In late June last year, we re-posted an epic interview with Nazareth’s Pete Agnew and Dan McCafferty. First published way back in 2004, and conducted over an Olympic-level drinking session in the bar of the Pitfirrane Hotel in Fife, it’s a rock’n’roll yarn that has everything, starting with Agnew and McCafferty, aged five, requesting to share a double desk on their first day at St Margaret’s Primary School in Dunfermline, to them becoming best friends, and the gradual elevation of Nazareth, the band they co-founded in 1968, from wedding group into one of the most underrated and stubbornly persistent hard rock bands that these isles ever produced.

With a grin, McCafferty had revealed how each year on July 1, the anniversary of the band first giving up their day jobs to turn pro back in 1971, either he or Agnew would phone the other to enquire: “D’ya fancy giving it another twelve months?”

With a mix of good-natured humour and genuine astonishment that these things happened at all, the pair dug into a treasure chest of war stories that included being taken under the wing of early producer Roger Glover from Deep Purple, reluctantly teetering on stack heels and dressing up “like bloody Christmas trees” on Top Of The Pops during the era of 70s glam, and the eventual patronage of Guns N’ Roses, whose singer Axl Rose fan-worshipped McCafferty, whose powerful gravelly voice could strip paint from walls.

When Nazareth and Lynyrd Skynyrd toured the United States together, in October 1977 they declined an invitation to travel with Skynyrd on the flight from Greenville, South Carolina to their next show in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. The plane crashed, killing Skynyrd’s Ronnie Van Zant, Steve and Cassie Gaines, road manager Dean Kilpatrick and both pilots.

“We’d seen their plane, which looked like Gaffa Tape Airlines,” said Agnew. McCafferty claimed that one of the pilots had attended the barbeque at the house of drummer Artimus Pyle before the classic line-up of Skynyrd boarded the aircraft. However, radio reports had claimed that Nazareth did board the flight, so when McCafferty telephoned home his wife Maryann wept tears of relief.

Unlike Purple, Skynyrd or GN’R, Nazareth neither attained nor particularly sought A-List celebrity, although without doubt they made a better-than-average career out of music, notching a run of hit singles that included Broken Down Angel, Bad Bad Boy, My White Bicycle, This Flight Tonight and May The Sunshine during the 70s, and recording a hefty catalogue that now includes 25 studio albums.

With guitarist Manny Charlton quitting in 1990, and co-founding drummer Darrell Sweet dying of a heart attack while on tour nine years later, as Nazareth’s first flush of stardom dimmed, Agnew and McCafferty gratefully accepted the status of being, in the bassist’s own words, a band that “sings for its supper”.

“We’ve been a rock band, we’ve been pop stars, and then we became dinosaurs,” Agnew said that evening 20 years ago at the Pitfirrane Hotel. “But live through the dinosaur period and you become a legend.”

With the band not having a new album or tour to promote, or even an anniversary to celebrate, we re-posted the Nazareth retrospective story in a fairly random fashion, but it rapidly began to draw readers, and its popularity continued to increase over the following weeks. It went on to become our most-viewed music story of 2023, and second-most overall. Which seems like a good enough reason for a catch-up with the Naz…

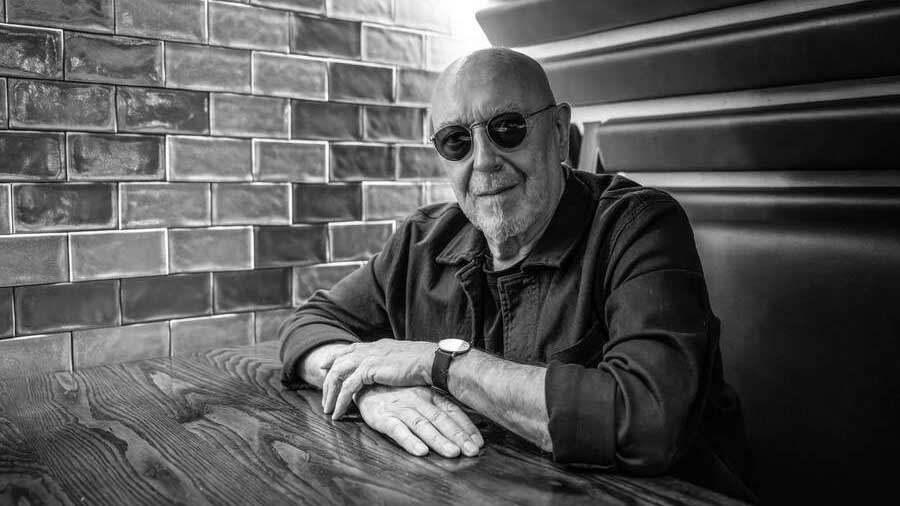

Twenty years on, it’s Pete Agnew alone that greets Classic Rock for an alcohol-free yet no less convivial lunch at the Hard Rock Café in London’s Leicester Square. A year after losing his oldest friend and bandmate McCafferty at the age of 76, the pain from that still lingers. The pair had stated many times before that they were like an old married couple. If one of them was late coming down from their room for a hotel breakfast, the other knew perfectly well what to order for them.

Dealing with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, which causes a shortness of breath, rendered singer McCafferty’s final few years in Nazareth difficult. He was a fiercely proud guy, and despite his well-publicised drinking and smoking, throughout his career only a handful of shows had to be cancelled, so the curtailing of a gig in Switzerland after just three songs waved a massive red flag.

McCafferty retired from the band on August 28, 2013, ending a 45-year run as frontman with the declaration: “If you can’t do the job, then you shouldn’t be there – Nazareth’s too big for that.” Agnew, the singer’s best mate for more than half a century, was “crushed”.

Respecting McCafferty’s departing wish that Nazareth continue without him would prove difficult, and Agnew admits that he very nearly gave up, especially after a doomed first attempt with Linton Osborne, a local singer, who he now admits was “a quick choice”.

“For a while I thought: ‘Oh well, at least we gave it a go’,” Agnew says. “Maybe this was the time to stop.” It was Ted McKenna, former drummer with the Sensational Alex Harvey Band, who suggested to Nazareth that they check out Carl Sentance, an Englishman who had sung with Persian Risk (the Welsh band who introduced future Motörhead guitarist Phil Campbell), Krokus and the solo bands of Black Sabbath bassist Geezer Butler and Deep Purple keyboard player Don Airey.

A few days prior to our conversation, Facebook ‘memories’ had reminded me of the first time I saw Nazareth with Sentance at the mic, at the Brooklyn Bowl in London eight years ago.“That was Carl’s third or fourth gig, right at the start of the ‘new band’,” Agnew says.

Oddly, the audience that night had seemed just as nervous as the band. Nobody wanted a second failure.

With a new guy there’s always anxiety, but this was a brand new singer, and we were in London, which makes things more pressurised still. What I remember most about that gig was the intro tape buggering up. In true Spinal Tap style, the tape rolled through twice and the audience stood around looking confused as it cut out and began playing for a third time. That doesn’t exactly bring a good feeling just as you’re about to walk on stage, but Carl dealt with the situation very well.

Yeah, he did. The ‘new boy’ strode out from the wings and demanded: “Kill that fucking tape, for god’s sake!” before adding: “We’re going to have a good time tonight, let’s kick some fucking ass.”

That’s the guy’s character. Carl is a very, very good frontman. When the new band plays somewhere for the first time, the reviews always say this is a guy that knows what he’s doing. He involves the audience and he’s energetic – I have to be careful not to get stepped on while he’s running about. He’s an old-school frontman and he fits in really well. Especially when you consider what enormous shoes he’s filling. Anyone coming after Dan had better be a first-class singer. Carl doesn’t sound like Dan – nobody could – but he’s a great fit with the band. We never had any thoughts that after Dan it could work. I had a lot of doubts. We got very lucky.

After that show at the Brooklyn Bowl, I suggested to you that Love Hurts, Dan’s signature power ballad (a song first popularised by the Everly Brothers back in the early 60s) should perhaps be retired from the set. You strongly disagreed.

What you’re saying is essentially true, though whenever I hear that song, regardless of the vocalist, in my head I still hear Dan singing it. But it would be impossible to drop Love Hurts. Without it there probably wouldn’t be a Nazareth. That song becoming a hit was what made the Hair Of The Dog album take off. It had come out in the UK [in 1975] and done nothing in six months, then the same thing happened in the States. But Jerry Moss [co-owner of A&M Records], God bless him, heard our version of the song recorded as a B-side and insisted it went onto the album.

Thank God that he did. It became such a big hit that Nazareth has lasted forever. Unfortunately, we’re not like Rod Stewart, who releases one song and it’s a hit all over the world. We’ll have a great big hit in South Africa, or another song of ours takes off in Russia or Brazil and does absolutely fuck all anywhere else. It’s hard to keep track of that, because if you don’t play the local favourite everybody wants their money back.

Not receiving a phone call from Dan, and not being able to call him, on July first last year must have been very tough.

That first time was very, very weird. It’s the time I really, really felt it. The first of July will always mean something to me. The Americans have the fourth of July, Nazareth has the first of July.

Does it soften the blow a little that you get to spend so much time with your son Lee, who came into Nazareth on drums after Darrell Sweet died?

It does. Lee has become a real driving force in the band. He writes these really rocking songs. All the guys in the band are writers, which brings us a lot of different styles.

It was genuinely shocking to learn that you’d quit drinking a decade ago.

It was quite an easy choice, actually: stop drinking or die. So I stopped.

It seems almost inconceivable. Nazareth were legendary drinkers.

[Laughs] Anyone who went out drinking with Dan and I would agree. Absolutely. But in the end it caught up with me. Every bodily function started to close down. I went into hospital, and for a while it looked like I might not be coming out again. Since then I haven’t touched a drop. To tell you the truth, I wasn’t an alcoholic, I just loved a bevvy. I like beer. I didn’t even like whisky. I don’t miss the buzz so much, just the taste.

How were the first gigs you played without having a drink?

They were unusual. I never used to be drunk on stage but I always had a buzz on. Playing completely straight was weird. I had to ask: “Was that alright?” Because it didn’t really feel like that to me. But it passed, and it’s lovely to wake up in the morning and be able to remember why you got punched in the head the night before. There were times when I never had a clue.

Now that the dust has settled on the line-up changes, in your heart of hearts does it still feel to you like Nazareth?

[After a moment’s pause] That’s a hard one to answer. On some nights I realise that not only am I the last of the originals still in the band, I’m also the last one of us left alive. Manny [Charlton] had been out of the band longer than he was ever in it, so Jimmy [Murrison, who joined in 1994] is our guitarist. Those [very early] times are just memories for me. Dan and I continued Nazareth and it felt completely natural.

Obviously, when Dan had to leave, that’s when everything changed. Dan’s voice was Nazareth. He was what separated us from all those other bands – especially the heavy metal bands whose singers to me are interchangeable. As soon as Dan opened his mouth, that’s Nazareth. Without Dan it no longer felt like Nazareth, though it does again now.

How long did it take to reach that point?

I needed a few years. Jimmy and Lee have been there so long now, which helped to make things comfortable. But this was my best pal, and it was quite a wrench. I’d say it took three or four years. It felt so strange. I wouldn’t say it was like being in a covers band, but it felt a wee bit of a cheat. I had looked at all those other bands with just one original member, and now I was one of them. It was like: “Ah yes, fair enough, as long as the people still accept us.”

We were still getting good crowds, in some cases bigger ones than we did before, because the reputation of this band [fronted by Sentance] is really, really good. That acceptance helped me to come to terms with the situation. I’ve realised that we are adding something to the Nazareth thing, not taking away from it.

Nazareth now play these amazing festivals in mainland Europe, attended by a younger type of fan who probably regards you as a new band. That must seem very odd.

A lot of people are not only seeing us for the first time, they weren’t even alive for the original band – people that don’t know or care who played on which album, they just know the name and enjoy hearing the songs. And you know what? If they think it’s Nazareth and I think it’s Nazareth… it’s Nazareth.

And yet here in the UK we rarely see Nazareth play any more. There was a pretty big push to regain some of the lost ground at the start of the current millennium, but it now feels like that’s been relinquished.

It’s very difficult for a band like us to do a tour and make it work financially. Our very good friends Big Country do nothing but play here [in the UK], they’re out every weekend. Because they’re regulars they have retained their fan base. There’s no point in playing one British gig every blue moon. We’ve done twenty gigs in Germany in the last two months, but when we try to play here we tend to get: “‘Oh, those guys? Are they still going?” It’s always been like that for Nazareth. For twenty years we scarcely played here at all. I’d love to rectify that, but it’s the financials. And starting out again in clubs? No. I did all that stuff a long time ago.

So if a band like Status Quo happen to read this…

Ah, you see, that’s another problem. Not a lot of bands [of our own vintage] will let us open up for them. Now and again we get a gig with one of the biggies, and then we don’t hear from them again for three or four years. I won’t say any more than that.

Nazareth with Carl Sentance have released two albums. The sound became a little punkier with Tattooed On My Brain and Surviving The Law (2018 and 2022).

Probably it has. It’s harder-edged than what we were doing in the eighties. That’s what keeps things interesting. I think the fans quite like that diversity.

Why is it still important for you and Nazareth to keep on making new music?

It’s about credibility, mainly. People must know that you’re still creative. We’ll never stop writing. The problem is getting to play the songs live. Even if an album gets great reviews, it’s tough to include more than a couple of new ones in the set. Not too long ago we played with Deep Purple, and people said: “That set, you could have played it twenty or thirty years ago.” To which I replied: “Wait till you see these guys [Purple].”

Nazareth’s road tales of turning down the offer to travel on Skynyrd’s plane, your association with Guns N’ Roses, and even you lending fifteen pounds to a broke Robert Plant for petrol so that the Band Of Joy could get to a gig in Scotland, are legendary. Are new chapters still being written?

Aye. They’re a little less crazy than they were before, but life is never boring. For a while I started jotting them down [as an autobiography], and then I started to realise I’d probably have to wait till I’m dead to publish it. Otherwise I would start getting punches in the head.

Did Robert Plant ever pay back the fifteen quid you lent him?

Did he fuck! I’ve written that off. Maybe I should charge him interest.

If, as you said, Nazareth have been pop stars, rock stars, dinosaurs and legends, where do the band stand at this point in their career?

I would say we’ve become legendary legends. Nah, I’m kidding. What I’m most proud of is that we tried to put across a number of different types of rock music. A couple of times – more than a couple of times – it didn’t work, but on the whole we were fairly successful at it. We always tried to make each record different than the one before. We’ve made twenty-five albums, and I can put my hand on my heart and say that I’ve liked most of them.

You’re now seventy-seven. Will you ever retire?

I can’t even think about not being in the band. I can be off the road for a month and quite enjoy it, but after five weeks I need a gig. If the time comes when I start talking about scones and cups of coffee, please shoot me. Y’know, that’s when I start drinking again [laughs]. But here’s the thing. We do these European festivals with bands of a certain vintage – I’m talking about Sweet, Uriah Heep and Wishbone Ash; I call them ‘the usual suspects’. When it was time to leave, I always used to say: “See you next year.” But now I find myself saying: “I might see you again.” There’s a big difference.

Nazareth have European dates lined up throughout the summer. They play a rare UK show at the Love Live Festival in Blackpool on March 2, 2025.