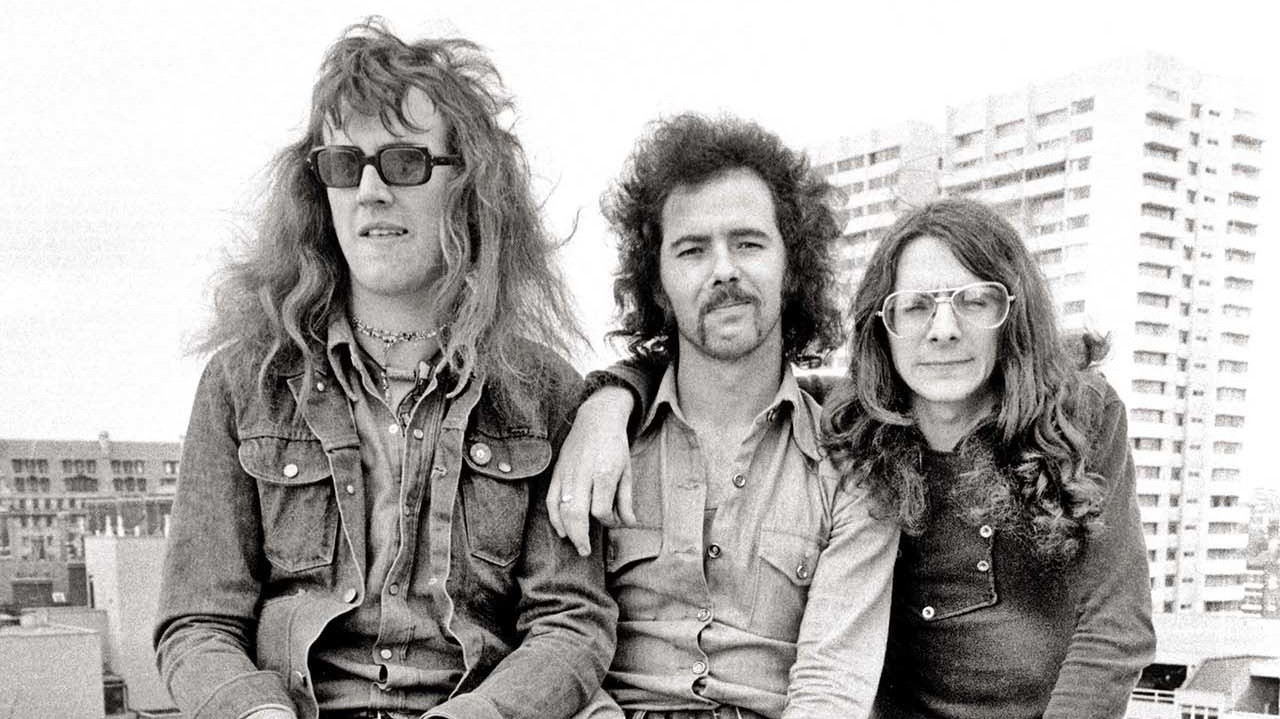

When a newly solo (and closely chaperoned) Ozzy Osbourne wanted to escape the eagle eyes of his tour ‘minders’, he knew there was one place they’d never think of seeking him out: hanging out with support band Budgie. “Ozzy used to come into our room in the hotel to get away from his lot looking for him,” Budgie bassist/vocalist Burke Shelley recalls. “He’d come in, sit on the bed and tell funny stories while having a sly puff of the magic Woodbine.”

Earlier in the 70s the abstemious Welsh trio had toured extensively with Judas Priest supporting. But if the film Rock Star depicted Priest’s later on-the-road activities in lurid detail, any such Budgie movie would give the censors no trouble, and easily be given a ‘U’ certificate. With Budgie, all the energy went into the stage act. “We might have had a pint before we went on stage,” says guitarist Tony Bourge, “but the drugs and the sex was right out the window. To be honest, I freak out if I have to take an aspirin!” Musical purity was equally important: “I didn’t even like to listen to other people in case it influenced me.”

The equally dedicated Shelley would fast from three o’clock before gigs “so I was hollow and it was easy to sing”, and performed breathing exercises to keep his banshee voice in tiptop nick. But he’s now reaping the rewards as, like a bass-toting version of the Duracell bunny, he powers on into the current millennium. Much to the delight of some famous fans: “Because of Metallica [Breadfan and Crash Course In Brain Surgery], Soundgarden [Homicidal Suicidal] and Iron Maiden [I Can’t See My Feelings] covering our songs we’re not just this seventies rock band. People come to check us out a lot. Metallica did us a great favour. I’m really pleased they like us.”

Curiously, a fresh-faced David ‘Kid’ Jensen was the first DJ to be attracted by Budgie’s charms. “Radio Luxembourg launched us,” Shelley confirms. “Kid heard our first album [1971’s Budgie], thought it was fantastic and played it and played it. He had us over there and the album took off. He was the kid with all the money, taking his mates to the fairground. That’s when I went on one of those cylinder things: you start spinning around and they take the floor away. You gotta watch it, though, when it slows down.”

But Budgie’s fortunes were certainly moving at high speed as the 70s unfolded. Formed in 1968, they’d busted their way out of South Wales with barely a backward glance. Bourge remembers: “We were going for it – so much so that we’d even have arguments with agents over money. A lot of bands wouldn’t stand their ground, thinking they didn’t want to blow gigs, but we’d go for their throat and tell them to stuff their clubs, we could get our own gigs. And we did.

“Everything was a challenge to us; we were totally dedicated. Like the Three Musketeers. One hundred per cent full on. A bit like the punks in attitude. We wanted to do well, we wanted to make albums. We had no back seat about that. We knew we’d get into a studio at some time, it was just a question of when.”

The man to help them take that step was Rodger Bain, Black Sabbath’s first producer, who later also discovered Judas Priest. He was down at Rockfield Studios in Monmouth, South Wales, on a talent spotting mission when Shelley was tipped off by an agent: “They said go there, do your best but do not play any of that stuff you’ve written. Play all the hits, Yummy Yummy Yummy [a 1968 bubblegum-pop hit for Ohio Express] or whatever. So we said: ‘Yeah, yeah’. And when the others asked what we were gonna play I said: ‘All our own stuff!’”

Budgie had already undergone a metamorphosis from Six Ton Budgie, the original four-piece with Ray Phillips on drums. “Brian Goddard [Guitarist], who’d formed the band with me, left because he got a girl pregnant and suddenly had to get a job – while we’d just packed ours in,” Shelley says. “I was training to be a surveyor. I think I’ve surveyed a lot more being in a band.”

Was it Cream that made Shelley decide Budgie could get by as a three-piece?

“I never thought about them. We ended up as a three-piece, simple as that. One fewer person to share the money with!”

Bain told the young hopefuls he had already taken Sabbath in to record demos, but Shelley was unimpressed: “‘Okay, far out. So what?’ we said. ‘Let’s play.’ We didn’t know Sabbath were heavy like us – we used to get kicked out of places for being too loud. It was dead riffy, our earliest stuff, and he liked it. So, bingo, we had a deal. The first album sold well, the second, Squawk, did better, and I guess Bain and [business partner] David Platz decided to flog us on.”

Budgie joined MCA. But unlike Kid Jensen’s more photogenic protégés, Thin Lizzy, they failed (make that refused) to cross over to a pop audience. The label suggested they cut Andy Fairweather Low’s I Ain’t No Mountain as a single, but still no luck. Not, you suspect, that they were bothered: “Burke and I wanted to keep going down the track we were on, in an original vein,” Bourge confirms, “because when you have to jump on a bandwagon you lose it.” The dilemma also prompted a line-up change when Ray Phillips “saw the cash register going in the record company and wanted to do more commercial things”. The first drummer in rock history sacked for wanting to be successful?

Budgie’s fanatical grass-roots following was in total contrast to the slating they regularly suffered from the music press. Burke took it all in good heart: “There were good writers and bad writers… I didn’t mind reviews like ‘the drummer couldn’t swing if he was nailed to a pendulum’. That was really funny.”

The fact that Budgie had a (90 per cent male) following who would turn up to see them anywhere and everywhere actually worked against them, Shelley claims: “By Bandolier [their second chart album, released in ’75], we were playing big halls. But that was a pain in the ass because MCA didn’t think they had to do anything. They took out a few ads when an album was due, that was about all. We never had strong management, which didn’t help. But either way we were established [on the live circuit] by then.”

Drummer Pete Boot only appeared on 1974’s In For The Kill. “He had the attitude, but not quite the same feel as Ray,” Bourge says. But ’75 arrival Steve Williams proved “a very good timekeeper, strong and solid”, which, the guitarist explains, was crucial for Budgie’s lumbering rock that often seemed to proceed at a walking elephant’s pace. “Ray used to get excited and speed up slightly on stage. Personally I don’t think music should be like clockwork all the time, but it was a bit of a bugbear with Burke.” In retrospect, it was precisely Shelley’s strict harnessing of Bourge’s Hendrix-inspired riffing to a rocksteady double bass drum foundation that gave Budgie their musical trademark.

In For The Kill would prove to be the band’s first and only Top 30 album. Its title track and the wonderfully titled Crash Course In Brain Surgery were particular highlights. Such wordplay marked Budgie out as hard rockers with a sense of self-mocking fun. “I’m the sort of person who likes fiddling with words,” Burke admits. “I like punning – those literary devices you can take one way or the other.” But he nobly disclaims responsibility for Squawk’s Hot As A Docker’s Armpit: “I picked that up from something Steve Marriott once said in an interview; you can just hear it in Cockney, can’t you?”

The music accompanying Shelley’s often tongue-in-cheek lyrics was at times remarkable, belying the ‘mindless metal’ tag the press enjoyed sticking to them. “We got more musical as we went on,” Bourge reckons. “Burke and I looked at chord structures, runs and scales, even down to playing minor chords with added sixths, sevenths and ninths. We wanted to do something unusual with rhythm, going in and out of time constantly and playing [instrumental] runs as though we were doing rolls on the drums.”

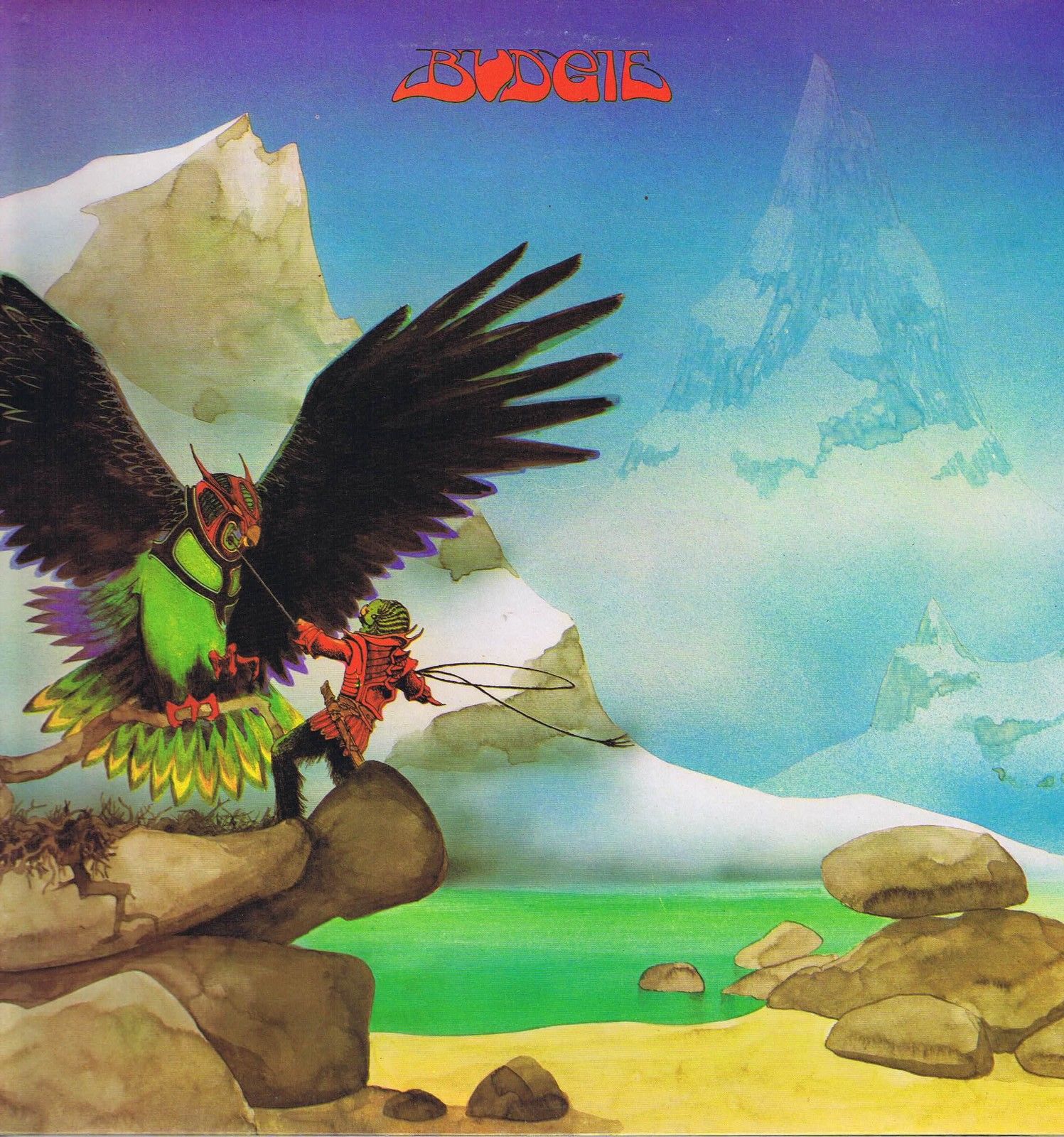

The album art was equally individual, and Roger Dean’s distinctive illustrations seemed to lend the band a thuggish charm. Three decades on, Bourge is still “gobsmacked” by Dean’s creations – a long way from his pastoral Yes sleeves. “My favourite is Never Turn Your Back On A Friend [’73]: that Budgie man catching the eagle is like something out of Star Trek, miles ahead of its time.”

In 1976 Budgie gambled everything and took the decision to try to break the States, choosing neighbouring Canada as their base for extensive tours with the likes of the then up-and-coming Legs Diamond. Shelley: “To save us flying back and forth and shifting equipment all the time, we parked our families in Toronto.”

But events at home in the UK would render Budgie obsolete overnight there. “If you think how the music of the sixties developed into the seventies, there hadn’t been a big sea change since The Beatles until punk arrived. That was a great turnaround. Suddenly we were boring farts.”

Still worse, they were on the verge of a split: “All our marriages were falling apart, everyone’s in the band at one time,” Shelley says. Tony wanted a break from it all. When you’re in a band, you never get to see the real world.”

For Bourge, 10 years was indeed enough. “I would’ve loved to have carried on, but after a while the lifestyle gets to you. Either you have the gypsy in your soul and you want to keep doing it, or it takes its toll and you want to get back to reality.” Ironically, he rates their farewell album Impeckable [their second for their new label A&M] as his highlight in terms of “being inventive playing the guitar”. No regrets, either: “I’ve not seen Budgie since I left… But I like to write a book, not read it.”

Shelley and Williams desperately started auditioning replacements for their erstwhile guitarist. “We had Huw Lloyd Langton [Hawkwind] at one point, then Rob Kendrick [exTrapeze]. Both of them at one point. Rob convinced us it was better with him alone – I don’t know how! Then he said: ‘Your name’s reasonably well-known around America. Let’s go to Texas, stay for a year and work the market over there.’

“So we went… and it was a disaster! We were stuck there with no work, running up debts, and had to get money sent to fly us home. We said to Rob: ‘You’re out of the band. But since you got us into this, you’ve got to do a tour to pay all this money back.’ We came back, toured, paid off our debts, and then we were back to square one.”

Salvation came in the unlikely shape of ‘Big’ John Thomas, a genial Brummie who had been playing lead guitar in expatriate American George Hatcher’s Band. As Shelley’s new co-writer, Thomas immediately changed Budgie’s musical direction.

Shelley: “His influences were kinda bluesy. He liked Billy Gibbons [ZZ Top]. The earlier stuff was more riffy and ponderous, a lugubrious sort of heaviness, but with John it was a more up-tempo rhythm, a slightly different style.”

Budgie’s new chapter started with the EP If Swallowed, Do Not Induce Vomiting as a statement of what was to come. And thanks to new management “with contacts and money who started putting us about a bit”, by 1979-80 the band were packing ’em in again. UK tours with Ozzy and Gillan raised the profile and, what’s more, were fun. Eyes then looked further afield. “We went over to Zagreb [in the former Yugoslavia] with Gillan for a festival.”

Like Gillan, the new Budgie lineup found huge success behind the then-Iron Curtain – especially in Poland, where, bizarrely, they found themselves bumping into fellow Welshman Shakin’ Stevens as they traversed the country. They were fêted like superstars at every turn, and I Turned To Stone reached No.1. They very nearly made an impact on the hit parade at home, too, when Keeping A Rendezvous peaked at No.71 in October 1981 in a chart dominated, ironically, by The Tweets’ irritating but suitably ornithological Birdy Song. And instead of being submerged by the New Wave Of British Heavy Metal, it seemed Budgie were surfing on it.

A storming appearance at the Reading festival in 1982, where (booked for the Friday night as a cancellation) they set an impressive standard for fellow headliners Iron Maiden and Michael Schenker to match, helped push the Nightflight album into the top 75; the following year’s Deliver Us From Evil reached No.62.

In Australia, both these and 1980’s Power Supply made the heavy rock/metal charts. …Evil in particular was very much a product of the Cold War age, and song titles like Bored With Russia, Finger On the Button and NORAD (Doomsday City) mused on an apocalyptic future.

The year of 1982 had seen Bourge make a brief return to music with original Budgie drummer Ray Phillips as Tredegar, “but I held back in my head a bit. It would take more than we had to be a top band”.

The momentum was finally slowing for Budgie, too. Some years after their third major record label, RCA, had cut their ties, Burke Shelley finally called time on the band in order to catch up on his own education.

“I did an English degree at the Ponty College of Knowledge, as they call it, at Pontypridd, near Cardiff, ” he says, “mainly cos I was home with kids and thought I’d do it while that was happening. I like that sort of thing, I’m a book person.”

He kept his musical hand in with local outfit The Superclarkes, indulging a recent fascination with black music by playing everything from The Isley Brothers to Prince-style funk.

By this point Tony Bourge had established a flourishing business far removed from his former life: “My brother was a French polisher right from when he was a youngster and, funnily enough, always wanted to be a singer!” With Budgie’s wings clipped, it seemed he may have made the right choice jumping off the rock’n’roll roundabout when he did.

- Budgie - The MCA Albums 1973-1975 album review

- Budgie release Time To Remember book

- Former Budgie guitarist John Thomas dead at 63

Then in 1995 the band’s groundwork in Texas in the late 70s began (very belatedly) to pay off. Shelley: “This guy, Joe Anthony, worked at a local radio station and loved us. He’d played Budgie over the years, but always the old tracks, nothing with John on at all. We were invited over there, and I didn’t believe what was going on… especially in southern Texas, which is Mexican-Hispanic.”

The first gig at La Semana Alegre in San Antonio received a mixed reception. “We were doing a lot of new stuff, not knowing they didn’t know those tracks. When we played the old stuff they went ape! So when we went back the following year we made sure we gave them what they wanted.”

Another reason for the crowd to go ape was the fact that Metallica, at that point America’s biggest rock band, had covered Budgie’s Crash Course In Brain Surgery on Garage Days Revisited EP 1987. When Metallica upgraded the EP to a full-length album (Garage, Inc.) 11 years later, Budgie reaped the rewards when their song Breadfan was also covered.

“I know they were fans, Lars Ulrich particularly,” Shelley confirms. “I’ve met them, but it was a long time ago – back in the late 80s, when they were touring with Anthrax. ”

With Budgie on the wing once more, tragedy struck when John Thomas had a stroke after flying back from one of Budgie’s US ventures. “Maybe he was one of those DVT [deep-vein thrombosis] victims,” ponders Shelley, who rates him “lucky to survive with everything ticking and working”.

Amazingly, Thomas fought his way back from illness to play with the band in September 2001’s Legends Of Welsh Rock event in Cardiff, where Budgie topped a weighty five-band bill. The guitarist – ironically dressed in an undertaker-style frock coat – seemed to carry it off, but all was not well behind the scenes.

“Being in a band is like being on a tandem,” drummer Steve Williams explains. “If one of you gets tired, it makes it harder for the others. I felt John was getting tired, and the enormity of what had happened to my friend suddenly dawned on me in the middle of the show.

“It was brave of John, but that spark, that twinkle in his eye, was missing. I talked to Burke, and he felt the same. I never for a moment thought it would be permanent, but I knew that it just wasn’t right, and gave my full support to finding someone to stand in.”

Session man Andy Hart was that someone in 2002-03, but he recently stepped down in favour of Simon Lees, born two years after Budgie’s first flight, whose track record includes working with ex-Judas Priest singer Al Atkins.

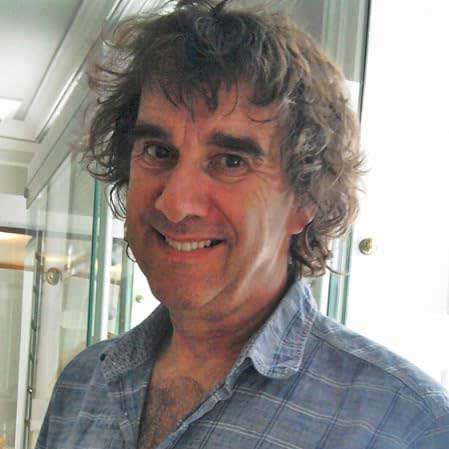

Certainly Tony Bourge was never likely to give up his thriving business to rekindle his partnership with Burke Shelley, much as the bassist would welcome the prospect. “I’d like to have a knock with him just for the crack, just for fun, but he’s a family man, he’s got it sorted. You’ve got to remember how old we are now – a lot of people are moving into their slippers!” But that’s clearly not an option for Shelley, who still looks every diminutive inch the pocket battleship he’s been over the years.

The first five titles of Budgie’s back catalogue are about to be reissued in expanded, remastered form via their own label, Noteworthy, while The Last Stage, the album they were working on when dropped by RCA in 1983-’84, will deliver a dozen or so unheard tracks including a version of Nutbush City Limits and stage favourite Rock Your Blood.

“People are buying the version of Breadfan where we coughed in the studio, or a live show from St Albans City Hall 1978,” says Shelley, “so this is collectable because it hasn’t been heard before. The next thing on my mind is a new album, something meaty… the rest is just fluff on the sandwich!” Budgie returned in triumph to San Antonio in summer 2002 to play a set that emerged on CD as Life In San Antonio, while this March saw them revisit Poland for the first time in two decades with shows in Warsaw and Krakow – Shakin’ Stevens sadly absent this time around!

Says Williams: “If you like sweaty, whiplashinducing, galvanised metal, designed for ears and not eyes, you’re welcome at our shows any time.”

This feature was originally published in Classic Rock 65.