Yesterday’s news story concerning Robert John Godfrey’s retirement from The Enid, with added sideswipe at modern day progressive rock and some of the musicians that make it had barely gone live on the Prog website when the first of many responses arrived through the ether.

“I’m afraid,” it said, “that Robert John Godfrey is taking out of his arse. What utter tripe.”. Given one of the main targets of Godfrey’s ire was current progressive wunderkind Steven Wilson, the sentiment of the original reaction was one that was by and large, echoed throughout the torrent of responses that flooded Prog’s Facebook and Twitter feeds, our website and extended out and across the online prog fraternity.

The whole scenario raises one or two interesting points – the most obvious of which is does Robert John Godfrey have a point? And if he does, were his points of reference correct in relation to that. And ultimately, does it really matter? On this latter point my personal feeling is not really. The history of rock music is littered with verbal spats between artists, most adding a soupçon of enjoyment to the crazy world of rock’n’roll for a short while, but few, if any, leaving any lasting effects on the careers of the protagonists or remaining embedded in the memory of all but the most zealous fan.

Godfrey’s words that have caused such consternation among prog fans were: “The thing that pisses me off so much about the prog scene is that it is all about muso rock. It’s all about people like Steven Wilson who possess all the talent and all the production genius – and has made a great name for himself – but who offer absolutely no content that is memorable or meaningful.” He followed these with some some rose-tinted commentary about the era in which The Enid and he himself developed as a musician of note: “The early 70s blossomed in terms of film, in terms of fashion and progressiveness was a movement”, before adding the further barbed “Now prog is just bog. Most of it is now meaningless, shallow nonsense. It is either a poor parody of things gone past or is a cynical attempt to try and feed the prog community with the sort of stuff they are used to. Now we have nothing challenging, no new ideas and nothing behind it. The Enid are different from that.”

So the main charges appear to be that A) modern day prog is a poor third of fourth cousin to the originators of forty years ago and B) Steven Wilson might be a production whizz kid but his music sucks. I’ll ignore the “muso rock” allegations, largely because Godfrey himself is part of a scene that revels in the prodigy of musicians.

OK, well how you feel about how progressive music sounds today will by and large depend on how you view progressive music overall. Prog, much like heavy metal, is a multi-faceted genre these days and the fans of each sub-genre are as defiant about the merits of their chosen sound against others as ever. Certain sub-genres are more reminiscent of the classic 70s sounding progressive music that I suspect Godfrey is referring to. Back in the day, this was an argument levelled at the 80s era of progressive bands who gave rise to neo-prog. All admitted to a certain level of influence – I think it was Mark Kelly who once told me, tongue-in-cheek, that Marillion should have been sued over the similarities between Grendel and Supper’s Ready – but like many developing bands, they started by trying to emulate their heroes before developing their own sounds. Some of those sounds strayed far from the original template, others less so. But the point is, that in the 1980s, those were the only reference points available. But just because the original progressive bands were creating something sonically new doesn’t mean they too did not emulate those who’d inspired them. In the very latest issue of Prog, Phil Collins recalls writing Los Endos, stating, “I’d heard the Santana album Borboletta and there’s a tune on it called Promise Of A Fisherman. If you’ve got it on your iPod, have a listen and think of Los Endos. That’s where it came from.”

But progressive music in 2016 is vastly different from 1984. Of course there are bands that prefer to remain sonically in thrall to their heroes, but equally progressive music now operates under such an expansive umbrella that it far outstrips the kind of withering put down Mr. Godfrey conjures up. The very latest issue of Prog features a myriad of differing musical styles, from the traditional sounds of Genesis, the awkward jazz fusion of Brand X, the modern progressive metal approach of Headspace, the Krautrock-inspired muse of Michael Rother, the Floydian grandeur of Andy Jackson, the art prog of Ulver, the epic rock of Kiama, the modern US progressive approach of Shearwater, the conceptual drive of Alan Parson and beyond. True, we’ll have some grumbling from those who might state that in their eyes, some of these artists aren’t progressive, but for every one of those, there will be a reader rejoicing in the inclusion of a favoured artist.

It is, to a certain extent, a very lazy argument, similar to the one I hear (fortunately less frequently these days) that all prog sounds the same. Really? Even back in the day Genesis never sounded like Yes. Who never sounded like King Crimson. Who never sounded like Jethro Tull. Who never sounded like ELP. Who never sounded like Pink Floyd. I could go on, but I think you get my point. And perhaps Mr. Godfrey would be wise to remember that I’ve heard it say many Enid albums sound remarkable similar to the casual listener!

Had Godfrey made this claim twenty years ago, he might have had a bit of a point. In an era where it is progressive music’s diversity that is it’s strength, it’s a weak condemnation. Not wholly without foundation, but weak nonetheless. And becoming increasingly weaker.

As for his diatribe against Steven Wilson, well, as one office wag put it, that’s a bit like Dumbeldore kicking Harry Potter. True, Steven Wilson does have his detractors. We know, they tend to accuse us of putting him in every issue (some even on every cover – although Christ alone knows which magazine retailers they go to), even if we go several months without mentioning his very name. And whilst it is perfectly acceptable for people to voice their opinion if they don’t like Steven’s music, one can’t help feeling that it is Wilson’s own ubiquity, general profundity, prolific nature and level of success that gets up the noses of a certain section of the prog audience. There is a reason for Wilson’s success and it has as much to do with hard graft as it does natural talent. And where the two align so well, it is little wonder the rewards are so palpable. It is only natural a certain amount of envy of others goes with the territory.

Godfrey does highlight Wilson’s achievements in the studio. Although with such an impressive array of work for the likes of King Crimson, Yes, Gentle Giant, Jethro Tull, XTC, Simple Minds and beyond under his belt, to criticize the work of a man entrusted by such a spread of artists reminds me of that legendary Mark Twain quote: it is better to keep your mouth shut and let people think you’re a fool rather than open it and remove all doubt. Interesting to note one member of Classic Rock stated, when discussing this current furore, that maybe one or two of the thinner-sounding Enid albums might have benefitted from Wilson’s production nous!

As for sticking the boot into Wilson’s musical endeavors? Unfortunately here’s where things really do begin to smack of sour grapes. After all, we’re not just talking about a solo career where every album has sounded different to its predecessor. We’re talking about the Grammy-winning career of Porcupine Tree, who travelled from early progenitors of psychedelic prog into the prog metal behemoths pre hiatus, the wistful art rock of No-man, the experimental dark pop prog of Blackfield and the drone-infused Bass Communion. To suggest nothing in such a body of work contains anything approaching “memorable or meaningful” is to do the exact opposite of that which Mark Twain was suggesting.

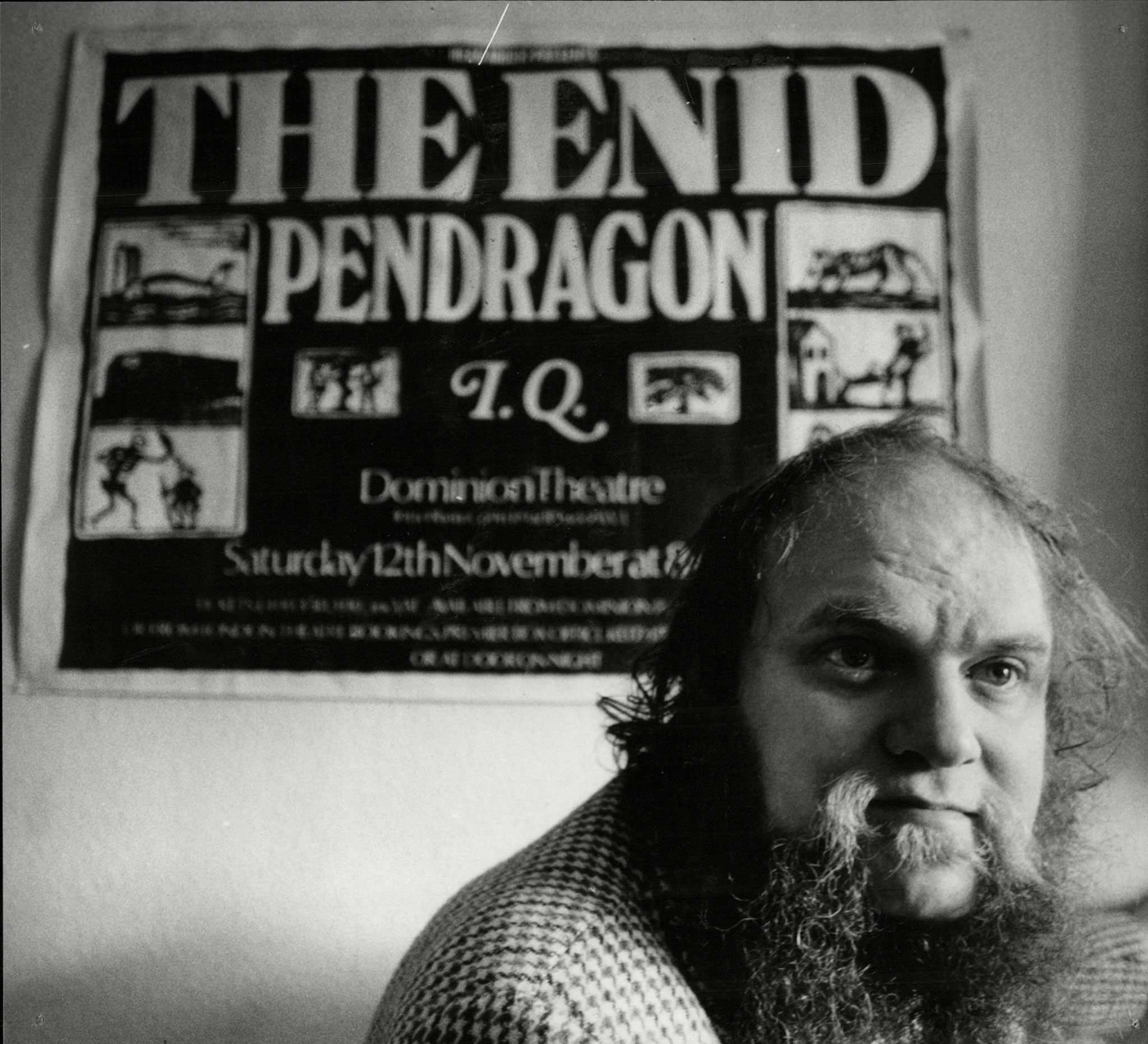

But of course Godfrey has form in this area. In the past Barclay James Harvest, with whom he worked in the early days, and Marillion, have been targets of his ire. The former the result of a bitter and rancorous legal battle (of which Godfrey is, of course, no stranger). The latter? Who knows? Maybe RJG was looking for a bit of extra publicity? Let’s not forget that Wilson himself has history here too. Back in the fourth issue of Classic Rock magazine he let rip at bands like IQ, Pallas and Pendragon, saying “It’s abysmal, awful. It’s a total contradiction in terms to call it progressive. Most of it is not very well done. Its bereft of ideas, it’s bereft of inspiration. I can’t damn it enough really.” Well, thank God the a lot of that music has developed over the ensuing twenty years, even if the arguments have not!

To be honest, I know both of these artists well, and like both very much as people as well as musicians. Steven has since told me how he came to regret that comment, but it was made in a different time, when he railed against the prog label because, as he would later tell the DPRP website, “What you have to understand about that and put into context is that the whole idea about what is progressive rock has changed almost beyond recognition in the last twelve years, probably since the turn of the millennium. Aligning yourself with progressive rock at that time was a very, very dangerous game to play, but it isn’t any more. Maybe that sounds like some kind of careerist thing and perhaps it was, but it wasn’t a consciously careerist thing.”

Equally, I can’t help thinking that Robert is just having a good old grumble because, well, he hasn’t for a while, and The Enid have a new album out. It also coincides with the fact he is retiring due to ill health. I’m sure, no matter what brave front that has been put on in public, this is a decision which must have been inwardly devastating for such a fiercely proud man and musician. It’s a sideswipe at the younger musicians he leaves behind. And who in turn will undoubtedly let their guard drop in front of a journalist and say something they might later wish they hadn’t.

Here I feel I should point out that Robert has given Prog magazine an interview about his retirement which we will be running online tomorrow (a bigger feature follows in the next issue of the magazine). Here he made similar comments about progressive music and Steven Wilson, but asked that they be “off the record”. It does raise the possibility such a request was ignored when the original story appeared online, although I know for sure neither one way or the other. But it would be awful, for all the anger currently resounding about the Internet (which will have largely dissipated within days, until another similar story featuring someone else gets everyone’s hackles rising again), means that an elegant and talented man is largely told to “bog off”, rather than leave with the platitudes he’s due.