“They knew they had the magic,” photographer Mick Rock says, almost 31 years after he first laid eyes on the callow, unapologetically pretty Queen. “That was firmly imprinted on me. And having told me how good they were, they played me the music – it was Queen II, which they had just finished recording. They asked me to describe it, and I said: ‘It’s Bowie meets Led Zeppelin.’ That was good; they wanted to work with me, but they wanted to know that I got it. They were picky from the get-go. It was trial by chatter...”

Mick Rock can recall that encounter exactly: September 1973, in a meeting set up at Trident studios in London. “Trident was a den of iniquity,” he remembers. “Ziggy Stardust, Transformer and All The Young Dudes were made there. I walked in and they swarmed me like kookaburras. They were confident in the way that Bowie was…”

While Queen were keen to test out Rock, both parties were aware that this photographer’s celebrity exceeded that of the band’s, at least for now. Rock had already shot some of the era’s defining images; he had befriended David Bowie and had photographed him as Ziggy Stardust and made him and glam-rock iconic; he’d shot the cover of Lou Reed’s Transformer album and Iggy & The Stooges’ Raw Power; one of his first jobs had been photographing Syd Barrett for his The Madcap Laughs. In a time when nobody thought any of it was going to last, Rock was where it was at.

“I had a degree in modern languages from Cambridge, and I had an obsession with crazy poets – Shelley, Byron and also the beats, Ferlinghetti, people like that. I aspired to that life – sex and abusive chemicals. I didn’t necessarily want to be a photographer, more a writer or a lyricist. But all that got thrown overboard when the chemicals showed up. I was just playing around with a camera and a young lady and it sort of rolled on from there. Because I was hanging out with hippies and musos – it was: ‘Here’s £10. Can you shoot this?’. You couldn’t make a living at it, but I was interested in the edge; I wanted something that got me excited.

“People had this idea of me, as a result of my association with Bowie and Lou and Iggy… the importance of the image. They believed that I could help get them over, if you like.”

Rock bonded with Queen quickly, especially with Freddie, in whom he saw many of the same qualities as the other showmen he had followed: “There was something slightly otherworldly about them,” Rock explains. “To me they look mythological. I never saw them as inhuman, just more like fantastic creatures, chimaeras in the pre-Raphaelite world. I was soaked in that stuff.”

The first rolls of film that Rock shot became what he now calls The Nudie Sessions. The band, rail-thin and pouty, were stripped to the waist, and “would have looked like a bunch of schoolgirls if they’d had boobies. The other three didn’t quite want it, but Freddie loved it, of course. Those pictures got them their first serious attention, although it was somewhat disparaging. Must have been from the NME – they were in the knocking business.”

Rock then shot the band at their first big London gig, at Imperial College. He was impressed by the large crowd that had turned out, even though the band had sold very few records and rarely appeared in the music papers. “The fans were right up against this little stage, and Freddie was like he was in a stadium already. He had a visionary quality.”

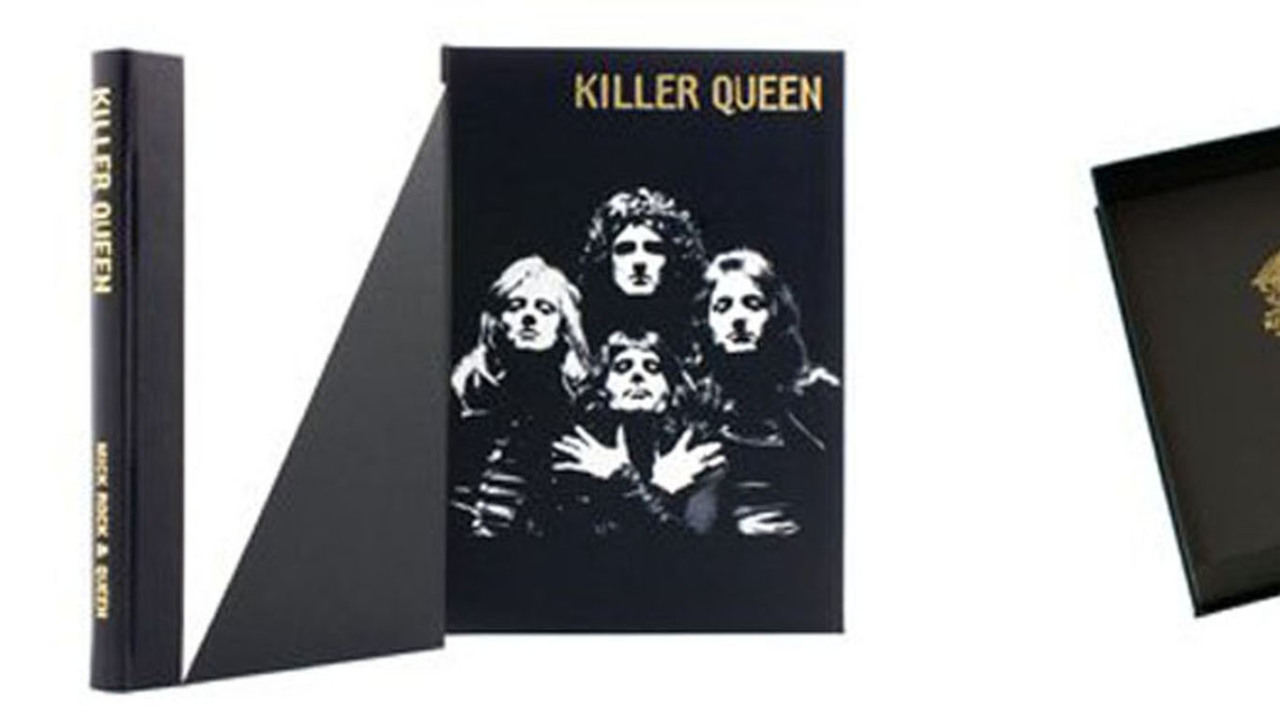

The band asked Rock to design and shoot a cover for the Queen II album. “The brief was that it was to be a gatefold cover – they had wangled that – and the theme was black and white. Around that time I’d got to know John Kobal, who had all of these Hollywood pictures he’d picked up for free on the studio lots. He was making these little books, and he’d done one on Marlene Dietrich. There was this shot of her with her arms crossed, taken on the set of Shanghai Express. I shot some live stuff of Queen up in Manchester, and then I hung out with them afterwards. I showed Freddie this book with the picture, and he said: ‘I shall be Marlene…’.

“We did the ‘black’ shots and then the ‘white’ shots on the same day, and we’d still made no decision as to which we’d go with. We looked at everything, and they picked out two shots, one black, one white, but they couldn’t decide which one would go on the outside cover. Me and Freddie were on the same one, we wanted the black. The other three were more for the white. Freddie badgered them, and the black became the cover. And that shot has haunted them…”

Rock also designed the cover and did the paste-up work himself. “I don’t suppose I got more than 300 quid. If I did I was doing well. In those days you just didn’t see it as this thing that would last in any way. Although thank God that it has.”

Rock worked with Queen until 1975. “By the time we did some of the later pictures, the glammy thing was still there, they were still kind of pretty, but as time went on they were less overtly poofy. But they’d made the statement, they’d got the attention.

“Freddie was fascinating. You know, you wake up 30 years later, and you realise that in the purest terms he had the greatest voice to come out of rock’n’roll. I was very fond of him. We would work with those extraordinary teeth. He had an overbite caused because he had four extra teeth at the back of his mouth. He would never have them removed, though, because he felt that it expanded his palate and if they came out it might interfere with his voice. At first he would have his mouth closed, and I would let him place his lips over his teeth. Later, of course, they became something he was known for.”

Soon after Queen’s Sheer Heart Attack album, Rock went to New York and became embroiled in punk and new wave. Queen recorded Bohemian Rhapsody in the year that punk hit. The paths of the band and the photographer divided.

“I saw a very clear line between art-school rockers and then glam and then punk,” Rock says. “To me they came from the same place, they were evolutions from each other. But something happened. I got lost in the whole thing. I was torrid with chemical toxicity. One became a prisoner of one’s own image. The same thing happened with Lou and Iggy and David.”

There was some post-modern irony in Rock’s physical decline. He had become a victim of the lifestyle that his very own images had helped to set in the minds of those caught up in the culture. He’s thankful to have emerged at the other side – albeit at the cost, seven years ago, of a quadruple heart bypass.

Rock’s photographic catalogue, of which his work with Queen is an important part, is now one of the most iconic and relevant in rock’n’roll history.

“It’s strange,” he says in parting. “There weren’t even that many photographers around. There weren’t that many outlets for these pictures. Not that many photographers were interested in these bands. Quite often, I was the only one there.”

It was everyone’s good luck that he was.

WHITE QUEEN (LIVE AT THE RAINBOW)

MICK ROCK: I went round to shoot a solo session with Roger, probably for a teenie magazine. The idea was ‘Roger at home’. When I got there he’d only just got out of bed. In one picture he has a tea cosy on his head. He was a major prankster.

Maybe Mary [Austin – Freddie’s long-time confidant] brought the clothes along for Freddie’s session, and that’s why she’s in some of the pictures.

Or maybe they simply said to me: “Oh, we’d love some pictures of the two of us.”

MICK ROCK: Freddie connected with [fashion designer] Zandra Rhodes and that whole black-and-white theme. My brief for the cover of Queen II was exactly that: they wanted to feature the band and it was to be a black-and-white concept.

I’ve always been upfront about where I got the idea for the cover shot: Marlene Dietrich. It was unique. No other shot in my thousands of photographs was influenced in this way.

Freddie knew immediately that he wanted to be Marlene, and that we’d figure everything else out around that. We talked to the rest of the group and they were interested, but they also wanted a shot where they were all dressed in white against a white background.

BRIAN MAY: If you are looking for the answer to the question, “What was going on here?” I think there was a lot more than meets the eye.

By this time we had known Mick for a while, and I would venture as far as to say that Mick’s friendship with Roger was the one that cemented us together. They shared many interests and attitudes, plus an appetite for fun.

I think in these sessions you can see Mick interacting, very consciously and intelligently, with us all on different levels: a close personal relationship with Roger, who was probably the most fashion-conscious of us all; a good professional relationship with Freddie, along with a shared passion for graphic design; and with me a dialogue about the medium of photography itself, which has always been my second-biggest passion after music; John’s contribution was also, as always, important although he was perceived as The Quiet One. John would ask questions like: “But what is this going to look like in the records shops, on the racks?”. He had a way of grounding us, and probably stopped us taking ourselves too seriously, which was an important factor in our development, here and elsewhere.

My own primary fascination with this project was its duality: soundwise, the Queen II album was already totally and deliberately split down the middle. It had a Side White and a Side Black, both very different in character – so different in fact that it was almost like two Queen albums going in opposite directions; the two sides featured the songs White Queen and The March Of The Black Queen; we had evolved our stage costume designs to be pure black and white, again a duality. So it was important to me to develop the two concepts of photographs side by side: on the one hand the entirely ‘low-key’ image a la Marlene Dietrich, and on the other hand the entirely ‘high-key’ image of us dressed in white. Mick had the skill to convert these dreams into fine pieces of art.

THE MARCH OF THE BLACK QUEEN (LIVE AT THE RAINBOW)

A very similar set up was used for the opening part of the video for ‘Bo’ Rap’, which became such a milestone, both for us and, it turns out, for the history of video clips, all around the world in the summer of 1976. But the Queen cognoscenti know that these kind of images were first created for the Queen II album, some two years earlier.

MICK ROCK: Sheer Heart Attack was different from the Queen II cover because the band were much clearer about what they wanted. They came to me with a specific brief: “We want to look wasted and abandoned, like we’ve been marooned on a desert island.”

It was their concept. They brought their own clothes. I got in sprays, glycerine and Vaseline, and we greased them up and then spritzed them. Down on the floor they went, and I just shot until I was done.

FREDDIE MERCURY: God, the agony we went through to have these pictures taken, dear. Can you imagine trying to convince the others to cover themselves in Vaseline and then have a hose turned on them?

Everyone was expecting some sort of cover – a Queen III cover, really – but this is completely new. It’s not that we’re changing altogether; we’re still the same dandies we started out to be, we’re just showing people we’re not merely a load of old poofs, that we are capable of other things. [1974]

BRIAN MAY: Yes, it was agony this session. But it was worth it. I think we wanted to explode our own myth. We didn’t want to be pretty anymore.

MICK ROCK: There was plenty of bickering, disagreement and discussion, but that was part of the process. I never saw any ganging up or experienced any bad feeling. They bitched to each other’s faces. They were genuinely fond of each other. They were a group, and they wanted to make that super-clear.

KILLER QUEEN (Top Of The Pops)

This was published in Classic Rock issue 65

Roger Taylor is 65 on July 26

Read about the upcoming live Queen DVDs here