Though there are some who champion a rather narrow interpretation of the subgenre, black metal has long been characterised by an incredible degree of plurality and diversity, resulting in numerous contrasts and contradictions. In fact, almost from its very beginning, black metal’s development has been explicitly informed by the combination of conservatism and a more experimental and revolutionary impulse.

As with many emerging musical movements, the scene was originally made up of a small, fragmented and loosely connected collection of bands, making diversity inevitable. Interestingly, though, this characteristic survived the intense process of unification that occurred in Norway during the early 90s. Scene godfather Euronymous may have famously urged a uniformity of appearance and ideology, but his eclectic musical taste meant that no attempts were made to streamline black metal’s sound in that era – indeed, by defining the genre solely by its Satanic ethos, Euronymous actually freed many musicians creatively.

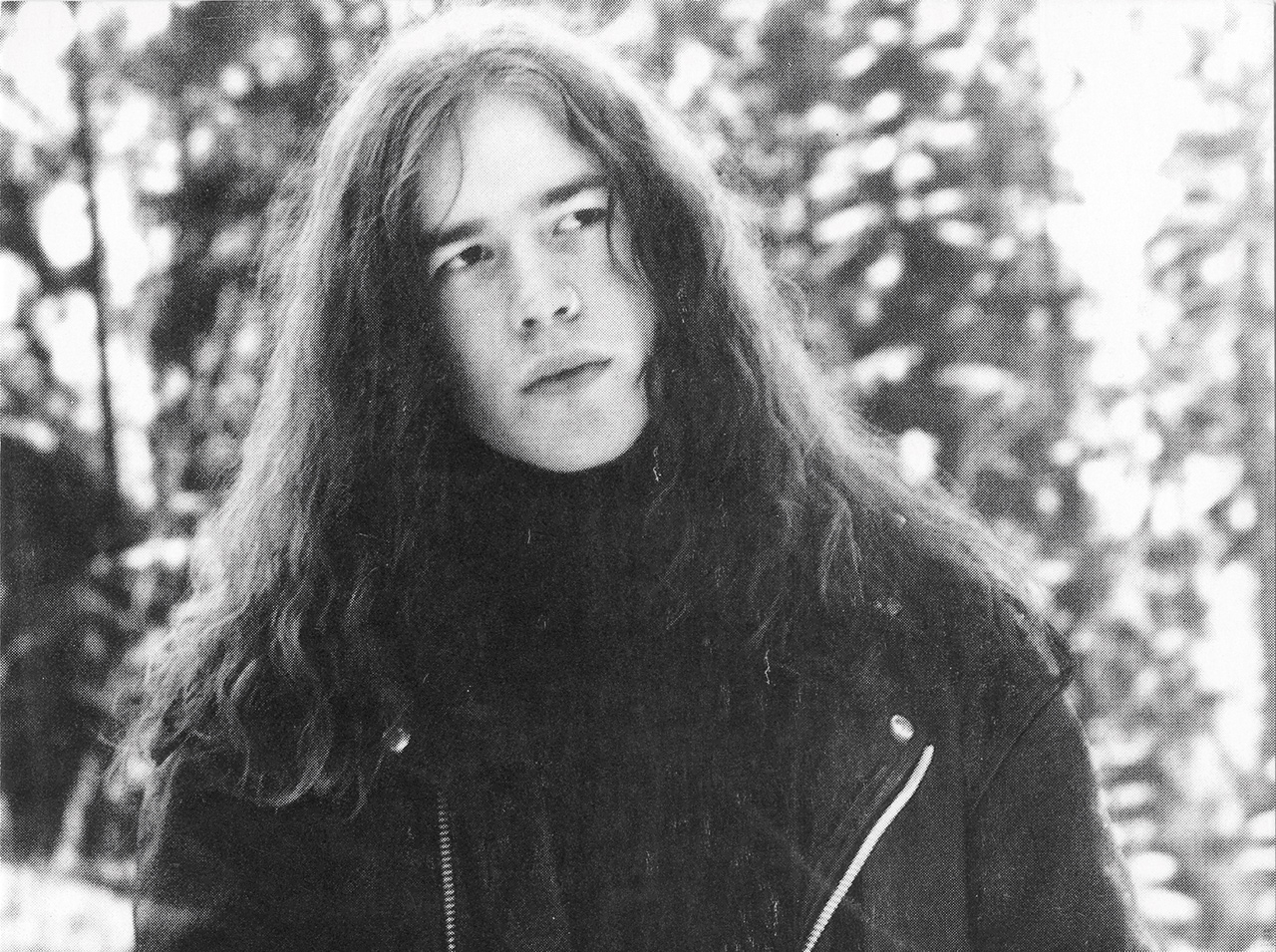

To an extent then, almost all the early black metal bands could be considered avant-garde; early Mayhem, Darkthrone and Burzum recordings may encapsulate black metal’s core values for many today, but those works were highly innovative, even if those innovations soon formed a template for many later groups. As Garm, aka Kristoffer Rygg, of Ulver states, at the time it really was seen as imperative for bands to be unique.

“I think in those days that was a major criterion; to be a force to be counted on in the scene, you had to create your own thing. This latter-day perception that true black metal only sounds like Darkthrone is just fucking silly, it’s a lot of distortion on the original idea, which included stuff like Mercyful Fate, for crying out loud. The charisma of the music was really paramount. I fondly remember the first Samael and Master’s Hammer albums or the Rotting Christ/Monumentum split single – they all sounded very different to one another, but we loved it all the same.”

Nonetheless, there was a clear divide between the likes of Ulver and Arcturus (two bands that Garm fronted at the time) and the more established Norwegian black metal bands such as Immortal or Darkthrone. Much of this had to do with a willingness to incorporate non-metal elements into the music, something that horrified more traditional metal fans at the time, but which has long since become a defining aspect of the black metal scene. For Ulver that would be folk music; for Mysticum industrial and techno strains; for Arcturus classical and prog elements and so on.

Thus around 1993⁄1994 factions within black metal began immersing themselves even deeper in an unambiguously progressive and experimental period, partly as a reaction to copycat bands adopting the Mayhem/Burzum/Darkthrone approach. Perhaps for that very reason – or perhaps simply because it had the largest pool of musicians at the time – the majority of explicitly avant-garde acts would end up being bands from Norway.

Kristiansand’s In the Woods… were one such entity. Debuting in 1993 with the Isle Of Men demo, and following it with 1995 debut album Heart Of The Ages, the outfit integrated folky strains and prominent prog and psychedelic overtones (later the band would tellingly release covers of Jefferson Airplane, Pink Floyd and King Crimson).

“There was a focus,” explains drummer and co-founder Anders Kobro, “it was supposed to be elitist and you had to have your own identity, that was extremely important. We couldn’t allow ourselves to sound like this or that. Black metal was already trendy in ’94,” he continues. “We followed the rule that you couldn’t sound like anyone else. It was a very strict idea then; do your own thing, don’t try to copy anybody else.”

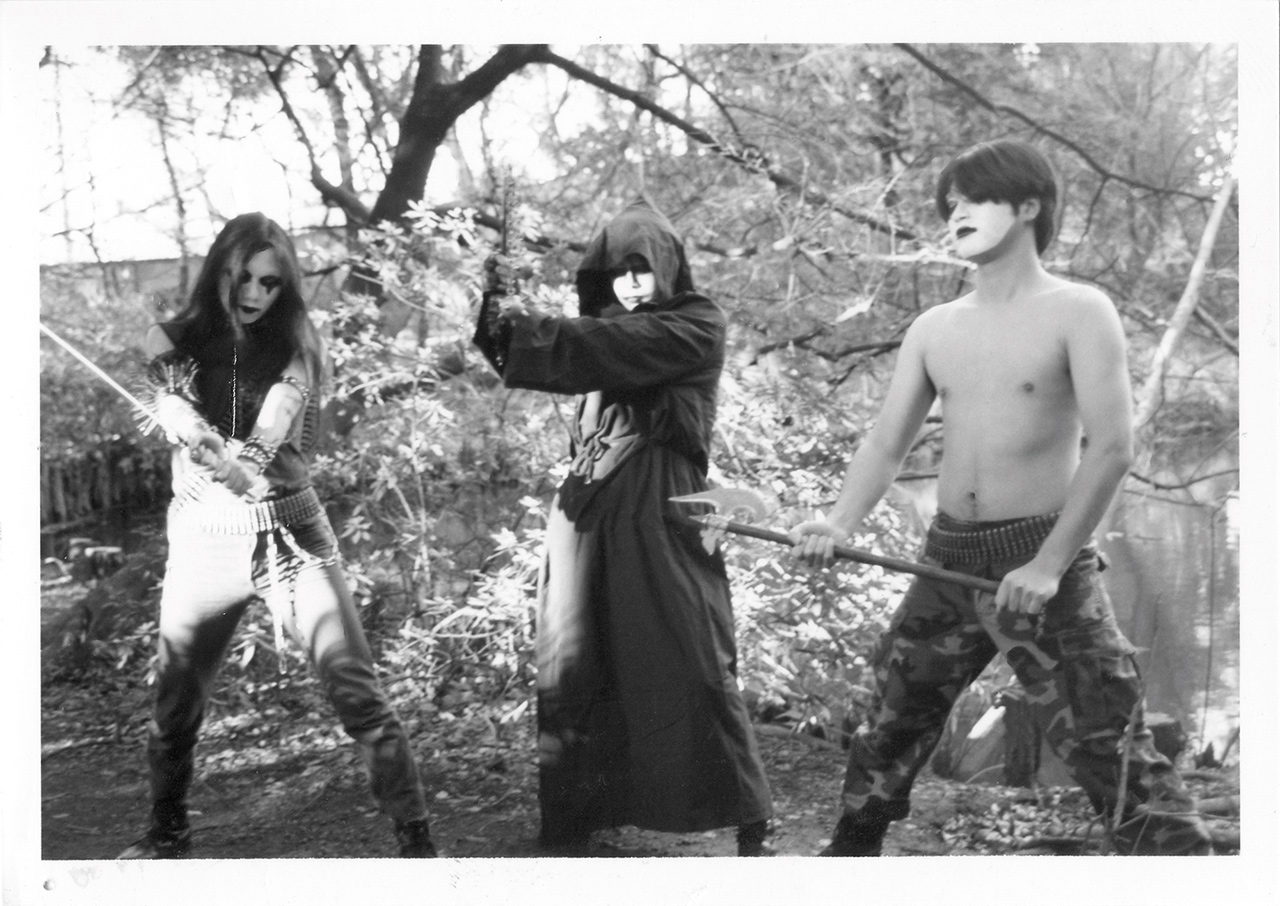

Parallels can be drawn between In The Woods… and Fleurety, another Norwegian group on the very fringes of the scene, both geographically and socially. In their case, their outsider status and unique approach would cause them to be berated and even threatened by several of their countrymen, including Ulver (the two bands have long since buried the hatchet). Nevertheless, their 1995 debut full-length, Min Tid Skal Komme, remains a milestone work that arguably predated the post-black metal sound of bands such as Agalloch and Alcest by a decade. Folk-inspired acoustic guitar passages, desolate riffing and blasting drums combined with unconventional song structures, psychedelic guitar work, unusual jazzy time changes, near-funk bass work and haunting female vocals. And if anything the band became even more experimental with 1999’s Last-Minute Lies and the recordings that followed.

“I think there was a rather upfront psychedelic prog 70s influence, a certain jazz influence, a certain folk music influence… and of course black metal!” says Svein Egil Hatlevik, one half of the duo. “We were listening to Pink Floyd and King Crimson and got the jazz influence indirectly from that sort of music. It might have something to do with the general isolation we were in, but we had our own perception of what kind of music we wanted to make. That was one of the rules or guidelines that you could get from the first years of black metal, that if your music or band sounded like some other band you were worthless and there was no reason why you should release records… One reason why you can say the movement did stagnate was you had certain benchmark releases, milestones, a lot of the albums by Darkthrone, for example, and people thought, ‘Ah, this is how black metal is supposed to be.’ The music people made became more streamlined.”

Yet in reaction to this were many stunning bands who forged their own sound. Oslo’s Ved Buens Ende would demonstrate a groundbreaking approach that would only be hinted at a decade later via acts such as Deathspell Omega, with the 1994 demo Those Who Caress the Pale and the 1995 full-length, Written in Waters.

Drawing on influences as diverse as jazz, folk, and prog rock – as well as second-wave black metal – the wonderfully bleak compositions still sound fresh today, the (mostly clean) vocals, dissonant riffing, angular percussion, and challenging time signatures combining to offer a level of complexity all but unexplored at that time.

The aforementioned Arcturus would bring avant-garde black metal to a greater audience thanks to 1997’s La Masquerade Infernale, a record that seemed to offer new levels of musical and intellectual sophistication and which utilised everything from classical musicians to electronic breakbeats.

Countrymen Solefald would follow a similar path the same year with debut album The Linear Scaffold. It had musical parallels to La Masquerade… but replaced the historic overtones with a post-modern approach that took inspiration from French existential writer Jean-Paul Sartre, urban architecture, modern transportation, and television – elements purposely ignored by a scene that consciously rejected modern society and its trappings.

Clearly 1997 was clearly the peak of such undercurrents, with Japan’s Sigh knocking the ball out of the park in terms of experimental eccentricity with their Hail Horror Hail album. Black metal still formed the foundation of the band’s music, but on top of this was a strange cut-and-paste juxtaposition of orchestral elements, blues rock lead guitars, discordant synths and dizzying psychedelia, the combination of which led label Cacophonous to place a disclaimer on the sleeve warning listeners that any perceived strangeness was because the listener’s “conscious self is ill-equipped to comprehend the sounds produced on this recording”.

By the close of the decade even the more established black metal bands felt obliged to push more modern elements into their sound, as seen by the likes of Gorgoroth, Mayhem, Gehenna, Satyricon and Dødheimsgard, whose 1999 masterpiece, 666 International, perfected a more precise and contemporary/futuristic take on black metal.

Today, a certain degree of avant-garde music within the black metal movement is expected and accepted, as seen in bands such as Deathspell Omega, Dodecahedron, Spektr and Oranssi Pazuzu. But have no doubt: this is a direct result of those fearless pioneers of the 90s who rebelled against what was in danger of becoming an increasingly streamlined genre.

SECTIONS OF THE INTERVIEWS ARE TAKEN FROM THE BOOKS BLACK METAL: EVOLUTION OF THE CULT [2013, FERAL HOUSE] AND CULT NEVER DIES: THE MEGA ZINE [2016, CULT NEVER DIES]

The blight fantastic

Three groundbreaking 90s avant-BM tracks

Fleurety - En Skikkelse I Horisonten (from Mid Tid Skal Komme, 1995)

Split into two parts, this epic track weighs in at over 11 minutes in total and takes the listener on a bewildering yet exhilarating journey through tranquil acoustic guitars, haunting female vocals, lengthy and emotive riffing, technical and angular guitarwork, discordant musical insanity, jazzy time signatures and straight-up, seething black metal aggression.

Mysticum - Kingdom Comes (from In The Streams Of Inferno, 1996)

Relentlessly driving with a relatively simple melody at its core, Kingdom Comes takes familiar icy Norwegian riffing and propels it forward with almost danceable drum machine patterns. The memorably eerie organ break that creepily builds the tension before breaking into a truly epic and haunting pay-off is the icing on the cake.

Sigh - Hail Horror Hail (from Hail Horror Hail, 1997)

The opening title track of Sigh’s third album explodes in a frenzy of upbeat, blues rock leads and catchy riffing, making Mirai’s frenzied screaming and slasher-esque lyrics all the more disturbing. The song soon lurches into a serene orchestral piece, before collapsing into cacophony and finally returning to the opening riff.

The 90s issue: Your definitive guide to the craziest decade in metal