It was difficult to reconcile the emaciated figure lying there among the plastic tubes – the medical equipment beeping intermittently – with the familiar face of Phil Lynott, one the great lost vagabonds of the western world. His estranged wife Caroline, face etched with worry, was at his bedside. By her side was her father, the TV host Leslie Crowther, his hand tightly clutching hers as the clock kept a ticking vigil and the night crept towards another day.

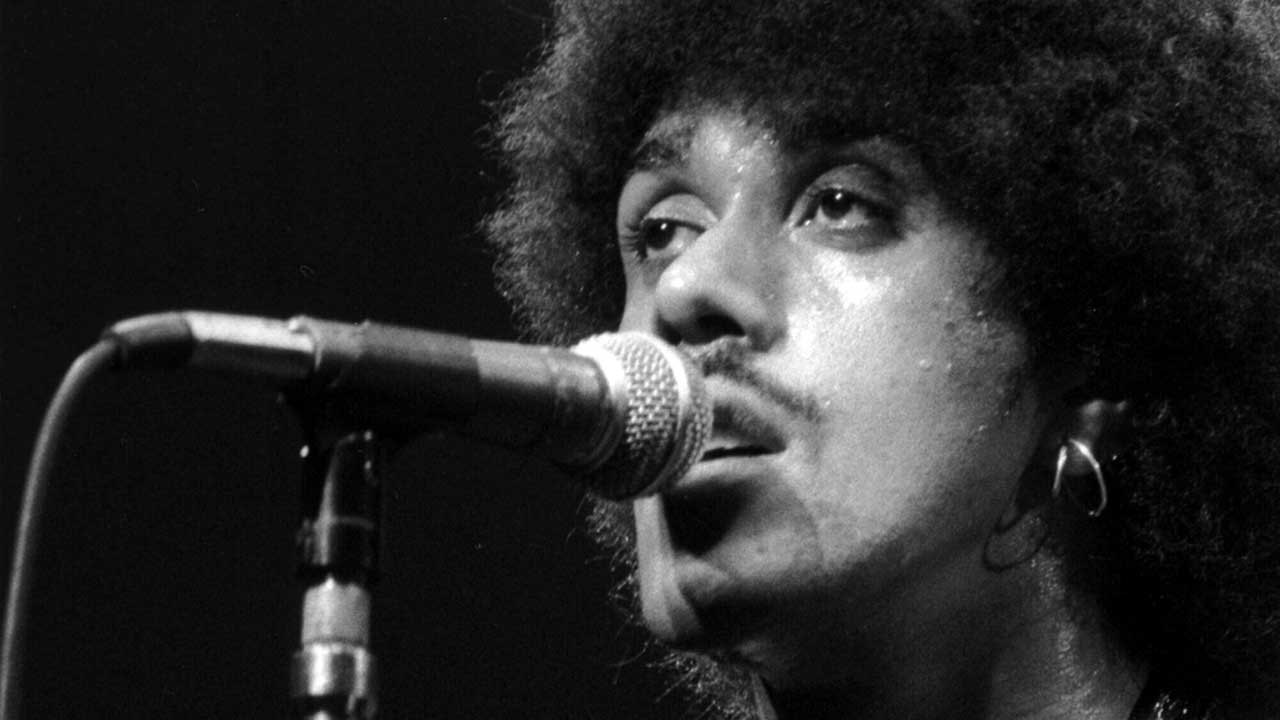

How did it get to this? Arguably one of rock’s most charismatic and eloquent singers and songwriters, struck dumb by drink and drugs. The man who sang about dancing in the moonlight, or being down on his luck in Hollywood. The man who escaped dire poverty in Dublin to take Thin Lizzy rolling around the world until they called it quits (after bowing out with the highly successful Thunder And Lightning tour) in 1984.

Philip Parris Lynott, born to a Brazilian father and an Irish mother, played the bars of Dublin with Skid Row and Orphanage before settling on a Thin Lizzy line-up featuring Eric Bell on guitar and mainstay drummer Brian Downey at the start of the seventies.

With fluid membership and inconsistent output, the band's inspired take on the traditional folk song Whiskey In The Jar saw them flirt with early fame, but it wasn’t until 1976’s Jailbreak and the dazzling The Boys Are Back In Town that they found success in the US. It was fickle fame at that, and the only time they’d fly so high in America.

By the time Thin Lizzy split up in 1984, Lynott had already released two solo albums to a largely indifference audience, 1980’s Solo In Soho and The Philip Lynott Album two years later.

Though neither was received with the enthusiasm of his work with Thin Lizzy, both records showed glimmers of promise, with the arch Lynott lyricism on show in songs like Dear Miss Lonely Hearts, Old Town and the pitch-black Fatalistic Attitude, while Yellow Pearl would introduce Top Of The Pops for the first half of the 1980s.

His post-Lizzy band, Grand Slam, propped him up as a live fixture at festivals and club gigs throughout 1984, and he’d even record a hit in 1985 with his old Lizzy sparring partner (literally at times) Gary Moore, with the rousing anti-war anthem Out In The Fields.

While these musical cameos flickered in and out of life, Lynott was spiralling slowly out of control. Heroin and alcohol dependency made for a shambolic figure shuffling through Soho. His sporadic appearances at the Marquee Club through 1985, as a punter propping up the bar – not the musical firebrand storming the stage with a mirror scratch-plate on his bass guitar – caused quiet concern among the regulars.

Ashen-looking and turning gaunt, an old photographer friend of mine described his skin tone as grey, while Eric Bell would later tell me about the time he last saw Lynott, in west London. He barely recognised his old friend as he exited a shop, arms full of groceries. “We said we’d meet another time,” said Bell, “But that was the last time I ever saw him.”

There was a suggestion that Lynott was working on a new album, but what was clear was that as Christmas approached, Lynott was retreating in on himself, drinking and drugging on a daily basis.

Lynott's body finally gave in on Christmas Day. He collapsed at home in Kew, and while his two daughters Sara and Cathleen were at the house, it was his mother, Philomena, who discovered him and called his estranged wife.

Caroline jumped in her car and drove the 100 miles from her home in Bath to be at Lynott’s side. Familiar with his habit, she rushed him to a drug clinic at Clouds House near Shaftesbury, where the clinicians took one look at the ailing Lynott and sent him quickly on to Salisbury Infirmary. There he was diagnosed with septicaemia (poisoning of the blood), as well as kidney and liver damage.

Although he regained consciousness and was able to speak to Philomena, his condition worsened, and by the start of the New Year he was put on a ventilator to help with his breathing.

Just eleven days after his collapse, on January 4 1986, he died of pneumonia and heart failure at the hospital's intensive care unit. He was just 36.

Phil Lynott's funeral was held at St Elizabeth's Church in London five days later, and was followed by a second service at Howth Parish Church in Dublin, on January 11. He was buried in St Fintan's Cemetery, Dublin.