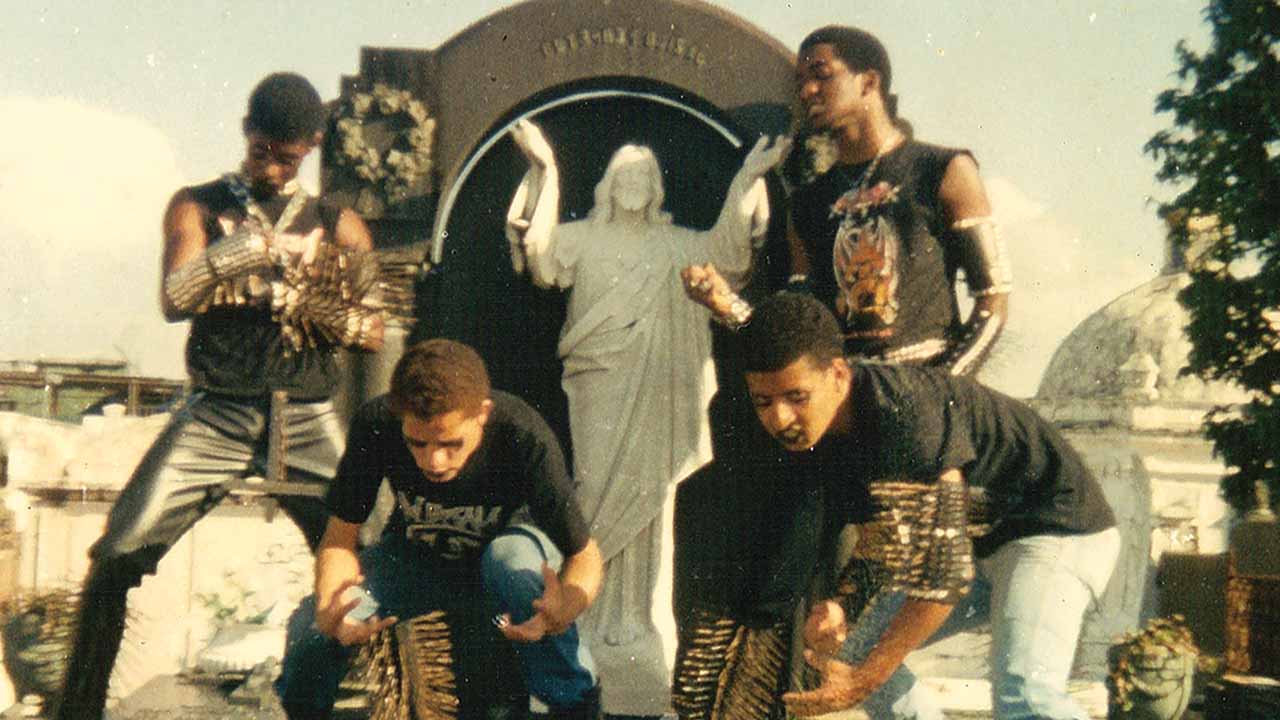

The awe has its own force of gravity. The three members of Mystifier have made a pilgrimage to the Cemitério do Bonfim in Belo Horizonte, nearly 800 miles south of their hometown, Salvador, that sits on Brazil’s east coast. Amid row upon dense row of gothic gravestones and mausoleums stands a structure that has become the most potent epicentre of the country’s underground metal scene and beyond. Flanked by two dark pillars holding up an imposing arched shrine, a contrasting white marbled, crucified Christ looks down, as if in mourning for the act of blasphemy that was carried out under its shadow. It was here in 1987 that four bullet-belted, ghoulishly made-up teenagers shot the cover for the album without which Mystifier, and a host of other bands now sworn to the dark, would not exist: Sarcófago’s landmark black/thrash debut, I.N.R.I..

Band founder and guitarist, Armando ‘Beelzeebubth’ da Silva Conceição, vocalist, bassist and keyboard player Diego DoUrden and drummer Eduardo ‘Warmonger’ Amorim are being filmed for an online documentary on Mystifier, Dois dias na Capital do Metal da Morte (‘Two Days In The Capital Of Death Metal’). Across its 46 revealing minutes, it’s made clear that their deep and profound connection to their roots is inseparable from the multi-faceted, often contrarian and trailblazing path they’ve travelled since their formation two years after I.N.R.I.’s release. “To talk about emotions is quite easy, right, my brothers?” muses an overcome Beelzeebubth. “To talk about sensations is a little difficult.”

- The best Amazon Prime Day whisky deals 2020

- The best metal guitars 2020: Get ready to shred with our essential list

- Shop for the best Bose deals

- Loudest Bluetooth speakers: the best speakers for maximum noise

Before I.N.R.I.’s release, Beelzeebubth had been a diehard fan of Sepultura. Their original lead vocalist, Wagner Antichrist, had abandoned them for Sarcófago, starting an inter-band feud in the process. Inspired to form a band of his own, in part a homage to the sacrilegious, blastbeating frenzy of his newfound heroes, Beelzeebubth took Mystifier into even darker, more primitive places over the course of two demos and their 1992 debut album, Wicca. The bestial roars of then-vocalist Meugninousouan seemed to emanate from another realm, tapping into the kind of abyssal atmospheres that had been both early death and black metal’s unholy grail, granted only to those whose sense of purpose was willing to go beyond the realms of the rational. The band even staged their own, I.N.R.I.-inspired photoshoot featuring a blood-stained Christ crawling with an equally blood-splattered cross as the band carried flaming torches behind him.

“I was only 18 years old when we took that picture for the back cover of Wicca,” Beelzeebubth recalls. “I wanted to take the most extreme shot that any band on the planet had ever done! Several people stopped their cars to watch us as we did the shoot. A friend brought a dog to the session for some reason, and some Christian people said that it was blasphemy and called the fuckin’ cops. But it was liberating. It was a time of many discoveries and many realisations in my life.”

If the release of I.N.R.I. was a watermark for some, not everyone was onboard from the off. “They were different times,” says Beelzeebubth. “Some thrash, death and grindcore bands did not support or like black metal bands. Sarcófago faced a lot of rejection by that audience, mainly for the rivalry with Sepultura. It took time for Brazilians to open their minds to bands like us, Sarcófago, Vulcano, Impurity and others.”

In the early 80s, the Brazilian underground was riven by factions: within cities, between cities, and between rival scenes. The military dictatorship that ruled over Brazil from 1964 to 1985, and the extreme levels of poverty that were deeply entrenched throughout the country, all created a violence-primed backdrop that was reflected in the raw, visceral nature of the music of that time.

“The tribalism was very strong here in Brazil, for sure,” says frontman Diego. “The skinheads had the Nazi guys and they were against the punks. But eventually the metal guys joined the punks and the hardcore people to fight the Nazis, because the skinhead guys were the real evil guys. If there are still a couple of them nowadays, they are afraid of coming out. Nobody ever sees a Nazi at concerts anymore.”

The year of Mystifier’s formation, Sepultura released Beneath The Remains, the album that, despite the inroads Sarcófago had made, truly broke out of the Brazilian scene and made them an international sensation. As much as thrash, with its roots in social upheaval, had always been embedded in the Brazilian underground, their transition from the dank, deathly approach of their early years left the remaining Brazilian bands with ambivalent feelings.

“Some of the bands tried to change a little bit to try out this new formula that Sepultura had, and some of the extreme people got upset because they were getting out of the Satanic extremity of the first two records,” says Diego. “But back then it was so difficult to get into the international market. It was a game of luck and contacts. So when Sepultura became famous, it was actually good for us, because the Brazilian scene stood out to the world. You could even say that it helped Mystifier because we were found by Osmose Productions after that.”

Released by the French underground label, Mystifier’s following two albums, 1993’s Göetia and 1996’s milestone The World Is So Good That Who Made It Doesn’t Live Here, saw the band become a cult act worldwide while consciously refusing to fall into standard black metal tropes. Even the use of keyboards, along with the operatic vocals on The World Is So Good…, forged their own, adversarial bond with black metal’s founding, undiluted ideals.

“I don’t like to repeat the same old formulas,” states Beelzeebubth. “I am always looking for new sources of inspiration. I didn’t want to sound like a traditional Norwegian band, as many were doing for trading and profit.”

To this day, Mystifier are still a revered act. Last year’s Protogoni Mavri Magiki Dynasteia album – their first in 18 years after a series of line-up battles – drew rave reviews, live shows induced states of feral rapture, and the band were due to embark on a world tour before the COVID-19 outbreak. Proof that uncompromising allegiance to metal’s past need not be cause for stasis, Mystifier’s driving belief in metal’s darkest, most persevering forces is a boundless resource.

“I’m an occultist,” says Beelzeebubth. “I have always been very interested in the mystery about the truth about our existence. I have kept my eyes opened during the night to see in the darkness, and I am devoted to bands that wrote their lyrics about it, such as Slayer, Venom, Possessed and Cirith Ungol. My imagination went from Heaven to Hell.”

“In Brazil,” adds Diego, “Satanism was a rebellious movement. If you look at the Brazilian bands that stood out at the time, everybody was from a poor background. So that condition of being poor and living a very difficult life, a dangerous life, a very violent life in the slums, that gave us the feeling of rebellion against all that was considered ‘right’. That includes the church and the government, so the Satanism was a symbol to be against the system, to be against the ‘good people’ who actually were not good – the rich ones who wanted to dominate and enslave the poor people. It was a symbol of justice for us, to represent our fight.”