It’s no exaggeration to say that the passing of B.B. King marks the end of an era in modern music. For the man born Riley B King in 1925 was the last of the generation of blues artists that forged the music in the Southern States prior to World War Two. There’s still Buddy Guy, of course, but King was the last link back to that primordial scene, which in rock’n’roll terms represents the dawn of creation. His was a life that, in the words of long time friend Bonnie Raitt, “encapsulated the history of the African-American experience in America post slavery… as well as the whole history of rock’n’roll, jazz and blues.”

King lived the life of a bluesman, right down to learning his craft playing on street corners. Indeed, written down on a page his early years almost read like a spoof of the hardship and suffering we traditionally associate with the blues. Born into a sharecropping family whose eldest members could remember slavery, his father left when he was 5 and his mother died when he was 10. From that age Riley had to fend for himself, experiencing the sort of poverty that from the distance of the early 21st Century is unimaginable.

Needless to say, music was a consolation. “The blues didn’t have to explain the mystery of the pain that I felt, it was there in the songs,” King wrote years later in his autobiography Blues All Around Me. Growing up it was the music of Blind Lemon Jefferson and T Bone Walker that comforted, sustained and inspired him. At the age of 12, he bought his first guitar.

And it is as a guitarist that he made his name. His developed a unique style - deft and economic phrasing with ‘bent’ notes and a clear, bright tone that he coaxed from his Gibson ES 355, one of over 30 guitars that were christened Lucille. The name came from an incident in the winter of 1949 when King played a bar in the town of Twist, Arkansas. Whilst he was performing two men who were fighting knocked over a pail of kerosene and the venue went up in flames. King rushed back inside to rescue his instrument, grabbed it and later overheard that the fight had been over a woman called Lucille. His lucky guitar was nicknamed thus.

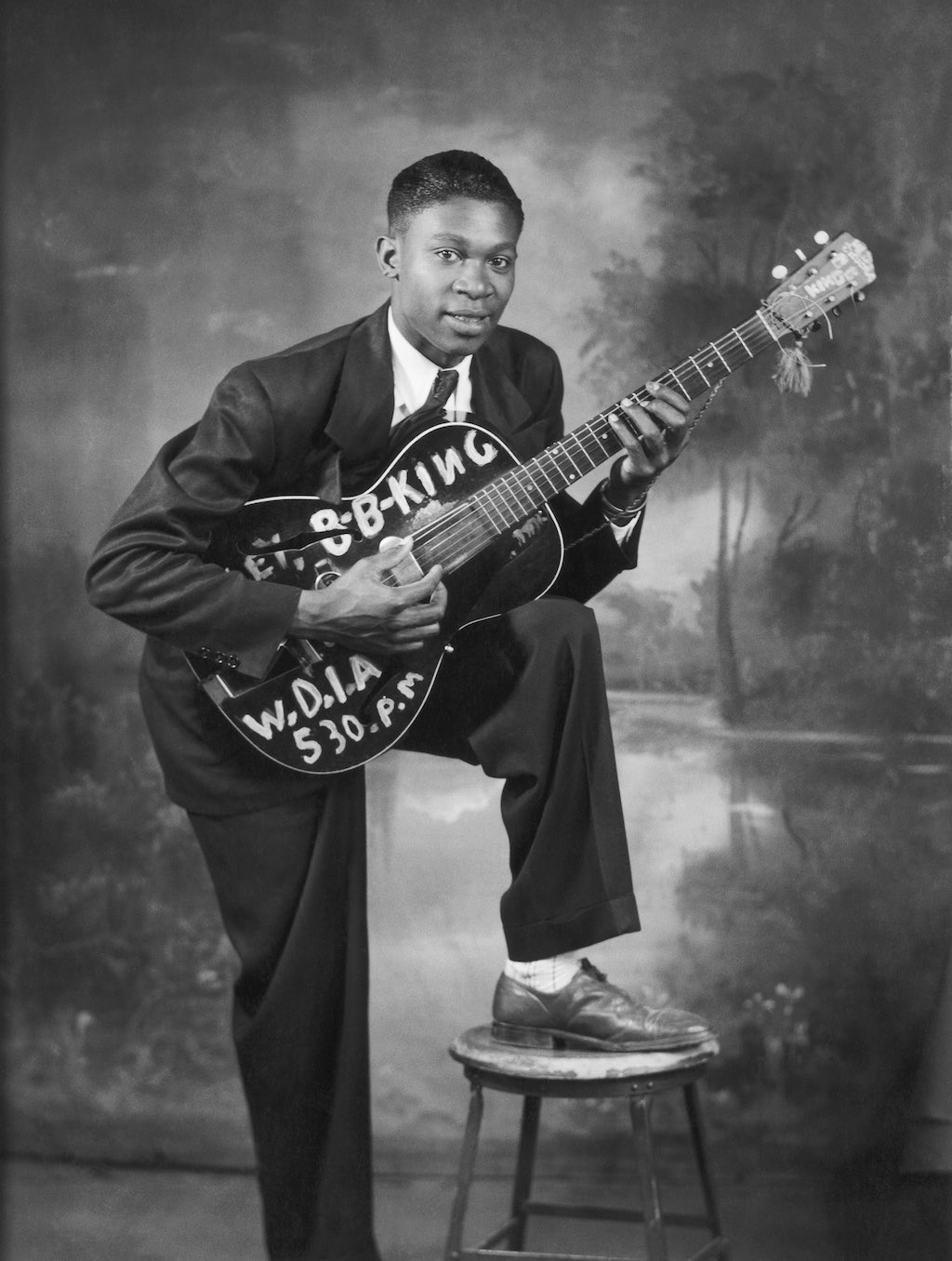

B.B. King at segregated Memphis radio station WDIA in 1949, where he had a daily 15-minute show. Pic: Getty Images

King’s rise came just before rock n’ roll and though he knew many of its original instigators – he recorded for Sun and Ike Turner recommended him to the LA-based label Modern Records – he didn’t benefit directly from its revolution. Instead he kept his head down and remained on the so-called chitlin circuit that had so far sustained him. King was just two years the senior of Chuck Berry, but seemed a generation older. He lacked a gimmick, none of his songs had the hooks or easy going slang that appealed to teenagers. As the 50s shaded into the 60s he was barely keeping his head above water and was being hounded by the IRS for unpaid taxes. “I didn’t know what I was doing,” he said of these years, “I didn’t know you could hire a tax attorney to work out a deal. I just went on, putting one foot in front of the another, plodding my way through.”

It wasn’t until the late 60s that he started to receive the respect and rewards he deserved. In common with contemporaries like Howlin’ Wolf and Muddy Waters it took a generation of young British musicians to alert a wider audience to his music. His 1965 album Live At The Regal — perhaps the greatest live blues record — was a huge influence on Eric Clapton, Mick Taylor and Peter Green, while John Lennon opined that “he wished (he) could play guitar like BB King.” He toured with the Stones and then in 1970 scored a surprise hit with The Thrill Has Gone. It won him his first Grammy and set him up for the sort of crossover success that had scarcely seemed possible just a few years earlier.

King became revered not just for his superb guitar playing, but for what he represented. As the years went by and older bluesmen fell by the wayside, he continued to work, at a feverish rate. At his peak he was playing over 340 shows a year, a figure which by his 70s had slowed down to a mere 200 or so. He toured the Soviet Union long before the Cold War thawed, and then in 1988 collaborated with U2 on their Rattle And Hum project. The following year their album track When Love Comes To Town became his only UK hit single.

There was a certain cultural tourism in all this and King must have been aware that the longer he continued, the more he became a living monument to the blues. But after the decades he spent struggling to make ends meet he surely didn’t begrudge the ambassadorial role he took on for the music he loved so much. There aren’t many left now who remember first hand the conditions and deprivation that provided so much of its source material - as an unnamed contributor to the 2011 Life Of Riley feature documentary sagely put it: “the blues won’t stop (when he goes), but it’ll never be the same.”

B.B. KING SEPTEMBER 16 1925 – MAY 14 2015

Related News: B.B. King dead at 89 - Last King Of The Blues passes away in his sleep.