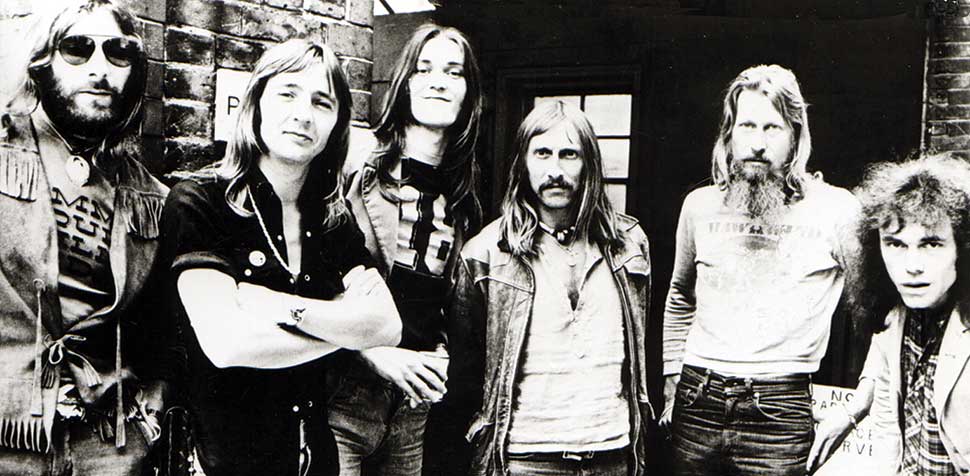

As a founding member of iconic space-rock stalwarts Hawkwind, Nik Turner helped psychedelicise a generation. When Jimi Hendrix dedicated Foxy Lady to “the cat right there with the silver face” at the 1970 Isle of Wight Festival, he was talking about Turner. Having successfully turned on the sleepy shires of 70s suburbia aboard an acid-fuelled Silver Machine, Turner brought a scene-unifying spikiness to the early-80s anarchic post-punk underground with his Inner City Unit.

Now in his mid-70s, and enthusiastically jazz-rocking alongside Billy Cobham, is this august elder statesman of the counterculture still essentially the same Nik Turner who introduced himself on Hawkwind’s debut as someone who just “digs freaking about on saxophones (groove, groove)”?

It’s God’s own earth up here. Everywhere you look there’s a breathtaking view. Lush, green and dramatic, the hills above Carmarthen, South Wales can very easily send a monoxide-lunged flatlander from the metropolis staggering back on his heels.

“Mind all the dog shit,” cautions Turner as he strides through a pack of Italian greyhounds toward the sanctuary of the farmhouse he’s occupied since 1977. Oh well, I suppose you get used to it.

Born in Oxford in 1940, Nicholas Turner grew up in the Kent seaside town of Margate. The product of a theatrical family, he remembers swapping soliloquies with an aunt who’d been in the Royal Shakespeare Company. Meanwhile, his entire family were roped into appearing in the concert parties run by his grandfather, an entertainment entrepreneur who also made movies and published a widely distributed film review pamphlet, for which young Nicholas provided enthusiastic critiques of Westerns.

“I grew up on jazz,” Turner recalls. “My mother played piano, my uncle played clarinet, my brother played trumpet and I… was very impressed.”

Fed on a diet of traditional New Orleans jazz (the first record he bought was Pee Wee Hunt’s 1948 assault on Twelfth Street Rag), Turner gravitated toward the clarinet and began taking lessons. Then, as his teens approached, he heard a sound that turned his world upside down. In order to get to school in Ramsgate, Turner had to change buses on Margate seafront. “While waiting for the bus, I used to hang around all these juke joints and penny arcades, and that’s where I first heard Earl Bostic.”

By comparison to the staid, archaic and slightly comedic sound of trad jazz, Oklahoman alto-saxophonist Bostic’s 1951 recording of Flamingo sounded fresh, sophisticated and sexy. It swung to an almost dangerous degree – you might even say that it rocked. “Hearing Bostic made me want to play the saxophone,” Turner recalls “I managed to coerce my music teacher into getting me an alto-sax and didn’t look back.

“I wanted to join the American Air Force when I left school,” he adds with a laugh. “There was an American airbase nearby and they all seemed to be having a great time. They had loads of money, loads of girls, loads of cigarettes, and the teenagers used to turn me on to the latest rock’n’roll.”

But upon leaving grammar school at 17, Turner accepted an apprenticeship from the local generator factory. Once he’d obtained his Higher National Certificate in Mechanical Engineering, he left for London, taking a job in London Transport’s Development And Experimental office, “testing brakes on buses”.

In the evenings he continued his education in West End nightclubs, alongside the fledgling Rolling Stones: “I found them very friendly, hung out with them a lot.” So much so that he eventually got the sack from London Transport for habitual lateness. Meanwhile, the practical constraints of city life saw his saxophone studies fall into neglect. “When I lived in Kent I used to play my saxophone on the beach, but there wasn’t anywhere to practise in London.”

Always looking for new experiences, Turner then joined the Merchant Navy as an engineer, initially sailing to Australia on a Christmas cruise. “It was great,” he says, deftly sidestepping the ever-yowling brood of greyhound pups that skitter about his feet to deliver a couple of cups of Earl Grey, “but there was just too much alcohol. I used to hang around pubs a lot, but this was a twenty-four-hour party, high-pressure drinking. I soon got bored and ended up spending my time in the ship’s library reading about Zen Buddhism.”

Gravitating back to Margate in 1964, Turner sold deckchairs on the beach, before launching his own seafront business: “Selling buckets, spades, kiss-me-quick hats and naughty postcards. It was also around this time that I became aware of Robert Calvert, a poet going around the pubs giving poetry readings. He was a flamboyant bohemian, a beatnik existentialist, and he had a wife who he treated like a rag. He was like JP Donleavy’s The Ginger Man, and I was like his accomplice, O’Keefe, who’d take him out and get him drunk. French friends would occasionally give us cannabis, which I found interesting. Robert turned me on to Jack Kerouac and William Burroughs… another world.”

Following his itchy feet, Turner bummed around Europe during much of the 60s, suffering a brace of near-death experiences along the way. First in Crete – “The boat I missed sank, with the loss of everybody on board” – then in Antwerp: “There was a loud clunk and the back wheel went sailing past.”

In Berlin he sold jewellery and joss sticks, while immersing himself in the city’s psychedelic club scene. “I met Edgar Froese and all these free-jazz people. They used to take me to parties and get me stoned, and to the Blue Note Club where they had all this expressionistic music. It was really fantastic, and they all said: ‘You don’t have to be technical to enjoy yourself. Just have a good time.’ So I thought, that sounds nice, I think I’ll take free jazz into the rock world.”

By the time Turner had made it to Haarlem in The Netherlands he was a roustabout in a travelling music circus. So, what does a roustabout do? “Put up a great big nine-pole tent every day! I’d bang stakes into a tarmac car park with a sledgehammer, give away flowers, work in the bar.” Obviously.

“We had a flatbed truck we used as a stage and bands would come from Amsterdam to play. There was lots of LSD about, but I didn’t get into it at first. I was a bit wary of it, really. Anyway, one of the bands that came to play was Dr Brock’s Famous Cure, which featured Dave Brock and Mick Slattery, and we palled up, got on really well. I took Dave’s phone number and when I got back to Britain I used to go and see him, stay at his flat in Putney.”

As the proud owner of a van, Turner was rapidly recruited as road manager for Brock and Slattery’s embryonic band. On attending a rehearsal, he mentioned that he also owned a sax. “Bring it along,” they said.

So he did. And the rest, as they say, is history.

Havng discovered Jimi Hendrix while in Holland and witnessed Syd’s Floyd at UFO in ’67, Turner had started to experiment, first putting his sax through a wah-wah pedal, then a fuzz box, then a doppler and flanger, until “it didn’t sound like a saxophone any more, more like a weird, distorted guitar”.

Armed with an ever-evolving combination of raga drones, psychedelicised saxophony and proto-Kraut, free-jazz improvisation, the increasingly experimental group – soon to be christened Hawkwind in tribute to Turner’s penchant for sonorous phlegm and fart production – gatecrashed another band’s gig at All Saints Hall, Ladbroke Grove. John Peel caught the show (which comprised a single, 10-minute freakout, loosely based on John Coltrane’s Africa & India and titled Sunshine Specials) and urged promoting management company Clearwater Productions to sign the band. The secret of their success? “We all got really stoned before we went on,” Turner grins. “Everybody loved it.”

And why wouldn’t they? Notting Hill, by now the band’s adoptive home, was the epicentre of London bohemia. “There was a lot of people taking drugs and living in squats. There was a lot of junkies, but there was also a lot of very creative people.”

Into this hotbed of psychoactive experimentation swept aforementioned poetic libertine Robert Calvert. “He got kicked out of his house by his wife and came to live with me,” recalls Nik. “He always had science fictional aspirations and got a gig writing copy and reviews for Friends [latterly Frendz magazine] where Michael Moorcock was Sci-fi Editor and Barney Bubbles Art Director.”

Calvert introduced Turner to Bubbles and the pair hit it off immediately. And when Turner suddenly found himself homeless, “Barney said: ‘You can come and live in my cupboard.’”

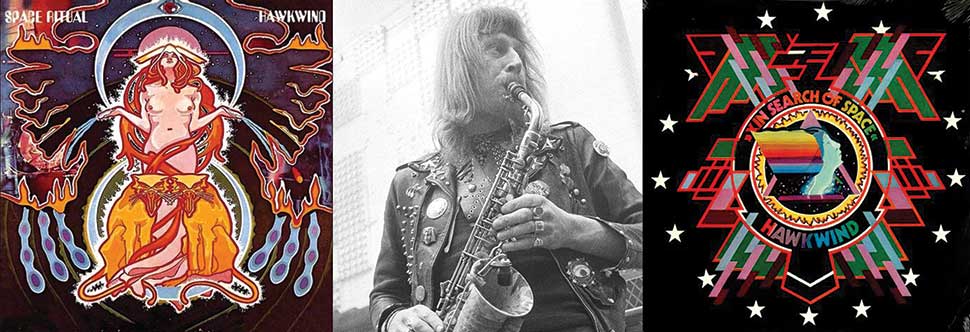

Inevitably, Bubbles started providing Hawkwind with gig posters and, invited to design a cover for the band’s second album, invited Friends’ in-house ‘space poet’ Calvert to assist. Between them, and influenced by Turner and Dave Brock’s album track Master Of The Universe, the pair contrived a sci-fi concept that comprised a die-cut interlocking sleeve, a 24-page booklet (The Hawkwind Log) and a career-defining album title, In Search Of Space.

It was at this point that Turner invited Calvert to join a Hawkwind line-up that had expanded to include a host of imagination-captivating characters. Dik Mik was another Margate reprobate, whom Turner originally met back in his kiss-me-quick seafront days. He joined as roadie, but was swiftly promoted to audio-generator operator: “It was this thing for testing radio valves. He had it on an old card table – if you stick it into a Watkins Copicat, you get this really weird sound. The sound of Hawkwind.”

Dik Mik’s mate and ex-Jimi Hendrix roadie Lemmy turned up at a rehearsal soon after the band had parted company with Dave Anderson, the latest in a long line of bassists. “I asked him if he played bass. He said no. So I said: ‘Well, we need a bass player. There’s a bass, have a go.’”

Del Dettmar was another roadie turned synth operator, while drum leviathan Simon King had previously pounded alongside Lemmy in Opal Butterfly. And Stacia? “I met her at the Isle of Wight festival and she said she’d like to dance with us. So I, laughingly, said that she’d have to dance naked with body paint on. Then she turned up at a gig in Weston-Super-Mare, took all her clothes off, got body-painted by Barney and became a piece of artwork. She was a big girl, every schoolboy’s dream. It was awesome.”

With Calvert aboard, Mothership Hawkwind went into overdrive: “Working with the band, Robert was able to do his rock opera, the Space Ritual. He was suddenly very creative, he’d written Silver Machine to be part of it, and although it was never featured in the show, it should have been.”

Silver Machine, released as a single in the summer of ’72, provided the band with an unexpected hit. Rookie bassist Lemmy – who’d provided the lead vocal when no one else could successfully nail one – was promoted, in the eyes of the mainstream at least, to frontman status. Any rancour this state of affairs caused within the band (and there was plenty) was temporarily iced as Hawkwind seized their moment to stage an interstellar, psychedelic epic.

The Space Ritual tour – featuring narrating collaborator Michael Moorcock, stunning Barney Bubbles stage sets, a light show designed by Jonathan Smeeton, a.k.a. Liquid Len, and, on Turner’s part, a flute (“Someone gave it to me. It was really bent. I think it was stolen, or someone had sat on it”) – took to the road in 1973 and expanded all sorts of minds in all sorts of directions.

It’s pretty safe to say that Turner’s initial wariness of psychedelics eventually wore off. “The first time someone gave me some acid, I found I was very excited by it, and I ended up taking LSD every day for two years. A lot of my friends were drug dealers. They’d come along to Hawkwind gigs, give me whole bottles of the stuff, and I’d give it away to anyone who wanted it, but I never tried to freak anyone out. I used to carry a bottle of Vitamin B12 around with me as I’d learnt that it could bring people down quickly off a bad trip.”

Turner’s relationship with acid came to an abrupt halt as Hawkwind played at an Andy Warhol launch party and the entire audience turned into skeletons. “I generally had a good time on it, but when that happened and all the cables turned into snakes, I thought I’d better stop for a while.”

Instead he took up yoga for two years. “Getting up at five in the morning for three hours of it. The best bit was standing on my head for ten minutes.”

Meanwhile, Hawkwind’s ongoing mission to the stars steadily soured. Silver Machine’s follow-up, Calvert’s ill-judged, appallingly timed Urban Guerilla highlighted the imprudence of boasting ‘I make bombs in my cellar’ during an IRA bombing campaign, as a BBC ban killed the single stone dead and Turner had his “floorboards torn up by the bomb squad”. Dik Mik left, followed by an increasingly unhinged Calvert, then Dettmar departed before Lemmy was sacked in ’75, following his arrest for amphetamine possession as the band toured Canada. The following year, Stacia left to raise a family and Turner was unceremoniously sacked for, allegedly, playing over other musicians’ solos.

“After Hawkwind, I’d go drinking with Malcolm McLaren,” says Turner, “when he had his shop down the King’s Road. I was with him when the Sex Pistols played the Marquee with Eddie And The Hot Rods. Johnny Rotten and Sid Vicious claimed they’d roadied for Hawkwind, so we never got called boring old farts. That gave us an amazing amount of credibility.”

In 1977, the same year he moved into his current home in Carmarthen, Turner recorded in the King’s Chamber of the Great Pyramid Of Giza while holidaying in Egypt. “I got a taxi to the pyramid and climbed up it. All these old Arabs with old muskets were trying to stop me and get money, but I just sort of bypassed them, made my way to the top, sat down and played my flute.”

Back in the UK, the recordings, with lyrics adapted from The Egyptian Book Of The Dead, were incorporated into the Sphynx album, made with Steve Hillage. Turner then embarked upon a diverse series of musical projects and collaborations that continue to this day, and include the anarchic punkadelia of free-festival stalwarts Inner City Unit; the jazzy, Hammond-driven R&B of Nik Turner’s Fantastic All Stars; ex-Hawkwind torch-carriers Space Ritual; and, most recently, his Space Fusion Odyssey album with Billy Cobham and Robby Krieger.

At 75, Nik cuts a rakish figure as he leans on the snooker table that dominates his hillside domicile. “It’s got a bit of land, bit of river, it’s fairly isolated so I rarely disturb the neighbours, and when I do, they’re very complimentary about what I disturb them with.”

He’s just back from visiting cousins in Jamaica with his two 20-something sons, where much spear fishing to languid sax-on-the-beach ensued. He beams with pride as he reveals that one of his sons has just been called to the Bar (in the legal, rather than the getting-his-round-in, sense).

Turner himself is a complex, spiritual man. He listens to an awful lot of Miles Davis. An eternal student of his chosen instrument, he never ventures anywhere without his sax, can regularly be found busking on the streets of Aberystwyth, Swansea and Cardiff on a Saturday night (“Latin jazz gets all the girlies dancing – it’s lovely”) and, if anyone’s got one, he’d be more than keen to purchase a serviceable soprano sax (“Mine’s a Chinese one, and a bit off-centre”).

Since visiting the Great Pyramid, he finds to his rather baffled delight that he has ‘healing hands’. “I went to the Festival Of Mind, Body And Spirit. They took a Kirlian photograph of my hands and said: ‘You’ve got real healing power.’ Suddenly people were investing me with the power to heal.”

In almost every way, Nik Turner seems the very model of septuagenarian contentment, but you can’t help but feel there’s a fly in the ointment. He returned to Hawkwind in 1982, remaining until ’85, and in 2000 was involved in the Hawkestra project, when a host of former members took to the stage of the Brixton Academy. Following the show, Hawkestra effectively split into two factions. Dave Brock continued with Hawkwind, while Turner remained with a smattering of ex-Hawks as xhawkwind.com. Litigation followed over the rights to the name and Brock won the case, which is why Space Ritual now trade under that name.

Then Turner’s American record company tried (in vain) to trademark the name Nik Turner’s Hawkwind: “It caused all sorts of writs to fly and a lot of bad blood was generated. The fans started taking sides and it was very sad really.”

The battle’s over, but the war appears to continue online, with opposing fan factions persisting in fanning flames of damaging dissent. Does Turner ever consider the state of antipathy between himself and Dave Brock and wonder: ‘How did we get here’?

“Yeah, I really do, actually,” he sighs. “I think we ought to just get together, and play together. Do something that can only benefit us both.”

On Turner’s planet, it seems, freaking about on saxophones (groove, groove) can still cure all ills.

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 216, in September 2015, as Nik Turner's Space Fusion Odyssey was released.