Neil Peart’s dressing room is bordello red. across the corridor from the one Geddy Lee and Alex Lifeson share, Neil’s is filled with a black-and-white drum kit that dominates the space. Possibly not to be outdone, Geddy and Alex keep a well-stocked bar in theirs.

Neil’s smoking; he smokes a lot. He grins a lot, too. This is not the stone-faced drummer lost at the back somewhere behind racks of equipment, sparkling aluminium stands and sets of cymbals grouped around him like satellites around the Earth. That’s when he’s concentrating, his face set hard against the ever-shifting beams of light making great washes of colour across the stage.

Back here at the Starwood Ampitheater, before Peart practices for over 30 minutes just so that he can go on stage to rehearse a three-hour set (including a drum solo that makes your arms ache just watching it), he’s relaxed, excited, up. A few drum magazine interviews aside, he hasn’t really spoken to the press since Rush toured their Test For Echo album.

Peart’s daughter died in a car accident in the summer of ’97, then less than a year later his wife succumbed to cancer and also died. Rush as an entity pulled down the shutters and turned off the light. Time passed. Eventually, Peart moved out to California. And then, in September 2000, he married again. One two-week period aside – in which he played every day – he didn’t pick up his drumsticks for four years.

Peart had lost his spirit – that was how Geddy Lee had put it to me when I’d interviewed him and Alex around the time of their then comeback album, Vapor Trails. That album belied the fact; it was ferocious and dazzling, and prompted you to remember why you’d fallen so heavily for Rush the first time around. It’s themes hinted at heartache; its imagery aspired to redemption.

The tour that followed it, including a string of sold-out stadium shows in South America – the band’s first on that continent – proved their vitality, not least to themselves.

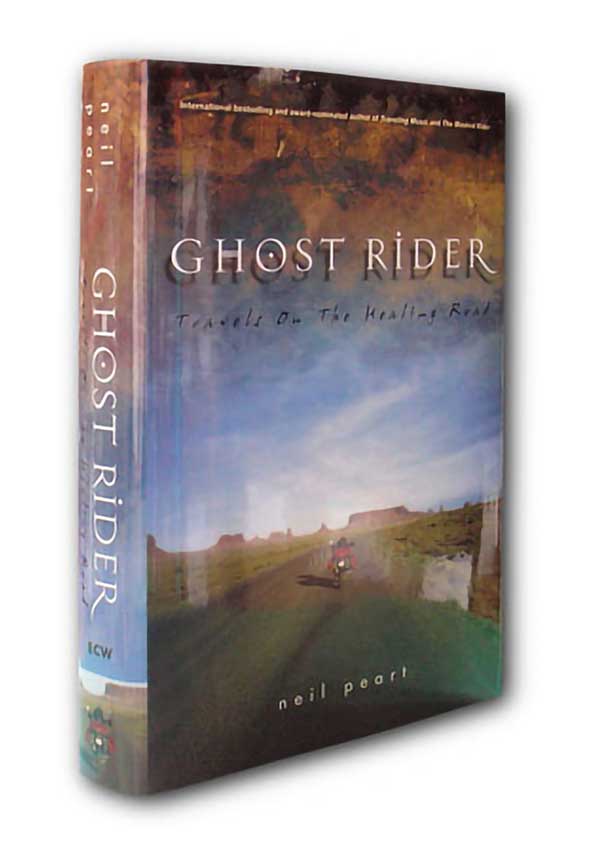

I hadn’t been sure what to make of Neil Peart. Press cuttings suggested economy and wit; his books, especially the excellent Ghost Rider (which charted his tragedies and the journey he took to come to terms with his loss), a talented, self-effacing voice.

Live, however, his deeply furrowed brow and permanently buttoned-up lip put me in mind of a former headmaster who bore a grudge against me, albeit one sporting what looked like a deflated fez.

In interview, there are brief moments of introspection, admittedly, but only when Peart is attempting to fully articulate answers to certain questions (none of which he ducks, by the way). Otherwise, it’s long ribbons of cigarette smoke and lots of laughter – and no sign of that hat.

The three of you seemed to have a lot of fun making your recently released Feedback covers album. Oh yeah, you know, the songs that we first learned chords and drum parts to in the first bands we played in that influenced us when we were fourteen or fifteen… how couldn’t you? It was great, and so much fun to go in and not to write the songs and not worry about the lyrics and construction.

Normally in our cycle of things – album, tour, time off – we should have been making an album right now, but we weren’t going to miss our anniversary and not commemorate it in some vital way, so we came up with that. And we recorded them so fast. We were whipping off a couple of songs a day, easily.

How did you go about choosing the live set-list to celebrate Rush’s 30th anniversary?

That was big. We started at the beginning, you know. We do Finding My Way at the beginning, we do the R30 Overture, songs we wanted to play, but not in their entirety. We always wanted to bring back things like Mystic Rhythms, so we just added a wish list. And, of course, we had way too many.

Closer To The Heart got retired because we got sick of it, but our other songs are pretty difficult to play, so you don’t get sick of them every night. They’re not songs you can easily cover, either. There was that British band Catherine Wheel, who did Spirit Of Radio, and they did a really good version, and I heard an interview with the guy going: ‘The parts we left out were the ones we can’t play…’ [laughs]

Your personal touring schedule is different to the rest of the band’s, isn’t it?

I leave straight off the stage and sleep on my own bus in a truck stop or somewhere. Then I load the bikes off in the morning and, if it’s a day off, I ride somewhere in the mountains or wherever. Or I get up in the morning and ride into the show and just have a world apart as much as I can. I started doing that around Test For Echo.

I used to bicycle before that. I always had a bicycle on the bus with me, and at least then I could get the bus to drop me off and I could get away. But the motorbike is, like, complete freedom.

On the Rush In Rio DVD you all look pretty beat up by the demands of a long tour. How will you cope with the 57 dates you’re doing this time?

As long as I can play well, I don’t care about injuries. The Test For Echo tour I had an elbow brace on my arm at the end of that, but I can still play well. I don’t care if it hurts, as long as I can get in the default position, as it were. It’s when you can’t play that it gets depressing.

I know that Geddy didn’t feel like he was getting to play fully during tours for albums like Hold Your Fire.

With the late eighties there was so much technology available to us that we couldn’t resist. We have this rule that we have to do everything ourselves; there’s no tapes. If I can hit a trigger for a keyboard sound, I will, and Alex and Geddy were dancing all over to cover sounds.

That’s something now that when we put a set together we’re very conscious of. Geddy’s like: ‘I don’t want to be up on the keyboards all the time.’ So we separate them out. And that’s the joy of our older material and the Feedback stuff, we just play.

On a happier touring note, you got to play 2112 in its entirety for the first time on the Test For Echo tour.

When it came out in seventy-six we were still supporting or doing an hour-long headline set, so we did an abridged version even at the very beginning. And even when we started headlining small theatres and such we still kept it abridged. So by Test… we thought it was time.

And playing it you do find yourself grinning at the past in a way, being in that young man’s headspace. You tend to be harsher on your old material than you need to be, and then it’s: that’s not so bad at all. And for some of them you go, wow, that’s good. So they make it back into the set.

After the disappointing reaction to the Caress Of Steel album, you almost didn’t get to make 2112.

Caress… didn’t actually do any worse than the albums before it, they all did about a hundred thousand copies in the US. But if our record company hadn’t been in such turmoil, I don’t think we would have kept our recording contract with three records only selling that many copies. That tour, too, was so stagnant. We called it the ‘Down The Tubes Tour’, we joked about it among ourselves.

By the end of that year we were unable to pay our crew’s salaries – or our own. Things were dire, and we were getting a lot of pressure because that was in the summer of seventy-five, and by the end of that year we were in the proverbial dire straits.

Polygram had written us off before 2112 had come – we’d seen their financial predictions for seventy-six and we weren’t even on it! And then it was all, they don’t want a concept album… It became a do or die situation. Fortunately, things just turned around slowly; we were getting better gigs and the records started selling better.

We became respectable or something in the industry and then we never got intrusion or leverage from the record company. It was the turning point, true justice!

Do you think Caress… deserved the criticism?

It was weird. We loved it so much when we made it. We were flushed with the excitement – it was our second album together as the three of us – and we knew we were going all over the shop stylistically. Then when it didn’t do well we were kind of stung about it for a little while.

No, I don’t think it really stands up. It is all over the shop, and it is experimental, and it’s only real virtue is its sincerity, but at least that’s something. We see our bridges, though; we wouldn’t have made 2112 if we hadn’t made that. I can trace the roots of all our material from our previous experiments. Sometimes the experiment didn’t work but the lesson is learned and it becomes a template for the future.

It’s about nineteen-eighty that I really start to like our music like a fan. Before that there’s stuff I like in an affectionate way, because we were brave, but as far as achievement I really think we started to bring it together a bit with Permanent Waves…, but particularly Moving Pictures and from then on.

Caress… was also your first album that had cover art designed by Hugh Syme.

He was playing for the Ian Thomas Band when I met him, and they had the same management company as us. They showed me some artwork he’d done for Ian Thomas and I really liked it. I had collaborated on [preceding album] Fly By Night with the art director at Mercury Records, so I was kind of the spokesperson for our graphic arts department. I still am.

Hugh and I struck up such an artistic collaboration that he and I can be on the phone and bounce ideas off each other, and know how it’s going to look before it’s done. He does my book covers, my videos, the instructional DVD… he’s my graphics art guy.

But you were foiled in your attempt to get cartoon cat Snagglepuss on the cover of Exit Stage Left.

We only wanted the tail for Exit…. We wanted to have the rest of the cover and just his tail exiting stage left. But even the tail was beyond the pale, moneywise.

We went through a similar thing for Rio when we wanted to use The Girl From Ipanema, and they wanted something like forty thousand dollars just to use it. And our publishing guys said: ‘Do you want to reconsider and use something else?’ And we didn’t, because it’s a highlight of the show, Alex introduces us and I play a little and then Geddy goes into …Ipanema, so we had to have it whatever it cost. There are amazing things like that that you run in to all the time.

Going back to the 70s, you’ve described that decade as ‘a dark tunnel’, while one of the tours you did in that period became the Drive Until You Die tour. Were things really that bad?

We were playing so much, we were doing nine or ten one-nighters in a row, and we were driving ourselves, don’t forget – we were doing three-hundred-mile shifts each across Texas. It was play, drive, play drive.

And if you did get a day off there was no recreation about it, you would just lie in a dark room and be stunned, watching cartoons because you were so drained. It was soul-destroying. It takes so much out of you. It was an important turning point, because we hadn’t learned to say no yet; we were these kids from the suburbs. So that’s where we were caught in the mid-seventies. Then we’d go off the road and straight into the studio.

We did four albums in the first two years and then one every year afterward, and we were playing so much. Then, we’d go in with a few acoustic guitars, some words sketched out, and we’d blitz, just work and as hard and as long as we could. We’ll never do that again. We had to learn that we can only do so much. It was impossible to hold any kind of relationship together at the time, let alone between us three.

You said that making Hemispheres has left you with a few scars, some which are still visible. What did you mean by that?

We were just coming out of a long period of work, and I think we’d ended our tour in Britain. We went straight off to Wales to record an album with nothing written and just worked ourselves into the ground. The job gets done and doesn’t suffer for it, but you do. Whatever it takes, it was always the same with us, all those years.

The shows didn’t suffer, they got better; we built our legend as a live band – and what a great legend to have. But that record took so much out of us that stress suddenly became a factor and we realised that we had to made a decision about how we were going to work in the future.

I think it was a hard lesson learned. I remember that at the end of Hemispheres we said we were never making a record that way again, that part was over. Permanent Waves was a step, we were stepping out of the longer formats to a certain degree, especially with Spirit Of Radio and Freewill; we were learning to be more concise. A lot of lessons were learned at that time. We stepped back from it.

Tell me a little bit about Canadian author Lesley Choice, who helped you get your first book published.

I loved his writing, and I wrote to him, just a fan letter, and he wrote back and said: ‘You write well. Ever thought about writing a book?’ And I was like: ‘Who, me?’ I’d written about eight books by then, but had just published fifty copies for friends. That was a luxury I had that I never had in music; I didn’t have to grow up in public. I would write things with way too many adjectives, stream-of-consciousness stuff, and it was okay to do that.

By the time I’d got to publishing The Masked Rider I’d written six to eight books by then and put them aside. And everything fits in travel writing – it’s like a backpack – and that’s why I gravitated to it.

And you wrote Ghost Rider during the sessions for Vapor Trails?

I was writing it all the way through. We were in the studio for a year, working quite leisurely at the songwriting, and while I was working on the lyrics I’d always try and write a page a day. By the time we were mixing I was in the revisions of Ghost Rider.

So I was in the studio lounge, the guys are back and forth, there’s a mixing desk right there behind the window, the TV’s on, people are in and out, and I’m trying to revise. It made me realise that it started back in the seventies – my constantly reading to escape a crowded dressing room. I learned to focus that way.

Now I have my own little room and my own bus I have privacy, but I couldn’t get it then and the only way to get some was to hide behind something, and the book became that.

You’ve always said that your lyrics were informed by prose more than by poetry.

I always read prose, though I have gone back now and learned to appreciate poetry a bit more. But they [lyrics] are always written as song lyrics, not as precious poetry. And my stylistic influences were always prose writers who created moods, and those were the people I read.

I’ve developed… you learn the skills, as you do in music. It’s a craft. And a very hard one to put in simple words when you have a complex reason to life or a feeling within yourself. The more skill you have at that, the more satisfying it becomes.

A song is… what, a hundred words? That’s very little to get right what you want. I love bringing the words to Geddy and Alex. I sense their belief even if they want to change a part here or there, because I know they’re going to like it. And that excites me.

Talking of people you admire, you’ve praised TS Eliot’s ability to ‘flood the image’.

It made me realise you could enjoy something even if you didn’t exactly understand it. At first it can be intimidating; it was like when I was a teenager and I saw my first Fellini movie. I was like: ‘What?!’ But those images stayed with me, and there would always be a line in TS Eliot that would come home to you and you would resonate with it.

As a lyric writer, you’re trying to trigger an emotional response, and because your words are being sung as well that gives you so much more ammunition. When I first hear a song being sung I can tell what resonates with Geddy and works in his heart. It’s music, after all, not science.

And you avoid overtly confessional lyrics?

I like to find the universal aspect of a song. A lot of the songs on Vapor Trails are an example of that. They’re obviously very personal, but I try to find a way to transcend them. This is what memories are like for everybody – those vapor trails in the sky. It’s not just me, they fade.

The nature of memory I explored in a few of those songs – even Ghost Rider [the song] is about my travels – but I tried to find universal emotional touchstones that other people could discover in their lives. Maybe people will find their own resonance in a song.

I like to weave imagery that has a basis in me, so that it’s heartfelt, but that is also obscure enough so the listener can find something within it for them. It’s like a wind chime; the wind blows through it and makes it sing.

The lyrics to one of your songs, Limelight, seem a pretty straightforward distillation of the problems of fame.

We were dealing with that at the time, especially me as I’m kind of shy. That song was trying to deal with those themes and express them in some way. I realise now that it’s inexpressible. When someone comes up to me and goes: ‘Neil!’ And you don’t know them.... If anyone in normal life gets recognised by a stranger then it’s just weird. I never set out to be famous, I set out to be good.

What can you remember of the first show in Hartford, Connecticut, when the band kicked off on the Vapor Trails tour? It must have been a massive step.

It was so emotional for the three of us, because they [Geddy and Alex] had been so strong for me and so supportive through my troubles. We hadn’t played in front of an audience for so long. I said to Ray [Danniels], our manager, at the end of that show, that it would have been a shame if this had never happened again.

Because of course a few years previously I was convinced that it was never going to happen again. And in that show we just looked at each other and it was just so very powerful and emotional.

You talked earlier about transporting yourself to shows, and you’ve said that since getting on a bicycle you’ve developed a whole new affection for America. Meaning?

For twenty years all I saw were arenas and hotels and the tour bus. Songs like Middletown Dreams could never have happened if I hadn’t gone out on my bicycle and realised there’s a Middletown in every State. I met and continue to meet people on an informal basis like that, in a hotel or a gas station or whatever.

These interludes with real Americans outside of any other context, well… you get talking to somebody and think, this is the real America, you know. There are a lot of experiences and images that I could never have got without going out there and finding them.

I travelled here on my motorcycle because I want to write a book about this tour and I thought there’s no better way to start the book than with a road trip. So I rode the bike from LA to here, to Nashville. It took three days, two thousand miles, it was a slog, but I wanted that immersion in America and the American road, especially to begin the tour, because to me there couldn’t be a better set up to build the tour from.

You’re finally coming back to Europe. It must be a sort of homecoming for you, having lived in London in your teens.

I was in London for eighteen months. I was eighteen, so it was such an important time for me. I’d never been away from home before. I played with some bands, and became so disillusioned with the music business that when I came back from there I was prepared to work with my dad for a living and play music part-time.

I worked in the farm equipment business and I accepted the reality. I wasn’t going to sacrifice my ideals musically, I made the choice that I would work for a living, then I’d play the music I loved at night. Then Rush came along the following year. That was nineteen seventy-four – thirty years ago.

This feature was originally published in Classic Rock 71, in August 2004.