With modern progressive giants Opeth celebrating their 25th anniversary this year, we thought there was no better way to celebrate than to join them on the journey to their very first live performance with a full-blown orchestra, and to get the inside story on all things Opeth, from their turbulent history to a bright future…

Briskly ushered out into the blackened night, carrying what seems like an endless procession of heavy equipment and instrument cases, the motley crew of darkly dressed characters with whom we are about to share a three-day adventure gather into a pack of first-time greetings and friendly embraces.

Prog’s most intimate journalistic journey with Opeth yet begins in a humid Bulgarian car park amid a scattering of empty airport trolleys and road dirt. And before we know it, keyboard player and latest Opeth recruit Joakim Svalberg snakes a conspiratorial arm around our shoulder and asks with a wry smile: “Do you like beer?” And we’re off…

It’s been 25 years since frontman Mikael Åkerfeldt joined Opeth and turned them into the musical marvel they are today – a convention-breaking collaboration of ideas, based on a profound passion for music and proficient musicianship, as testified through the band’s impressive 11 prog metal albums.

Åkerfeldt admits: “When you say it’s been 25 years, it makes it sound old and veteran-like, but physically I don’t feel old, and as a band we collectively do not feel old. Right now we are not rehashing anything and we don’t feel nostalgic. We are not trying to recapture the spirit of the old days but if I look back and think of what we did 25 years ago when I was only 16, then yes, I guess it feels like a long time.”

Prog gets packed into an airtight van amid the band, crew, concert gear and tour manager, where beers are cheered and heads nod appreciatively to Sad Wings Of Destiny by Judas Priest, which is playing on the portable stereo. Conversely, this album is somewhat linked to Opeth, as it was recorded in Rockfield Studios in Wales. Forty years on, this was the same place Opeth recorded their most recent album, 2014’s Pale Communion. “The crew do everything with the band,” adds charming guitarist Fredrik Åkesson as the Bulgarian countryside rolls by. “We are like a family and we want you to feel included.”

Cusp Of Eternity, taken from Opeth’s latest album Pale Communion.

Between laughter and cigarette breaks, there’s a sense of excitement all around as no one knows what is to come of this exotic voyage. For the first time in the band’s career, they will be playing a concert with a full orchestra, the Plovdiv Philharmonic, and a choir, in a dramatic venue: the Ancient Theater, Plovdiv.

It’s an exciting time for the band, but much like the bumpy road to our hotel through Balkan no-man’s land, Opeth’s path was not always a smooth one. The latest line-up could easily be described as their most stable yet. After a tumultuous start and multiple member changes, Åkerfeldt has found the most musical stability since he first joined the band in 1990.

“I think other bands in Sweden at the time thought we were shit because of the first Opeth singer David Isberg’s reputation,” Åkerfeldt remembers of the early days. “Although we hadn’t done that many shows, the ones that we did were not a success at all…”

Åkerfeldt met Isberg at the heart of the emerging death metal scene in Sweden when he was a young teenager. “David was the boss, even though he was a year younger than me,” says Åkerfeldt. “We first met through skateboarding and because we went to the same school. I was into Scorpions and he was into heavier stuff like punk, hardcore and grindcore. Those were terms I had never even heard of until I met him, so I guess it’s thanks to him that I discovered heavier music.”

“David Isberg said: “I’ve fired everyone – what do you say you and me are Opeth from now on?”

“He always used to call me a poser because of the fact I didn’t listen to music that was heavy enough for his taste,” Åkerfeldt admits. “Even though we didn’t really get on, he did make me discover different music and I would absorb everything he showed me like a sponge.”

Åkerfeldt’s first interaction with the band Opeth, meanwhile, started off awkwardly. “David was having issues with his band and then he said that he was going to fire the bass player,” explains Åkerfeldt. “David could do this because he was the boss, like a kind of Jon Bon Jovi or something! So he told me to show up at the rehearsal where he was going to fire this bass player and I would replace him.

“I didn’t really want to play bass, but I really liked the band’s logo and the devil imagery so I thought, ‘Why not?’ When I got there, everyone was looking at me like, ‘Who the hell is that guy?’ The whole band started to have a massive argument, which basically resulted in David firing everyone in the band! I was still waiting outside while all of this was happening and when he finally came out, he said, ‘I’ve fired everyone – what do you say you and me are Opeth from now on?’ So luckily I never had to play bass and went straight to guitar!“

“The two of us were writing songs and looking for other musicians, but he had a bad reputation so I was the one bringing in musicians, including my bandmates from Eruption [Åkerfeldt’s first group, a five-piece death metal band]. This was going to be Opeth version 2.0.

“We started getting shows and about a year later we went on a ski trip in Zell Am See, but I don’t remember doing any skiing because the trip was more about drinking Stroh Rum, which is 90 per cent alcohol. What I do remember, however, is that David left the band while we were on the bus back home.

“I wasn’t that displeased to be honest, because at that time we already started having a recognisable Opeth sound and I felt although his screams were good, his rhythm was bad and he did not fit in. This was when I became the singer of Opeth.”

S o began the band’s journey in developing their unique sound, starting with 1995’s Orchid. Åkerfeldt is adamant that Opeth’s emergence from the genre stemmed from his wide interest in different kinds of music.

“I didn’t even know that prog existed up until I heard Yes for the first time and I thought to myself that the album must only be an EP or something because it only had three songs,” he says. “They were long tracks, with a beautiful dynamic and lots of acoustic parts, which I have always loved. From then on, I was really intrigued by the dynamics of symphonic rock and progressive music. I also loved the switch between styles. Some parts sounded a bit jazz; other bits were harder and had extracts of Renaissance music.

“I was always less impressed with the instrumental side of heavy stuff and more into the rawness of the music because I honestly didn’t think those guys really knew how to play their instruments. For some reason, I always liked the screaming bits though, because they made me realise I could be a singer, even though I couldn’t sing!”

In Mist She Was Standing, taken from Opeth’s debut album Orchid.

“The first time we received any recognition was not until we released our first album with producer Dan Swanö,” he continues, “who was blown away when we started playing. After we had just finished recording Orchid, a famous death metal band called Unanimated, of which drummer Peter Stjärnvind is a friend of mine, came into the studio after us. They laughed when Dan told them that Opeth had a record, but then when they heard it, they were in shock. In fact, he told me later that they had to have a band meeting afterwards to discuss what they had just heard!” he chuckles.

“There were no demos in those days, so the first thing you recorded was your first album and at the time there were no bands that sounded like us. We had long songs, no blast beats, lots of acoustic arrangements, clean vocals and harmonies.

“Despite the fact we had long songs, we didn’t have anything that made us stick out because we didn’t really have an identity yet. Along came Dream Theater, which was a new and modern band that sounded like what I wanted to do, but we were nowhere near that field of music because we were a death metal band. This is when things started to materialise for our band.”

After the success of 2001’s Blackwater Park, their first album produced by Steven Wilson, Opeth embarked on a world tour in 2001. This period marked a crucial turning point for the band, in which their new-found success allowed Åkerfeldt to push the experimental boundaries even further by releasing two albums at the same time, one soft and one heavy. The titles given to both 2002’s Deliverance and 2003’s Damnation offered more than clever imagery as the recording experience proved to be the most challenging Opeth had ever endured, despite the triumphant acclaim the albums received upon release.

“Opeth’s creative side has always been good and interesting, but other things have sometimes made the band difficult,” Åkerfeldt reminisces. “Deliverance and Damnation were difficult to record because of internal band shit. Without saying too much, there were things coming into the band that did not belong there…”

Åkerfeldt is alluding to the anxiety attacks that plagued him at the time, and of the substance abuse issues that would eventually see the departure of drummer Martin Lopez, who went on to form Soen. One wagers at the time that the band never expected they would be selling out the Royal Albert Hall 10 years later.

As Eurythmics plays on the kitchen radio in the background, a euphoric medley of red wine, whiskey and outlandish local dishes lie before us in the hotel restaurant in the early hours, fuelling the friendly and easy-going atmosphere among the band members. It’s clear that Opeth’s stellar reputation as a respectful, intelligent and approachable band is true. The deadpan Swedish sense of humour is evident and the conversation always revolves around music.

Today, they seem truly content. “I feel that the recording process for the band has been the most fun it has ever been with this current line-up and during the making of the last album, Pale Communion,” says Åkerfeldt. “It was really fun, and I realised that I had never had fun recording before that album. I always enjoyed working hard and seeing the music through tunnel vision, but it was never fun and I was dispensing an insane amount of energy.

As the sun rises high above the amphitheatre in Plovdiv, Bulgaria’s second largest city, Opeth are mid-rehearsal for the sold-out show they’ll be playing in front of 4,000 fans. The calmness surrounding the band in the empty historic monument echoes the serene and psychedelic feel of Pink Floyd’s 1972 film Live At Pompeii.

Opeth’s live shows are one of the most impressive aspects of the band, as Åkerfeldt interacts with the crowd and proves his charm as a frontman. The intricate nature of Opeth’s sound, combined with the simplicity of the vocals, fill the auditorium with enough emotion to make even the hardest of metalheads swoon.

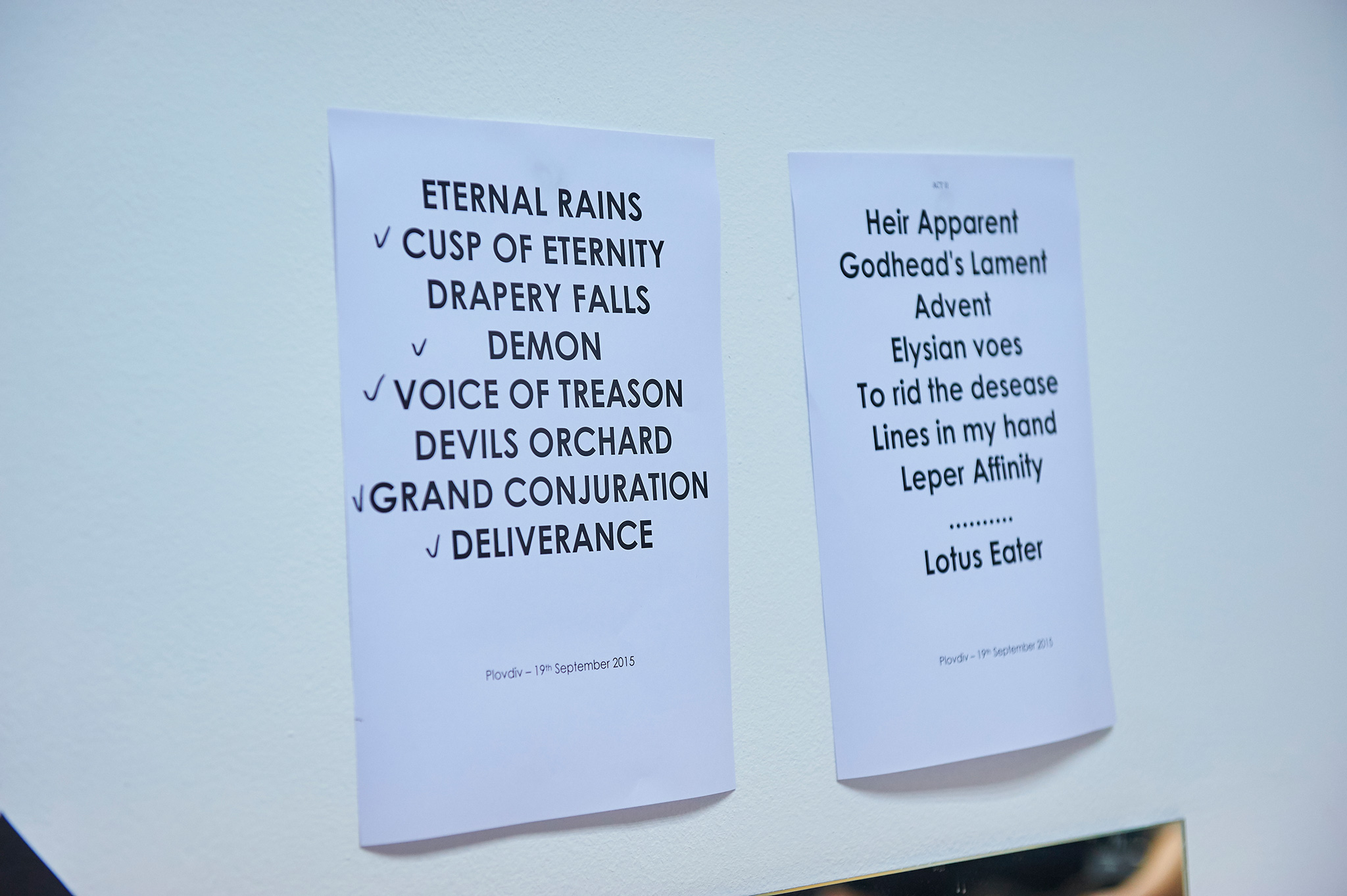

The setlist for this show has been carefully selected to represent the band’s full discography, featuring hits like* The Grand Conjuration*, The Devil’s Orchard, Demon Of The Fall and Cusp Of Eternity. Having heard these songs being played on a loop during rehearsals to achieve a perfect correlation between band and orchestra for the past two days results in an extraordinary live music experience.

The charismatic singer says: “The glitches that make a show bad, as opposed to good, are so tiny that it’s usually only us that hear them. Generally we’re a pretty consistent band when we play gigs so it’s never a complete train wreck the whole way through. I absolutely love it when there’s a total disaster and the live music is totally fucked. No one notices, but we’re all looking at each other wondering what the hell we’re doing. I love those moments because you have to find a way out of them and come back together, then once you do, it’s like, ‘High five, guys!’

“On a scale of one to five, I would say that we’re usually a three, and when it’s a five, the whole band has to agree that it’s a five. Out of 100 shows, that probably happens only once or twice.”

As the audience give Opeth a standing ovation, the band crawl off the stage, exhausted. Åkerfeldt sits hidden behind a stone wall, drained but still feeling the after-effects of the show’s adrenaline. He’s clutching an envelope in his hand, a gift from a fan, which he opens. “He forgot to put my cheque in here,” he laughs.

This incredible event marking 25 years of Opeth serves as the greatest assurance that the band are still making relevant, innovative and exciting music, while selling out concert halls and amphitheatres across the world. They remain one of the most captivating and successful prog bands in the modern music age.

Ultimately, Åkerfeldt explains what success means to him. “Our last album didn’t sell as well as the one before, and of course you always care about selling albums and tickets to shows, but I don’t care about any other kind of success. For me, we are truly successful when the five of us are able to write music that is relevant and that is good, as well as playing good shows. Doing a killer show means almost everything to us and we wouldn’t have a career if nobody had listened to Opeth.

“At the end of the day, it’s about the dynamics between the five of us, how we play live and what our records sound like – not album sales.”

For more information, see www.opeth.com.