"It was very British, but it shot round the world. It changed music": How the New Wave Of British Heavy Metal was born, by those who were there

In the late 70s, rock music was given a steel-booted kick up the backside by a new breed of band. The NWOBHM would go on to rule Britannia – and the world

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

Less than a decade after it had been forged in the white heat of the late 60s, British rock was in trouble. Its original pioneers had either split up, lost touch with reality or were spiralling into drug-addled irrelevance, their thunder stolen by both a wave of platinum-plated American bands and the incendiary punk movement.

It may have been down, but British rock wasn’t quite out. As the 1970s hurtled towards its conclusion, a new wave of heavy bands from all corners of the United Kingdom sparked off a grass-roots revolution, rewriting the rule book on how things could be done and giving their more established counterparts a shot in the arm. Its leading lights would go on to achieve the unthinkable, but even the bands who didn’t and got left behind – the foot soldiers, also-rans and no-hopers – were heroes in their own way.

For a few glorious years in the late 70s and early 80s, these small islands were the epicentre of the most vibrant, exciting and groundbreaking scene around. This is the story of how British rock heavied up and changed the world once again…

The 1960s marked the dawn of the rock era. Pop’s simple attractions had given way to something harder, heavier and more grown up, and the branches of the musical tree began to spread wildly: blues rock, psychedelia, West Coast rock, East Coast rock, country rock, heavy metal. A generation of impressionable would-be musicians were paying avid attention.

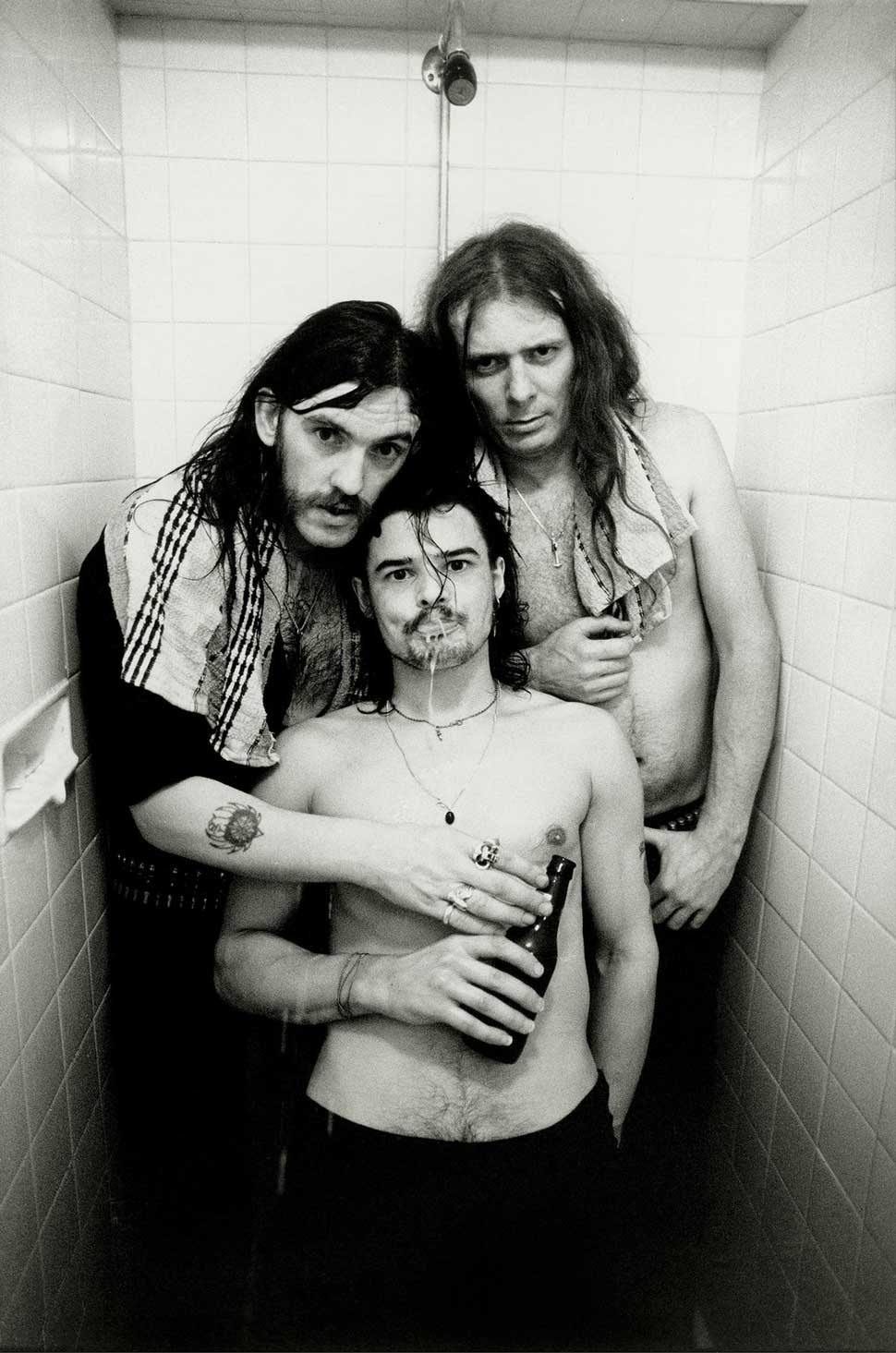

Fast Eddie Clarke (ex-Motörhead): Playing music was always the thing for me. I started when I was twelve or thirteen, started to see Eric Clapton and just wanted to do it. Then Hendrix comes along and blew me fucking head off.

Biff Byford (Saxon): I grew up in the 1960s. I listened to all the pop groups – the Rolling Stones, The Beatles, The Kinks. My mum was a pianist, and my friend was in a blues band. We’d watch him play and I decided to learn the guitar a little bit. That’s when I wanted to get involved in music.

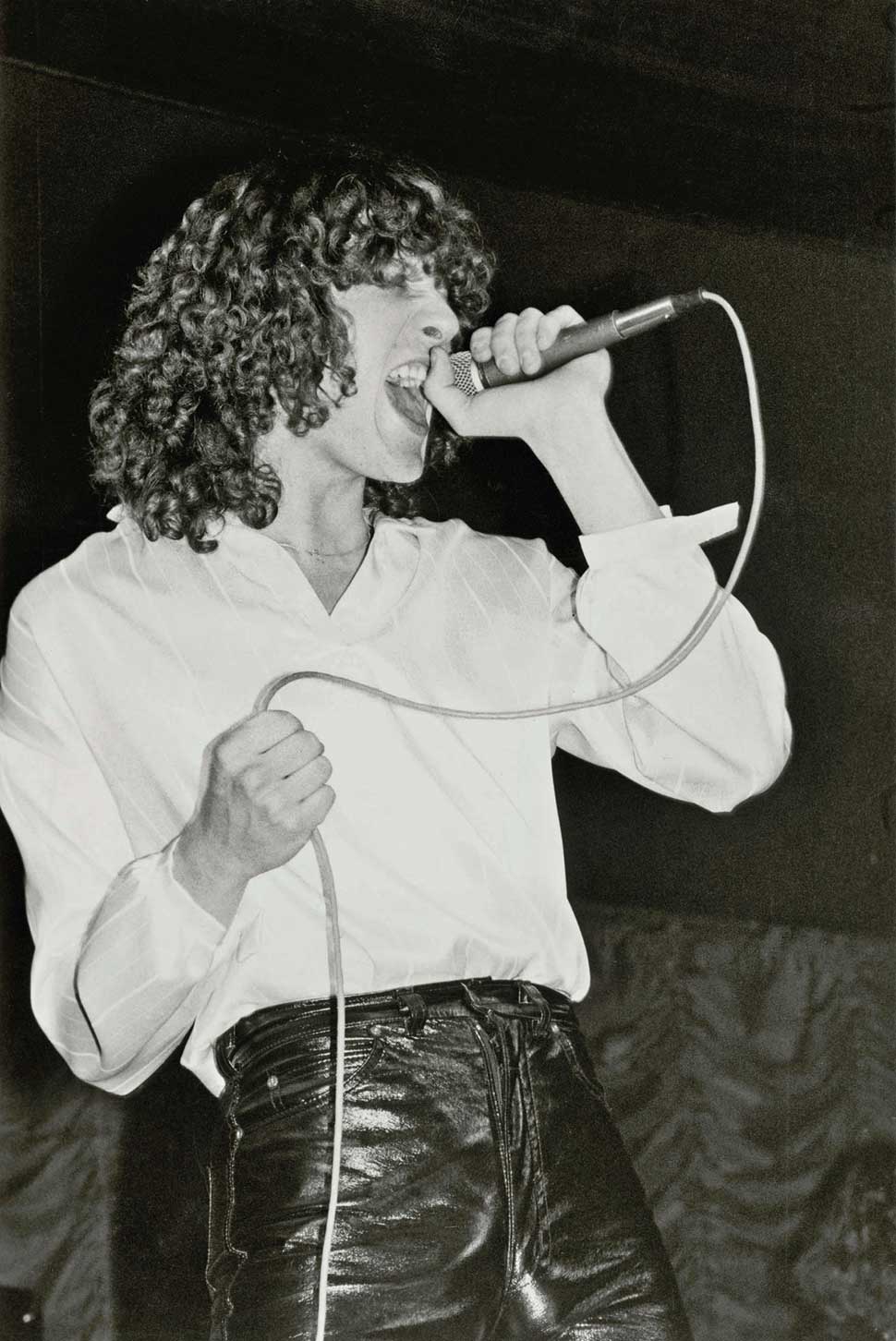

Joe Elliott (Def Leppard): The first artist that I got into was Marc Bolan from T.Rex. Everything he did, the whole catalogue. I wanted to be Marc Bolan. David Bowie when he did Starman on Top Of The Pops – that blew me and everybody away.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

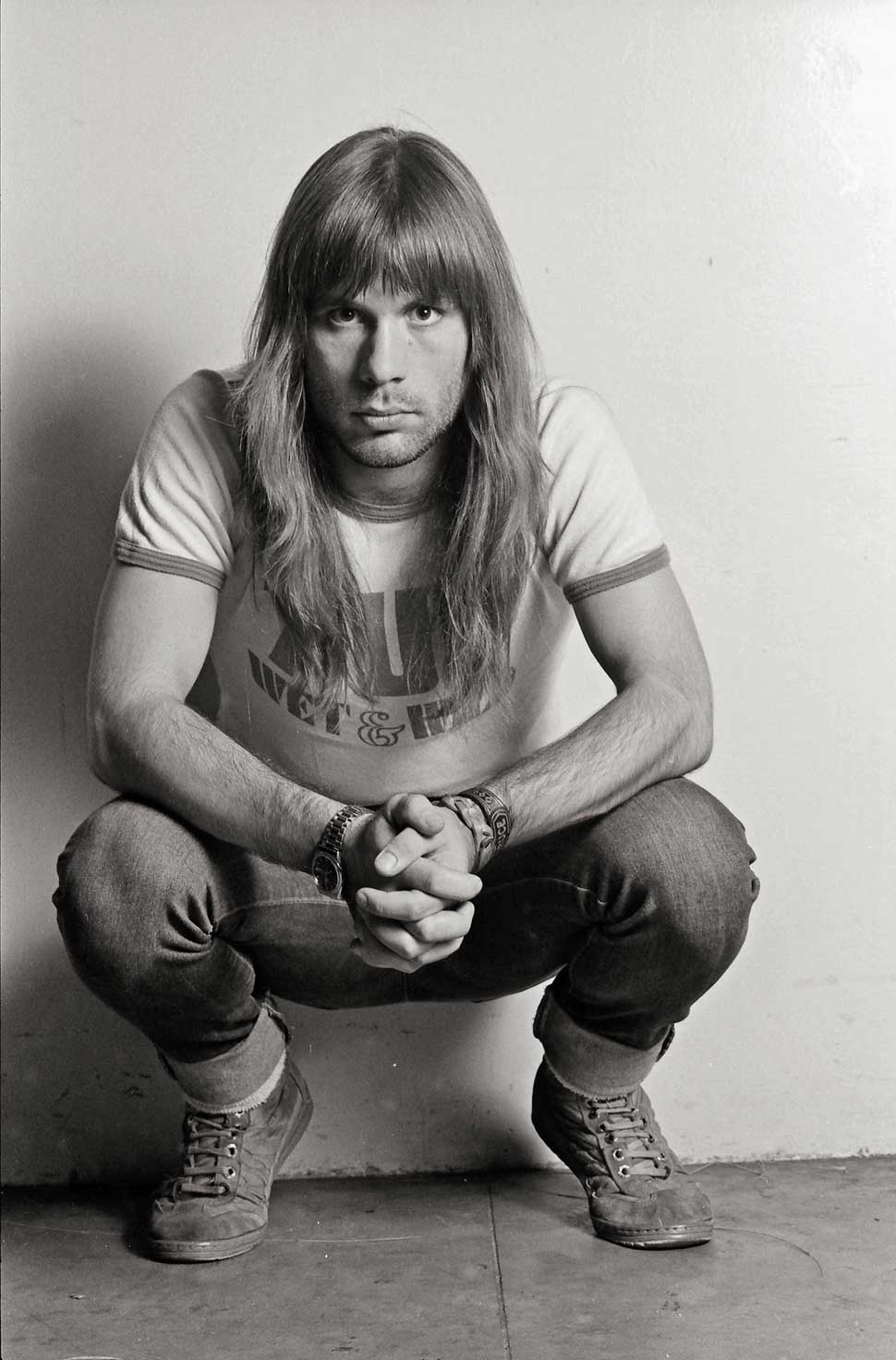

Steve Harris (Iron Maiden): I used to listen to The Beatles and The Who and stuff like that. Then I started getting into more rock stuff, and that led to Wishbone Ash and then on to prog. Those early Genesis albums gave me goosebumps.

For many of these aspirant musicians, music offered an escape from the drudgery of real life, if not a direct route to fame and riches.

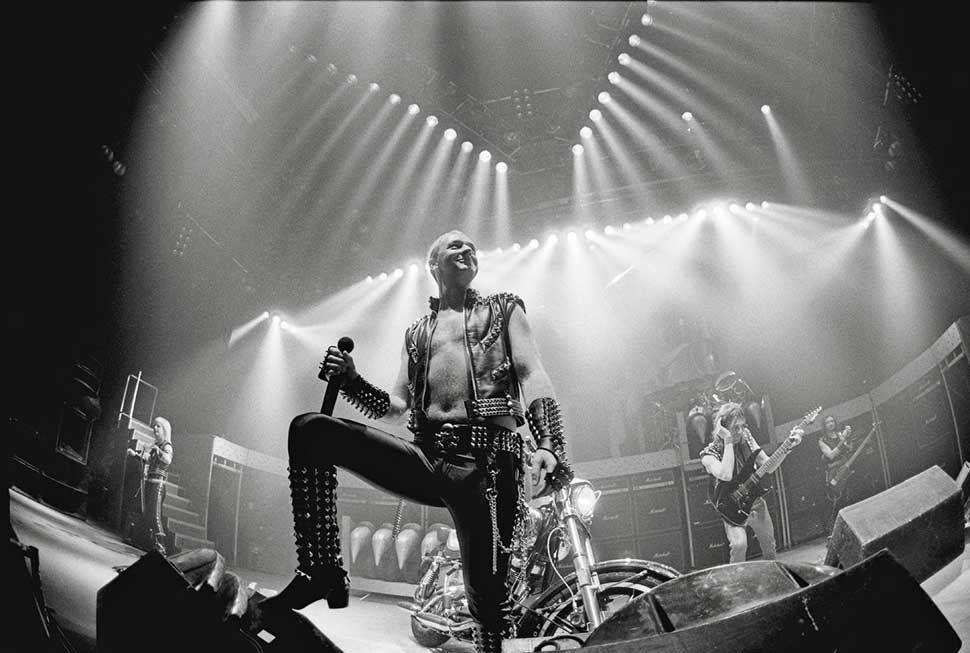

Rob Halford (Judas Priest): We all came from tough working-class backgrounds. Walsall and West Bromwich were pretty bleak. We could all relate to the need and the want of trying to break out of an unpleasant cycle.

Fast Eddie Clarke: I come from a working-class background. I never thought I’d make money out of music. My dream was to play my guitar and earn enough to eat and live. If I could do that I’d be happy for the rest of my life.

Biff Byford: In Barnsley, your main job choice was going down the pit. Mining was a good living, it wasn’t awful. But I wanted to see the world a bit, meet some girls.

Joe Elliott: The ambition was just to be in a rock band. It’s like: “I don’t want to work in a factory all my life.”

Rob Halford: We never really sat down as a band and said: “What’s the battle plan?” Like any great thing that comes out of Britain, it had some apprenticeship, some dedication behind it.

Fast Eddie Clarke: None of the musicians back then wanted stardom or big fucking wads of money, they just wanted to play their music and make a crust. When I joined Motörhead it was just something to do. We didn’t want to become stars, it was just a chance to play.

Brian Tatler (Diamond Head): When I started Diamond Head in 1976, the dream was just to make records and enjoy it. I had no idea how you got from forming a band with your friends to playing something huge like Wembley Stadium. It seemed impossible.

By the mid-70s, things had started to change. For some bands, the lure of America proved irresistible and they spent their time touring there, hoovering up money and whatever else was available. For others, years of success had bred complacency, arrogance or both.

Fast Eddie Clarke: I went to see Led Zeppelin at Earls Court in 1975. Fuck me, there was a forty‑five minute drum solo, and Jimmy Page was fucking about with his guitar for an hour. You’d sit there and think: “I didn’t fucking come here to see this.”

Ashley Goodall (EMI A&R man):

I don’t think there were that many great rock bands around. A lot of the big guys had run out of steam by ’76 or ’77: Deep Purple, Led Zeppelin a little bit. Queen were sort of carrying on, being quite pop, but they had gone out of favour a bit.

Fast Eddie Clarke: The prog rock lot had gone a bit over the fucking top. The Yes’s and Genesis’s had lost sight of everything. They all had servants and Rolls-Royces. I just thought: “Fuck off you silly c**ts.”

Brian Tatler: I loved Pink Floyd to death, but I couldn’t get tickets to see them, and if you did get tickets then you’d be among ten thousand other people in a great big hall. At least in the pubs or clubs there was some excitement, some sweat.

Andy Dawson (Savage): Things were getting a bit tame, and then punk came along and kicked everybody up the arse.

British punk was born in the underground clubs of London but rapidly spread outwards, lighting up the cities of Britain like a series of detonations. Its plastered-on snarl and nihilistic world view was the antithesis of everything that had gone before. Love it or hate it, punk had to happen.

Brian Tatler: I hated the Bay City Rollers and The Osmonds and all that stuff, so when the Sex Pistols appeared on TV I thought it was great. I could play like Steve Jones, whereas I couldn’t play like Ritchie Blackmore. I was like, “Let’s not hang around – these guys are doing it.”

Jess Cox (Tygers Of Pan Tang): Most of the punk bands were awful, but some were good. We were well into The Clash, the Pistols, stuff like The Tubes. But we all loved Led Zeppelin and Black Sabbath as well.

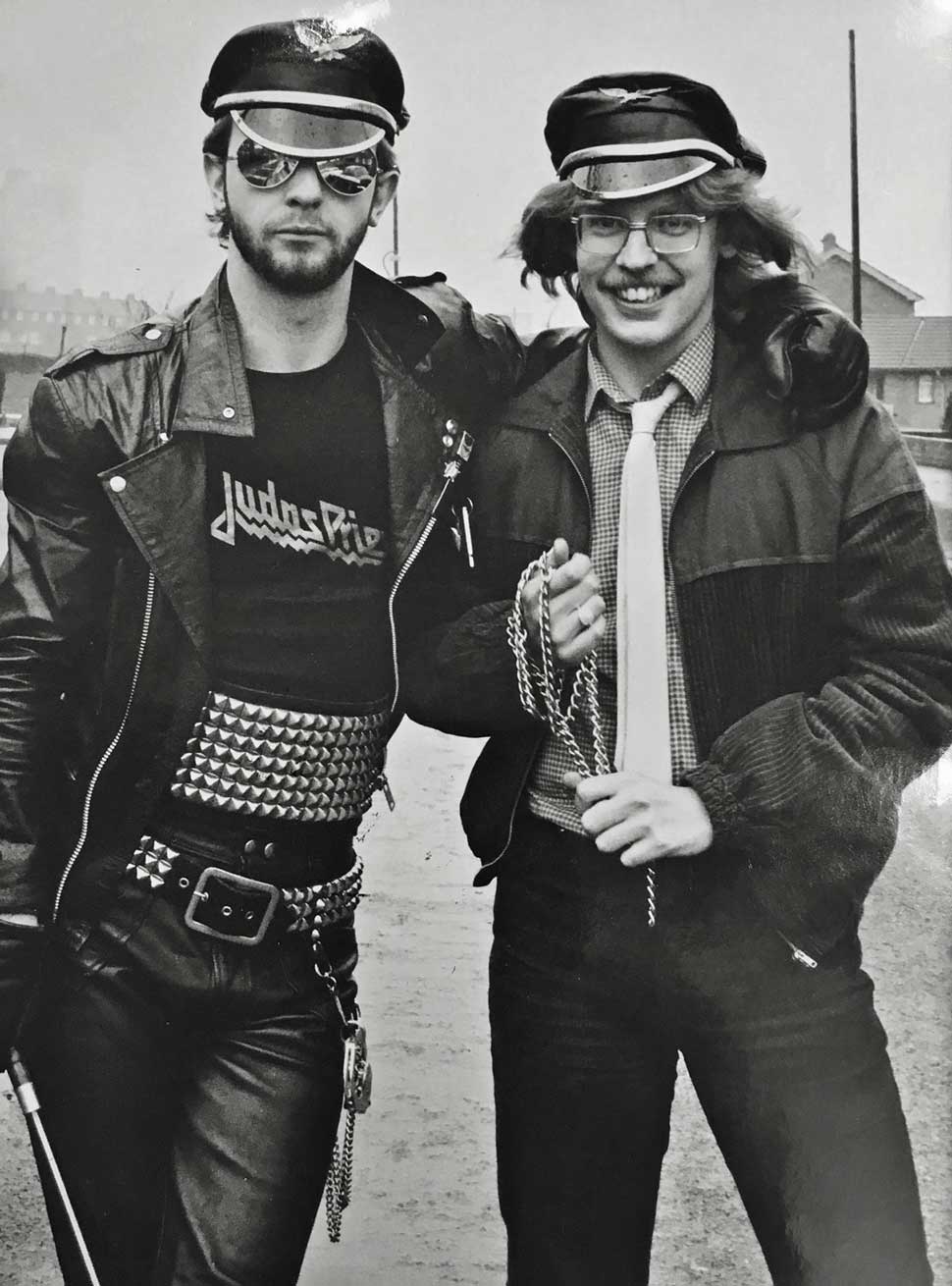

Biff Byford: We didn’t really get on with the fashion – the bloody safety pins through the noses. We did take on the studs, though. There were a lot of studded jackets around at the time. We nicked that and turned it into our own style, as did Motörhead.

Fast Eddie Clarke: Motörhead were accepted by all the punks. We had long hair, but we wore leather jackets and we played loud and fast. We were in the same family.

Rob Halford: The press just said: “Fuck off, heavy metal, it’s over.” We said: “No it’s not.” We saw that punk was gonna be a short-lived experience. I found it very insulting that someone would dismiss not only the bands but also the fans. So that made us even stronger.

Thunderstick (Samson): Punk came along and swept everything away. The first time I saw it, I thought: “These guys can’t play their instruments.” But then I quickly realised that it wasn’t all to do with just playing the material. It was about a lifestyle.

Fast Eddie Clarke: Punk was refreshing. Especially when they said: “Fuck off everybody.” I’d been saying that for years.

Brian Tatler: Punk brought things back down to the grass roots, didn’t it? You could go and see a band in the pub. The New Wave Of British Heavy Metal adopted the do-it-yourself attitude.

Punk may have pitched itself as the sworn enemy of the ‘dinosaur’ bands, but it had the unforeseen side effect of galvanising some of the more clued-in longhairs. Motörhead, formed in London in 1976 by former Hawkwind bassist Lemmy, were one such group. Barnsley’s Son Of A Bitch – soon to change their name to Saxon – were another.

Fast Eddie Clarke: The audiences at our early gigs were disenchanted rockers. They had long hair and leather jackets but they didn’t like the punk thing. They were into Deep Purple and Black Sabbath back in the day, but they’d fucked off to America.

Biff Byford: Motörhead were flying the flag. They were big way before us. They were the ones busting down the doors.

Fast Eddie Clarke: It was a very British form of music. The fucking Americans weren’t coming up with anything, anyway.

Andy Dawson: Saxon were going strong well before the New Wave Of British Heavy Metal kicked in.

Biff Byford: We were playing quite a few shows with a lot of youngsters in the crowd. It was quite an aggressive stage show. There was a lot running around and shouting. I think we took that from the punk bands.

Fast Eddie Clarke: I thought Saxon were fucking blinding. They were a great band, they had great tunes, and what a great bunch of guys. When they supported us on the Bomber tour I used to go out and sneak into the crowd to watch one of their tunes, See The Light Shining, every night.

Biff Byford: We were always chasing a record deal. We’d send cassette tapes off to people. If they didn’t like one lot of songs, we’d throw them in the bin and write some more songs.

Around the same time, a gang of streetwise East Londoners were making a name for themselves in the pubs and clubs of the capital, most notably the Ruskin Arms in Manor Park. Their name was Iron Maiden, and they were led with gritty ambition by bassist Steve Harris.

Rob Verschoyle (childhood friend of Steve Harris): I met Steve when I was twelve and he was ten. The difference between the rest of us and Steve was dedication. He’d be playing bass all the time. He became a trainee draughtsman, but he gave that up to concentrate on playing. His whole life was like that. Anything he did, he went at it a hundred per cent.

Steve Harris: I wouldn’t say I’m a control freak. I just like to get things done.

Neal Kay (DJ/founder, Heavy Metal Soundhouse): Since 1975 I’d been building up a small venue in Kingsbury as a heavy metal discotheque. It was known as The Bandwagon in the Prince Of Wales pub, but I rechristened it the Heavy Metal Soundhouse. The main room held about seven hundred people, and we had a fuckin’ ginormous sound system. I kept badgering Geoff Barton at Sounds to come down, because I knew it was unique, and a great press story. It took a long time to convince him but in the end he came.

Geoff Barton (writing in Sounds, August 1978): “The decor resembles Dodge City, American B-movie Western style but, with alternating flashing lights/darkness, your eyes never really adjust to notice that much detail. The Bandwagon and the music that’s played there is very much a present day reality, no matter what the fashion pundits might tell you. And to me, and a goodly number of other punters, it’s like a little bit of heaven on earth.”

Neal Kay: After Geoff Barton’s double-page spread in Sounds, suddenly all these demo tapes started arriving from oppressed bands who couldn’t get out. Among these tapes was the Iron Maiden demo.

Steve Harris: We did a four-track demo and gave it to Neal Kay.

Neal Kay: Steve and [Maiden singer] Paul Di’Anno brought it to me on one of the week nights. Steve said: “’Ere, mate, give this a listen when you’ve got a minute.” I said: “You’ll be lucky. I’ve got millions of tapes to listen to.” But that night I put it in the player and listened to it. I thought: “Fuck me, this is going all the way.” I phoned Steve up at two am and said: “You’re going to be really rich, because what you’ve got here is nothing short of brilliant.”

Steve Harris: He played it at the club and people began voting for it as their favourite track. We started getting into these Sounds charts, which were compiled from requests there. That’s what got the ball rolling for Maiden.

Biff Byford: We played some universities with Iron Maiden, supporting a band called Nutz. The people who booked it said they’d never seen bands go down so well that sounded so crap. We quite liked that.

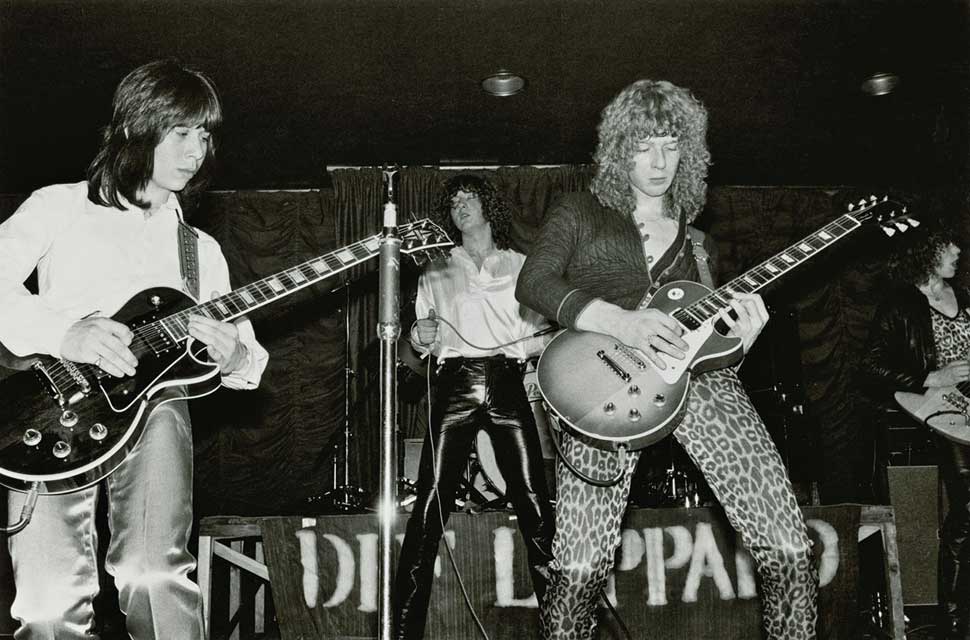

One hundred and fifty miles up the M1 in Sheffield, another equally ambitious group of youngsters had their eyes firmly set on rock stardom. Singer Joe Elliott, bassist Rick Savage and drummer Tony Kenning had formed the band Atomic Mass while still in their mid-teens. By the time they played their first gig, in a school canteen, they had changed the band’s name to Def Leppard.

Biff Byford: Def Leppard were very young. They were four or five years younger than we were.

Joe Elliott: We were a bunch of kids destined for factory life. We knew the opportunities we were being given. We were not going to screw this up.

Rick Savage: We were teenagers, and we had this belief that anything was possible. When that way of thinking is moulded into the group at that very early stage, it never really leaves you.

In January 1979, Def Leppard released their self-titled debut EP. With copies glued together by Joe Elliott and his mum, it was available via mail order and at gigs, costing the princely sum of £1.

Biff Byford: Def Leppard did the EP and sold it in Sounds. I like that early stuff. It was killer.

Joe Elliott: We were just a bunch of teenagers messing around, doing what we felt was right. But Getcha Rocks Off did have a vibe about it that was above and beyond what everyone else seemed to be doing. I think there was a good reason we got the deal that hundreds of other bands couldn’t seem to get at the time.

Andy Dawson: Everybody I knew went out and brought that EP. There was a rock disco on Friday, and that would be played every time.

Joe Elliott: That naiveté can really drive you. And we weren’t stupid. We learned our craft from listening to other people. We were students of Pete Townshend and Ray Davies and Plant and Page and Lennon and McCartney. We knew a good song when we heard one – and we just tried to rip off as many of ’em as we could.

Geoff Barton: After much phone-call badgering, Joe Elliott enticed me up to Sheffield in June 1979.

Joe Elliott: The first time Geoff Barton came to see us play was at Crookes Working Men’s Club in Sheffield. I picked him up at the train station in my van – a two-seater so you could throw shit in the back.

Geoff Barton: I was bowled over. They put on a hugely impressive performance for the cap-wearing, ferret-bothering audience. A subsequent double-page feature in Sounds, plus strong support from local station Radio Hallam, helped secure them a contract with Phonogram.

Fast Eddie Clarke: Def Leppard I never really got along with. I know them now, but they weren’t really my cup of tea back then. They were like a girly band, trying to appeal to girls.

The media was so enamoured with punk that it failed to notice this new movement springing up under its nose. All around the country, new bands were appearing at a weekly rate. In the north-east there were the Tygers Of Pan Tang, Raven and Fist. Scotland had Holocaust. The East Midlands had Witchfynde and Savage, while the West Midlands was represented by Diamond Head, the West Country had Jaguar. London had Samson, Angel Witch, Girlschool and, of course, Iron Maiden. And that was just the tip of the iceberg.

Ashley Goodall: The punk thing was starting to get boring, to be honest. I noticed there were a lot of kids going to heavy rock events. There was a bigger audience at The Bandwagon than there was at clubs like The Marquee.

Andy Dawson: Bands like Thin Lizzy, UFO and the Scorpions seemed so far away. They seemed other‑wordly. But then you’d see some of these bands playing your local venue, and you started to think: “Maybe we can do it as well.”

Jess Cox: What made us want to be in a band? I guess the answer is that it was easy to meet girls.

Biff Byford: There were tons of gigs, tons of girls.

Andy Dawson: A lot of bands were still playing covers. We used to do a set that would be half made up of songs from Live And Dangerous and half from Strangers In The Night. Then we started introducing our own songs.

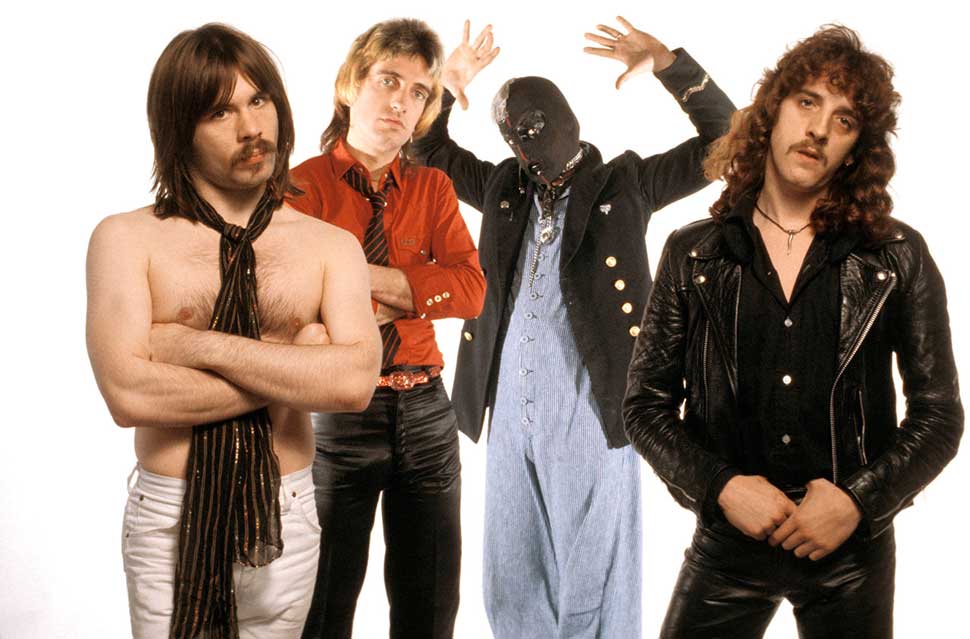

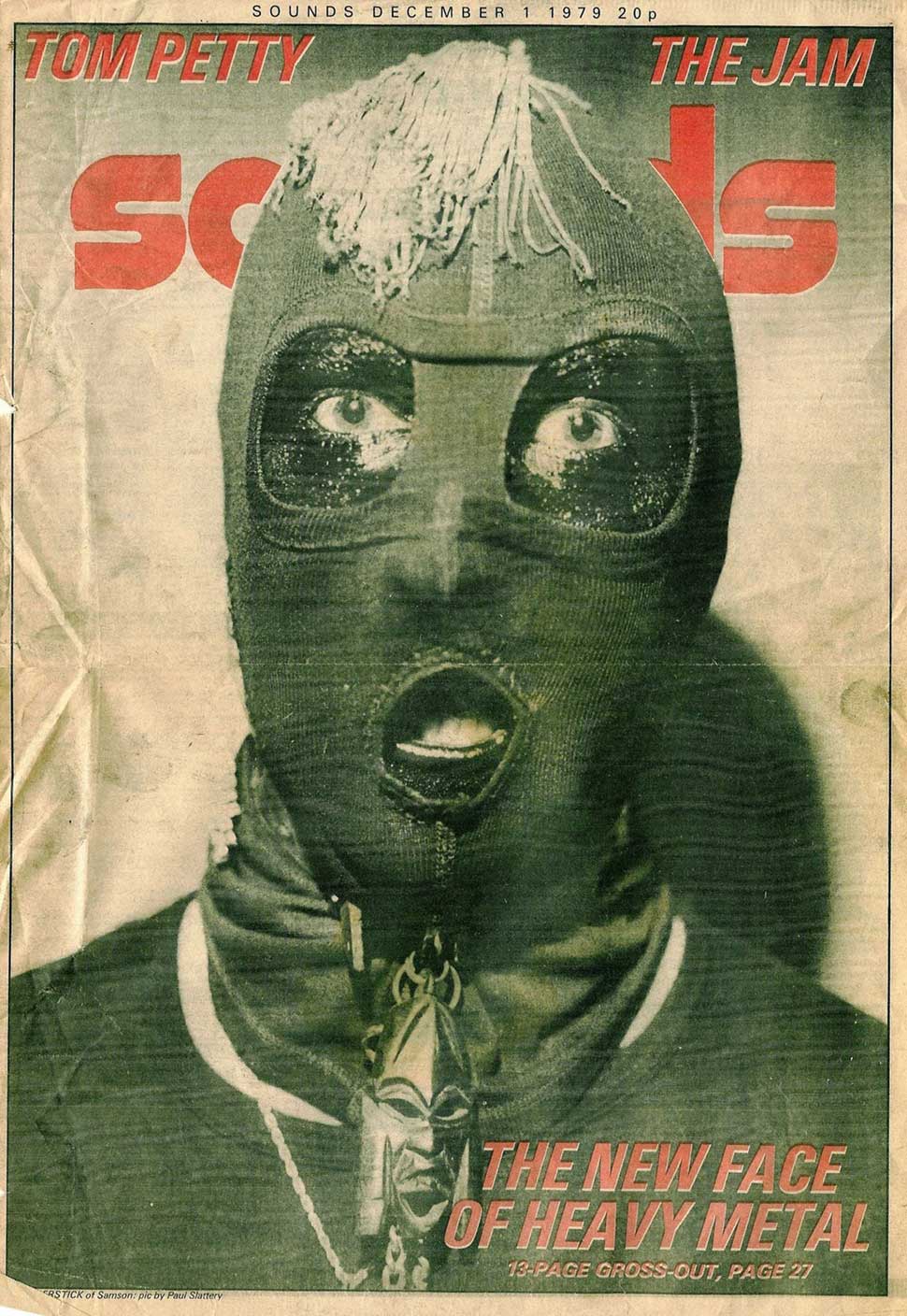

Thunderstick: Samson was the first band I joined that actually had a manager. We got a retainer wage, which was pretty good. We used to rehearse in a farmer’s shed, with all these rotting vegetables in it. It had one power point that we’d run everything off.

Jess Cox: We were just out to make a glorious racket. We had no idea how the hell you structure a song. If you listen to some of our early tracks, you’ll find that there’s four bars here and seven bars there.

Biff Byford: We were playing really fast stuff – it was all Never Surrender and Stand Up And Be Counted. Just getting out on the streets, that was our message in those days.

Jess Cox: We had drainpipe jeans and fringes. I know that sounds hilarious now, but it was a big deal at the time, because flares were in and you had to have your hair parted in the middle.

Thunderstick: The mask came about because most drummers were faceless. They were hidden behind kits. So I thought: “I’ll create a faceless drummer.” I couldn’t give it a name of Barry Graham Purkis, because then it would be a bit rubbish. So that’s how Thunderstick came about.

Even the stuffed shirts at the BBC couldn’t ignore the musical shifts that were happening. In November 1978, Radio 1 launched The Friday Rock Show, presented by gravel-voiced DJ Tommy Vance. Airing at 10pm every Friday, it was essential listening for any self-regarding rock fan who wanted to hear the lastet cutting-edge band.

Tony Wilson (Friday Rock Show producer): Alan Freeman had been presenting the Saturday Rock Show on Radio 1 since 1973, but they decided that Fluff was too old for the job, and he left and went off to Capital Radio. I said: “Well, we need to find somebody else to do another rock show.” I decided that Tommy Vance was the best option, against the better judgment of Derek Chinnery, the controller of Radio 1.

Joe Elliott: At the time, there were local radio stations that had their own rock show. But this was the only one on national radio. So when you tuned in to listen to Tommy, you knew you were in for an education.

Tommy Vance (speaking in 2002): The overriding memory of the Rock Show was that I was working for an audience that appreciated it, they liked it and were grateful for the fact I liked it and wanted to play it. But it wasn’t just me, because I had a superb producer, Tony Wilson.

Tony Wilson: I had completely free rein, because nobody in the management knew or cared what we were doing. They were just happy to have someone who was interested enough to do something like that, as long as we didn’t cause any outrage.

Tony Wilson: People say it was quite influential. We did get large mailbags of post every week, and that was an indicator that people were listening. I think it was one of the ways for people to hear music and engage with the new rock movement, and they did.

Joe Elliott: He may not be regarded as an innovator in the same way as, say, John Peel, but for all rock fans in Britain at the time [Tommy Vance’s] show was massively important. He’s never been replaced, and he never can be.

Across the country, things were beginning to heat up. Aside from the release of Def Leppard’s debut EP, 1979 saw the glorious one-two of Motörhead’s Overkill and Bomber, as well as the debut album from Saxon.

Fast Eddie Clarke: We didn’t know we were making these great albums at the time, but we loved ’em to bits. Overkill was absolutely fantastic. We got a new lease of life, and it continued into Bomber. We were just fucking cooking like fuck.

Biff Byford: It really took us by surprise, how popular we became very quickly.

Neal Kay: Probably the most significant gig I did at The Music Machine was when I put Samson, Iron Maiden and Angel Witch on in May 1979.

Thunderstick: When we played The Music Machine for the very first time, I couldn’t believe the amount of people that came through the door. Some of the fans had been laying in wait, waiting for punk to run its course. Once they had done, they came up and pledged allegiance to the New Wave Of British Heavy Metal.

Geoff Barton (writing in Sounds): “The band, dressed in cheesecloth shirts and loon pants, tossed their long hair, pouted, posed and punched their firsts into the air after each agonising guitar solo.”

Alan Lewis (editor, Sounds): I coined NWOBHM (New Wave Of British Heavy Metal) as a front-page headline. But it was sort of an in-joke. We were always hailing something or other as ‘The New Wave Of…’

Thunderstick: I got the front cover of Sounds, with that edition where the phrase The New Wave Of British Heavy Metal was coined.

Biff Byford: We kept getting little reviews in Sounds and Melody Maker. They kept doing little reviews about us. But it really started to happen when Geoff Barton came to see us and a did a huge two-page piece on us in Sounds.

Bruce Dickinson (Samson): NWOBHM was a fiction, really, an invention of Geoff Barton and Sounds. It was a cunning ruse to boost circulation. Having said that, it did represent a lot of bands that were utterly ignored by the mainstream media. Because of that it became real and people got behind it.

Brian Tatler: After the Sounds piece, you suddenly thought: “Okay, there’s other bands around the country doing what we’re doing, they’re the same age.” We end up travelling to Leeds or Newcastle or London. Suddenly our horizons were opened.

Thanks to the business acumen of their new manager, Rod Smallwood, Iron Maiden were jostling with Def Leppard for the position of the NWOBHM’s top dogs.

Ashley Goodall: I think you have to differentiate between Def Leppard and Iron Maiden. Def Leppard had a more American angle; Maiden had a punk ethos about them, though the were definitely a rock band. They had that street-y, London attitude.

Paul Di’Anno (Iron Maiden, speaking in 1980): We still want to stay as close as possible to the kids who got us up here in the first place. I don’t want people to start muttering: “Oh look, there’s so-and-so from Iron Maiden there. Shall we talk to him, or shan’t we?” Bollocks. They should be able to come over and say: “Hello mate, how is it? I thought you played like a c**t the other night.”

Ashley Goodall: I first saw Maiden at the Swan in Hammersmith. It was like a football crowd. They had a hard-core following with the T-shirts. I thought: “This is a great gig. There’s something here that’s really good.”

Bruce Dickinson: It was blindingly obvious that Maiden were going to be massive. This hyper-kinetic band, it was really a force of nature. Paul Di’Anno, he was okay, but I thought: “I could really do something with that band!”

Ashley Goodall: Iron Maiden stood out because they’d taken on some of the punk ethos, which was to do your own thing, put your own record out, make your own life. Maybe they borrowed some of that from the punk bands.

Steve Harris: We decided to release The Soundhouse Tapes (in November 1979) because we’d do really well at gigs, then afterwards there’d be all these fans asking where they could buy one of our records. When we told them there wasn’t any yet they couldn’t believe it. They’d seen the charts in Sounds and assumed we must already have a record deal of some kind, but we didn’t. And I think that’s when we really got the idea of putting the demo out as an actual record.

By the end of 1979 and into 1980, the NWOBHM gathered pace. Every week, a new single appeared from some hitherto unknown band, released on an independent label such as Heavy Metal Records, Bronze or Newcastle’s Neat Records. The scene’s big guns weren’t resting on their laurels, either – Def Leppard and Iron Maiden both released their debut albums, On Through The Night and Iron Maiden, in 1980, while Saxon released two stone-cold classics in the shape of Wheels Of Steel and Strong Arm Of The Law. And then there was Metal For Muthas, a compilation-cum-lightning rod of this new wave of bands.

Joe Elliott: We had the time of our lives making On Through The Night. We were such young kids – Rick Allen was fifteen, I was nineteen – and we were recording our first album at Tittenhurst Park, where John Lennon lived before he sold it to Ringo. And I drew the long straw – I got Lennon’s old bedroom. The view was amazing.

Biff Byford: 1980 was a big year for us and for the heavy metal genre in general. Everything was just right. There was a massive groundswell and a lot of young fans were getting into metal.

Joe Elliott: On Through The Night did pretty well for us. We sold out Sheffield City Hall, it went Top 20 in the UK. But we were a work in progress. Compared to the first Boston album, the first Zeppelin album, the first Van Halen album, it’s Wycombe Wanderers to their Chelsea.

Ashley Goodall: There was a studio in EMI that wasn’t too expensive, so I thought why don’t we get everybody in there and do a good, rough-and-ready compilation of what’s going on at the moment? Basically, aggregate what’s going on and make a statement. That was Metal For Muthas.

Andy Dawson: I remember seeing Iron Maiden at our local theatre on the Metal For Muthas tour. It was the first time I remember seeing an unknown band, and they nailed it. They came on stage looking and acting like they were already successful. I’d never seen that level of confidence before.

Inevitably, the Top 20 success of Def Leppard and Iron Maiden spurred the interest of the other big labels. All around the country at the gigs, the denim-clad crowds were peppered with A&R representatives.

Jess Cox: Everybody wanted their New Wave Of British Heavy Metal band. All of a sudden these major labels started to appear. I remember playing Sunderland Mecca on a Friday night, and the head of labels from Virgin, EMI and CBS had flown up.

Andy Dawson: It wasn’t like the major labels all swept in and started pumping money. That happened for a few bands, but the rest of us were just working our arses off trying to make this happen.

Jess Cox: The guy we had managing us at the time said: “MCA want to sign you. It means you get your rent paid and six pounds a week.” We were, like: “Whoah, that sounds good. Yeah, we’ll do that.”

Andy Dawson: There were a few bands that made the jump to a major, like Saxon and Iron Maiden and Def Leppard obviously. But for the majority it felt like an independent scene. That was the beauty of it – it wasn’t contrived or controlled by a record company executive saying: “This is what you need to do.”

Bruce Dickinson: In Samson we only ever had about thirty quid a week out of the band. But we were bonkers, completely out of our gourds, and we’d signed the document.

Jess Cox: In the Tygers we didn’t have two pennies to rub together. We’d kip on floors or wherever we could find.

While the music industry turned its beady eye on the NWOBHM scene, the bands themselves were treating each other with as much suspicion as they were camaraderie.

Brian Tatler: I think there was a rivalry. Because, of course, we’re all trying to make it, and you don’t want somebody else to step on you.

Joe Elliott: We didn’t ask to be included in the New Wave Of British Heavy Metal, we were just told we were in it. We were happy to take the press, but the fact that it kept coming with this NWOBHM typecast, it became more of a “What the hell is this?” thing.

Jess Cox: It wasn’t this great big family. Bands were starting to go: “Hold on, there are too many other bands, we’re not getting attention.” But we did get quite friendly with Maiden.

Brian Tatler: You’d go and check the competition: Angel Witch, Samson, Maiden, the Leps, Saxon. We’d meet them occasionally, but it was a bit insular. We’d judge everything: “Are they good? Can we learn from them? Can we steal from them?”

Fast Eddie Clarke: We didn’t mix with Thin Lizzy or Judas Priest or that lot. The other bands didn’t want to talk to us. We weren’t looked on as musicians.

Biff Byford: To tell you the truth, we were so fucking busy that we didn’t have much chance to look at what everybody else was doing.

Fast Eddie Clarke: We did notice Iron Maiden. Our paths crossed, but they were a bit stand-offish. There was still this thing that Motörhead were this loud, antisocial juggernaut. And people were scared of us because of our Hells Angels contacts.

Joe Elliott: At one gig, I went on stage in a pair of bright red trousers, and a white shirt covered in hearts. That was me going: “I’m not fucking wearing a leather jacket and jeans like every other bastard band in this movement that we don’t think we’re in anyway.”

Jess Cox: We went to London to do some shows with Maiden at the Marquee, then all of a sudden bands started coming to see us. Judas Priest turned up at one gig. Gary Moore got up on stage and bloody played with us.

Unlike punk, there was no generational divide here. The new breed of metal bands viewed the bands that came before with reverence, while the original masters were curious to see what they’d inspired.

Andy Dawson: You wanted to emulate these bands, not kill them off. Bands like Rainbow were still massive. Everybody still loved then. When you went to a rock disco, you’d still hear stuff like that.

Ashley Goodall: Ozzy Osbourne turned up to see Maiden at one of the early gigs at the Music Machine, so there was a lot of interest in the new generation of bands.

Rob Halford: We went out with Iron Maiden, Def Leppard. It’s what you should do, no matter who you are or what music you play. We’re all on the same journey. We’ve all been through barely affording gas and sleeping in the van. That’s part of your apprenticeship.

KK Downing: I’d never heard of Iron Maiden until someone told me that they were going to support us on the British Steel tour. Then they started to get mouthy in the press, saying they were going to blow the bollocks off Judas Priest and all this sort of stuff. I said: “I appreciate the attitude, like, but let’s fuck ’em off and get somebody who appreciates us!” But they did it and it was fine. I’m glad that they emerged and became a force to be reckoned with, and gained their own identity, musically, visually and in every way possible.

Judas Priest themselves were the bridge between the old guard and the new wave. Their debut album, Rocka Rolla, had come out in 1974, when many of the NWOBHM musicians were still at school, and they’d survived the punk wars largely unscathed. Their sixth album, British Steel, was released in April 1980, as the movement began to broaden.

Rob Halford: The title of the album was a statement in itself. Sheffield steel was the inspiration for British Steel. And we should all be proud that British musicians are responsible for this force in music called heavy metal.

KK Downing: We’d made a few albums by then. We weren’t exactly floundering around, but everything did lock in with British Steel: the artwork, the songs, the stage clothes. Everything consolidated who we were and where we were going. It was almost like a rebel’s almanac.

Rob Halford: There was a lot of crap going down in the UK. Margaret Thatcher had been in power for quite a number of years. The recession was going on, people had no jobs and no money. Everything the government had said they were going to try to do was just a crock of shit, and people were pushing back. All of that’s in there, you know: ‘Completely wasted, out of work and down’ – no one cares, I’m going to break the law. We weren’t giving people affirmation to break the law, but we could understand their frustration.

Andy Dawson: I think a lot of energy in the NWOBHM was frustration. It was the start of the Thatcher era, which was quite destructive.

If there was one event that acted as a lightning rod for British rock – not just NWOBHM, but all of it – then it was the inaugural Monsters Of Rock festival held at the Donington Park racetrack in Castle Donington, Leicestershire on August 16, 1980. The braindchild of young promoter Paul Loasby and his business partner Maurice Jones, the first line‑up featured Rainbow as headliners, supported by Judas Priest, Scorpions, April Wine, Saxon, Riot and Touch. There had been other outdoor events before, but this was the only one dedicated solely to heavy music.

Rob Halford: We were very aware that it was the first festival of its type in the UK and was a major event in that respect. All the festivals that had happened in the UK before had had a cross-section of bands, so this was the first to go with specifically one type of music. Our reaction when we first heard about it was that we’d like to give it a crack.

Biff Byford: When they asked us to play Monsters Of Rock we had no fucking idea what it was.

Paul Loasby (Monsters Of Rock promoter): The amount of rain was unbelievable. I’d borrowed money personally to put on this show. And the night before, at four in the morning when a monsoon is coming down in Castle Donington, I’m sitting there with a bottle of Scotch in my hand thinking: “This is the ultimate, the biggest disaster in the history of rock’n’roll and I’m going to lose everything.” Not that I had anything, but I was going to lose it anyway.

Neal Kay: I compered the gig. I was nervous – I’ve never faced a crowd that big before. But when I walked out on that huge stage, the first ten rows were all Soundhouse members.

Biff Byford: When we walked on that stage we’d done a hundred thousand records. I would imagine that ninety-nine per cent of the people in that audience had got Wheels Of Steel. So it was fantastic for us. It was our first festival gig, the first time we’d played to an audience of over three thousand. The roar when we went out on stage was incredible. When I walked off I thought: “Follow that.” That was a fucking great gig.

Neal Kay: The atmosphere was fantastic. There were campfires about twilight time.

Biff Byford: This was the new generation of heavy metal. This was our music – fucking have it!

After so many years in the doldrums, British rock now seemed unstoppable. And then in 1981 the unthinkable happened when those perpetual outcasts Motörhead managed to reached No.1 in the UK chart with their steel-plated live album, No Sleep ’Til Hammersmith.

Fast Eddie Clarke: I suppose having a number one record got us a bit of respect. I can’t remember who we went to see, but David Coverdale was there and he said: “Let me buy you a drink, guys.” And I’m thinking: “Fuck me, that’s unheard of.”

Jess Cox: It was only years later that I realised how many of these bands there were.

Biff Byford: You’ve got Judas Priest, you’ve got Motörhead, you’ve got Saxon, you’ve got Maiden… it was endless.

Ashley Goodall: It became clear very quickly who the leaders were. Leppard were slightly ahead in a way, but it did kind of blow out a bit by eighty-one. Once Maiden were away it was a completely different game.

Jess Cox: Iron Maiden and Def Leppard had people behind them in the know. They knew how it was all going to pan out.

Ashley Goodall: I’m a believer that if you’re going to be huge, you’re going to be huge. No one else was actually that good.

For the NWOBHM’s leading lights, the next logical step would be to set their sights on America. Def Leppard had seemingly made their intentions clear with the track Hello America on On Through The Night– something that prompted a backlash in Sounds, and saw them bottled at the 1980 Reading Festival for their troubles. The old cliché about Britain hating success stories seemed to ring true, although the fact remained that America was there for the taking – at least for a select few.

Biff Byford: Def Leppard went off and did a different thing. They went down the American route.

Rick Savage (Def Leppard): Hello America? I swear to God, we really weren’t that intelligent. It was the lyrics of a kid fantasising. I can see how people read into it, but it was way more innocent than that, way more naive.

Joe Elliott: The legend about us getting bottled off at Reading 1980 is a myth, really. We probably had six or seven bottles of piss thrown up, and maybe a tomato, but it didn’t put us off. That ‘backlash’ was all blown out of proportion. We’re living proof that bad reviews make no difference.

Fast Eddie Clarke: We didn’t think: “We want to break America.” We didn’t have any delusions of grandeur. No fucker over there would touch us anyway.

Joe Elliott: Iron Maiden had been to America a month before us. I didn’t see them getting any flak. Nor should they have. So why the hell did we?

Steve Harris: We were never obsessed with breaking America. We always planned to come out here and give everything we’d got, and they’d either like it or they wouldn’t. Fortunately for us they liked it. In fact they bloody loved it. But it was always a challenge. We didn’t do things the normal way.

Glenn Tipton (Judas Priest): If we hadn’t gone to America we would probably only have lasted for another three or four years.

Rob Halford: We were definitely aware of what was going on with MTV [which launched in August 1981]. It was a game changer.

Joe Elliott: The fledging MTV, having nothing to play, liked the idea of this young UK rock band, so they picked up on Bringin’ On The Heartbreak [from Leppard’s second album, 1981’s High ’n’ Dry]. So six months, maybe a year after High ’n’ Dry came out, we started getting these telexes saying: “Your album is selling six thousand copies a week. Then it was ten, fifteen, twenty thousand copies a week. It was heading toward platinum by the time we had Pyromania in the bag.

Throughout 1982 and into 1983, the stream of bands releasing singles and albums didn’t abate. To the casual observer, the British rock and metal scene looked in rude health. But in reality it was starting to run on fumes. Thanks to Def Leppard and Iron Maiden’s Stateside success, America was waking up to what was happening across the Atlantic. And it wanted a piece of the action.

Andy Dawson: By 1983, when Savage finally released our first album, it seemed like the British scene was beginning to peter out.

Brian Tatler: A lot of the New Wave Of British Heavy Metal bands had given up, split up, been dropped – including Diamond Head. The attention had gone onto the American bands. It was a tough period for a lot of British bands.

Rob Halford: Once the Americans got hold of this thing coming from Britain and took it into their own kind of style and approach, everything went global.

Fast Eddie Clarke: I remember going to LA with the first Fastway album and hearing about Mötley Crüe. They were calling them ‘the LA Motörhead’.

Biff Byford: We supported Mötley Crüe. They loved us so much they invited us out on their first tour. It was a great tour.

Andy Dawson: When we did our first Kerrang! interview, the journalist, Xavier Russell, was banging on about how much this band called Metallica loved Savage. And we were like: “Who?”

Fast Eddie Clarke: Motörhead were two years too early. I was fucking surprised when it all kicked in with Metallica and that lot. They were playing exactly what we were playing, and doing fantastic business.

Def Leppard’s Pyromania and Judas Priest’s Screaming For Vengeance were huge hits in America, but at home the New Wave Of British Heavy Metal scene was rapidly deflating. By the end of that year it was all over bar the shouting.

Nearly four decades on, the legacy of the British bands of the late 70s and early 80s remains as strong as ever. The more obvious success stories of that golden era – Maiden, Leppard, Saxon, Motörhead – speak for themselves. But the ambition, independence and energy of the period mark it out as the last time British rock and metal truly punched above its weight on the world stage.

Biff Byford: It was a hugely important era. Massively important.

Jess Cox: People look back and see the wonderful naivety and innocence of it.

Andy Dawson: I don’t think any of us realised we were part of something new. We were emulating something that we loved that was already there. But because we were young and innocent and a bit stupid, it brought something new to it.

Fast Eddie Clarke: Maybe we did change things. We certainly changed things from the way they were in the early seventies.

Ashley Goodall: Heavy rock music had been out of favour for about five years, and bands like Maiden gave it a kick. It made it cool to be into it again. It was okay to be a heavy rocker again.

Brian Tatler: I really think it was an important time for British music. It helped keep rock going. Just look at how amazingly Iron Maiden have done over the last forty years. Everything would sound different without the New Wave Of British Heavy Metal.

Bruce Dickinson: Years ago, someone asked: “What’s the secret of Maiden’s success?” I said:“I wish it was complicated, but it’s just: don’t let people down.” Don’t let people down. I can live with that on my headstone.

Steve Harris: We always stuck at what we believed in. I’m proud of that.

Biff Byford: We were singing songs for that generation about motorcycles and women and having a great time. People just loved it, really.

Andy Dawson: People have kept a real love of that time, and are looking for more of it. I’m sure they’d love to see younger bands. It would be great to see a bunch of eighteen- or nineteen-year-olds coming out, doing something like that, with that kind of energy. It would be a fresh kick up the arse.

Biff Byford: It was very British, but it shot round the fucking world. It changed music.

The main players in the birth of the NWOBHM

Geoff Barton - Legendary Sounds (and current Classic Rock) journalist. The first person to use the phrase ‘New Wave Of British Heavy Metal’ in print.

Biff Byford - Barnsley-born Saxon singer. Has fronted the band since they formed as Son Of A Bitch in the mid-70s.

Fast Eddie Clarke - Former Motörhead guitarist and sole surviving member of the classic line-up. Formed Fastway after his departure in 1982.

Jess Cox - Original singer with Whitley Bay NWOBHM pioneers the Tygers Of Pan Tang. Resurrected groundbreaking label Neat Records in the early 90s.

Andy Dawson - Guitarist with Mansfield band Savage, whose track Let It Loose was covered by Metallica on an early demo.

Bruce Dickinson - Leather-lunged former Samson singer (also known as Bruce Bruce). Later replaced Paul Di’Anno in Iron Maiden.

KK Downing - Long-time Judas Priest guitarist. Left the band in 2011 and has since opened a golf course.

Joe Elliott - Singer and founder member of Def Leppard, the first of the NWOBHM bands to make it big in America.

Ashley Goodall - Former EMI Records A&R man. Signed Iron Maiden and helped put together the groundbreaking Metal For Muthas compilation.

Rob Halford - Judas Priest singer, and the man who helped give metal its iconic leather uniform.

Steve Harris - Founder and driving force behind Iron Maiden, the most successful NWOBHM band of them all.

Neal Kay - DJ, tastemaker, compere and founder of legendary north London rock mecca the Heavy Metal Soundhouse.

Rick Savage - Def Leppard bassist and founder member.

Brian Tatler - Guitarist and founder of Diamond Head, whose self-released Lightning To The Nations album was one of the NWOBHM’s early successes.

Thunderstick - Also known as Barry Graham Purkis, ski-masked former Samson (and, briefly, Iron Maiden) drummer. New album Something Wicked This Way Comes is out soon.

Tommy Vance - Late Radio 1 DJ and presenter of Radio 1’s The Friday Rock Show. AKA The Voice Of Rock.

Tony Wilson - Creator and producer of The Friday Rock Show.

Dave Everley has been writing about and occasionally humming along to music since the early 90s. During that time, he has been Deputy Editor on Kerrang! and Classic Rock, Associate Editor on Q magazine and staff writer/tea boy on Raw, not necessarily in that order. He has written for Metal Hammer, Louder, Prog, the Observer, Select, Mojo, the Evening Standard and the totally legendary Ultrakill. He is still waiting for Billy Gibbons to send him a bottle of hot sauce he was promised several years ago.