A couple of years ago, Myles Kennedy turned to Jim Carrey for some life-changing wisdom. The mercurial Hollywood star, a “genius” in Kennedy’s eyes, had announced his retirement from acting, when he said this: “I have enough. I’ve done enough. I am enough.” For the Alter Bridge frontman, a lifelong worrier learning to manage his anxieties, it parted a lot of internal clouds.

“When I heard him say that, it was like: ‘Wow, there’s somebody who’s figured it out,’” Kennedy says now. “It’s like, just be here, just be grateful for what you have, let go of all that other stuff.”

In a strange way, there’s something in Kennedy’s gentle, sharp-cheekboned look – brightened easily with a wide smile – that’s not a million miles from Carrey. The Mask one moment, Eternal Sunshine Of The Spotless Mind the next. Committed performers coming to terms with fearsome inner critics. For Kennedy that process – coupled with a nod to Bruce Lee’s ‘be like water’ philosophy – comes out in his third solo album The Art Of Letting Go.

“He [Carrey] has got versatility as an actor, as a comedian,” Kennedy enthuses. “That’s why he’s one of the all-time greats, in my opinion, because he’s able to cover so many different bases. I aspire to that. I mean, I don’t feel like I’m nearly at his level in what I do, but I work at it, and I like to explore different sounds and do different things.”

If Kennedy’s first two, more acoustic-based, solo records – 2018’s Year Of The Tiger and 2021’s Ides Of March – were about facing his personal demons, The Art Of Letting Go is the sound of him releasing those demons. A collection of heavy rock songs, mostly written in early 2023 (with the exception of two beautifully nuanced, softer moments – Miss You When You’re Gone and Eternal Lullaby, kept over from the Year Of The Tiger days), it opens on a juicy, bluesy lick that sets the tone for the anthemic matter to come.

Created with his three-piece solo band in mind (more on them shortly), and with longtime collaborator Michael ‘Elvis’ Baskette producing, it’s riffy yet brooding. Blues-based where Alter Bridge are more metallic, although there are moments that wouldn’t feel out of place on an Alter Bridge record, the mighty, Mark Knopfler-inspired riffage of single Say What You Will being one of them.

“I just felt like it was time,” Kennedy says of the record’s beefier nature. “And I think to some degree it was from an interview I did a long time ago, we were talking about how I approach the solo realm, and I made a comment about a song I had that was more rock-based, and I said: ‘Well I can’t do that in this realm.’ Afterwards I thought: ‘Why am I boxing myself in? Making solo records should be about exploring, right?’ And so the light bulb went on, like: ‘Let’s make a rock record!’”

When it comes down to it, most frontmen and women – even the nice ones – are pretty narcissistic. Once you hit a certain level, it’s difficult not to be. Even on today’s relatively more conservative budgets, the business of performing to fans, talking about yourself constantly (during interviews, on stage, via social media) and being surrounded by people whose job it is to ensure the successful running of your band… Well, it tends to breed a certain type.

Kennedy might be one of the rare exceptions. A very well-oiled interviewee who also chats like someone you might meet at a gig, he’s something of a unicorn in rock-star circles. Curious. Pensive. Often a bit goofy. Quick to take notes from people. Genuinely happy for his Alter Bridge bandmates’ success in the recently reunited Creed (more on that later). It says a lot about him, and the way he looks at life these days.

“One of my favourite bodies of work was when Ella Fitzgerald covered the Gershwin classics,” he says. “I believe it’s in Nice Work If You Can Get It. There’s something in that about [the fact that] time will ultimately erase your name. As I get older, it’s like: ‘Hey man, relevance is not something you can take for granted.’ Ultimately, you realise that people will forget about you. How are you going to be with that? Your whole identity is this, what are you going to do?

"So it’s asking those big questions. To some degree there’s a bit of that emotional gravity on this record, coming to terms with that sort of thing.”

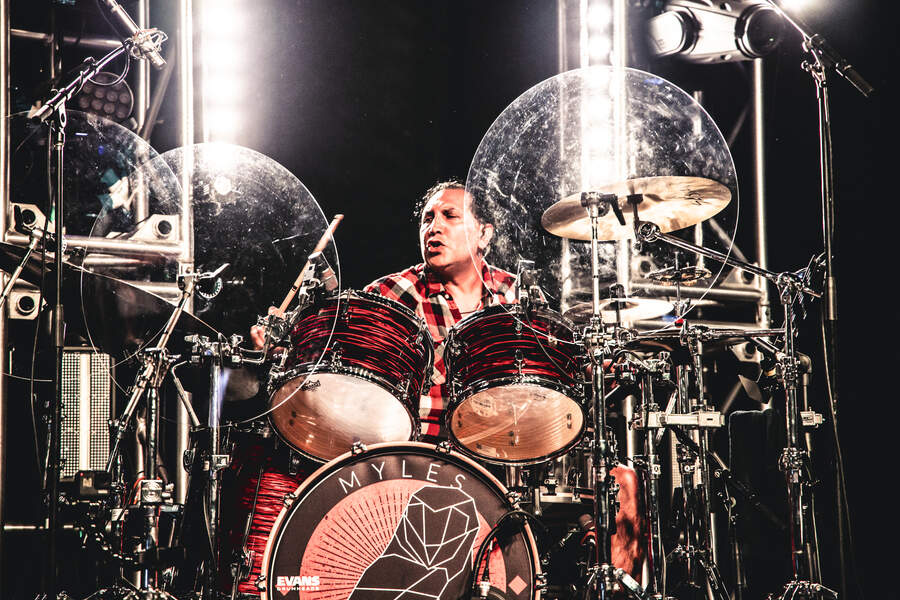

The Art Of Letting Go might reflect Kennedy’s recent mental journey, but it also has firm roots in his past. For starters, drummer Zia Uddin is an old friend from high school in Spokane. By the mid-80s they’d started their first rock band and were playing (underaged) in bars, hosting keggers, and rolling sleepily into class the next day. You can hear tastes of that energy, that enjoyment, in these new songs.

“Zia would set up these keggers, and you charge your friends a few bucks to show up,” Kennedy recalls. “I mean, I didn’t drink at the time, so I didn’t really care about that. But it was just nuts the stuff we would do, just because we wanted to play. We just wanted an audience. We had a lot of fun.”

A quiet, naturally anxious kid (in sixth grade he was given the class ‘worry wart’ award), Kennedy stayed in his room learning Jimmy Page solos when his friends went out drinking. “I discovered alcohol like ten years later,” he adds, “and then kind of went through a ‘period’, let’s just call it that, where it’s like: ‘Oh, this is great!’. Now I barely drink at all.”

The third corner of his solo trio, bassist Tim Tournier, comes from a similar musical school of thought. Alter Bridge’s manager by day (he also manages Kennedy and Mark Tremonti’s solo operations), he was mentored by Frank Sinatra guitarist Dan McIntyre before going to Berklee and winding up in various bands. Another rocker with jazz DNA, in other words.

“And Zia and I were in [the school] jazz band together,” Kennedy adds. “And I got a degree in Jazz Studies, so I’m a total jazz nerd as well.”

Not that you’ll hear much jazz on The Art Of Letting Go, although perhaps there’s a small nod to it in Kennedy’s knack for subtle, surprising little shifts in tone (e.g. the pre-chorus minor key dip in Miss You When You’re Gone, the delicate, Red Hot Chilis-esque beginning of Behind The Veil that grows into a big, biting rocker). The sort of dark and light shades that reveal themselves throughout the album.

“I didn’t want it to be like a Disney record,” he says. “You know, all positive and [adopts cheesy voice] ‘Oh, the Art Of Letting Go!’ I wanted the struggle, the yin and the yang of it, to come through.”

Indeed, for all its oomphy power-trio energy, the contemplative, darker notes of The Art Of Letting Go aren’t hard to find. Mr Downside nods to Kennedy’s “prince of darkness, glass-halfempty” side. How The Story Ends (inspired by the 2022 horror film Speak No Evil) is a cautionary tale, warning against the pitfalls of compulsive people-pleasing. So why now? What brought on this shift in perspective?

“I think getting older, to some degree,” he muses, “and realising that you have a finite amount of time on this planet. And do I want to wake up every morning and worry about things? No.

“I feel like I’m getting a better handle on it,” he adds. “There’s still times when that internal negative voice will have its way, but I’m getting better at learning to shut it off. That’s become paramount to me, just learn to roll with the punches, don’t get so attached to things, everything’s going to be alright. That’s had such a profound effect on who I am, and my quality of life. I wish I would have discovered some of these approaches decades ago.”

Decades ago, Kennedy was teaching guitar and playing in The Mayfield Four (with Uddin on drums). He watched with the rest of America as a Florida band called Creed became a phenomenon. Hugely successful and equally polarising, his Alter Bridge compadres’ former group had the sort of megabucks, stadium-filler ride that AB have never had.

As history has shown, at the time at least, it didn’t exactly pan out happily for the band. On The Art Of Letting Go, the moody stomp of Nothing More To Gain alludes to that idea of seeking the next dopamine rush; the next success, next ‘thing’ that’ll make us happy, or so we think.

“I don’t think I’m hard-wired for that [level of fame],” Kennedy says. “I see young artists like Billie Eilish and Finneas, I think they are just genius-level composers and musicians, but it became so massive…”

He pauses, suddenly sounding very dad-like.

“And I think: ‘Wow, I hope these young people have the skill-set to deal with the things that come with that.’”

Naturally he and Alter Bridge have talked about Creed’s earlier days, not least of all in light of the band’s reunion tour and anniversary reissue activity – of which Kennedy is totally supportive.

“They were in their twenties, they were just kids when it blew up,” he says, quickly but sincerely adding: “And I will say it’s freaking beautiful that they’re getting this third chance, and it’s happening and it’s going gangbusters. And I pray that it keeps going and going, because I think it’s great for them. It’s great for the fans to hear the songs. It’s making people happy.”

At the same time, his ‘other bandmate’ Slash has returned to the group that made him famous (not to mention rich), as Guns N’ Roses have continued to tour and put out whispers of new music. Even for someone as grounded as Kennedy, you can’t help wondering how it feels watching his friends go back to their ‘first’ bands. Isn’t it a bit like watching your wife go for dinner with an ex?

“I think it would be disingenuous not to say that, initially, it’s kind of like… Yeah, that’s actually kind of a good analogy. But when you step back and really look at the situation, especially for somebody like myself, I’m at a different place in life now than I was even ten years ago.

“And, you know,” he adds, “in a lot of ways, [Creed] were responsible for opening doors for Alter Bridge and all that. So it’s great that they’re back in that world again. It allows me to make more solo records, you know it’s… it’s all, good. I hope they make records, I hope they tour a lot more. There’s space for all that to co-exist.”

For Kennedy, it seems, that’s the real dream. Not being tied to one project or place (he talks about one day doing some sort of Ella Fitzgerald tribute, travelling to Kyoto, seeing the Pyramids). Playing to packed arenas, but still able to go grocery shopping unrecognised. Having three sets of bandmates that all feel like brothers. “

A lot of people try to [ask you]: ‘Which one’s your most important one?’” he says. “Honestly, I feel the same emotion for all three, because it’s a personal thing.”

It might be fair to say that Kennedy’s greatest obstacle has always been himself. That anxious inner voice. Some grain of darkness, probably there since his father died (when Kennedy was just four). The passage of time, a lot of reading, conversations with his wife and some lifestyle changes – he now meditates every day without fail – reflect a man learning to let things go.

“The same way I’d go to a gym and try and improve my cardiovascular system by working out hard,” he reasons. “It’s the way I look at my state of being – I can always do better, I can control this crazy thing, the human brain, which can run you all over the place, and the internal voice in there can…”

He laughs a little manically, nerves coming back into his voice.

“It’s like a crazy person lives in there sometimes.”

Maybe you have to be a little crazy to be in a rock band in the first place. Maybe ‘the art of letting go’ is really about accepting all of life, to the full. Beyond its carefree, motivational-quote veneer, it’s an idea (and an album title) that points to something more complicated and interesting: life can be really hard, it can be wonderful, it can be a lot of things.

“I just don’t want to have to spend the rest of my life worrying: ‘Did I say something wrong?’ ‘Did I offend that person?’ But that’s part of the art of letting go, right? I’m learning to shut that voice off. And that’s hard, because by trying to do that it’ll sometimes want to talk more. But that’s part of the practice, right?"

The Art Of Letting Go is out now via Napalm