down his guitar and casually took a leak in the sound booth.

Mott’s seventh album was released in March. Its title, The Hoople, suggested that it was a companion piece to its predecessor. Despite the presence of Roll Away The Stone (with new guitar overdubs from Bender), the life-affirming single The Golden Age Of Rock’N’Roll, the epic Marionette and the proto-punk Crash Street Kidds, with hindsight the album lacked the cohesive drive of Mott (although I believed it when I told the Sea Divers it was the band’s best yet).

Something had irrevocably changed in Mott. Later in the year, their non-album single Foxy Foxy bombed, and Ariel Bender left the group and was replaced by Mick Ronson. Although the rehearsal I saw at a Fulham sound staged boded well – even with the band shockingly sporting shorn short hair – the re-reconfigured Mott didn’t get past a Scandinavian tour before buckling under intra-band tensions and the failure of their gorgeous swan-song single, Saturday Gigs.

I’ll always remember Ian’s emotional teatime phone call to say he’d left. “I just sat down and decided I couldn’t do it,” he said. “Tell the fans, I’m so sorry.” That last newsletter was heartbreaking to write, as my teenage years ended along with that band.

In 2009, 40 years after they formed, the original Mott line-up reunited for five glorious gigs at London’s Hammersmith Apollo (née Odeon). Now they’re about to do it again, four decades after Mott placed them up there with the greats.

Me, I’ll always be that wide-eyed kid in the playback room where this band are concerned. As Ian Hunter eloquently put it in Ballad Of Mott The Hoople: ‘So what the hell?/I can’t erase the rock’n’roll feeling from my mind.’ Some of us have never tried to.

This article originally appeared in Classic Rock #191.

For more on Mott, not least the making of Roll Away The Stone, then click the link below.

The Story Behind The Song: Roll Away The Stone by Mott The Hoople