By the time Opeth released their 11th studio album, Pale Communion, in 2014, the Swedes had left their death metal roots long behind them. As mainman MIkael Åkerfeldt prepared to pick up an award at that year’s Golden Gods ceremony, he looked back on their unique career and revealed just why he tuned out metal’s gatekeepers.

It’s Saturday June 14 and One Direction are halfway through the encore of their second night headlining the 65k capacity Friends Arena in Solna, Sweden. Somewhere in the crowd, there is a 40-year-old man with shoulder-length hair looking slightly disconcerted, quietly resisting the urge to mouth along the words to Story Of My Life as his daughter bounces with excitement, in the way young girls do on such occasions. This is no ordinary man, however; he’s one of metal’s greatest visionaries and, in more recent times, perhaps one of its most vocal critics – though you could say the chances of him being recognised here are pretty slim.

“Well, I was in the minority there, being an old dude for one,” laughs Opeth mastermind Mikael Åkerfeldt. “It kinda felt like they’d just dragged up five guys from the crowd… if there were guys in the crowd! I couldn’t see the fascination, I felt a bit sad in a way. Story Of My Life is the good one so when they played that, I turned to my daughter and said, ‘This one’s OK.’”

As it transpires, metal isn’t the only genre the Opeth leader can see benefiting from a good kick up the arse.

Fast forward a couple of days and a sleepy-looking Mikael is backstage at the IndigO2 in Greenwich, enjoying his last cigarette as a mere mortal, while his two daughters play close by. In a few minutes, he’ll be walking out in front of 2,000 fans, peers and industry bigwigs to become a Golden God – the Golden God, to be precise – the highest accolade of our awards ceremony and, in our humble opinion, the entire metal world. He joins a list of legends that have helped shape everything we know about heavy music, including the likes of Kerry King, Joey DeMaio and some bloke called Lemmy. No biggie, then.

“It was hard to know what to expect, in a way,” says Mikael, sparking up another Marlboro Light after collecting his gong. “We were anticipating some of the metal magazines turning their backs on us, but so far that has not happened. I don’t really know what awards mean but people have been grabbing my shoulder, looking me in the eyes going, ‘This is a big deal!’ So I feel honoured, flattered… happy.”

Such an honour is reflective of an unusually organic, slow-but-steady upward trajectory that has brought them to where they stand today: one of the most passionately admired heavy metal bands in the world. The beginnings were incredibly humble indeed, with a 16-year-old Mikael joining on bass (“I liked the cool logo with the inverted cross”) and eventually taking the reins in search of more adventurous musical philosophies, driven by a burgeoning desire to cross-pollinate his love for death metal with the 70s British prog influences of Pink Floyd, Camel and King Crimson.

By the turn of the millennium, Mikael’s creative invincibility knew no bounds and the mesmerising technicality and soul of fifth album Blackwater Park raised the band’s profile, in the process encapsulating just how exciting metal had become in the hands of those who dared to think differently. A record deal with Roadrunner for 2005’s Ghost Reveries soon beckoned and after putting out one of the finest metal albums of its year in Watershed, a frustrated Mikael deleted his demos and was determined to start again, this time pushing his art to its very limits. The result was 2011’s Heritage, a departure from the death metal riffs and growls that the band made their name playing, in favour of more jazz-rock and fusion-inspired ideals. It was a move that angered a small yet vocal minority of fans into raising the question: are Opeth still a metal band or has Mikael gone too far?

“Even if it rubs people the wrong way, we are still a metal band,” he reasons defiantly in the face of less-than-favourable reactions to his band’s sonic evolution. “For me, metal is a progressive form of music. It’s not one thing, it’s a shitload of things. If people felt Heritage wasn’t metal, I would say the foundation for it very much was. I would not have written the album without the background I have. I’d like to think metal should be rebellious, even within its own genre. Maybe, in a way, what we are doing is rebelling against metal, but that’s only because we love it so much.”

It’s a bold statement, but also one that raises the question of how one begins to quantify what metal even is, with what barometer it should be gauged and how opinion – especially in the days of heightened public presence online – is purely subjective.

“People will always scrutinise what metal is, and it all comes down to definition. Me and Fredrik [Åkesson, Opeth guitarist] were invited to choose a few songs to play on a heavy metal radio station in Stockholm. We chose them in the studio and the DJ was like, ‘Judas Priest? Clean vocals. Not metal.’ And I was like, ‘What? You can’t play Judas Priest on a metal radio station?’ I was shocked. Not only that, but it was it pretty rich of them to invite us down to choose tracks and then jump in to decide what’s metal or not. That made me very upset. I’ve seen that attitude in a lot of people. I’m not stupid, I can hear people saying we’re not a really heavy metal band anymore. But I think there are bands which have a very metal sound and breakdowns… but there’s something missing that makes it not metal to me. For me, our attitude is metal.”

You get the feeling that whilst inadvertently setting a precedent for controversy by challenging metal’s boundaries, Mikael is someone that, at heart, is overprotective of the genre that he fell in love with many moons ago. This is a man who refuses to listen to music dumbed down to binary signals, sneaks in Napalm Death and Whitesnake covers to unsuspecting crowds, cried when Dio died and, ultimately, one of few who have earned the right to point out when metal needs to try harder.

“If I’m rubbing people the wrong way, speaking my mind about contemporary metal… a lot of people get the impression I think it’s all shit. Which is not entirely true,” he explains. “It’s hard for me to be impressed, ’cos I always find the references. And I often prefer the originals!”

Perhaps it’s this rebel spirit that has captivated the hearts of fans around the world, the swathing hordes of loyal admirers congregating to applaud a band that take risks with their artform rather than simply phoning it in and pandering to the wider masses. This year’s upcoming 11th full-length, Pale Communion, could have easily been an apology record, a crowd-pleasing return to more extreme roots, but the Swedish quintet have thrown yet another staggering curveball and disappeared even further down the rabbit hole, while in the process delivering one of the best records you will hear this year. From the ethereal wash of opener Eternal Rains Will Come through to the symphonic earthy blues of Faith In Others, this is an album that feels heavier and more cohesive than its predecessor with little indication of a band backtracking. If anything, the vintage prog influences feel almost sharpened by its panoptic use of instrumentation, particularly with the heightened emphasis on keyboard passages.

“We had a different kind of mindset in the early days,” offers Mikael. “But then I fell in love with the mellotron and gradually it started taking more and more space. Now we use the keyboard almost in the same way as Deep Purple or Uriah Heep, it’s an important part of our sound. And I’ve found new ways of writing music through that. It’s all about experimenting with this band or nothing. I want to continue; I think we’re onto something that at least I find interesting.”

In truth, Opeth have always had far more to offer the world than just metal in its most conventional sense. Even on face value, while most of his peers were embracing a more traditional denim and leather aesthetic, Mikael was the black sheep of Stockholm, walking around in velvet jackets and corduroy flares. And if the opening track on their recording debut – the 14-minute In Mist She Was Standing – was anything of a mission statement, it demonstrated fearless musicianship unafraid to embrace the unorthodox and venture beyond usual confines. At the time that may have been the 90s Swedish death metal wave, but now you can’t help but get the feeling that Opeth are competing with themselves, in a league all of their own.

“We were a bit of a slow-burner,” Mikael admits. “We’ve been around for a long time. I’d like to think we’ve never played it by the rules, never taken any shortcuts… and we definitely weren’t an overnight sensation! I don’t want us to be a predictable band. Of course, we wouldn’t go completely crazy in order not to be predictable. I still believe in the quality of songs and good music, but for us it’s important to push our own sound further.

“I think there are a lot of metal bands out there that don’t seem to like what they’re doing,” he continues. “There are many whose last five records sound just like the one before and a lot of bands don’t have the guts to experiment. Maybe they don’t want to experiment, but that seems odd to me. Why wouldn’t a band want to rejuvenate themselves so they don’t get tired? Nowadays, I think most of the bands sound similar to one another. Or maybe that’s just old age!”

2014 has been a busy year for Mikael Åkerfeldt. It started with the final songwriting sessions for Pale Communion, before setting up to record at the historic Rockfield Studios in South East Wales, then preparing for Opeth’s first show since September at the THC-fuelled utopia that is Roadburn Festival, which Mikael curated. Since then, it’s mainly been busy weekends performing on an array of festival stages around Europe – the calm before the storm, leading up to album release and the inevitable world tour. Which, for the time being, means he could be headlining a stage at Download one day and doing the school run in his Kiss shirt the next.

“It can be crazy juggling life like that,” opines the frontman. “I might be on a six- week tour with all the attention on us as a band, but then I’ll arrive at Arlanda Airport in Stockholm and within the hour be picking my kids up from school. I might be tired, but immediately I step into Dad mode. I’ll be pushing my kids on the swing wondering what happened!”

For Mikael, the responsibilities of parenthood are a welcome reality check from the stresses of the job and a humbling departure from performing to thousands of adoring fans across each continent. Naturally, he prefers to keep the two separate, in order to focus on being the best at both.

“I don’t go through books on how to be a good Dad or anything,” he asserts. “They’re not really aware of what I do, it’s more friends at school… they’ve come home and gone, ‘Daddy are we famous?’ And I’d say, ‘No.’ And then they’d ask, ‘Are we rich?’ And I’m like, ‘Fuck no!’ So my kids are not that impressed, at least not with me. They were more impressed with Chris Jericho [at the Golden Gods], even though they didn’t really know who he was!”

If you’re struggling to imagine what else Mikael gets up to in his spare time, it’s probably because he seldom discusses his life beyond music:

“I don’t do much, to be honest. I’m pretty easy going and don’t ever ‘kill time’. I play badminton… best case scenario is three times a week. I have an occasional beer and when I go out, it’s usually with the guys from the band. My record collecting takes up a lot of hours; I spend ages buying, listening to, even polishing records. Maintaining the database, ha ha ha!”

This collectormaniac, borderline obsessive streak is something that stems all the way back to Mikael’s early adult years. While working at an acoustic guitar shop in his native Stockholm – an experience which shaped his affection for more subtle and delicate sounds – Mikael was the kind of teenager that spent much of his spare time hoarding videogames, even when he didn’t have the time to play them.

“I’ve played a lot of videogames over the years. I bought more than I could play; I always had a stash of unplayed ones and soon enough I found myself not really bothering that much. Every now and then I still do. And that’s more like killing time, to be honest. It’s fun but I get bored. Ten or 15 years ago I could sit up all night playing, but not anymore.”

There was a story about you spending a whole night gaming with no clue that the building next door was on fire until the firemen came…

“It was my building actually, the floor underneath me,” Mikael recalls, with lingering disbelief. “A woman died in the fire, too. I’d been up all night playing Phantasmagoria on my PC at the time. The next day there was a knock on the door and it was the cops asking if I’d seen or heard anything strange. But I’d had my headphones on, so had no idea. They explained there had been a casualty and a woman had passed away in the fire below. I felt like a bit of a slacker, to be honest.”

‘Slacker’ is probably not a word anyone would associate with Mikael Åkerfeldt these days. In the rare moments Opeth have enjoyed some time off, he has worked on the Storm Corrosion side-project with longtime friend and Porcupine Tree mainman Steven Wilson, provided spoken words for Dream Theater, collaborated with the likes of Devin Townsend, Ihsahn, Soilwork and Genesis guitarist Steve Hackett, as well as fronting Bloodbath (which he eventually quit in 2012 due to his busy schedule) and singing on a handful of early Katatonia records. Everything from Opeth’s labyrinthine musical endeavours to Mikael’s bone-dry quips to the crowd have very much been works in progress, perfected with practice over the course of time.

“I’m not much of a fun guy, really,” he admits with a nervous laugh. “I have a sense of humour, I guess. It’s quite disarming actually, being a metal guy on stage and expected to do the whole, ‘YEAH? OH YEAH! THROW THE FUCKING HORNS, DUDES!’ thing. I could never do that with a straight face, not that I’m saying it’s bad or anything. When we started, I said nothing except ‘Thank you’, because I didn’t know what to do. I was shy. I still am shy.”

The turning point came when Opeth and Strapping Young Lad joined forces for 2005’s Sounds Of The Underground tour, a jaunt which helped the frontman muster the confidence needed to conduct himself naturally and be at ease on stage. “I’d be talking to Devin 10 minutes before he went on and he’d be cracking jokes. When he walked out, he’d be a bit distorted but it was still him. So I figured maybe that could work for me – not that I tried to rip him off – just go out there and be myself, and talk to the crowd like I would talk to my friends.”

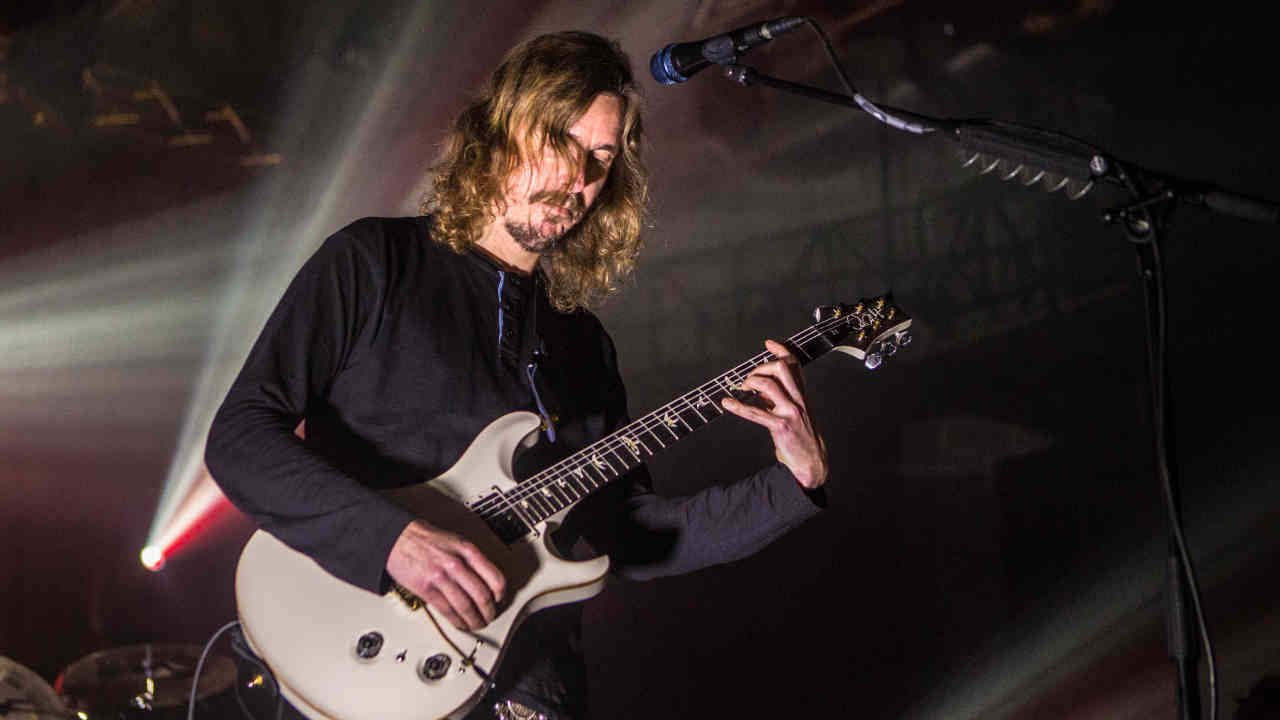

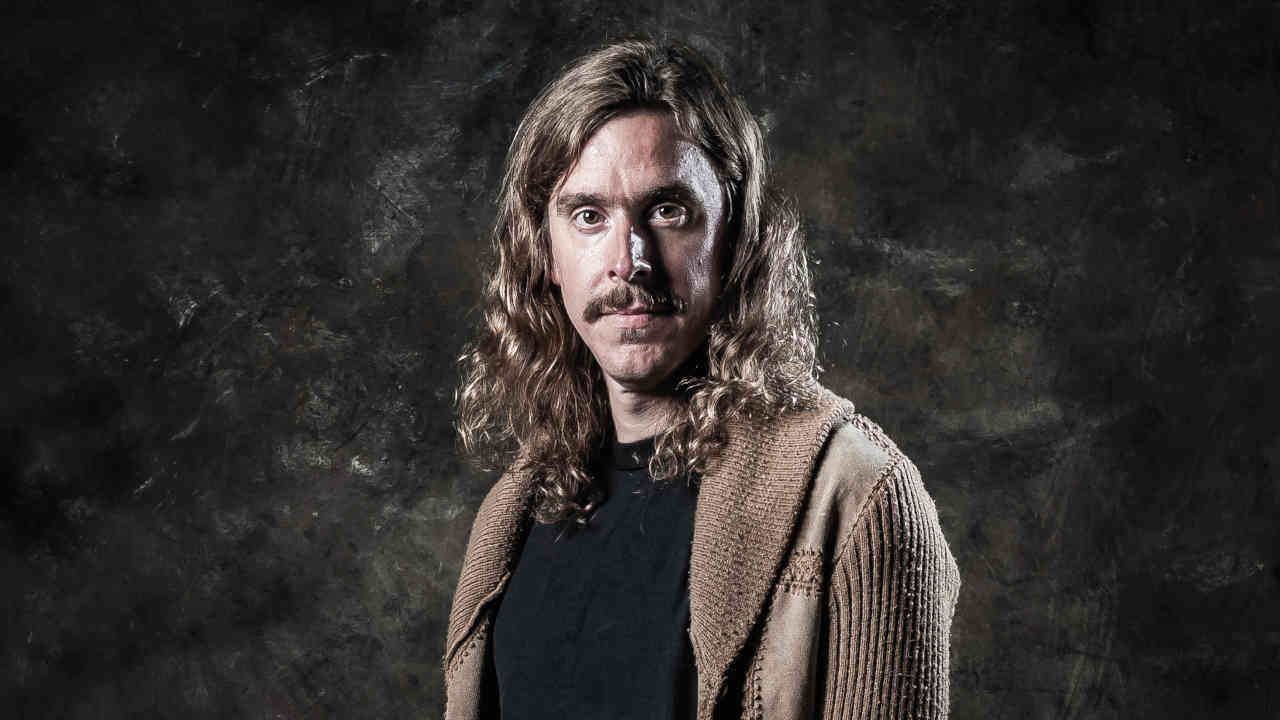

It doesn’t take long to figure out the humble, sarcastic yet charming man you see on stage is pretty much what Mikael is like all the time. He’s polite and articulate, sharp and witty – there’s a sense of honesty as he deadpans in a manner that fluctuates between self-deprecating and faux-cocky. He denies being any kind of scene hero (“I don’t see myself as a figurehead, I’m just a dude with a guitar”) or part of any particular movement. He’s the kind of man that hates looking tough for the camera, like that time we asked him to wave a sword around for the cover of Metal Hammer several years ago.

“Don’t remind me!” laughs Mikael. “When the swords were brought out, I was like, ‘Oh no!’ I was in jeans and a shirt, I didn’t look like a barbarian warrior. I was uncomfortable, especially when getting told to look mean. There was one photo where I tried, but it looked silly.”

As Opeth approach their 25th anniversary in 2015, it’s more than evident that the band are in a good place, quite possibly the best they have ever been. Mikael is the first to admit they were overwhelmed by the logistical nightmares and lineup changes that plagued the Deliverance and Ghost Reveries sessions just as the new millennium dawned, but those dark days remain firmly behind them. The Opeth leader is more than grateful for his band’s success, and still astonished by some of their achievements.

“When our manager Andy Farrow started taking care of us he said, [nasal Yorkshire accent] ‘Ten years from now, you’ll be playing the Albert Haaaall!’ I was like, ‘Yeah right, no way, impossible…’ but we did!”

How could we forget? You said the word ‘cunt’ in the UK’s poshest venue.

“I did, just because… it’s Opeth, you know? We were the first screaming band that played there, ha ha ha! When I was a kid, I used to saw toy guitars out of the desk in my room so I could mime in front of the mirror with posters of Kiss and Maiden on the wall. My dad wasn’t happy! But that was basically my dream. And now – not to say I’m in that fucking league – I’m doing it.”

Originally published in Metal Hammer issue 260