According to prog’s conventional history, the genre began as essentially a British phenomenon with a few American travellers. However, given its roots in the psychedelic revolution of the mid-late 60s, it should be no surprise that musicians outside rock’s English-speaking heartlands ended up applying adventurous creative twists to their hippieish visions.

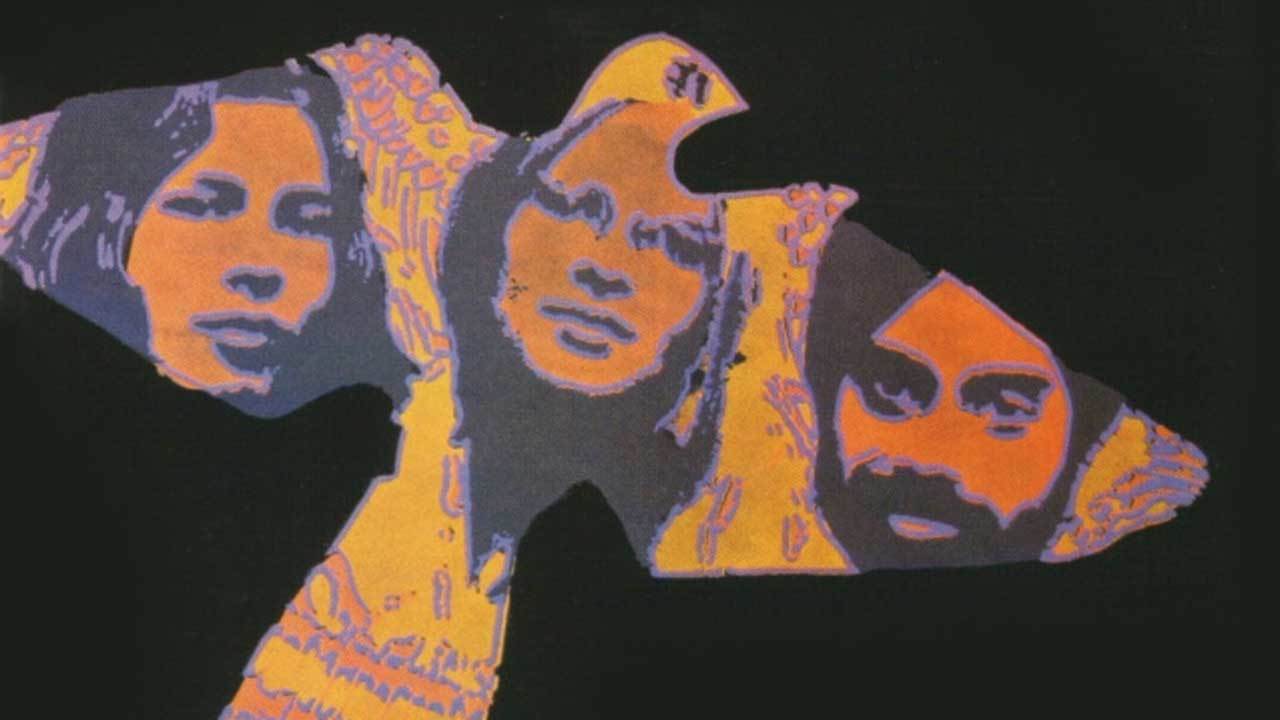

In 1968, teenage students Nina Johansen and Rune Walle began writing starry-eyed folk songs together in the Norwegian coastal town of Manger, but they weren’t content with sticking to the Incredible String Band-style mellow fruitfulness that an acoustic guitar and voice could produce. Instead they hooked up with what must have seemed a highly exotic figure in what was a decidedly white, mono-cultural Scandinavia – a Sikh student from New Delhi named Satnam Singh. Walle was already a keen sitar player, inspired by The Beatles-endorsed Ravi Shankar, and Singh’s expertise on flute and tabla helped them create a beguiling and unique sound. They called themselves Oriental Sunshine, and the resulting music, even at its most basic, evoked reveries of hippie travellers pitching up in a sun-dappled Indian valley and jamming with some local troubadours.

The reality was more likely the reverse, given Shankar’s fish-out-of-water status in a country that had barely any Asian residents. An unlikely triumph on a TV talent show suggested that his cultural influence was more than welcome, and the trio made a more lasting mark with their 1970 debut album, Dedicated To The Bird We Love. Released on the Philips label, the assistance of prominent Norwegian jazz musician and producer Jan Erik Kongshaug helped enhance it from a twee curio into something far more elegant and evocative. A trio of fellow jazzers added subtle non-linear arrangements, allied to the central trio’s slightly wonky, wispy, mantra-tinged brand of folk song, Johansen’s breathily wistful pipes and a freewheeling sitar. It all made for a distinctly proggy listen. If prog was the logical progression for those who wanted to break free from the straitjacket of generic rock, this album feels more like musicians set free. Although the core trio sometimes sound like they’re not quite sure what to do with that freedom (Walle’s sitar sounds particularly untutored), that only adds to the charm of Dedicated…

You get the feeling they might have gone on to expand on this vision further still, but after Johansen’s father died during the making of the record, she felt unable to continue, so this remains Oriental Sunshine’s sole earthly testament. But as one-offs go, it’s really quite something.