Formed in 2001, The Mars Volta boldly took rock music where no band had gone before. Four years later, as they released their second album Frances The Mute, Classic Rock sat down with mainmen Omar Rodriguez-Lopez and Cedric Bixler-Zavala and uncovered the secret history – including death, drugs and Drive-Ins – of these enigmatic mavericks.

With hindsight, it was obvious something was wrong. It was a night in February 2001, and the Astoria in London was sold out. Famous faces flitted through the audience: Bush frontman Gavin Rossdale smiling a millionaire’s smile, Kate Moss gliding barely noticed through the VIP area. The air was charged with a sense of occasion; a sense that if there was a place to be in London that night, it was here.

The source of the excitement was At The Drive-In, a young band from Texas who were reaching critical mass and about to go stratospheric. Their brutal cocktail of hardcore punk and angry metal had the music press in a lather and their album Relationship Of Command was earning them a rabid following worldwide. They looked amazing, too – that none-more-black muso chic that so many bands aim for and fall short of, that they wore with ease. Then there were the Afros; most of them had a feral shock of hair topping their diminutive, rock-god frames.

But amid the on-stage histrionics, all was not well. There was an awkward vibe up there. Singer Cedric Bixler-Zavala, a punked-up ball of energy, shrieked the rap-like vocals on One Armed Scissors and Invalid Litter Department. At one point he ran across the stage, leapt onto the drum riser and sprung off again with a reverse scissor kick. Then he shouted venomously at drummer Tony Hajjar, who returned fire. Later he turned on the audience to vent his spleen about something, but their oblivious roar and the acoustics of the room drowned him out.

Guitarist Jim Ward ranted like a petulant prefect at the moshpit, which frothed with limbs. Lead guitarist and musical lynchpin Omar Rodriguez-Lopez averted his gaze, turned back to his amp, fiddled with the settings and shook his head, defeated.

By the time they trooped offstage and the audience went ballistic, At The Drive-In seemed almost disconsolate. The air of being The Next Big Thing hung over them like a hex. The band split just weeks later. Some of the ex-members formed emo band Sparta.

Cedric and Omar are now two albums into their band The Mars Volta – an entirely different prospect altogether. Their 2002 debut EP Tremulant had pundits scrabbling for names such as Yes, King Crimson and Pink Floyd in a desperate attempt to categorise The Mars Volta’s singular sound. But such comparisons give a false idea of what The Mars Volta are achieving. Far from peddling ersatz prog, they are, in the genuine sense, a modern progressive rock band.

With a real-life tragedy humming at its core, their second album, Frances The Mute, is a bold and impressive musical statement. If there were a concept album check-list, it would tick all the boxes: it weighs in at 77 minutes is comprised of just five songs (a ‘five-song cycle’, if you will); two of the tracks (Cygnus… Vismund Cygnus and the centrepiece Miranda That Ghost Just Isn’t Holy Anymore) are almost a quarter of an hour-long apiece.

There’s a central conceit behind the lyrics and a continuous theme running throughout the music. By turns languid and frantic, the album succeeds in adhering to both a punk aesthetic and the more holistic approach of ‘album rock’. It’s a demanding listen.

“We don’t want to be background music,” Omar says. “We want it to be like a film, like the stuff we like: you turn it on, you shut up, and listen from beginning to end.”

Born in Puerto Rico, Cedric Bixler-Zavala and Omar Rodriguez-Lopez met when their parents relocated to El Paso, Texas. By the late 80s, while their friends were into Jane’s Addiction, Red Hot Chilli Peppers and Happy Mondays, they were skipping class in high school to rehearse in bands. They drew inspiration from the old-fashioned punk of The Germs, Black Flag and Circle Jerks, as well as the experimental sounds of Gong and Soft Machine. Their own ethnic identity also fed into the mix.

“What set us apart was our musical imagination,” Omar says, “and that comes partly from us being Hispanic kids growing up in the States. Traditional music is the centre of Hispanic culture, and as a kid I was into salsa and I was also into punk rock. True inspiration comes from the bastardisation of all this, of finding your place and just inventing things yourself to stay happy.”

Omar and Cedric’s obsession with music first bore fruit with the five-piece hardcore rock band At The Drive-In in 1994. With their raw talent and a strong work ethic, word of mouth spread their name fast. Their third album, Relationship Of Command, produced by nu-metal svengali Ross Robinson, was released on the hip Beastie Boys’ label Grand Royal, and both press and public stood up and took notice.

“We’d been together for six years before the media hooked on to us,” Omar says, “and by then all the usual tensions had come up in the band and been recycled. Relationship Of Command was seen from the outside as this big record, but to us it was a very small record. We were retreading ground from our second album, In/Casino/Out.”

Listening to Relationship Of Command now, with its esoteric song titles like Rolodex Propaganda and Arcarsenal, it’s a precocious, accomplished and somewhat brash alternative rock record, with Robinson having smoothed its rough edges. But the cross-pollination of musical styles that Omar refers to – the punk/salsa link so prominent in their musical DNA – is all but absent.

“By the time it came out, we were pulling in different directions,” Omar explains. “It was split between the three of them and the two of us. Cedric and I wanted to incorporate those different rhythms, different languages and concepts.”

“But instead of just doing it,” Cedric, adds, “we always had to have a meeting about doing it. It’s the difference between being with a girl who just gets you right away and one who overanalyses everything. When you have to say your intent out loud so many times, you end up feeling stupid.”

At The Drive-In came to a stop as the band toured the album through Europe in early 2001. Three weeks after that portentous gig at London’s Astoria, they found themselves playing The Vera in the Dutch city of Groningen.

“The Vera’s still one of our favourite places to play,” Cedric says. “It has such a history, and it’s an honour to play there. But that night we were playing like a bunch of sheep, like robots. It was the first time I turned to Omar and saw he was just catatonic. Everyone could see that. Even the audience noticed it. We needed a break.”

Citing nervous exhaustion, they nixed the rest of the tour and returned home to El Paso, intending to put At The Drive-In on hiatus for six months and then return to it refreshed. Cedric and Omar went straight back out on the road with their ‘mistress’ band, De Facto, a side project they had started up with their close childhood friend Jeremy Ward, playing a mellow, guitar-free fusion of Latin music and dub. But with pressure from the label, management and other members At The Drive-In to cut short the sabbatical and resume touring, Omar and Cedric quit that band.

Fuelled by the excitement of realising their musical vision unhindered Cedric and Omar moved to California’s Long Beach and put together The Mars Volta. Their friend and De Facto sound effects man Jeremy Ward was in, and they sought other like-minded musicians. “We came up against a lot of that LA mentality,” Cedric recalls. “Guys who could play but were more interested in the photo shoot, the interview, the money.

“But by the time we were preparing to record the first album we were bankrupt. The other At The Drive-In guys formed Sparta, got signed and got an advance straight away. We were rehearsing at home.”

The Mars Volta’s 2003 full-length debut album Deloused At The Comatorium (co-produced by Rick Rubin) was recorded over three months in the abandoned mansion in Laurel Canyon where the Red Hot Chilli Peppers made Blood Sugar Sex Magic 12 years previously. Chilis bassist Flea even played on the sessions.

Inspired by the suicide of artist Julio Venegas, the story of Deloused… unfolded inside the mind of its protagonist as he lay in a self-inflicted coma. Its multi-lingual narrative contained its own synthetic language. The band even wrote an illustrated book to accompany the story. The music’s dense, challenging blend of punk, psychedelic metal and Latin grooves indicated the daring but commercially dubious direction the band were taking.

The Mars Volta’s first concert was at an Anaheim club called Chain Reaction, a venue more in line with the Warp Records crowd and not a place At The Drive-In would have called home. They went on stage unannounced, did their thing, and remember the audience reacting – to steal a line from Bill Hicks – like a dog that’s just been shown a card trick.

But initial audience bemusement gradually changed to acceptance as the band supported the Chilli Peppers on their European tour.

“We were having a great time with the Chilli Peppers,” Omar enthuses. “We get along so well with those guys. Our band’s chemistry was really coming together. Halfway through the tour we found our current bass player, Juan Alderete, and everything started shining and this whole new world opened up to us and we were off drugs. And then Jeremy died.”

In March 2003, one month before the album was due to be released, Jeremy Ward, their buddy, the sound effects whiz who played off stage out of the limelight, was found dead in his LA home following a suspected drugs overdose.

“You’ve gotta understand,” Omar says, “when we talk about our childhood and all these things we’ve been through, there is a piece of the picture missing.”

With this he gestures, almost subconsciously, to the empty space between himself and Cedric. “Jeremy had rough copies of the record,” Cedric says, “but he didn’t get to see the record come out and hold it in his hands like we did, and he didn’t see the book come out. But he’s inside the grooves of our records; he’s inside the circuitry of our amps; he runs through our veins. His influence and spirit will always be there.”

Ward’s spirit certainly has had an influence on the shape of The Mars Volta’s second album, Frances The Mute, which takes its story from one of his most valued possessions. He had worked as a repo man, repossessing the cars of LA’s recalcitrant debtors. He thrived on the danger of the job – a bullet-proof vest was standard issue – and would come home with all sorts of treasures found in glove compartments and back seats: pictures of naked people partying, knives, drugs. Then one day he found a diary. It was the journal of a young adoptee, who had written in harrowing detail how desperate he was to find his natural parents. Ward brought the book to his bandmates.

“If you’re born with a broken heart, then you’ll spend the rest of your life trying to mend it,” Cedric offers. “If you look at a picture of Jeremy when he was 10 and then 27, he has the exact same look in his eyes. A haunted look. He related to the diarist’s loneliness, his disconnectedness.”

Frances The Mute sees them progress further down their own discrete path. It is an ambitious, self-produced work, rich in ideas and with a sweeping, cinematic scope. (Their love of film is pervasive: even their band name is a reference to Italian director Federico Fellini).

Within the five-song framework there are echoes of 70s prog, from the long guitar solos to the analogue tape effects and washes of ambient sound connecting the tracks. The lyrics are highly wrought, if quasi-intellectual, and some of them are in Spanish.

L’Via L’Viaquez revolves around 70s hard funk and dark, authentic salsa. Cassandra Gemini even breaks down into free jazz. Cedric’s dynamic vocal delivery is a whisper one moment, a scream the next. While there are elements of Can, Gong, occasionally even The Mahavishnu Orchestra, it sounds fresh, light on tricksy rhythm changes and awkward modulations, and spiked with the spirit of punk. Easy listening it ain’t, but it is an album you can really sink your teeth into.

“You should always challenge yourself as a musician,” Cedric says. “I don’t read reviews, don’t pay any attention to what goes around the music itself. Everything is secondary to the band, even the audience. When we play, the band is the audience. Sometimes it doesn’t connect, there’s no magic spark, and, well, you noodle. But when it does connect it's fun.”

It sounds arrogant, and maybe it is. But their audience, swelling in size with the anticipation of new material, seems to understand. A world tour beckons, and once again Cedric and Omar find themselves in a hot-ticket band, but this time it’s on their terms.

“There’s definitely room for people to be disappointed,” Omar laughs, “because we’re completely selfish and we’re completely on our trip, and if the next album is purely instrumental and Cedric just wants to play keyboards, then that’s what were gonna do. None of the attention paid to us or the success of our records is going to stop us getting where we belong.”

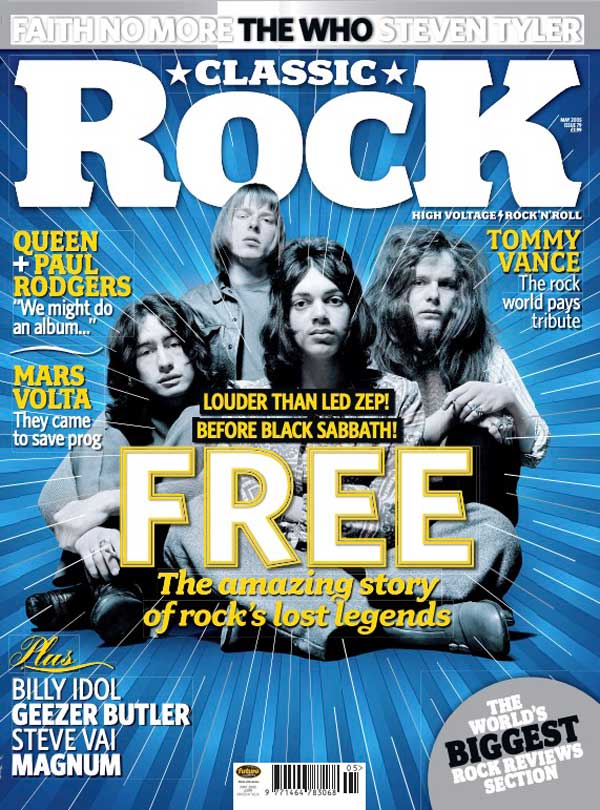

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 79 (May 2005)