NSFW: Nine Inch Nails' Happiness In Slavery

The story behind Trent Reznor's gruesome bondage video

In 1992, Trent Reznor was in as angry a place as he’d ever been. Dark, spiteful and bitter, he had endured a difficult year. There had been Nine Inch Nails’s hilarious miscasting as a support act for Guns N’ Roses and a subsequent European tour in which Reznor’s band was savaged by a crowd hostile to their bleak fury. There had been a long and heated argument with his record label TVT, who Reznor accused of creative interference and of misbranding his band as synthpop. And there was also the fact he was Trent Reznor – as Rolling Stone once memorably rephrased Philip Larkin, hatred was to him what daffodils were to Wordsworth.

In secret, Reznor had started laying down his anger on a new record that he did not want his label to know about. TVT had demanded a follow-up to his debut Pretty Hate Machine and had made it clear they wanted Pretty Hate Machine 2 and nothing else. Reznor, increasingly influenced by the industrial fury of Ministry and Godflesh, had other ideas and was forced to go underground to record behind his label’s back. The results were Broken, an EP co-produced with Flood and, in part, recorded in the Tate house in which Charles Manson’s ‘family’ had committed their notorious murders in August 1969.

Given the atmosphere in which it was made, to expect anything other than the oppressively heavy, violently fury of its eight tracks would have been foolish, but Broken is such a dense, savage and aggressive listen that it was shocking in its harshness. Reviews made use of words like “intense”, “nihilist”, “rabid, “spiteful” and “vicious”. One reviewer described it as “like a harrowing rape account”. And that was before they saw what would become one of the most notorious music videos of the ‘90s.

When Reznor began to think about a video for what he felt was Broken’s standout song, Happiness In Slavery, he had three things in mind. Firstly, he wanted to truly reflect the dark feelings he had poured into the Broken EP and, hence, the song. Secondly, he wanted to create something that was not the same old MTV video.

But it was the third element that was perhaps foremost in his mind. While he had been making Broken, his row with TVT had reached a head, and led to Nine Inch Nails moving to Interscope. Reznor had had very little control over this and, typically, was unhappy: “I didn’t know anything about Interscope. And I was real pissed off at [Interscope boss Jimmy Iovine] at first because it was going from one bad situation to potentially another one.” Reznor made it known from the outset that was not going to make life easy for his new label, saying he pulled a “raving lunatic act” on them. To his surprise, though, they were willing to do whatever he wanted, giving him full artistic licence. He immediately decided to put them to the test with the Happiness In Slavery video. “When I signed to Interscope,” he said later, “I made it clear I wanted artistic control over what I do. Granted, [the video] is an extreme example …”

Reznor invited the young documentary- and short film-maker Jon Reiss to the Tate house for a meeting. He told him: “If done right, this could be a bizarre and interesting visual experiment that does not look like a typical video.” He also pointed out that he was sick of the way MTV had turned music videos from a potential artform into “three-minute commercials for the public to be told what to buy and what to like.”

Reiss, who had documented the underground punk scene on America’s west coast and in Europe, knew exactly what he meant. “Trent Reznor was looking for filmmakers who had never done a music video before. He didn’t want anyone polluted by the process,” said Reiss. “Trent wanted to do a video that didn’t have any limits. His guidelines were ‘consensual S&M’ and ‘gears grinding flesh’.”

The latest news, features and interviews direct to your inbox, from the global home of alternative music.

Reiss came up with a concept based on Octave Mirabeux’s The Torture Garden, a French novel in which a sadist visits a Chinese prison and orgasms while inmates are flayed and whose blood then feeds the beautiful gardens in which they are tortured. “I decided to update the story making the ritualised relationship between a man and a machine,” said Reiss. “I also made this torturous relationship purely voluntary – so that the men were giving themselves to this process, ritual, transcendence.”

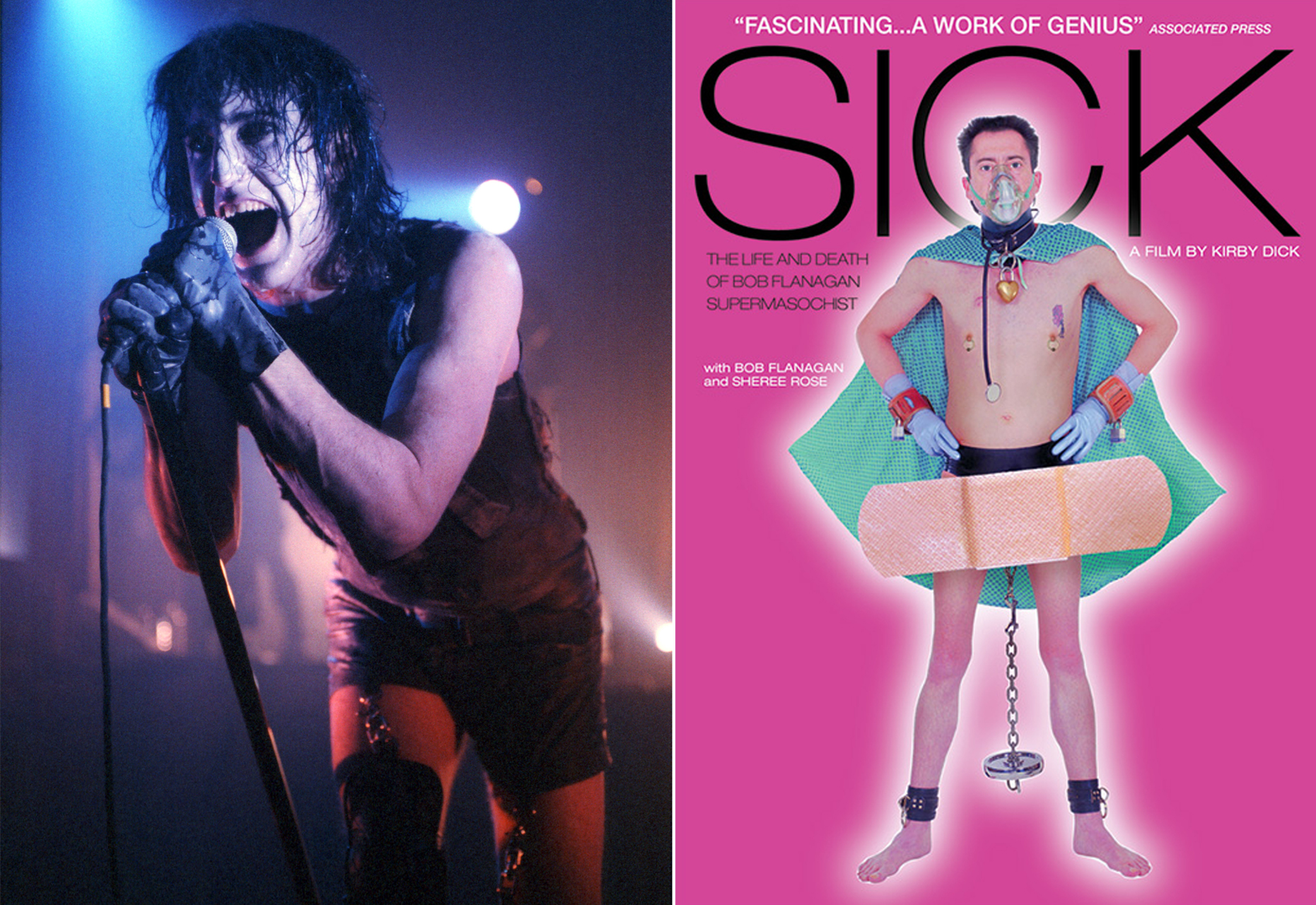

Reiss approached a friend, the performance artist Bob Flanagan to star in the video. A cystic fibrosis sufferer, Flanagan already had a reputation for extreme acts: notoriously, he once hammered a nail through his penis. Reiss set about torturing him for the video. It begins when Flanagan, suited, willingly walks into a torture chamber. He strips naked, then lies on a table whereupon he is savaged by machines, mechanical claws cutting him then tearing out his flesh as his blood feeds a garden below. Throughout, there is graphic full frontal nudity and gore. “I was left to operate the device that pulled on Bob’s testicles,” said Reiss. “I have the distinct pleasure of having made Sheri [his partner] jealous.”

Flanagan appears to derive pleasure from his pain and, as the song climaxes, so the machines reach a frenzy, crushing his genitals, ripping open his stomach, then mincing his body. Finally, as the machines return to their starting positions, Reznor walks through the door of the torture chamber as if about to take part in the act himself. “We had a feeling people were not going to be happy with the piece,” said Reiss with considerable understatement.

MTV were furious. Reznor was a rising alternative star and they had been desperate for his next video. Clearly there was no way they could air something showing full frontal nudity, genital-crushing and pouring blood (even though much of the gore was really only mashed banana and chocolate). Canada’s Much Music did dare to show it, and the programmer responsible was sacked the next day and while some channels screened it late at night most banned it outright. And so, of course, it became instantly mythical.

“This video was basically a Fuck You to the industry,” said Reiss, who is still sitting on a longer, seven-minute edit of the video. “I heard his label freaked out as well – but then took the credit for what a brilliant marketing move it was! It went viral on VHS cassette throughout the industry – this is in 1992 – well before the prevalence of the internet.”

Reznor denied creating it for shock value. “These were the most appropriate visuals for the song,” he told Billboard in 1992, before conceding that perhaps “he had flushed some money down the toilet” in making a video no one would see. Then again, he added, Nine Inch Nails had done reasonably well without MTV’s support thus far.

His appetite whetted by the Happiness In Slavery video, he would go on to make a now legendary short film with Throbbing Gristle’s Peter Christopherson to accompany all of the Broken EP. But Reznor, who says the Broken film “makes Happiness In Slavery look like a Disney movie”, subsequently refused to release it as he was concerned it would overshadow the record (it has subsequently leaked online).

He had no such fears about Happiness In Slavery however. He sent the first copy of it to his mother. It is tempting to wonder, as executives at MTV freaked out, and as censors leaped to ban it, quite what she made of it.

Tom Bryant is The Guardian's deputy digital editor. The author of The True Lives Of My Chemical Romance: The Definitive Biography, he has written for Kerrang!, Q, MOJO, The Guardian, the Daily Mail, The Mirror, the BBC, Huck magazine, the londonpaper and Debrett's - during the course of which he has been attacked by the Red Hot Chili Peppers' bass player and accused of starting a riot with The Prodigy. Though not when writing for Debrett's.