"Neil would do a full hour of unrelenting drumming before he went on stage to play for another three": A personal tribute to Neil Peart

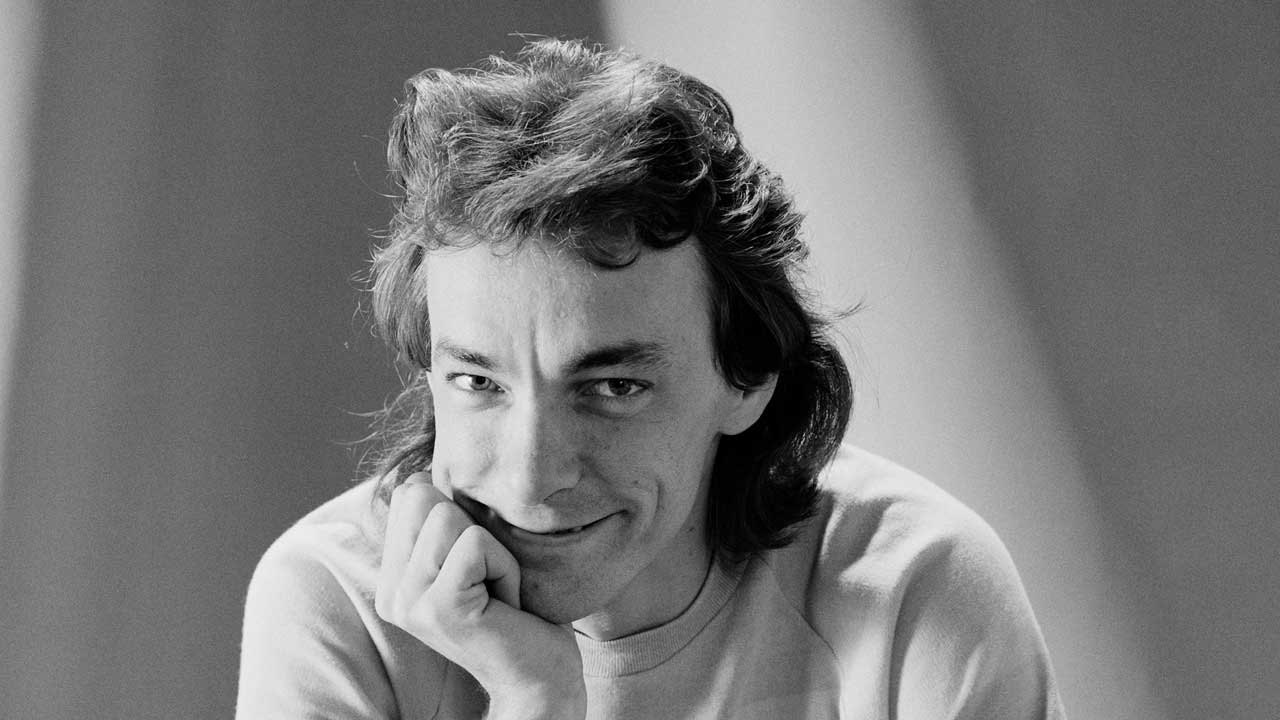

A personal look back at the music, life and times of Neil Peart, the Rush drummer/lyricist and cornerstone who died on January 7, 2020

We were sitting in Topanga Canyon, California, Neil Peart and I, at the Inn Of The Seventh Ray, his choice. We had already moved seats once, because a nearby babbling brook was overwhelming my tape recorder. But if it wasn’t the small stream of water coming down the nearby hill that stopped us, then it was the extraordinary mixture of pan pipes and soothing new-age music coming from the venue’s speakers.

At one point a unique interpretation of Greensleeves made us look up sharply from our raw soup. Soup, the menu told us, that had been ‘created through the vibrations of each day’. I was quick to point out how much that sounded like one of his lyrics, and that that was clearly why he’d chosen this place.

It was spring 2012. Spirits were high, and I was there to interview Neil for Clockwork Angels, Rush’s final album. This seemed like an impossible idea at the time, given its energy and lustre. The band were in town to add the final touches to the record’s mix at Jim Henson Studios. It was Neil’s eighteenth album alongside bassist/singer Geddy Lee and guitarist Alex Lifeson, who he’d joined in Rush following the departure of John Rutsey, arriving in time for second album Fly By Night.

Unusually for a drummer, Peart also wrote Rush’s lyrics. “I am a fan of Neil’s, and I love being a collaborator with him, because he is so objective and easy to work with,” said Geddy. “He’ll even allow me to suggest lyrics – a word that might work well – and he’ll accept it or he’ll come up with a better one. He’s really a pleasure to work with. With Neil there are no hissy fits, ever.”

Neil and I sat for hours that afternoon on the restaurant’s patio, in an idyllic corner of old California that had been attracting the well-heeled rock star for years. Among other things, we talked about time passed, the shape of things, not least because Neil had turned 60 the previous September. I asked him how he felt about that.

“I feel proud as hell,” he said, and he seemed it too. “I’m at the height of my powers in one sense, but also I can’t help feeling the empathy for someone like Keith Moon. He never got to be fifty-nine. Dennis Wilson neither. John Bonham… These are cautionary tales in a sense, but they break my heart: they had children, they had loved ones, they never got there, they never got this – this kind of career.”

Neil was bold and brilliant and a lot of fun (an interview with him was never dull, but on that day he had been especially avuncular, open to talking about anything). We walked out to admire his latest Aston Martin, one of his collection – a purple shell under which was a terrifying-sounding engine, in a car that looked capable of space flight. We promised to meet at the studio later and he dropped down the hill and out of sight at an alarming speed, lost almost instantly to the traffic. He was brimming with life.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Neil Peart was born on his family’s farm near Hagersville in Ontario, Canada on September 12, 1952. A few years later the family moved to St. Catherines, a middle-class Canadian suburban town 70 miles from Toronto. In 1994, Peart wrote a lovely, evocative piece for local paper The Standard on his formative years there. It wasn’t only his lyrics that sang, his prose came right off the page too. He once told me he’d struggled writing fiction, but the idea of travel writing and memoirs always moved him more. “What I want to do is look around and try to put it into words, how you try to portray those memories for other people, that’s plenty.”

I urge you to read The Standard piece, not only to remind anyone of the pain that adolescence can hold, even for a rock star-in-waiting, but also for the flashes of colour that came from Peart’s pen, moments that sound like a Rush song we somehow might have missed. His musings on dinner at the Niagara Frontier House read: “Red-upholstered booths, lights glinting on wood, Formica, and stainless steel, the Hamilton Beach milkshake machine, the tray of pies on the counter, and the chrome jukebox beside each booth, with those metal pages you could flip through to read the songs.”

And later, something a little more honest from a kid who felt things a little more keenly than others, who permed his hair and wore a purple cape on the bus ride across town. “So, what was it like to grow up in St. Catharines in those days? Well, as some of these stories will attest, it was a wonderful place to be a boy. I have since written that mood into songs like The Analog Kid and Lakeside Park. For a teenager, however, especially a rebellious and self-consciously different teenager, St. Catharines in those days was not so nice. I have written about that mood in songs like Subdivisions."

It was writing Subdivsions, for Rush’s 1982 album Signals, that took Neil further away from the fantastical and towards the more personal in his lyrics. As he told Rolling Stone: “A lot of the early fantasy stuff was just for fun, because I didn’t believe yet that I could put something real into a song. Subdivisions happened to be an anthem for a lot of people who grew up under those circumstances, and from then on I realised what I most wanted to put in a song was human experience.”

It’s been seven fleeting years since our lunch in Topanga. Since then, Rush wrapped up their final album and then played some of the best live shows I’ve ever seen them play. Not least that final gig at the LA Forum on August 1, 2015, where Neil crossed to the front of the stage at the end – he was usually in the wings and on the way to his own bus at that point in the evening – and embraced a startled Geddy and Alex and bade us and them farewell one final time.

Gone then and forever now, we were lucky to even have that final era of Rush. Geddy still calls it his favourite time with the band.

Neil had already left Rush once. He told his bandmates to consider him retired after the death of his 19-year-old daughter, Selena, in a single-car accident in August 1997, as she drove from her parents’ home back to university in Toronto.

Subsequently, Neil and his partner, Jackie Taylor, spent time in London, perhaps trying to escape the mental anguish by putting physical miles between themselves and that moment. While in counselling for their grief, Jackie complained of back pain. Only five months after their daughter’s death, she was diagnosed with terminal cancer. She succumbed quickly.

Neil disappeared. He grabbed his beloved BMW motorbike and rode toward the fast-fading sun. He sent occasional, cryptic postcards to Geddy and Alex from far-flung corners of the USA, just to let them know he was still living somehow, still moving forward.

We talked about that period later, after he’d published that story in the best of his books, Ghost Rider: Travels On The Healing Road, and how he said that his motorbike had saved him.

“The bike did save me, absolutely,” he confided. “I had nothing else to do. There was nothing else I could do. The telling episode was on the first day out. I’m in terrible weather, with logging trucks flashing me, and I’m miserable anyway and I’m lacking fortitude of any kind. And I thought: ‘I’ve got to turn around, I don’t want to do this.’ And then the other voice went: ‘Then what?’ Because I had nothing else. And the stupid things people say to you at a time like that… ‘Oh, at least you have your music.’ Fuck, what?! It’s so maddening. I just wish people wouldn’t say it, it’s so stupid. You don’t have anything. But it, the bike and the journey I took, absolutely did save me. But so did the booze and drugs!”

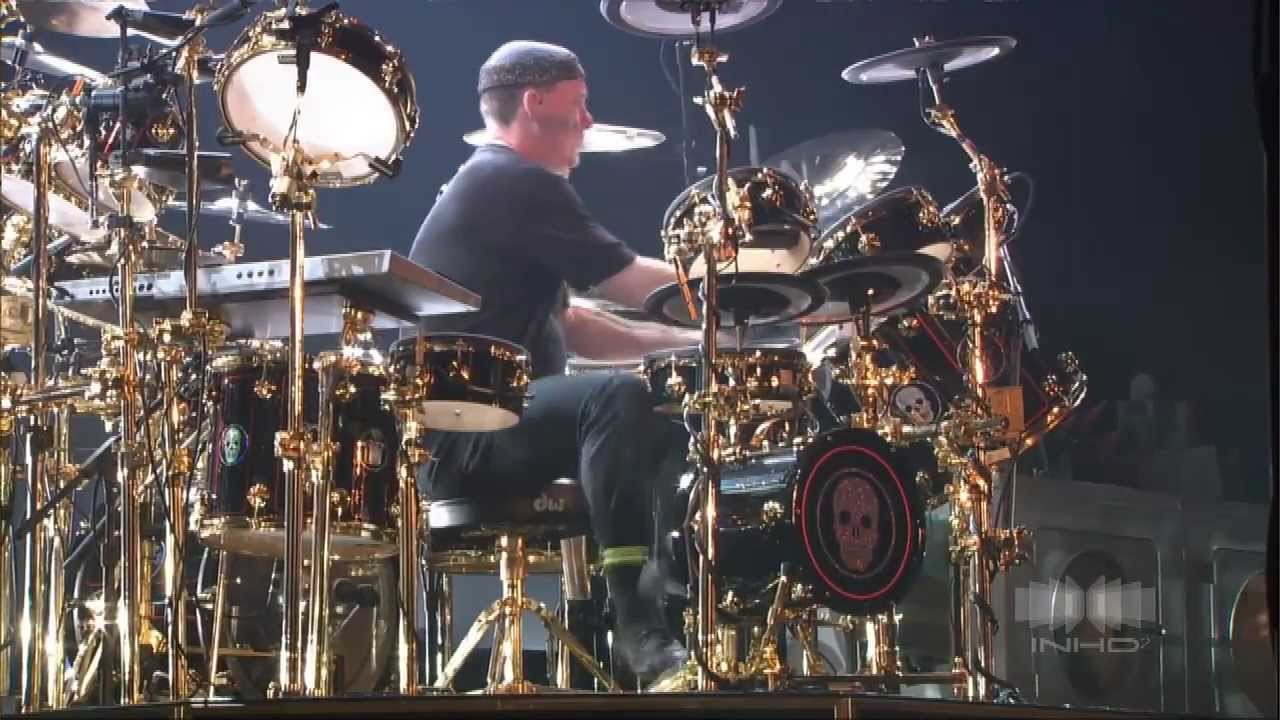

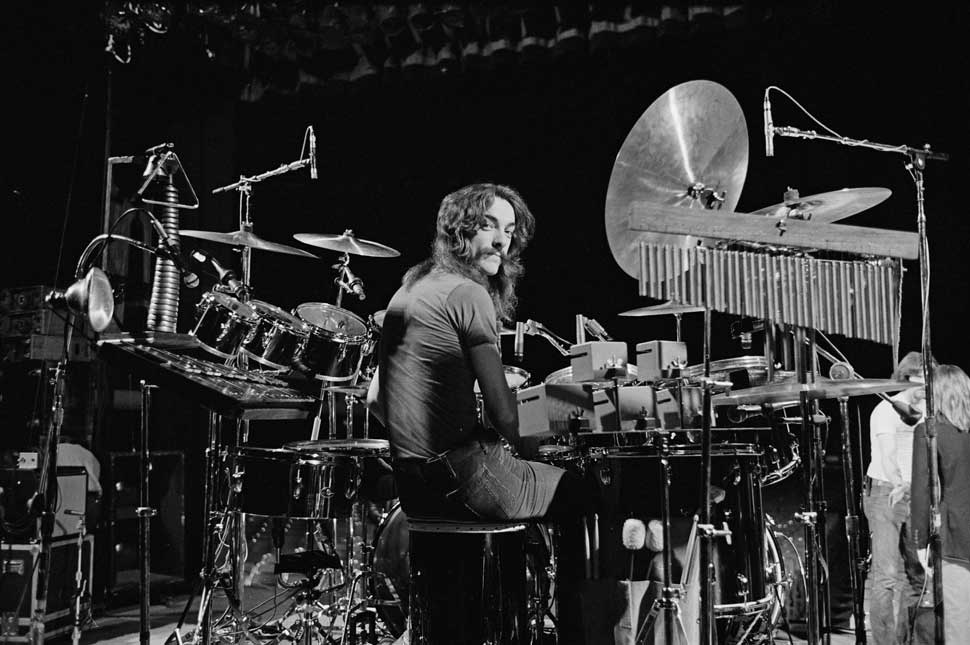

He meant it about the music too. Neil had played his drums every day since he was teenager, ever since he got his first kit for his fourteenth birthday, and only took a day off at Christmas. But after his twin tragedies he didn’t touch his drums for years. This from the man who, as Geddy would often say, “plays to play”. It was true, too. Neil would do a full hour of unrelenting drumming before he went on stage to play for another three, including a drum solo that actually dragged people in from the bar, not propelled them towards it.

Geddy and Alex would occasionally watch him from the wings, still stunned as they had been the day they first met him when he’d auditioned for the band. Then, Geddy thought Neil was a goof, Alex wasn’t sure what to make of him. But they both remember exchanging glances as soon as he began to race around his drums, silent, and they telegraphed signals between them that this was their guy.

When Neil finally came back to Rush in 2001, for the sessions that would become Vapor Trails, the band would work through the day, Geddy heading home as night fell while Alex, one of life’s natural night owls, would sit up with Neil.

“And we’d just play,” Alex remembered, “anything to help get his chops back up, just jam into the night.”

The sunlight coming in through the cab window is so strong it’s bleaching the California sky from blue to milky white. I’d landed just a few hours earlier and was heading to Jim Henson Studios. There, a smiling Kermit The Frog is set atop both posts of the iron gates. The studio is filled with history. Charlie Chaplin owned it for years, and forged his legend there. His footprints are still in the concrete path at the back of the outer buildings. The Muppets and ‘The Tramp’ all in one space. No wonder Rush were excited about mixing Clockwork Angels there.

“Did you see the footprints yet?” asked Neil, almost before I’d sat down. He was one of the first people to greet me in that labyrinth of corridors, soundproof doors and cavernous studio space. He was courteous and warm, holding a bottle of 12-year-old Macallan Scotch as a welcoming gift. He sourced tumblers too (and then Alex drank half of it, but that’s another story for another time), and in a small side studio we sat and listened to some of the fades and mixes of what would be their last album.

Neil and Geddy closed their eyes to fully feel the music as it disappeared to a whisper. Then Neil, Alex and I stood, as Geddy stepped into the next room and the vocal booth with producer Nick Raskulinecz to readdress the final parts of the vocal for The Garden. “Too much vibrato, try that again,” Raskulinecz said as Geddy was put through his paces.

They played me a few of the finished songs hrough the giant speakers in the main room and goofed around, the odd awkward smile as their beautiful music fell towards us, still strangely abashed by their accomplishments together after all these years.

The band liked Nick greatly, not least Neil, who had spent his career mapping out every drum part before he played it in the studio. On their previous album, Snakes & Arrows, Nick had pushed for Neil to play and feel more – groove and thunder, enjoy improvisation… He’d stand in front of Neil with a baton, keeping time, his arms acting as a human metronome, while Peart raged. I watched it through the glass once, me and Ged entranced by Neil’s new-found freedom, his freewheeling joy as he moved from drum to drum, his arms seemingly totally independent from what his feet were doing.

Later, as we stood in the studio car park waiting to head for dinner – Neil was planning on staying there a little longer to go over the record – he showed me his silver Aston Martin, the model that James Bond drove in Goldfinger (the purple spaceship one would be his ride the following day). It practically glowed in the sunshine, a low, sleek, omnipresent feat of engineering and hubris. I wanted to embrace it. Instead I asked him about working with Nick.

“He goofs around, but the enthusiasm and the energy is fantastic,” Neil said. “The first time we worked, he’d ask me to play something, and would mimic it and sing the parts, and it would be so over-the-top, just extraordinary, I’d be ashamed to throw a fill like that in myself. But I’d be like, ‘okay’, and then I’d pull it off and he’d be: ‘That’s great!’ It’s like the Caravan drum fill that I laid out. We went back into the booth to listen, and Ged looked over his glasses at me and said: ‘Oh, he wants to make you famous.’

“This time, it was more immediate. He was in the room with me, not listening to playbacks. He was right there, so that every time we stopped we’d be conversing over the parts. He was playing along with me. I didn’t have to learn the arrangements. He’s a generation younger than us, too, and that’s kind of an important touchstone. We did Snakes & Arrows with him and wanted him back, and he wanted to be back. He’s the perfect catalyst, that’s the word. He’s more than a collaborator.”

And then, while he was still in this happy reverie, Neil started talking about my first novel, Cross Country Murder Song. I knew he’d read it and I knew he’d enjoyed it – there had been an email that had almost made me faint with delirium and made the teenage Rush fan in me hyperventilate – but now this: “I read it again. It’s better the second time.” I looked at him like he’d just grown wings and had begun to levitate. “I took it on my last trip on my motorbike. It’s a road trip, so it was perfect to read while I was on the road,” he said.

I think he might have clapped me on the back as he told me we’d be heading to Topanga Canyon in the next few days for a more formal interview (which was anything but). Geddy was calling me to our car to go for dinner, and Neil walked away with a cheery wave.

I suppose I’m telling you all this to try to explain the happiness and energy that came off Rush (and Neil in particular) in waves on that trip. After so many years of them being together, Clockwork Angels was one of the best records the trio had ever made, and the future looked brighter still. Fast forward to early spring 2015, and I’m talking to Neil via Skype about his latest travelogue, Far And Near: On Days Like These and the impending R40 tour. For the first time in a long time, doubt was starting to catch in his voice. Having lost one family, it was clear he was going to embrace the time he had with his family now.

“People say: ‘Are you excited to be going on tour,’” he said. “Should I be excited about leaving my family? No. And no one should. It’s as simple as that. I pour my entire energy and enthusiasm into it, but, of course, I’m of two minds about the whole idea. Olivia [his daughter] is five now and I’ve been doing this for forty years. I know how to compartmentalise everything, and I can stand missing her, but I can’t stand her missing me. It’s painful and impossible to understand for her, and you feel guilty about it, of course. I’m the one causing her pain.”

Neil Peart never knew how much he touched my life, and I’m not sure he would have been comfortable with knowing. He was a goof, supremely talented, kind, open, and could catch a drumstick even if it had dropped from the sky. His words spurred me on to be a writer, his music to go on even when I didn’t want to and, along with his two incredible bandmates, reminded me that not all rock stars are self-serving morons.

So I’ll hold this moment in time and think of that long lunch in the Californian hills, being backstage with him in Nashville on the R30 tour, sitting behind his practice kit in a rehearsal room in Toronto (I’m not sure who was more nervous, him or me), and that last time at the LA Forum, his face a mask of sadness as Rush rode the circus out of town one final time; lost to one final horizon and out of sight for all of us now.

Neil died on Tuesday, January 7, 2020, in Santa Monica, California, at the age of 67. The cause was brain cancer, which he’d been quietly battling for three and a half years.

I’ll leave you with one final thing he said to me once. “Remember: nobody’s perfect,” he said, a bottle of Macallan between us. “But when you have the chance to make a decision, you can make perfect decisions. So there are no regrets, in the truest sense. And also, I hope someone who likes us, who likes Rush and our music, or admires us as people, can feel that we would never let them down.”

Neil Peart never let me down. I miss him. We all do.

The original version of this feature appeared in Classic Rock 272 (March 2020). Alex Lifeson and Geddy Lee talk about their final shows with Neil Peart in the new issue of Classic Rock.

Philip Wilding is a novelist, journalist, scriptwriter, biographer and radio producer. As a young journalist he criss-crossed most of the United States with bands like Motley Crue, Kiss and Poison (think the Almost Famous movie but with more hairspray). More latterly, he’s sat down to chat with bands like the slightly more erudite Manic Street Preachers, Afghan Whigs, Rush and Marillion.