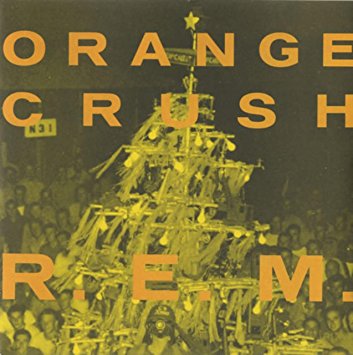

It’s Thursday so it must be Top Of The Pops. On the show this week, June 15, 1989 is a four-piece band from Athens, Georgia whose time seems finally to have come. REM are here to perform Orange Crush, the first UK Top 40 hit of their career thus far.

The song snaps into action with a quasi-military drum figure and guitar arpeggios. Shirtless in a grey suit and shades, the singer shimmies about with a large bullhorn. The tune itself is a sharp confection of pop weirdness and stomping rock. At the end, presenter Simon Parkin gushes into the mic: “Orange Crush – particularly nice on a hot day!”

Parkin wasn’t the only one to entirely miss the message.

“Like most of our stuff it’s definitely an anti-war song, but it’s a subtle one,” explains REM bassist Mike Mills. “There was no real sign that it was a big protest song, so most people listened to it and didn’t realise. It’s most directly related to the indiscriminate use of Agent Orange in the deforestation of Vietnam and the horrible effect it had on everyone, from soldiers to civilians. It was just a terrible poison that was so widely used it caused a lot of pain and misery. Yes, there was some irony in the sweet deliciousness of the pop drink versus the horrible effects of this chemical. The ironic juxtaposition of those two terms was no accident.”

Orange Crush had been in REM’s live set-list for a year before fetching up on sixth album Green, released in November ’88. It was a pointed commentary on US involvement in Vietnam, albeit sugared in the fizz of a four-minute power-pop song.

It’s the tale of a young American football prodigy leaving home comforts for south-east Asia. Singer Michael Stipe’s father had served in the helicopter corps there, which gave his lyrical concerns a more personal edge. There are references to goggles and whirlybirds overhead, though the tune’s main hook – ‘Follow me, don’t follow me/I’ve got my spine, I’ve got my orange crush’ – addresses a more overtly sinister form of warfare.

Agent Orange was used to devastating effect during the Vietnam war. An appallingly toxic mix of herbicides and defoliants, nearly 20 million gallons of the stuff he US was sprayed over forested areas by the US military over a nine-year period up to 1971. The idea was to root out guerrillas from rural communities and force people into American-controlled urban cities. Of the three million Vietnamese thought to have been affected by Agent Orange, it’s estimated that 400,000 were killed or maimed and it caused 500,000 children to be born with severe defects. Veterans on both sides of the conflict, meanwhile, have shown increased rates of cancer and nerve disorders. Returning US soldiers were also subject to accelerated instances of their wives having miscarriages or infants born with abnormalities.

“The soldiers themselves were helpless before the decision by the government and the military to use this stuff,” laments Mills. “They had no say in the matter at all, yet they were the ones who were forced to suffer the consequences.

“Orange Crush was a great example of Michael’s genius as a lyric writer. As he became more assured, he had definite ideas about what the songs were about. That didn’t mean you had to necessarily figure it out, you could just listen for pure enjoyment. But if you wanted to dig a little deeper there was always something there. That’s always been the case with my favourite songs.”

Orange Crush was a collision of old and new REM. Since forming in 1980, their defining tropes had been the jangling rush of Peter Buck’s artful guitar, the wordless moan of their Mills-led harmonies, drummer Bill Berry’s deft rhythms and the delicious pull of Stipe’s cryptic vocals. Orange Crush had all these things, plus a killer punch and added sparkle.

REM’s tenure with Miles Copeland’s IRS label had come to an end with 1987’s Document, which had gone platinum in the US. With the majors circling, the band opted for a long-term deal with Warner Bros. Buck justified their decision by citing the company’s support of left-field artists like Randy Newman and Van Dyke Parks.

“One of the main reasons we signed with Warners was because we had creative control over everything we did,” Mills says. “REM always have done whatever we felt was right. So the only decision makers were those of us in the band.”

They countered accusations of selling out to a major by using their commercial clout to spread their anti-Republican politics.

“As we sometimes did with our album titles, Green meant a lot of things at that point,” Mills recalls. “It was certainly about ecology and the environment. The record was released on Election Day in 1988 [Bush v Dukakis] and we were very involved in that election. As you become more popular, you’re very aware of having an effect on more and more people. So for Michael as a lyricist, and all of us as political activists, you’re able to have a forum for what you think and feel. Plus we were getting grief from people about signing to Warner Bros, so there’s a little irony in the title too. It exists on a level of serious intent and also as a bit of a laugh.”

The resulting tour saw them fill arenas the world over, marking the birth of REM the stadium monsters of the 90s.

“It became a real live favourite,” Mills says of Orange Crush. “On the Green tour I’m pretty sure we played it every night. Then whenever I made the set-list on subsequent tours I always made sure Orange Crush was in there. It’s one of my very favourite songs to this day.”

This article originally appeared in Classic Rock issue 185.